Detail of the plate illustrated in fig. 6.

King William Courthouse, King William County, Virginia, ca. 1725–1726. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) The building, which faces south, is a one-story structure of red-colored brick laid in Flemish bond. The courthouse is the oldest courthouse still in use in the United States.

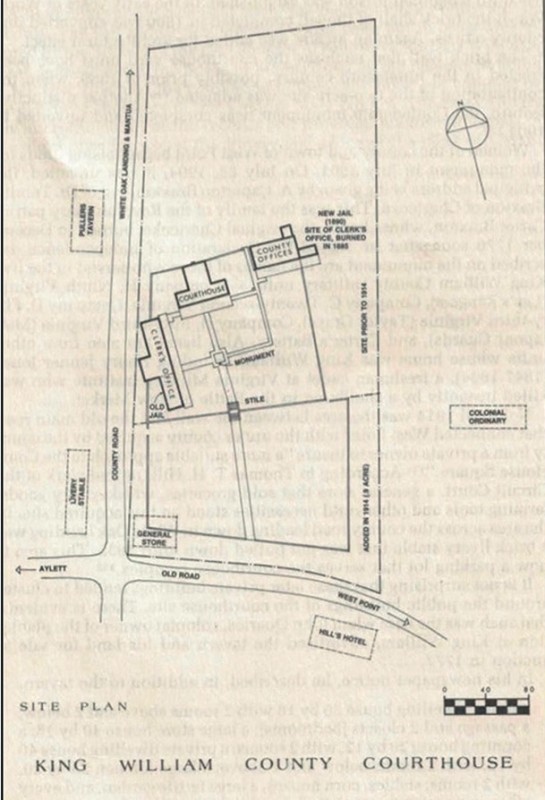

A plan of the King William County Courthouse property showing the conjectural locations of historic buildings, including the eighteenthcentury “Colonial Ordinary” to the east. The plan was made by the architect Graham Evans and is published in Alonzo Thomas Dill, King William County Courthouse: A Memorial to Virginia Self-Government (King William, Va.: King William County Board of Supervisors, 1984), p. 10.

Wetherburn’s Tavern, Williamsburg, 2022. (Photo, Robert Hunter.) Now a Colonial Williamsburg exhibition building, this tavern was built ca. 1742 and operated throughout most of the eighteenth century.

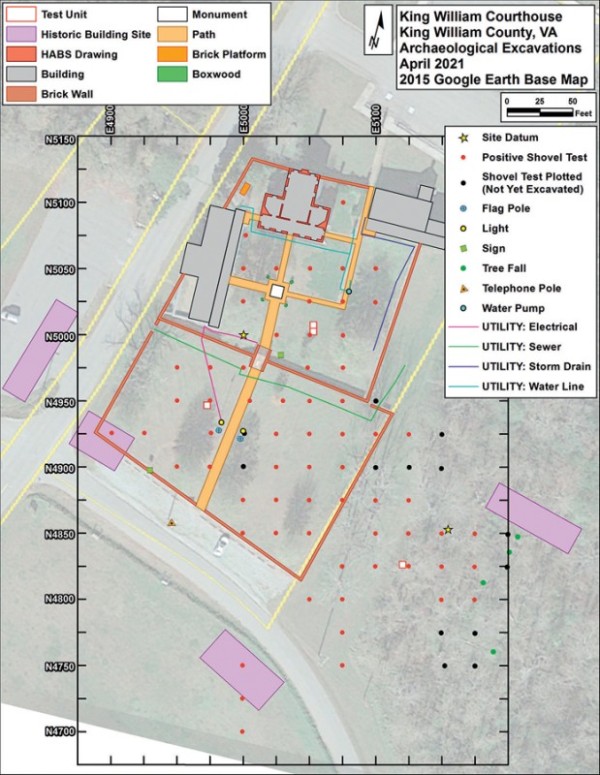

Plan of the King William Courthouse Archaeological Excavations, King William Country, Virginia, 2021. (Courtesy, DATA Investigations.)

Plate, Liverpool, England, ca. 1740–1745. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 9". (King William Historical Society; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Plate, Liverpool, England, 1744. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 3/4". Marks: inscribed on underside, R /• I • E • / 1744 (National Museums of Liverpool.)

Archaeological excavations at Wetherburn’s Tavern, Williamsburg, Virginia, ca. 1966. (Photo, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.)

Plate fragments, Liverpool, England, ca. 1740. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. approx. 9". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Archaeological Collections.) Cross-mended plate fragments recovered from the site of Henry Wetherburn’s Tavern (OBJ09NA-07379), Williamsburg, Virginia.

Three plates, Liverpool,England, ca. 1742. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 8 3/4". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Collections. Museum purchase and gift funds from Mr. & Mrs. Davis W. Moore.)

A RECENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL survey and test excavation by DATA Investigations llc at King William County Courthouse produced a large quantity and wide range of eighteenth-century artifacts related to a colonial-era tavern (fig. 1). The small project was commissioned by the King William County Historical Society as part of a research and public outreach initiative, with plans to curate an exhibit on taverns using local archaeological material. One of the recovered objects was a nearly complete English delft dish that has important parallels with similar plates excavated in Williamsburg, Virginia.

The King William Courthouse and the surrounding area are highly significant sites on Virginia’s Middle Peninsula. The courthouse itself was built about 1725 and is a prime example of Virginia’s rural judicial and social system that revolved around courthouse activities (fig. 2).[1] Because of their proceedings, these courthouses depended on taverns (sometimes referred to as ordinaries) and those who kept such places in business.

Little information exists about an early tavern near the courthouse except for a map from 1983 that outlines a projected location (fig. 3).[2] There are records of a John (also spelled Jon) Doncastle operating a tavern there by 1746.[3] Doncastle appears to have left approximately six years later to manage tavern keeper Henry Wetherburn’s establishment in Williamsburg (fig. 4).[4] Advertisements placed in the Virginia Gazette published in Williamsburg confirm the tavern continued to operate at least until 1780, and catered to high-ranking military officials and wealthy landowners.[5] The tavern had notable frequent visitors such as George Washington, and one could presume its archaeological material would reflect an innkeeper’s typical attempts to keep up with the latest hostelry trends in colonial Virginia.[6]

To find the tavern’s location, DATA Investigations conducted an archaeological survey east of the main courthouse area, and eventually came across a single, brick-wide foundation (fig. 5). One test unit further exposed this foundation, along with two trash-filled features, two post holes, and an extensive amount of cultural material. One of the features was a large, circular depression filled with a dense concentration of wine-bottle glass, a broken case bottle, and a wide array of ceramics including a broken delft plate (fig. 6). The plate was broken in several places but, based on its relatively flat deposition in the ground, it appears that it was nearly intact before someone discarded it. The overall quantity, quality, and diversity of drinking and dining vessels recovered from this small area is consistent with assemblages excavated at other colonial taverns across Virginia.[7]

Cleaning and mending the fragments revealed the central decoration featuring a Chinese figure standing with a vase and bowl between a large Chinese pavilion shaded by a weeping willow tree and a table containing a floral arrangement. In the background is an island with two additional buildings; the broad rim of the plate is painted with a border of alternating buildings and floral sprays. As we pieced together the fragments, we discovered even more minute details, such as an insect flying over the figure’s head. This elaborate design is suggestive of the wealthier clientele who reportedly dined at the King William tavern. Two delft plates dated 1744 from the British ceramics collections of the National Museums Liverpool in England match the border and central decoration found on the King William tavern fragments (fig. 7).[8]

The discovery of the plate was just the beginning of a more layered story. During the 1965–1966 excavations of the site of Henry Wetherburn’s Tavern in Williamsburg, Virginia, archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume recovered fragments of several British tin-glazed earthenware plates with a stylistically similar chinoiserie pattern (figs. 8, 9).[9] Analysis of the fragments revealed at least seven of these decorated plates in three sizes.[10] Mere miles from the King William tavern, this seemingly circumstantial coincidence gives rise to a more tangible connection when examining John Doncastle’s career as extrapolated from newspapers and other documentary sources.

The Virginia Gazette reveals Doncastle’s tenure as manager of a tavern in Fredericksburg in the early 1740s, and by 1746 records him as being in King William Courthouse.[11] According to the Gazette, by 1752 he was in Williamsburg renting from local resident Henry Wetherburn beginning March 1 that year; by the late 1750s he had relocated to the King William tavern. But it is clear from the newspapers and other accounts that his time managing the King William tavern or ordinary overlapped with his time at Henry Wetherburn’s Tavern.[12]

The plate fragments recovered from the site of Henry Wetherburn’s. Tavern are clearly similar to those recovered at the King William ordinary. The tin-glazed earthenware fragments from both sites include Chinese-influenced decoration with central figures and pagoda-like structures amid stylized landscapes with weeping willow trees and prunus branches, and brown or reddish-brown rims, all closely copying highly prized Chinese porcelain of the same period. The fragments from Wetherburn’s tavern are also similar to intact tin-glazed earthenware examples in the collections of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (fig. 10). One of the three plates bears the date 1742, revealing a close parallel with the 1744 dated example in the collections of the National Museums Liverpool.

Based on the dated plates of the National Museums Liverpool and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, and John Doncastle’s association with the taverns in King William and Williamsburg, it is intriguing to think that he might have played a part in selecting the plates and other dishes that outfitted the respective taverns. The King William tavern plate has an important story to reveal about its journey from England to King William County—who served meals on it, who ate from it, who washed it, and who eventually broke and discarded it. It also underscores the popularity of chinoiserie decoration in the mid-eighteenth-century decorative landscape of American colonists. Furthermore, this link helps substantiate the claim that archaeologists are close to uncovering the site of the King William tavern. The foundation uncovered might not be the tavern itself, but could represent an outbuilding near which tavern employees deposited trash. Future excavations are planned to better delineate the location of the tavern and understand its central role in life at the eighteenth-century King William Courthouse.

Alonzo Thomas Dill, King William County Courthouse: A Memorial to Virginia SelfGovernment (King William, Va.: King William County Board of Supervisors, 1984), p. 10.

Ibid., p. 31.

Virginia Gazette, July 3, 1746, p. 4.

Virginia Gazette, November 3, 1752, p. 2.

Virginia Gazette, February 4, 1768, p. 4; Virginia Gazette, February 4, 1768, p. 3.

George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, edited by Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, 6 vols. (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1979), 2:108–238; ibid., 3:40–269; Virginia Gazette, April 19, 1770, p. 3.

Robert Hunter, “English Delft from Williamsburg’s Archaeological Contexts,” in British Delft at Williamsburg by John C. Austin (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in association with Jonathan Horne Publications, 1992), pp. 26–27.

Louis L. Lipski, Dated English Delftware: Tin-glazed Earthenware, 1600–1800 (London: Sotheby Publications, 1984), p. 311, fig. 490.

Audrey Noël Hume, The Wetherburn Site, Block 9, Area N, Colonial Lots 20 and 21: Report on the Archaeological Excavations of 1965–1966. Volume II, Part 2—Ceramics: Delftware and White Saltglaze, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series RR-1180 (Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1970).

John C. Austin, British Delft at Williamsburg (London: Jonathan Horne, 1992), p. 158; Hunter, “English Delft from Williamsburg’s Archaeological Contexts” in ibid., p. 27.

Virginia Gazette, September 12, 1745, p. 4.

Virginia Gazette, November 3, 1752, p. 2; Raymond R. Townsend, Wetherburn’s Tavern Historical Report: Block 9, Building 31, Lot 20 & 21, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series 1171 (1966; Alexandria, Va.: Chadwyck-Healey, 1990), pp. 11–13.