Bass Otis, Commodore Thomas Truxtun, ca. 1817. Oil on canvas. 30 x 25". (Courtesy, Brooklyn Public Library, Center for Brooklyn History, 1974.118.)

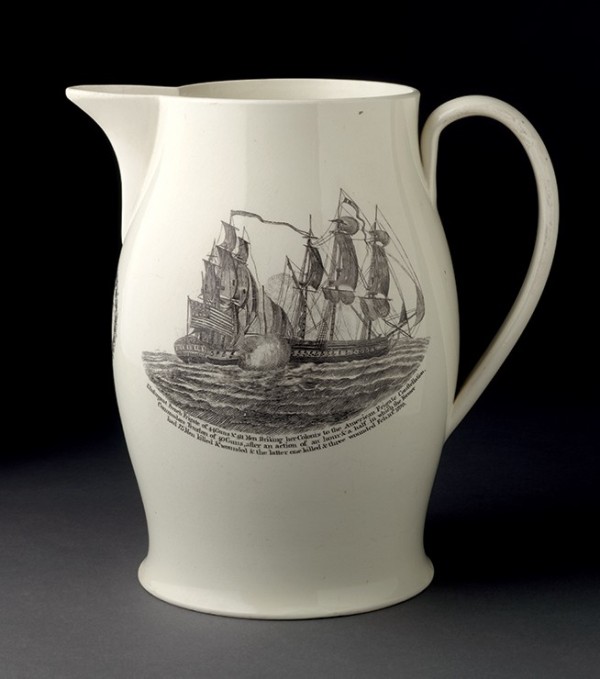

Jug showing battle between Constellation and L’Insurgente, Herculaneum Factory, Liverpool, England, ca. 1799–1810. Earthenware and lead glaze. H. 9 7/8". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum, Gift of S. Robert Teitelman, Roy T. Lefkoe, and Sydney Ann Lefkoe in memory of S. Robert Teitelman, 2009.0023.012.)

Punch bowls, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou, China, ca. 1795–1799. Hard-paste porcelain.D. of TT bowl (left) 15 3/4", D. of GW bowl (right) 15 7/8". (Naval Historical Foundation, 1949.0036.001, and Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, W-2662; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

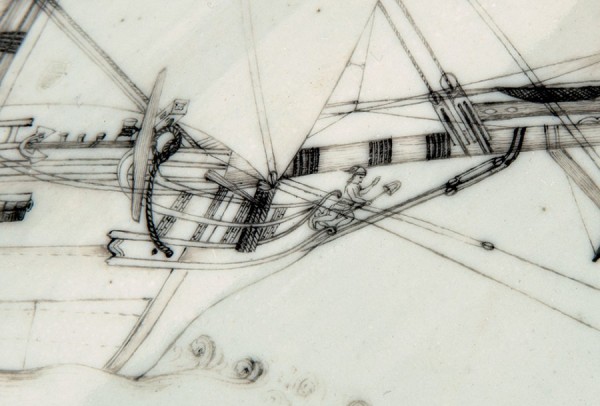

Side of the TT bowl illustrated in fig. 3, left. (Courtesy, Naval Historical Foundation, 1949.0036.001; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the border of the GW bowl illustrated in fig. 3, right. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, W-2662; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Interior of the TT bowl illustrated in fig. 3, left. (Courtesy, Naval Historical Foundation, 1949.0036.001; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Interior of the TT bowl illustrated in fig. 3, left. (Courtesy, Naval Historical Foundation, 1949.0036.001; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Interior of the GW bowl illustrated in fig. 3, right. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, W-2662; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

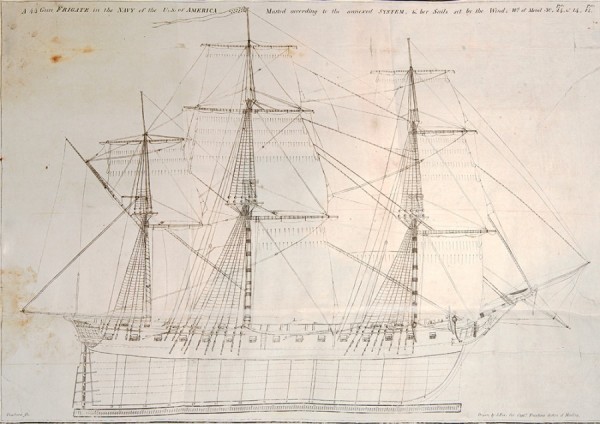

Josiah Fox, “A 44 Gun Frigate in the Navy of the U. S. of America Masted according to the present System,” plate 2 from Remarks, Instructions and Examples Relating to the Latitude and Longitude; Also the Variation of the Compass, etc. etc. etc. (Philadelphia: T. Dobson, 1794). (Courtesy, Navy Department Library, Naval History and Heritage Command; photo, Sierra Medellin.)

Edward Savage, George Washington (1732–1799), 1790. Oil on canvas, 30 5/16 x 25 3/8". (Harvard University Portrait Collection, Gift of Edward Savage to Harvard College, 1791; photo, © President and Fellows of Harvard College, H49.)

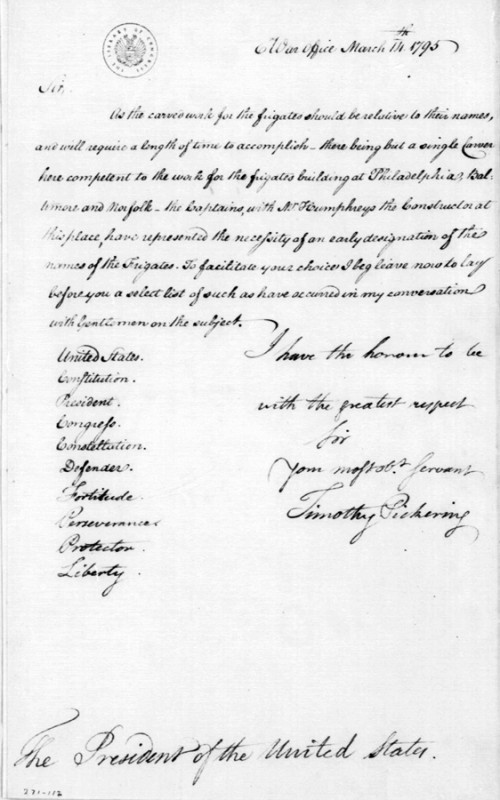

Letter from Timothy Pickering to George Washington, March 4, 1795, listing proposed names for the first frigates. (Library of Congress.)

USS Constitution, the oldest commissioned warship afloat, shown on its yearly turnaround cruise in Boston Harbor, July 4, 2011. (Photo, Charles T. Creekman.) This frigate is one of the original six of the U.S. Navy.

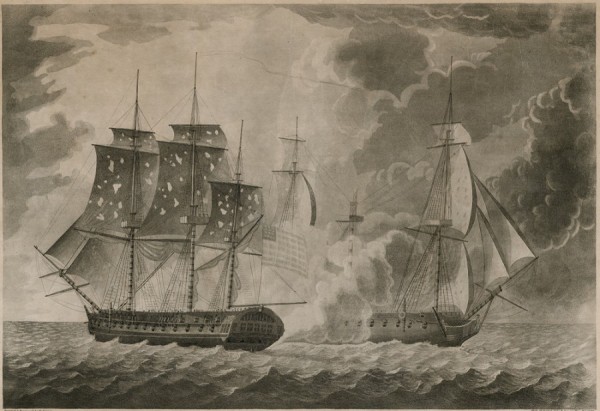

Edward Savage, Action between the Constellation and L’Insurgent on the 9th February 1799, published May 20, 1799. Aquatint; ink on paper. 15 3/4 x 21 15/16". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, M-5855.)

Detail of the figurehead of the ship on the TT bowl illustrated in fig. 3, left. (Courtesy, Naval Historical Foundation, 1949.0036.001; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Punch bowl, Jingdezhen, decorated in Guangzhou, China, ca. 1784. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 15 1/4". (Courtesy, New Jersey State Museum, CH1969.244 a, Gift of Mr. Richard V. Lindabury.) Ships decorating the wells of punch bowls were typically more modest, as is this one, in a bowl acquired by Capt. John Green of the Empress of China. The ship design was adapted from the frontispiece of a quarto-sized book, A Treatise of Practical Seamanship, by William Hutchinson (Liverpool, 1777)

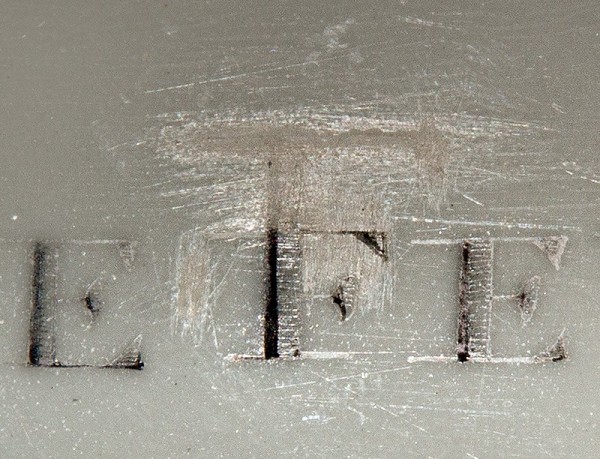

Detail of “TT” with abraded area on the pseudo-armorial of the TT bowl illustrated in fig. 3, left. (Courtesy, Naval Historical Foundation, 1949.0036.001; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Microscopic detail of the top serif of the second “T” of the cypher on the TT bowl illustrated in fig. 3, left, showing the area of erasure and the gilt over top. (Courtesy, Naval Historical Foundation, 1949.0036.001; photo, Amanda Isaac and Linda Landry.)

Detail showing the altered “F” of the GW bowl illustrated in fig. 3, right. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, W-2662; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Speculative rendering of the pseudo-armorial of the TT bowl illustrated in fig. 3, left. (Courtesy, Naval Historical Foundation, 1949.0036.001), digitally overlaid with a gilt “D” from a teabowl from another Chinese export porcelain service of ca. 1795. (Detroit Institute of Art, 1930.0307.011; digital photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

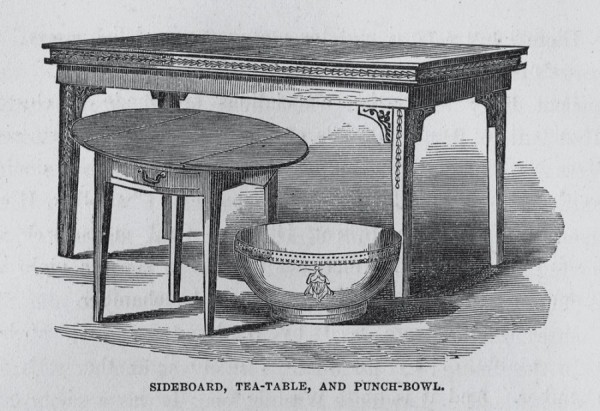

Sideboard, Pembroke tea table, and GW punch bowl. From Benson Lossing, Mount Vernon and Its Associations: Descriptive, Historical, and Pictorial (New York: W. A. Townsend & Co., 1859), p. 303. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.)

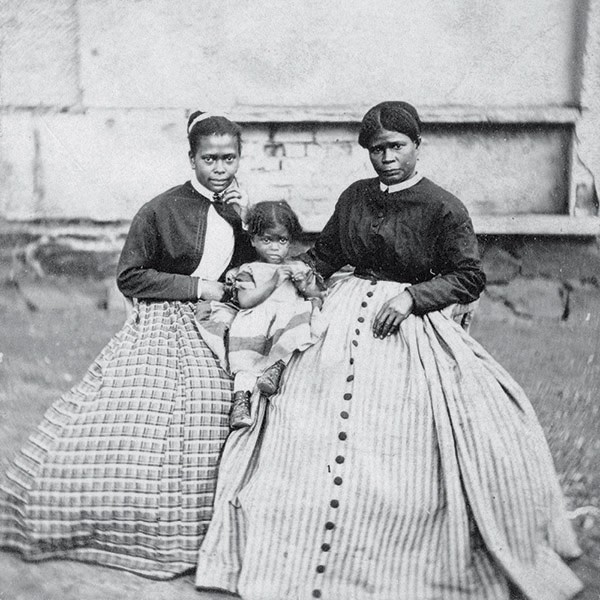

“General Lee’s Slaves, Arlington House,” believed to be Selina Gray at far right with two of

her daughters, ca. 1860s. Stereograph. 3 5/32 x 6 11/16“. (Courtesy, Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial, National Park Service, ARHO 15585.)

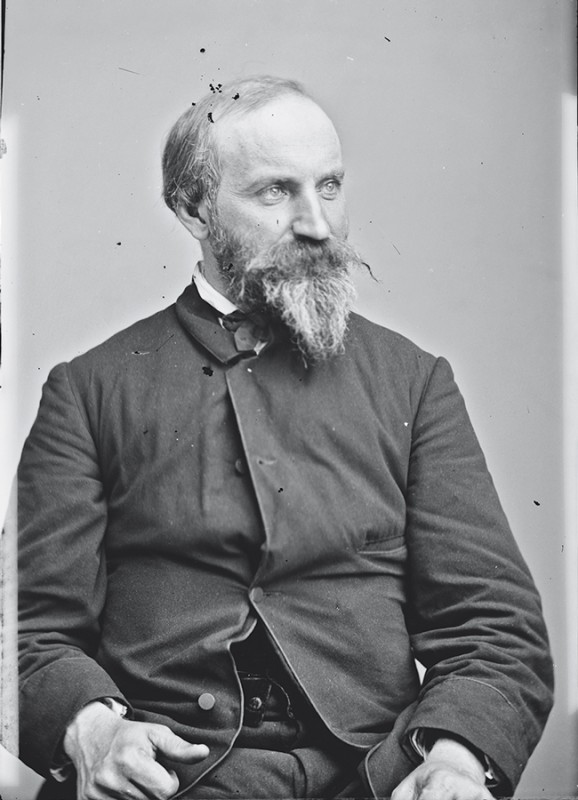

Caleb Lyon, ca. 1855–1865. (Brady-Handy Collection, Library of Congress.)

INTRODUCTION In the spring of 1799, wine and punch flowed freely to the toast of “Brave Truxtun!” among ardent Federalists and patriots throughout the United States. Captain Thomas Truxtun (1755–1822) of the American frigate Constellation, “the Vanguard of Columbia’s Naval Glory,” had captured the French frigate L’Insurgente in a hard-fought action on February 9, 1799, that proved the promise and prowess of the infant U.S. Navy in the opening stages of the Quasi-War with revolutionary France.[1] Truxtun’s victories over L’Insurgente and then, a year later, over the French frigate La Vengeance, quickly elevated him to the status of a hero in the early American popular pantheon (fig. 1).[2] His name and fame became a selling point for a host of consumer goods, from English transfer-printed earthenware and enameled porcelain cloak pins to tricorn hats and patriotic ribbons (fig. 2).[3]

Navel historians consider Truxtun to be one of the founders of the U.S. Navy for his exemplary actions, writings on naval organization and architecture, and training of officers, which brought much-needed discipline and organization in the early days of the service. The fickle winds of politics, though, removed Truxtun from the national stage and his exploits remain little remembered today outside the navy. As a result, his connection to two distinctive Chinese export porcelain punch bowls has not been fully explored (fig. 3).

The two bowls began life together in a shop in Guangzhou, China (known to Americans at the time as Canton), but were launched on separate paths soon after their arrival in the U.S. They now reside in the collections of the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association and the Naval Historical Foundation, both in the greater Washington, D.C. area. Large but not enormous, each bowl is between 15 3/4 and 15 7/8 inches in diameter. On two sides of each is a pseudo-armorial, composed of an ermine-lined blue drapery with gold fringe and tassels surrounding a shield with the gold initials of the original owners: “GW” for President George Washington and “TT” for Commodore Thomas Truxtun.[4] (Hereafter, each bowl will be referred to by its initials.) Loose sprigs of roses combined with carnations and other flowers, in blue enamel highlighted with gold, enliven the other sides. Red, blue, and gold borders decorate the rim (figs. 4, 5).

A look inside each bowl is rewarded with a pleasant surprise (figs. 6, 7). A full-rigged, late-eighteenth-century naval frigate greets the viewer, its masts, bowsprit, and spanker boom forcefully pushing out of the bowl’s well and up the sides, as if unwilling to be compassed by its porcelain sea. A U.S. Navy commissioning pennant streams out from the main mast, bearing fifteen gold stars on a blue field.[5]

The depictions of the frigates are not identical, however; the GW bowl has “DEFENDER” in black block letters below the ship; the TT bowl has no name. The enormous size of the ship design relative to the bowl makes these bowls extraordinary among the genre of ship-decorated punch bowls and porcelains, and provokes the question: What inspired their creation?[6]

In 1981, upon the first reunion of the bowls since they were made, Mount Vernon curator Christine Meadows and Naval Historical Foundation executive director, retired navy Captain David Long, researched the ship design and identified it as a copy of an engraving in Thomas Truxtun’s Remarks, Instructions, and Examples Relating to the Latitude and Longitude etc. etc. etc. published in late 1794 or early 1795 (fig. 8).[7] They surmised Truxtun as the likely commissioner of both bowls, and Meadows identified the first known documentary reference to the bowl in Martha Washington’s will, drafted in September 1800, where she specifically bequeathed “the bowl that has a ship in it” to her grandson. These two facts established a relatively narrow, window, 1795–1800, in which the bowls were ordered, created in China, and shipped back to the United States.[8] Left unanswered was the question of what motivated Truxtun to have the bowls made. Were they souvenirs of a voyage, gifts to friends or supporters, celebrations of a particular event or milestone, or a means of currying favor? This essay explores the historical context surrounding the bowls’ creation, and argues that they were no mere decorative accents for a Federal parlor, but rather products of an ambitious and far-reaching vision for personal and national advancement.

Commodore Thomas Truxtun

Victory for the colonists and their French allies in the American Revolution was the culmination of a prolonged, determined campaign. While the land battles are better remembered, maritime power was a major factor in the war. Just weeks after British General Cornwallis’s October 1781 surrender at Yorktown, Virginia, due in no small measure to France’s army and navy, General George Washington wrote to his friend and protégé the Marquis de Lafayette: “It follows then as certain as that night succeeds the day, that with out a Decisive Naval force we can do nothing definitive, and with it, every thing honourable and glorious.”[9]

At the time of the American Revolution, the French navy had the only ships capable of challenging the British navy in line-of-battle combat where two opposing fleets sailing in a column or line were able to fire their broadside guns at each other without endangering friendly ships. The sacrifice of maneuverability for firepower led to ships of the line typically mounting at least seventy cannon. A ship of that size had never been built in the American colonies, and the Americans had no hope of obtaining or building enough of them to be able to meet the British fleets on an equal footing. Accordingly, the Americans turned to commerce raiding rather than direct engagement with British naval power whenever possible. Undaunted by the odds, the fledging Continental Navy, together with governmentchartered privateers (private individuals authorized by Congress to seek out and capture British vessels) carried out sustained operations against British commerce throughout the conflict. This sufficiently exasperated British leaders and made eventual settlement of the conflict more pressing to that global empire. Among the intrepid privateers was a young captain from Hempstead, New York, named Thomas Truxtun.

Orphaned at age ten, Truxtun was apprenticed in 1767 to the captain of a British merchant vessel, beginning a three-and-a-half-decade career at sea. Impressed into the Royal Navy in 1771, as Britain was dealing with its first crisis over the sovereignty of the South Atlantic Falkland Islands, Truxtun was able to return to the merchant fleet soon thereafter when the diplomatic standoff was settled short of war with Spain. His brief exposure to Royal Navy organization, customs, and traditions had a lasting influence on his thoughts about shipboard routine, training, and discipline.[10]

By 1775, all of twenty years old, Truxtun married and was the master of his own vessel, the Charming Polly, in New York. With the colonies already in a state of rebellion against British authority, and on just his third trading voyage in that ship, Truxtun was captured in the Caribbean by a Royal Navy sloop-of-war. With his vessel and cargo condemned and sold as a prize of war, Truxtun made his way to Philadelphia where he successfully joined the crew of the newly fitted-out privateer Congress for her first voyage in early 1776. Nearly two years later, after successful cruises in that ship and two subsequent vessels he commanded, he shifted back to the merchant fleet to meet the pressing need for war supplies for the struggling new nation. That duty was equally dangerous, and by the close of the war he had distinguished himself at sea and gained a reputation as a knowledgeable seaman and excellent leader.

On March 17, 1782, with the war’s end in sight, Truxtun attended a public dinner in Philadelphia for General George Washington. As Truxtun himself later recalled, Washington reportedly acknowledged Truxtun’s valuable contributions to American victory by declaring him to have “been as a regiment to the United States,” in effect saying Truxtun’s actions, in diverting British ships and curtailing the delivery of war materiel to the British, were equivalent to the advantage gained by a regiment of more than four hundred soldiers opposing the enemy.[11] Over the years, Truxtun and Washington appear to have forged an amicable professional relationship, born of a sense of common cause in their country’s revolutionary beginnings and shared Federalist political views, with a strong commitment to national defense.

Peace brought a postwar military drawdown and sell-off of Continental Navy ships, as well as a surge in American commercial voyages worldwide, unfettered by British trade constraints but unprotected by British naval power. Truxtun was heavily involved in that trade expansion, and over the next decade he captained several ships, including the appropriately named Canton, which in late 1785 embarked on one of the earliest American voyages to China. His series of successful cruises—to China (1785–1787 and 1787–1789) and India (1789–1791 and 1791–1793)—brought back valuable cargoes of tea, cotton, and porcelain to eager consumers, and solidified his reputation for reliability among the international merchant community.[12] Being in London in the spring of 1794 placed him in position to do a favor for President George Washington: to bring home a gold watch and chain ordered for Mrs. Washington.[13]

1794 proved to be a pivotal year for Truxtun and the as-yet-unborn U.S. Navy. The new nation’s expanding maritime commerce had been under attack for several years in the Mediterranean Sea by Barbary Coast corsairs (state-sponsored privateers from Algiers and Tripoli). Belatedly recognizing the need to protect its merchant shipping, and with the Continental Navy ships long gone, in March 1794 Congress passed “An Act to provide a Naval Armament,” authorizing six frigates to be built.[14] Six maritime ports along the eastern seaboard, from Maine to Virginia, were selected as shipbuilding sites—in recognition of both the need for broad political support for such an expensive national undertaking, as well as the reality of limited manpower and ship construction timber and other resources in any one port.[15]

By June 1794 President Washington had appointed the commanding officers for the six frigates, intending that each supervise the building of his own ship (fig. 9). Truxtun, the most junior and the only one of the six who had not served in the Revolutionary War as a Continental Navy officer, was assigned to the 36-gun ship to be built in Baltimore, Maryland.

Naval architect Joshua Humphreys was responsible for the excellent hull designs for the frigates. However, the placement and height of their three masts and the location and length of the yards that held the sails (collectively known as spars) was openly debated by Humphreys and the captains of the six ships from June 1794 to January 1796. At issue was whether the United States could design a ship to compete with the British (and potentially the French) navy. Calculating that any American warship could only hope to be victorious in a single-ship engagement with another frigate, Humphreys designed his American frigates to exceed the size and hull strength of a typical British or French frigate, and to possess the sailing capabilities and speed to evade a heavier gunned ship or any group of enemy ships his frigates might encounter.[16] Wind-powered sails being the only feasible means of motive power in the late eighteenth century for open ocean voyages, designating the size and location of the masts and the size of the yards and their positions on those masts was paramount. Truxtun forcefully expressed his views on the subject to his five fellow frigate captains, the Secretary of War, and the President. He soon met with stiff opposition from Joshua Humphreys who, having reviewed Truxtun’s system, summarily dismissed it as “erroneous.”[17]

Despite his lower naval rank, Truxtun had more than twenty years of at-sea experience and an undiminished ambition. He was determined to share his organizational and navigational knowledge broadly in order to shape the structure of the new navy—specifically the design of those first six ships. To this end, he sent a brief but pointed letter to Secretary of War Henry Knox (the secretary of the navy position would not be established until 1798) in which he stressed his opinion that the new frigates should have masts and their associated yards sized and placed according to his calculations. At the same time, he was also compiling a manuscript to broadcast his knowledge of sailing and his views on ship design, titled “Remarks, Instructions, and Examples relating to the Latitude and Longitude etc etc etc.”[18] To illustrate his masting system, Truxtun commissioned Josiah Fox (who was already working as Humphreys’s assistant) to produce a diagram that he intended to publish together with a printed copy of his letter to Knox in the book. “Let me have it as soon as possible, and attend to the dimensions here enclosed of all the spars,” wrote Truxtun to Fox in November 1794, promising “When you have done, I will make you a present of a handsome piece of India cloth for your wife.”[19] For Truxtun, the use of commodities as payment or payback was familiar, and it seems likely this was neither the first nor last time he would leverage his access to desirable Asian exports. Little did Fox realize that his side-view image of a notional 44-gun frigate hull incorporating Truxtun’s masting design was destined to live long after the men involved had passed from the scene.

In 1795 Timothy Pickering, Knox’s successor as secretary of war, had a brief, one-year tour in that position but played several key parts in the frigate saga. First, he distributed copies of Truxtun’s book with its masting image to the other five frigate commanding officers.[20] Washington also received a copy of Truxtun’s work, possibly from Pickering though it may have been a gift directly from Truxtun.[21] Second, Pickering presented to President Washington a selection of ten possible names for the six frigates (fig. 10). Washington’s response to this naming opportunity has not been found, but five of those initial names would in fact be bestowed on the ships—President, Congress, United States, Constellation, and Constitution.[22] Among those not used was Defender.[23]

Pickering optimistically asked Humphreys and Captains Truxtun, Barry, and Talbot to “consult together” and prepare a unified opinion on the masting and sparring of the ships, but that never materialized. When Pickering’s successor as secretary of war, James McHenry, took office in early 1796, a circular from his office ended the debate by simply announcing that the six sets of captains and shipbuilders “shall have liberty to Mast and Spar their own Ship.”[24]

1796 brought unexpected disruption to the frigate-building plans. A peace accord with Algiers triggered a provision of the original naval act that threatened to halt all ship construction, since the perceived foreign naval threat would be diminished. Truxtun realized that his low seniority could derail his career should a likely compromise with Congress result in only a few of the six ships being completed. Turning to President Washington, Truxtun wrote an impassioned plea to be able to both complete and command his Baltimore-built frigate: “I shall take a particular pleasure, in exerting my utmost abilities, to have her speedily compleated, and in a way that will do honor to the United States.”[25]

Washington was indeed able to convince Congress to complete construction of three of the six frigates with an April 1796 act authorizing that work. Furthermore, he confirmed that the captains for the three ships being built in Boston, Philadelphia, and Baltimore would remain as originally assigned, Truxtun among them (fig. 11).

As work progressed on his 36-gun frigate, Truxtun remained in Baltimore but continued to think beyond that busy shipyard scene and contemplate the naval operations to come. He had already included in his earlier book his recommendations for the general duties of each officer aboard a warship, based on his years at sea and his familiarity with Royal Navy routine. Now he turned to the complex challenge of communicating between ships with flags in that pre-electronic era. Once again considering himself to be the standard-setter for this young navy, he published a signal book in 1797.[26]

Truxtun successfully completed Constellation (to the specifications of his masting system, of course) and launched the frigate in September 1797.[27] By June 1798, he proudly reported that she “goes through the Water with great Swiftness.”[28] Cruising in the Caribbean to protect American shipping, Truxtun and his well-trained crew on Constellation fought and captured French frigate L’Insurgente (fig. 12). President John Adams exclaimed, “I wish all the other officers had as much zeal as Truxton.”[29] The Merchants and Underwriters at Lloyd’s Coffeehouse of London presented Truxtun with an elegant silver urn in thanks for his efforts in preserving merchant shipping from harassment by the French. At Mount Vernon, Washington received tangible reminders of Truxtun’s victory from artist Edward Savage, a pair of prints depicting the chase and engagement.[30] Although retired from the presidency, Washington had returned to the military stage as commander in chief of the Provisional Army, authorized by President Adams over concern of open war with France.

The Point of Crisis

The years in which the bowls must have been ordered and created (1795– 1800) were tumultuous, to say the least, for both Truxtun and the nation. When set against this context, it seems most likely that Truxtun commissioned the pair of bowls when the future of his career and the navy were hanging in the balance (1795–1797), and when he most needed President Washington’s support and backing.

Punch Bowls as Gifts

By the 1790s, the custom of giving punch bowls as gifts was already well established, particularly among hard-drinking mariners who welcomed the opportunity to imbibe punch and toast the success of their ventures. As centerpieces of the convivial table, punch bowls offered a welcome means of celebration and refreshment, particularly in the male environs of the captain’s quarters, officers’ mess, or the gentlemen’s club, fostering social and business relationships around the shared drink. By the mid-18th century, Liverpool potteries catered to their merchant and maritime clientele, offering tin-glazed earthenware and later creamware punch bowls customdecorated with ships, some of which were gifts for masters and owners.[31]

By virtue of their relative rarity and the skill of Chinese painters, punch bowls of Chinese export porcelain developed a reputation as desirable gifts. A 1779 report by officers of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (Dutch East India Company) stated that punch bowls “with the factory . . . which are now and then brought in by private individuals must be considered as rarities, which one makes a present of to friends in one or twos . . . .”[32] John Green, captain of the Empress of China, the first American ship to travel to China, brought back “1 tubb containing 4 factory painted bowles” which were probably intended as gifts to family, friends, or business associates.[33]

Custom-decorated bowls could be tailored to particular occasions or messages. A punch bowl decorated with a stock image of a ship labeled Grand Turk was reportedly given to Captain West of the Grand Turk, by Pinqua, a Chinese porcelain dealer who had risen to become a hong merchant, one of the select group authorized to secure and manage trade with foreigners.[34] The bowl gift may have been an apt means of fostering the new business relationship with the U.S. traders. A later punch bowl commissioned by General Jacob Morton of New York left no doubt as to its purpose. The inscription around the exterior described the occasion and recipient: “Presented by General Jacob Morton, to the Corporation of the City of New York, July 4th, 1812.” On the interior, together with a view of New York Harbor, is the exhortation, “Drink deep. You will preserve the City and encourage Canals.” At the time, Morton was serving as the clerk to the city council. His gift, a lasting memorial of his political interests, was reportedly used for many years by city officials at public banquets.[35]

Truxtun’s bowl for President Washington lacked an inscription, but it seems to have had a similar purpose as a lobbying gift. Its decoration speaks volumes. The full-size design on the interior showcased the proposed 44-gun frigate, the new class of ships that would be the projected glory of the United States, and offered a convenient prompt to raise a toast to its future. More specifically, it advertised Truxtun’s theories and contributions to the force.

The name given to the ship is also telling. “Defender” was one of the proposed names for the six frigates, and Truxtun intended it as a clear compliment to Washington. In the years following the Revolution, individuals and groups regularly applied the title “Defender” to Washington, alluding to his role both as a warrior and a statesman. In 1789 the ladies of Trenton proclaimed that Washington, the “Defender of the Mothers will also Protect their Daughters,” on an archway under which he traveled on the way to the inauguration.[36] The people of Boston saluted President Washington as the “Defender of their Freedom and Independence” during his northern tour, and the officials of Charleston, South Carolina, addressed the “Defender of the liberties of America” during his southern tour.[37] After his appointment as commander in chief in 1798, friends and associates congratulated him and addressed him again as “Defender of your Country.”[38]

Launching the Bowls

Truxtun, heavily engaged with the fitting out and launching of his frigate, Constellation, did not make a voyage to China between 1795 and 1800, but instead presumably entrusted his instructions and a copy of the engraving to a friend or associate sailing for Guangzhou during that time. Typically arriving with the summer monsoon winds between June and September, a ship and her crew had 3–6 months in port before making the return voyage in the winter months. Following customary practice, the order would have been placed with a Chinese merchant soon after arrival in the hope that the order would be completed by the time the ship was ready to sail. If not, it would have to wait for a ship returning the next season.[39]

In Guangzhou, Truxtun’s agent probably would have gone to a merchant who specialized in porcelain to commission the bowls, someone like Yam Shinqua, “CHINA-WARE MERCHANT at Canton,” who advertised in the Providence Gazette in 1804 that he “BEGS Leave respectfully to inform the American Merchants, Supercargoes, and Captains, that he procures to be manufactured, in the best Manner, all Sorts of CHINA-WARE, with Arms, Cyphers, and other Decorations (if required) painted in a very superior Style, and on the most reasonable Terms. All Orders carefully and promptly attended to.”[40]

Many of the porcelain merchants and others who catered to foreign traders were located on Jingyuan Jie (“Profoundly Tranquil Street”), known to foreigners as Porcelain Street, China Street, New Street, or New China Street. It ran perpendicular to the river and the quay in front of the hongs, or factories, the large buildings in which European, American, and other foreign merchants lived, worked, and stored their goods.[41]

In the porcelain shop, Truxtun’s agent would have provided the Chinese merchant with the engraving of the ship and the text for the inscriptions, chosen a border pattern, and discussed the size and overall design of the bowls, the price, and the date of completion. The discussion would have taken place through a Chinese interpreter or in a pidgin English that likely would have included some Chinese vocabulary and phrases.

Once agreed upon, the Chinese merchant would pass the designs and instructions on to a painter, who either worked on the premises or in a nearby workshop. He would paint the designs in overglaze enamels onto porcelain blanks, and then fire them in a muffle kiln, which melted and fixed the enamel decoration onto the surface of the bowls.

The Chinese artist meticulously copied the engraving, capturing all the details of Truxtun’s masting and sparring system. The detailed care with which the artist painted is also seen in the figurehead, a figure of Liberty wearing a winged cap and holding a liberty cap on a pole (fig. 13). In place of the dotted scale lines that appear below the waterline in the original engraving, the artist painted rolling waves.

Notably, the painter rendered the ship at the same scale as the engraving instead of reducing it to fit in the center of the well, as was more common on ship-decorated bowls (fig. 14). Comparison of the measurements of the painted designs on both bowls with that of the original engraving shows that the painted version varies by only 5/16" at most. This visual hyperbole, where the design nearly overwhelms the surface of the bowl, might have been the choice of the painter, who thus avoided having to change the scale of the engraving. It is possible, though, that it was intentional, directed by Truxtun at the outset to ensure that the ship and the ideas it represented could not be missed.

Truxtun’s Surprise, or a Hasty Reversal

Depending on the ship’s schedule, the time between the ordering of the bowls and their delivery would have been 1–2 years. Excited as Truxtun must have been to receive the bowls, it appears he had a shock when he unpacked them.

Visual examination of the TT bowl shows a notable difference in the finish color around the initials on each shield (fig. 15). Microscopic examination confirmed the reason: a series of abrasions made with a sharpedged tool had removed areas of gilding and red enamel, and cut through the glazed surface to reveal the porcelain body (fig. 16). Examination of the GW bowl revealed a change had been made in like fashion to the “F” in “Defender” (fig. 17).

It appears that Truxtun’s agent failed to accurately convey some important details of the bowl’s design. Trusting instructions to an intermediary is a risky business, especially considering the distance, the number of people involved, and the linguistic and cultural differences, all of which provide ample opportunities for misunderstandings and mistakes. In this case, evidently the bowl had originally been painted with the initials “TD” (fig. 18). After scraping off the unwanted loop, the repairer then added additional gold to extend the top serif of the T and added additional flourishes. On the GW bowl, the repairer scraped off the top of an “F,” indicating that the original title had been lettered like a French word, “De Fender.” The repairer then extended the original middle stroke, to create the top serif, and added a new middle stroke.

To date, no other example of this type of alteration has been identified on Chinese export porcelain of this period. The crudeness and apparent hastiness of the alteration suggests the changes took place in the United States, after receipt of the bowls, rather than at the workshop in Guangzhou.[42] If that is the case, it would suggest that Truxtun, after discovering the mistakes, took the bowls to a china painter in Philadelphia, New York, or Baltimore to make the corrections. In the case of the GW bowl, the fact that an otherwise small lettering error was altered further indicates the significance of the bowl as a presentation piece. The correction ensured that Truxtun’s intended compliment to Washington was received. In the case of the TT bowl, it seems reasonable to suppose that Truxtun would not have wished to retain a bowl with the wrong initials in his home. The change raises the question of whether someone other than Truxtun was the original intended recipient. While the possibility is intriguing, it seems unlikely, as no one has been identified who had a “TD” monogram and was associated with the American voyages to Canton of that period.

A Punch Bowl for the President

Truxtun likely presented the corrected bowl to Washington sometime between 1796, while Washington was still president, and the fall of 1799, by the time of Truxtun’s final dinner with Washington on September 12.[43]

Whether the bowl arrived, was corrected, and presented in the midst of the crisis over the establishment of the navy or afterward, the GW bowl effectively kept Truxtun’s name, achievements, and availability for command ever visible to the commander in chief, a strategy Truxtun may have considered necessary since he did not yet have any brilliant naval victories to his name. In this he followed the pattern of numerous authors, artists, and artisans who gave gifts to Washington to advertise their abilities and services. If so, Truxtun’s choice was akin to the comte de Custine’s 1782 gift of a porcelain service to Mrs. Washington, decorated with the laurel-crowned cypher of Washington. It honored the victorious general, but it also reflected glory back on the giver of the gift: with Custine’s service, the different patterns on each of the pieces attested to the quality and virtuosity of wares from his Niderviller porcelain factory, advertising his goods to an American market that had been newly opened to France after the colonies’ break with England.[44]

Glass entrepreneur and German immigrant John Frederick Amelung used a similar tactic after establishing a glass factory in New Bremen, Maryland. In March 1789 he personally traveled to Mount Vernon and presented “two capacious goblets of double flint glass, exhibiting the General’s coat of arms, &c.” Even before the presentation, Washington seems to have heard of Amelung’s efforts and was promoting him as a “capitol artist” whose industry would benefit from Washington’s own pet project, the establishment of the Potomac canal to connect eastern manufacturers with western markets. Four months after the visit, Washington approved a ten percent duty on glass imports, to protect infant industries like Amelung’s glass factory.[45]

Washington scrupulously avoided a system of official patronage, but by virtue of his position and reputation, his endorsement, albeit unofficial, was golden, and his table and home were necessarily public stages, showcasing objects, their makers, and givers worthy of emulation and support. While the precise moment and nature of the gift to Washington remains elusive, in themselves, the two punch bowls defined the essence of the message Truxtun sent. By twinning, he materially linked the two households, the commodore’s and the president’s, and linked his own fortunes to those of his perceived patron.

The GW bowl would have had plenty of opportunities for use after its presentation, both in the president’s residence and in retirement at Mount Vernon. As was customary, the Washingtons served punch both as a refreshment to guests arriving in between meals or during times of celebration.[46] In the executive residence, hired steward Frederick Kitt would have overseen the service of punch. At Mount Vernon, the enslaved butler Frank Lee directed the preparation of rum punch and the filling of the bowl for the constant stream of visitors in those years, including extended family, friends, political and business connections, and admirers from around the world.

The bowl’s chance to display Truxtun’s merits as a seaman and philosopher did not last long. With Washington’s death on December 14, 1799, Truxtun lost his strongest political ally. Within a few years, the bowl transformed from a politically energized centerpiece to a relic of an American legend.

Truxtun’s Exit

Returning to the United States as a hero in March 1799 following his victory over L’Insurgente, Truxtun became embroiled in a debate on his seniority in relation to the other navy captains, and resigned on August 1st. After some months, and the dinner with Washington, he resolved his differences and returned to command of the Constellation. Underway the day before Christmas 1799 and headed to the Caribbean once again, Truxtun’s most significant naval exploit lay just ahead. Engaging the more heavily armed French frigate La Vengeance in early February 1800 during a bloody battle that lasted long after sunset, Truxtun claimed victory when his badly damaged opponent limped away under cover of darkness. Once again the nation extolled Truxtun’s accomplishments. Congress voted him a gold medal—the first such Congressional award since the Revolutionary War.[47]

The years following Truxtun’s last meeting with Washington were stormy. Now a national hero for his at-sea exploits, Truxtun was in line to command a forward-deployed squadron of U.S. Navy ships in the Mediterranean Sea when, in early 1802, his pugnacious personality reasserted itself in an unfortunate manner. Threatening to “quit the service” again if navy leadership would not acquiesce to his request to have a flagship captain appointed to the ship in which he would cruise, Secretary of the Navy Robert Smith called his bluff and accepted his resignation.[48] In the years that followed, Truxtun returned time and again in letter and publication to his perceived poor treatment by the navy and the nation, but was not returned to active service. “Were Washington now alive,” he railed in 1806, “what must have been his astonishment at the alacrity with which the present administration embraces a poor pretext to throw out of office, a man, who, thirty-nine years since, came into naval life.”[49]

Later Travels of the TT Bowl

The deaths of George Washington in 1799 and Martha in 1802 launched the two punch bowls on separate but equally fascinating voyages of their own through the 225 years since their creation.

Truxtun lived in retirement in New Jersey and later in Pennsylvania. He never returned to sea and therefore missed participating in the War of 1812 with Great Britain—a conflict that saw the six frigates in action and many Truxtun-trained officers winning victories at sea. Truxtun, in his final public service, was elected sheriff of Philadelphia County from 1816 to 1819. Meanwhile, the TT bowl settled down in Truxtun’s home among a large collection of trophies, such as the silver urn presented by Lloyd’s, and luxuries brought back from China and India, described by one visitor as his “Eastern Magnificence.”[50] It might have taken center stage on visits from old friends like John Barry or celebratory occasions, such as the weddings of his daughters.

Truxtun died in 1822 and was buried in Philadelphia. His legacy of training, organization, and valor at sea remains alive in a series of six U.S. Navy warships named Truxtun, whose active service has spanned 180 years of our nation’s history. The current namesake, a guided missile destroyer DDG103, was commissioned in 2009.

The TT bowl descended to Truxtun’s eldest daughter, Sarah Truxtun Benbridge. Her descendants’ relocation to Indiana took the TT bowl out of sight for nearly eighty years, during which period the connection of the bowl’s image with Truxtun’s book was forgotten. His descendants came to believe it depicted his China Trade vessel Canton. In 1949 Truxtun’s great-great-grandson Richard Wetherill Benbridge donated the bowl to the Naval Historical Foundation in Washington, D.C.[51]

“down to the hull”

Upon her death in 1802, Mrs. Washington bequeathed “the bowl that has a ship in it” to her only grandson and male heir, George Washington Parke Custis (1781–1857), together with all the family silver, portraits, and the Society of Cincinnati and States china.[52] The punch bowl’s inclusion among these dynastic objects suggests Mrs. Washington saw it as part of the conveyance of family identity, wealth, and status. Washington had no children of his own, but had adopted George Washington Parke Custis, the son of John Parke Custis, Martha Washington’s son from her first marriage, and the boy had grown up in the presidential households and at Mount Vernon. As a teenager he had witnessed the construction of the frigate United States in Philadelphia with Washington, and likely would have been familiar with, if not present at, the presentation of the bowl by Truxtun.[53] Washington, who had worked hard to assist his ward in finding a profession, secured Custis an officer’s commission in the Provisional Army.[54]

In the years to come, Custis touted his filial relationship to Washington and used his collection of Washington relics, the “Washington treasury,” at his home, Arlington, to undergird and boost his own social and political status. Presenting himself as a gatekeeper and mediary of Washington’s values, he brought out artifacts as showpieces at his entertainments.[55] The GW bowl appears to have been one of the relics that saw regular use on those occasions. Col. John N. Macomb Jr. (1811–1889) recalled how Custis used the bowl to close the nightly merriment surrounding the wedding festivities of Sydney Smith Lee in 1834. Eleanor Harris, the enslaved housekeeper at the time, likely oversaw the use of the bowl, the preparation of the punch, and its safekeeping during this time.[56] As Macomb later told it, “Every night before the party retired punch was bounteously dispensed from a punch-bowl which had belonged to General Washington. In the bottom of the bowl was a painting of a ship, the hull resting in the bottom, the mast projecting to the rim. The rule was to drink down to the hull—a rule strictly observed.”[57] The ship’s purpose had initially promoted one man’s reputation and vision for a faster, stronger navy, but a generation after its presentation, all that was forgotten. Instead, the ship in the bowl now served as a convenient excuse to imbibe even more.

Later Travels of the GW Bowl

Custis’s frequent use of the bowl made it familiar to Arlington guests and intimates of the family. Historian Benson Lossing brought the bowl to the attention of a national audience, first by spotlighting it in an article in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine in 1853, and then in his book Mount Vernon and Its Associations in 1859 (fig. 19). The illustration enlarged the bowl, visually exaggerating its importance and making it appear to be half the size of the standard Pembroke table with which it was paired. Lossing’s description clearly identified all of the essential elements of decoration: “It is pure white porcelain, with a deep blue border at the rim, ornamented with gilt stars and dots. In the bottom is a picture of a frigate, and on the side are the initials G. W. in gilt, upon a shield with ornamental surroundings.”[58] Its fame established, thereafter the bowl could not easily pass as anything other than what it was, Washington’s own punch bowl.

Following Custis’s death in 1857, his daughter, Mary Custis Lee (1807– 1873), inherited and cared for the bowl until 1861. After her husband, Robert E. Lee (1807–1870), decided to join the Confederacy that spring, the United States army planned to occupy Arlington. In addition to being considered the property of a rebel, the plantation occupied a strategic position overlooking Washington, D.C. Forewarned by her husband and preparing for departure, Mary Lee had important Washington and Custis family artifacts, including the furniture, paintings, and silver, packed and sent to family and friends for safekeeping. Optimistically thinking she would return, she left behind numerous other pieces of the “Washington treasury,” including the Society of the Cincinnati porcelain purchased by Washington, the States porcelain service given to Mrs. Washington, and the Defender punch bowl. She locked them in the cellar and entrusted their care to Selina Gray (1823–1907), her enslaved housekeeper (fig. 20).[59]

At some point in the seven months between the initial Union occupation of Arlington on May 28, 1861, and January 7, 1862, both the cellar and the attic were breached and the contents began to be dispersed. Selina Gray reported the burglary to General Irvin McDowell, who first officially reported to headquarters on the status of the Washington relics in his letter of January 7, 1862. McDowell explained that “last week the Hon. Caleb Lyons [sic], being here on a visit and learning of these facts [the burglary], expressed a wish to see this china, as having frequently been a guest of Mr. Custis he was well acquainted with everything in his possession which had belonged to General Washington.”[60] A poet and acclaimed lecturer, Lyon (1822–1875) had parlayed his rhetorical talents and social connections into occasional stints of public service, serving, among other short posts, a term in the U.S. Congress from 1853 to 1855 (fig. 21). Lyon also avidly collected historical curiosities, contemporary paintings, and porcelain, and had an eye for the main chance.

McDowell reported the results of Lyon’s inspection, describing the Washington relics and, for corroboration, referencing Lossing’s descriptions and illustrations. As for the punch bowl: “General Washington’s punch bowl, with the picture of a ship in it, . . . was here but a short time before (as I am informed by those who saw it in the cellar,) but has been stolen.” It was almost certainly Gray’s testimony as well as that of the other enslaved men and women still at Arlington that corroborated the initial presence of the bowl. McDowell, noting the national importance artifacts and their endangerment in the unsecured house, particularly with the “crowd of curiosity seekers constantly coming here,” advocated for the transfer of the remaining relics to the Patent Office or Smithsonian.[61] The news was widely reported, highlighting Lyon’s role in the discovery of the “priceless prize.”[62] Lyon was asked to superintend the transfer of the objects, and on January 28, the National Republican reported that the relics had been “artistically arranged by Caleb Lyon” at the Patent Office.[63] While this select group of objects had been secured for the Union and posterity, a significant number of artifacts had effectively been looted, including the punch bowl, and made their way into private hands.[64] The hunt was on for those knowing enough to obtain a piece of Washington history.

Twenty years later, the bowl reappeared in the 1882 catalog of the auction of Lyon’s estate, described as “Punch bowl belonging to Geo. Washington, has been carefully repaired; ornamented with his initials on the side.”[65] Circumstantial evidence suggests that Lyon may have stolen the bowl outright in 1862, having had both motive and opportunity—he had been at Arlington and had been in charge of the relics around the time the bowl and several other pieces went missing, and he was an “antiquarian, vigorous and insatiable.”[66] To be fair, it is also possible that the bowl had been taken prior to Lyon’s arrival and inventory, and that he later hunted it down, and had no compunction about acquiring it as his own rather than returning it to the U.S. government.

Lyon’s embezzlement of government funds while governor of Idaho (1864–1866), among other controversies, finally forced his retirement from public life, but along the way he had amassed a respected collection of historical bric-a-brac and porcelain. The sales of his collection, in 1876 and 1882, drew the attention of the leading Americana and porcelain collectors of the time.[67] Even though broken and repaired, Washington’s punch bowl took top dollar at the 1882 auction, selling for $320 to an unnamed buyer, bested only by the paintings.[68]

Thereafter, the bowl rested in private hands, enjoying a relatively quiet existence after the tumultuous war years.[69] In the early twentieth century, the bowl descended to Major Carlos de Zafra (1882–1967), a naval architect and engineer, who could well appreciate the finely drawn rendering of the frigate. He served briefly as the curator of shipbuilding and navigation at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, caring for exhibits on the development of navigation and the collection of ship models.[70] If he recognized the design of the ship in the bowl, he unfortunately left no record of it. His son, Robert de Zafra, inherited the bowl, and in a 1973 letter of inquiry to the Association shared his observations of it with then curator Christine Meadows, noting that the ship was “carefully drawn in profile, rather like a naval architect’s rendering,” and correctly dating the bowl based on the fifteen-star pennant.[71] Meadows confirmed the bowl’s Washington history, and de Zafra generously loaned it to the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association in 1975.

The bowl’s public display in Mount Vernon’s museum proved fortuitous. In 1981 Evan Randolph IV, a descendant of Thomas Truxtun, visited Mount Vernon and recognized the Washington bowl as the pair to one that had descended in his family and was on display at the National Museum of the United States Navy.[72] Through Randolph’s efforts, the two bowls were reunited and studied. Working together, Meadows and Captain David Long, the first executive director of the Naval Historical Foundation, rediscovered the source of the ship design in Truxtun’s book. The next year, Susan Detweiler published the story of the two bowls in her seminal work, George Washington’s Chinaware, placing it in the context of Washington’s relationship with ceramics, his consumer choices, and the gifts he received.[73] In 2018 the late Robert de Zafra and his wife, Dr. Julia M. P. Quagliata de Zafra, gave the bowl to Mount Vernon in furtherance of their abiding interest in preserving the history of the United States. As a result, their gift enabled further study of the bowl and this article.

Conclusion

Now that it is properly situated against the backdrop of Truxtun’s own career and the historical context of the late 1790s, the Washington bowl can be seen more clearly as a calculated political gift, not just a neutral decorative object. The twin bowls were created at a time of great uncertainty, for Truxtun personally and for the nation as a whole, when the concept of a standing navy was controversial and yet to be decided. In commissioning the bowls and giving one to the president and commander in chief, Truxtun seems to have been using every means he could to sway or solidify Washington’s opinion, to gain support for his own career and the establishment of the U.S. Navy. With the death of Washington and the removal of the bowl from its prominence on Washington’s table, Truxtun’s gift lost its original influence, and instead became an artifact of a fascinating period of American history. The ship in the bowls—the result of Truxtun’s concept, Fox’s drawing, and a Chinese porcelain painter’s skill—ultimately outlived Truxtun’s short-term personal goals and endowed both bowls with a timeless patriotic appeal that transcended the political maneuvering of the early republic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This article would not have been possible without the joint support of the Naval Historical Foundation (NHF) and the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association (MVLA). At the NHF, Rear Admiral Edward Masso and Dr. David Winkler enthusiastically encouraged the reunion and analysis of the bowls at Mount Vernon. Mark Weber and Wesley Schwenk of the National Museum of the United States Navy assisted with our research and ensured that the TT bowl was transported with special care, while Christian Higgins and Megan Casey of the Navy Department Library enabled us to examine copies of Truxtun’s book and provided measurements of the original engraving. At Mount Vernon, Dr. Susan Schoelwer, Adam Erby, and Mary Thompson shared their own research and provided important feedback and critiques. Samantha Snyder filled countless interlibrary loans and tracked down obscure sources, and Dawn Bonner searched for and scanned images. Lori Trusheim conserved the GW bowl, and Linda Landry captured clear microscope views of the alterations on both bowls. Dr. Erich Uffelmann of Washington and Lee University generously donated his time and expertise to perform XRF analysis on the bowls’ enamels. Finally, we are deeply grateful to Ron Fuchs for encouraging the writing of this article, and to him, Hannah Boettcher, and Dr. Cassandra Good for sharing their extensive research and knowledge.

Eugene S. Ferguson, Truxtun of the Constellation: The Life of Commodore Thomas Truxtun, U.S. Navy, 1755–1822 (1956; reprint, Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000), p. 171.

The most demonstrative example of this is Truxtun’s inclusion in the gallery of portraits of distinguished Americans organized by Joseph Delaplaine in Philadelphia. Brooklyn before the Bridge: American Paintings from the Long Island Historical Society (New York: Brooklyn Museum, 1982), p. 86. Bass Otis’s portrait of Truxtun shows him wearing the badge of the Society of the Cincinnati, to which Truxtun was admitted as an honorary member in New York on July 4, 1800, following his naval victories. John Schuyler, The Institution of the Society of the Cincinnati (New York: Douglas Taylor, 1886), p. 85.

In the collection of Winterthur Museum, among others, are examples of the Liverpool jugs and mugs (2009.023.012, 2009.023.009, 1968.0083), the Staffordshire blue transferware American Naval Heroes series (1958.1842), and cloak pins (labeled Truxtun but bearing the image of Lord Nelson (1965.2407.002). For the hats and ribbons, see the advertisement of Benjamin S. Judah & Brothers, Commercial Advertiser, New York, January 6, 1800, p. 1, and Ferguson, Truxtun of the Constellation, p. 171.

By naval tradition, the title “commodore” is assumed by an officer assigned to command more than one ship. Although an officer’s rank for pay purposes might be captain, commanding a squadron of ships, as Truxtun did during the Quasi-War, entitled him to be addressed as commodore while in command and after relinquishing command as an honorary title.

A commissioning pennant is a long streamer in some version of the national colors of the navy that flies it, which serves as the distinguishing mark of a commissioned vessel in many navies. The pennant is flown at all times as long as a ship is in commissioned status, except when a flag officer or civilian official is embarked and flies his personal flag in its place.

David Sanctuary Howard, “The Sailing Ship on Chinese Porcelain: A Brief Survey, 1700–1850,” Catalogue of the Ellis Memorial Antiques Show (Boston: Ellis Memorial Antiques Show, November 1977), pp. 45–54; Ron Fuchs II, “Ahoy! Ship Bowls in Pottery and Porcelain,” paper presented at Winterthur Ceramics Conference, April 16, 2010.

Thomas Truxtun, Remarks, Instructions and Examples Relating to the Latitude and Longitude; etc. etc. etc. (Philadelphia: T. Dobson, 1794).

“Reunion at Mount Vernon,” Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association Annual Report (1975), pp. 18–23; “Family Reunions,” Pull Together: Naval Historical Foundation Newsletter 21, no. 2 (Fall 1981): 1.

George Washington to the Marquis de Lafayette, 15 November 1781, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745–1799, 39 vols. (Washington, D.C.: U.S. GPO, 1937), 23:341. See also “From George Washington to Marie-Joseph-PaulYves-Roch-Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, 15 November 1781,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/99-01-02-07408.

The details of Truxtun’s life and career are taken from Ferguson, Truxtun of the Constellation, the seminal biography on Truxton.

Thomas Truxtun, Reply of Commodore Truxtun to an Attack Made on Him in the National Intelligencer in June, 1806 (Philadelphia, 1806), p. 25.

Ferguson, Truxtun of the Constellation, pp. 60–99; Jean Gordon Lee, Philadelphians and the China Trade 1784–1844 (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1984), pp. 21, 28; Jean McClure Mudge, Chinese Export Porcelain for the American Trade: 1785–1835 (Wilmington: University of Delaware Press, 1962), pp. 98–100. Numerous newspaper advertisements attest to the variety of cargoes he brought back for merchants. See, e.g., advertisement for Mordecai Lewis & Co., Independent Gazetteer, Philadelphia, May 23, 1787, p. 3, and advertisement for Meeker, Cochran & Co., Dunlap’s American Daily Advertiser, Philadelphia, April 23, 1794, p. 2.

Tobias Lear to George Washington, 12 February 1794, The Papers of George Washington Digital Edition, 13 February 1794 entry, Tobias Lear account, 4R, Ledger C, George Washington Ledger of Accounts, Lloyd W. Smith Collection, Morristown National Historical Park.

Dudley W. Knox, ed., Naval Documents Relating to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers. Vol. 1: Naval Operations, Including Diplomatic Background from 1785 through 1801 (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1939), pp. 69–70.

The construction of the frigates is ably described at length in Ian Toll, Six Frigates: The Epic Founding of the U.S. Navy (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2006).

Joshua Humphreys to Robert Morris, 6 January 1793, Joshua Humphreys Papers: Letter Book 1793–1797, Historical Society of Philadelphia.

Joshua Humphreys to Thomas Truxtun, n.d. [late 1794–early 1795], p. 69, Joshua Humphreys Papers: Letter Book 1793–1797, Historical Society of Philadelphia.

Truxtun, Remarks, Instructions and Examples, Appendix, pp. i–ix and accompanying plate.

Thomas Truxtun to Josiah Fox, 21 November 1794, Josiah Fox Papers, Manuscript Collection MH-11, Phillips Library, Peabody-Essex Museum, Salem, Mass.

National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 45, Naval Records Collection of the Office of Naval Records and Library, Records of the War Department, 1790– 1831, Letters Sent Concerning Naval Matters, October 1790–June 1798, entry 374 (M739).

George Washington’s copy of Truxtun’s book, signed by Washington on the flyleaf, is currently in the collection of the Boston Athenaeum.

Timothy Pickering to George Washington, 14 March 1795, The Papers of George Washington Digital Edition. Those first five names described the new republic’s unique attributes, with “Constellation” referring to the Continental Congress’s Flag Act of 1777: “Resolved, That the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.” Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., Journals of the Continental Congress 1774–1789, 34 vols. (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1904–1937), 8:464.

The U.S. Navy did not commission a ship with the name Defender for nearly 200 years, until September 1989, when mine countermeasures ship MCM-2 joined the fleet.

Knox, Naval Documents Related to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers, 1:128.

Thomas Truxtun to George Washington, 4 February 1796, The Papers of George Washington Digital Edition.

Thomas Truxtun, Instructions, Signals, and Explanations, offered for the United States Fleet (Baltimore, Md.: John Hayes, 1797). The only known extant copy, Truxtun’s personal copy, is in the Navy Department Library.

While the historic ship currently on display in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor is indeed the former USS Constellation, it is not the 1797 frigate commanded by Truxtun but rather the 1854 sloop-ofwar with a proud history of its own in antislavery patrols and Civil War service. For a full history, see Dana M. Wegner, Fouled Anchors: The Constellation Question Answered, Technical and Administrative Services Department Research and Development Report (Bethesda, Md.: David Taylor Research Center, September 1991); available online at https://www.navsea.navy .mil/Portals/103/Documents/NSWC_Carderock/fouled_anchors-1.pdf.

Knox, Naval Documents Relating to the United States Wars with the Barbary Powers, 1:133.

“From John Adams to Benjamin Stoddert, 22 April 1799,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-3453.

Edward Savage to George Washington, 17 June 1799, The Papers of George Washington Digital Edition.

Rina Prentice, A Celebration of the Sea: The Decorative Art Collection of the National Maritime Museum (London: The Stationary Office, 1994), pp. 8–10; Bernard Watney and Caroline Roberts, “Liverpool Porcelain Ship Bowls in Blue and White,” Transactions of the English Ceramic Circle 15, pt. 1 (1993): 1–23.

Quoted in Christiaan Jörg, Porcelain and the Dutch China Trade (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1982), p. 128.

Philip Chadwick Foster Smith, The Empress of China (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Maritime Museum, 1984), p. 294.

William Sargent, Treasures of Chinese Export Ceramics from the Peabody Essex Museum (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2012), pp. 401–2; Robert E. Peabody, The Log of the Grand Turks (Cambridge, Mass.: Riverside Press, 1926), 94. On Pinqua’s career, see Paul A. Van Dyke, “Yang Pinqua, Merchant of Canton and Macao, 1747–1795,” Revista de Culture (2020): 62–89.

David Sanctuary Howard, New York and the China Trade (New York: New-York Historical Society, 1984), pp. 114–15; Mary E. Nealy, “A Remarkable Old Punch Bowl,” Clay Worker 31, no. 5 (May 1899): 429.

“From George Washington to the Ladies of Trenton, 21 April 1789,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-02-02-0095.

Boston Gazette, 26 October 1789, cited in Timothy H. Breen, George Washington’s Journey (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016), p. 130; “From George Washington to the Officials of Charleston, 3 May 1791,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov /documents/Washington/05-08-02-0117.

“To George Washington from William Heth, 13 July 1798,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-02-02-0316; “To George Washington from John Trumbull, 18 September 1798,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0006.

Ronald W. Fuchs II with David S. Howard, Made in China: Export Porcelain from the Leo and Doris Hodroff Collection at Winterthur (Winterthur, Del.: Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, 2005), p. 31.

“Advertisement.” Providence (R.I.) Gazette 41, no. 2106, May 12, 1804: [3]. Readex: America’s Historical Newspapers. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.ezproxy.wlu.edu/apps /readex/doc? p=EANX&docref=image/v2%3A10380B58EB4A4298%40EANX-1056B5A3F0A CE334%402380089-1056B5A430002EEE%402-1056B5A4E6F5C343%40Advertisement.

Paul van Dyke and Maria Kar-wing Mok, Images of the Canton Factories 1760–1822: Reading History in Art (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2015), p. xvii.

I am indebted to William Sargent, Dr. Christiann Jörg, Angela Howard, and Ron Fuchs for their expert review and opinion on this case. XRF analysis of the areas on each bowl that had been repainted, conducted by Dr. Erich Uffelman of Washington and Lee University, confirmed that there was no significant difference in the composition of the gilding used on the lettering of the TT bowl or on the enamel of the GW bowl in those areas.

While the exact date of the presentation cannot be determined, it seems most likely to have occurred prior to the September 1799 dinner. Truxtun could not have anticipated that final meeting with enough time to order the bowl for the occasion. The first documentary mention of the bowl is Martha Washington’s September 1800 draft of her will.

Susan Gray Detweiler, George Washington’s Chinaware (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1982), pp. 67–76.

The goblets remain unlocated. Dwight P. Lanmon et al., John Frederick Amelung: Early American Glassmaker (Corning, N.Y.: Corning Museum of Glass, 1990), p. 30; “Extract of a letter from a gentleman in Alexandria, to the edition hereof, dated March 28, 1789,” Pennsylvania Packet, 10 April 1789; “From George Washington to Thomas Jefferson, 13 February 1789,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/ Washington/05-01-02-0219.

Contemporary accounts indicated that President Washington typically had punch served on significant holidays during his presidency. Abigail Adams referenced the Washingtons serving punch to a large number of guests on July 4 during the presidency, while Senator William Maclay mentioned a bowl of punch as part of the New Year’s Day refreshments. “Abigail Adams to Mary Smith Cranch, 23 June 1797,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/04-12-02-0103. Senator William Maclay, as quoted in William Spohn Baker, Washington after the Revolution, 1784–1799 (Philadelphia, Pa.: J. B. Lippincott, 1898), p. 204. I am indebted for these references to Mary Thompson and her research on holidays and foodways in the Washington household.

Chris Neuzil, Lenny Vaccaro, and Todd Creekman, “Captain Truxtun’s Congressional Medal,” Numismatist 120, no. 2 (February 2007): 32–41.

Ferguson, Truxtun of the Constellation, p. 224

Truxtun, Reply of Commodore Truxtun to an Attack Made on Him, p. 26

As quoted in Katherine M. Beekman, “A Colonial Capital: Perth Amboy, and its Church Warden, James Parker,” Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society n.s., 1/III (1918):14.

The TT bowl was exhibited at the Naval Historical Foundation’s Truxtun-Decatur Museum at historic Decatur House near the White House in downtown Washington, D.C., and later was placed on loan to the Navy in the National Museum of the U.S. Navy at the Washington Navy Yard in southeast D.C., where it remains displayed today. Naval Historical Foundation Accession Card # 49-36-1. Chinese porcelain bowl with “TT” monogram for Thomas Truxtun, donated 28 November 1949 from Mr. “Weatherow Bendridge.” [actually Mr. Richard Wetherill Benbridge]; Information on Thomas Truxtun’s porcelain bowl provided by Mr. Richard Benbridge Wetherill of Lafayette, Indiana, on 23 January 1940. Naval History and Heritage Command’s (NHHC) ZB file in Navy Department Library; Maria S. B. Chance, A Chronicle of the Family of Edward F. Beale of Philadelphia (Haverford, Pa.: 1943), p. 78.

John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Last Will and Testament of George Washington . . . the Last Will and Testament of Martha Washington (Mount Vernon, Va.: Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, 1992), p. 56.

George Washington Parke Custis recalled visiting the Philadelphia Navy Yard in an 1844 letter to a descendant of naval architect Joshua Humphreys. George Washington’s diary mentions visiting the yard on at least one occasion, January 2, 1796. See Henry Humphreys et al., “Who Built the First American Navy?,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 40, no. 4 (1916): 390–91; Diary entry: 2 January 1796, The Papers of George Washington Digital Edition. https://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/GEWN-01-06-02-0005-0001-0002.

“From George Washington to James McHenry, 14 December 1798,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/06-03-02-0181.

For a cogent analysis of George Washington Parke Custis’s use of social and cultural capital, and his conscious crafting of the Washington legacy as well as his own identity as a child of Mount Vernon, see Cassandra Good, “Washington Family Fortune: Lineage and Capital in Nineteenth-Century America,” Early American Studies (Winter 2020): 90–133; and Seth Bruggeman, “‘More than Ordinary Patriotism’: Living History in the Memory Work of George Washington Parke Custis,” in Remembering the Revolution: Memory, History, and Nation Making from Independence to the Civil War, edited by Michael A. McDonnell et al. (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2013), pp. 127–43.

Email correspondence with Cassandra Good, 25 January 2022; and Mary Grassick, “Historic Furnishings Report: Arlington House” (Washington, D.C.: National Park Service: 2016), pp. 41–42.

A. L. Long, The Memoirs of Robert E. Lee (New York: J. M. Stoddart & Co., 1886), p. 38.

Benson Lossing, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 40, no. 8 (September 1853): 440. The bowl is also mentioned in an obituary for Custis: “The Late G. W. P. Custis,” Harper’s Weekly (October 24, 1857): 68.

Grassick, “Historic Furnishings Report: Arlington House,” p. 33.

“Mount Vernon Relics,” Report, House of Representatives, 41st Congress, 2d Session, Report #36, p. 2.

“Mount Vernon Relics,” Report, House of Representatives, 41st Congress, 2d Session, Report #36, pp. 1–2.

“Relics of the Washington Family,” The Press, Philadelphia, January 14, 1862.

“The Washington Relics,” National Republican, Washington, D.C., January 28, 1862.

These included a Custis family Bible, a Martha Washington dress, and numerous pieces of Society of Cincinnati porcelain. Ruth Preston Lee, “Mrs. General Lee’s Attempts to Regain Her Possessions after the Civil War,” Arlington Historical Society Magazine 6 (1978): 28–35; T. Michael Miller, “The Mystery Surrounding G. W. P. Custis’ Painting of George Washington at Yorktown,” Alexandria Chronicle 6, no. 4 (Fall 1998): 1–11.

George A. Leavitt & Co., Catalogue of porcelains, and various objects of art, furniture, etc. . . . the whole belonging to the estate of the late Governor Caleb Lyon . . . (New York: George A. Leavitt & Co., 1882), lot 17, p. 12 (Washington Library, Mount Vernon, Virginia).

“Relics of the Washington Family,” The Press, Philadelphia, January 14, 1862.

Alice Morse Earle cited the selling prices at the Lyon sales as the benchmark for china prices in the late nineteenth century. See Alice Morse Earle, China Collecting in America (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1892), pp. 124, 203, 239, 254, 346; and James Grant Wilson, “About Bric-à-Brac,” Art Journal n.s., 4 (1878): 314.

“Art Objects at Auction: Sale of the Caleb Lyon Collection of Porcelains, Bric-a-Brac, and Paintings,” New York Times, January 26, 1882.

A Mary Hathaway of New Bedford, Massachusetts, owned the bowl in 1899. This was likely Mary B. Hathaway (1841–1916), daughter of William H. Hathaway Jr. (1798–1885). Upon her death, the bowl passed to her friend Emma de Zafra Roderick (d. 1930), and thence to her son, Major Carlos de Zafra. In 1934 antique dealer Charles Woolsey Lyon (no direct relation to Caleb), acting as agent for the owner, offered to sell the bowl to the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association for $1,200. Operating with limited funds due to the Depression, the MVLA declined. See Memorandum of C. W. Lyon, 15 February 1934; Letter of C. W. Lyon to Miss Annie B. Jennings, 15 February 1934; Robert de Zafra to Christine Meadows, 28 April 1973; Meadows to de Zafra, 20 May 1973, and de Zafra to Meadows, 15 June 1973, Curatorial File for W-2662. I am indebted to Dr. Susan Schoelwer for her genealogical research identifying Mary Hathaway.

S. M. O’Connor, “Who was Major Carlos de Zafra?,” In the Garden City blog, https:// inthegardencity.com/2018/04/24/who-was-major-carlos-de-zafra-by-s-m-oconnor/#_ftn2.

Robert de Zafra to Christine Meadows, 28 April 1973, Mount Vernon Curatorial File for W-2662.

“Family Reunions,” Pull Together: Naval Historical Foundation Newsletter 21, no. 2 (Fall 1981): 1.

Detweiler, George Washington’s Chinaware, pp. 149–53.