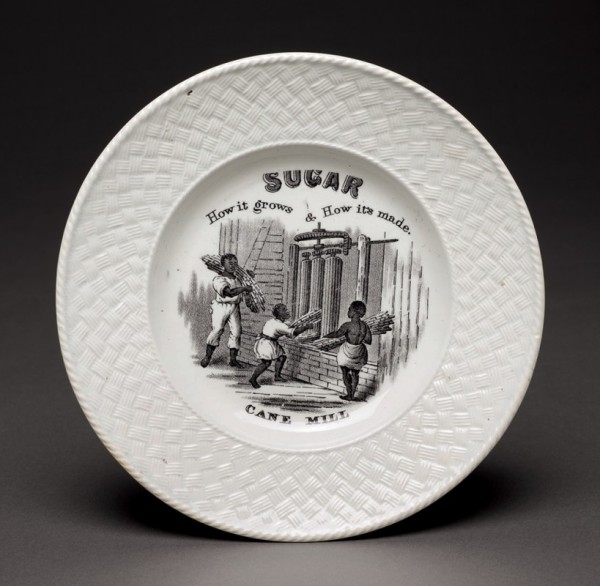

Plate, possibly John Carr & Son(s), North Shields, Northumberland, England, ca. 1854–1861. Lead-glazed white earthenware, black enamel. D. 7 1/8". Marks: on the obverse, “SUGAR / How it grows & How it’s made. / CANE MILL”; printed “G” on the reverse. (Historic Deerfield, Museum Collections Fund, 2020.3.1; photo, Penny Leveritt.)

Detail of the printed “G” mark on the reverse of the plate illustrated in fig.1

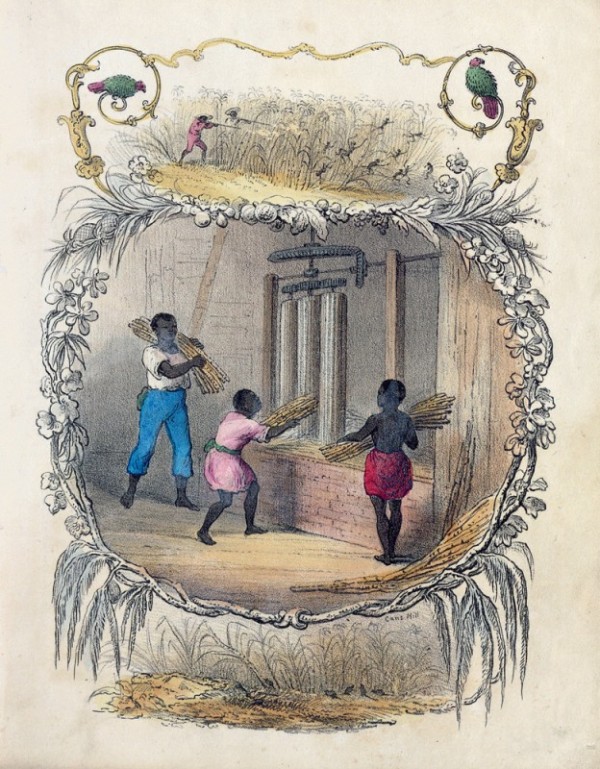

“Cane Mill,” from J.L.S., Sugar: How It Grows, and How It Is Made: A Pleasing Account for Young People (London: Darton and Clark,ca. 1845). (Courtesy, Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington.) This engraving served as the design source for the transfer-printed scene on the plate illustrated in fig. 1.

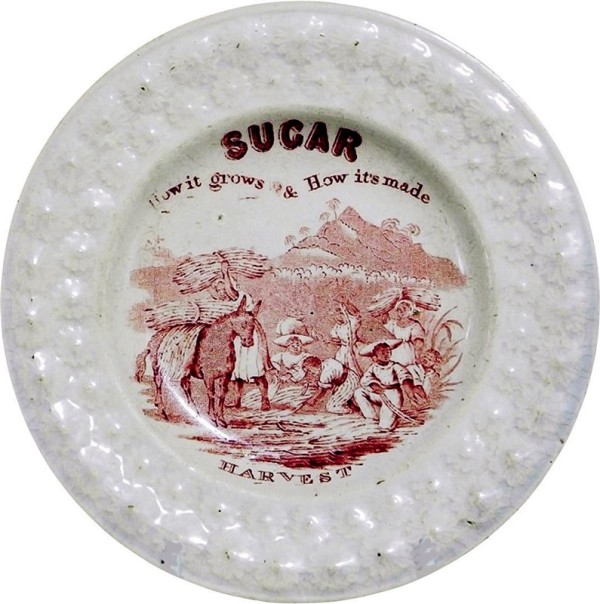

Plate, John Carr & Sons, North Shields, Northumberland, England, ca. 1861. Lead-glazed white earthenware, red enamel. D. 8 1/4". Marks: on obverse, “SUGAR / How it grows & How it’s made / HARVEST”; impressed on reverse, “JOHN CARR & SONS” with anchor and stag’s head. (Courtesy, Transferware Collectors Club Database of Patterns and Sources.)

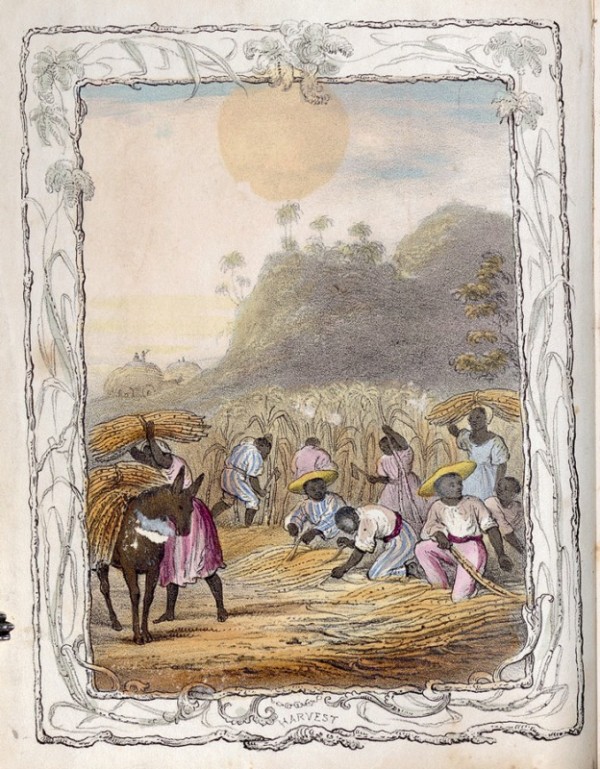

“Harvest,” from J.L.S., Sugar: How It Grows, and How It Is Made: A Pleasing Account for Young People (London: Darton and Clark, ca. 1845). (Courtesy, Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.) This engraving served as the design source for the transfer-printed scene on the plate illustrated in fig. 4.

Plate, John Carr & Co., North Shields, Northumberland, England, ca. 1850. Pearlware, polychrome enamels. D. 8 1/4". Marks: on obverse, “SUGAR / How it grows & How it’s made / OPEN PAN BOILING”; reportedly impressed on reverse, “J. CARR & Co” (Courtesy, Kinghams Auctioneers.)

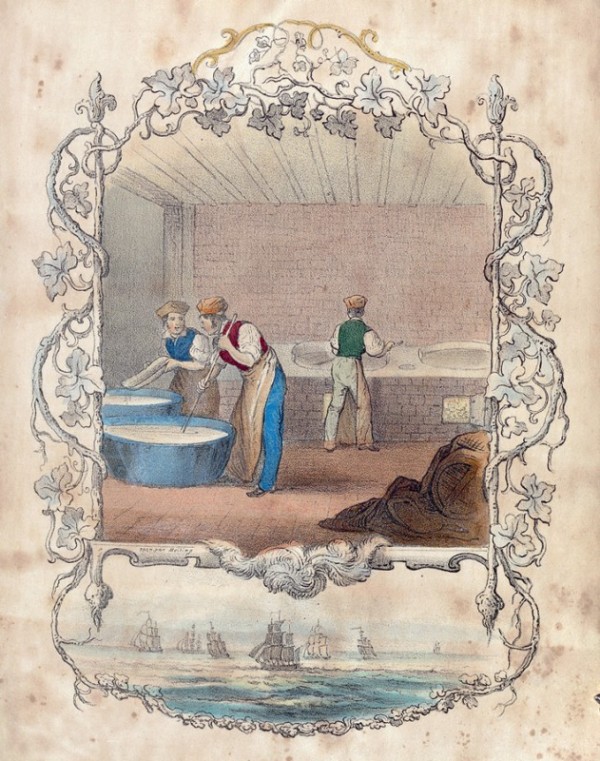

“Open Pan Boiling,” from J.L.S., Sugar: How It Grows, and How It Is Made: A Pleasing Account for Young People (London: Darton and Clark, ca. 1845). (Courtesy, Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana.) This engraving served as the design source for the transfer-printed scene on the plate illustrated in fig. 6.

Plate, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1838. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 10 1/2". Marks: on rim, “FREEDOM FIRST OF AUGUST / 1838”; on flag, “LIBERTY” (Historic Deerfield, Museum Collections Fund, 2020.28; photo, Penny Leveritt.) The emancipation of the enslaved in the British West Indies on August 1, 1838, was commemorated on a number of British ceramics, such as this plate. Although a cause for celebration, emancipation did not immediately end the struggles of the formerly enslaved in the British West Indies.

IN AUGUST 1838, Epaphras Hoyt (1765–1850) of Deerfield, Massachusetts, recorded in his diary the momentous events unfolding in the British West Indies some 1,700 miles to the south:[1]

This morning early, our people were roused from their slumbers by the brisk ringing of our village bells. Some not knowing the cause, ran to their doors expecting to hear the cry of fire! Not so! The news soon circulated of the fact of the total emancipation of slavery in the British West India Islands, on the 1st of August 1838. What a glorious event in the annals of Great Britain! That Nation under an hereditary monarchy, has nobly stepped forward and emancipated half a million of their fellow beings, from the chains and lashes of their assumed masters![2]

The town of Deerfield’s more ardent anti-slavery activists, as noted in the writings of the Rev. Samuel Willard (1775–1859), also marked the occasion with hymns and speeches. Willard privately contemplated emancipation’s transformative effects, noting how the formerly enslaved were raised “from death to life” and elevated from “things” to “human beings”:

When in 1838 the slaves in the British West Indies were on the first of August set free, nearly all the family either sat up till midnight, or rose at that hour, and sang a hymn prepared for the occasion; and, if I ever felt devout, I believe it was then, filled as I was with the thought, that in that hour more than seven hundred thousand men arose from death to life,—were transformed from things into human beings. . . . At my instance that day was solemnized in Deerfield by a meeting of those who were interested in the occasion, and appropriate speeches were made.[3]

Notwithstanding the enthusiastic optimism of Willard, Hoyt, and others who celebrated Britain’s Emancipation Act, emancipation did not immediately cease the struggles of the formerly enslaved in the British West Indies. A transfer-printed plate, a recent addition to Historic Deerfield’s British ceramics collection and the subject of recent research, documents that reality as well as the experiences of the formerly enslaved living in the British West Indies in the aftermath of emancipation (fig. 1).

When Historic Deerfield acquired the plate in 2020, the plate’s connection to post-emancipation life in the British West Indies was unknown. Indeed, very little was understood about the plate itself. Its size and subject matter suggest it had been made for a child or young person, but an older audience is possible.[4]

The plate’s transfer-printed scene, titled “SUGAR / How it Grows & How it’s made. / CANE MILL,” appears to show a group of enslaved individuals processing sugar cane. Because the plate depicts only one step in the process of refining sugar—running sugar cane through a cane mill—it was believed to have been part of a set illustrating the sugar-refining process as a whole. The scene had likely been copied directly from an engraving in a book or other printed publication, as was common for many transfer-printed designs of this period, but the design source had not been identified. Although the plate was marked with a printed “G” on its reverse, its maker was also unknown (fig. 2). However, the plate’s design and subject matter indicated it had been produced in England circa 1850, just over ten years following emancipation in the British West Indies.

The printed scene was initially understood to convey an anti-slavery message. Potteries might have created the plate’s message with that in mind, or perhaps purchasers imbued it with that meaning. The subject of sugar and sugar production was closely connected with the anti-slavery movement in Britain. As a product produced by enslaved persons, West Indian sugar was boycotted by some anti-slavery activists as early as 1791.[5] Activists’ refusal to buy these products led them to seek out substitutes, such as those marked “East India Sugar Not Made by Slaves” or “East India Sugar. The produce of Free Labour”—phrases inscribed on several English ceramic and glass sugar bowls made 1820–1830.[6] In this context, the plate’s scene might have been designed, or interpreted by some, to highlight or denounce the dangerous work that enslaved persons of various age groups were forced to endure while working on sugar plantations.[7]

On the center of the plate, several persons of color, an adult and possibly two children, are shown feeding stalks of sugar cane into a three-roller grinding mill. These mills crushed the freshly cut stalks in order to extract the plant’s juices. Accidents were not uncommon, including the loss of limbs, as workers were forced to work quickly and for long periods so that the juices did not spoil.[8] In this view, one of the child’s hands is extended precariously close to one of the rollers. The danger conveyed in the scene may have encouraged some to relinquish sugar entirely, or at least to seek out an alternative.

The treatment of enslaved men and women on sugar plantations was addressed in British anti-slavery publications as well. For example, a scene similar to the one depicted on this plate (see fig. 1) was employed in an earlier anti-slavery pamphlet written by Amelia Opie titled The Black Man’s Lament: Or, How to Make Sugar (1826). The book recounts, in poetic verses, the sad tale of the capture of Africans in their native homeland, and their transport to the West Indies to labor on sugar plantations. One of the book’s engravings depicts enslaved persons feeding cane into a grinding mill. Drawing attention to the plight of the enslaved, Opie explains how workers are forced to constantly toil and feed the mill:

That mill, our labour, every hour,

Must with fresh loads of canes supply;

And if we faint, the cart-whip’s power,

Gives force which nature’s powers deny.[9]

For laborers, work on a sugar plantation was usually fast-paced, dangerous, and physically exhausting, and plates of this nature might have been used to teach young people about that grim reality.

The plate’s production some ten or more years following emancipation in the British West Indies does not rule out the possibility that it was made by British pottery makers, or that buyers interpreted the plate’s scene with anti-slavery notions in mind. Indeed, in the aftermath of emancipation, many in England continued to fight for the end of slavery abroad, and British potteries continued to cater to that market by producing ceramics with explicit anti-slavery scenes and messages.[10] For example, the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, established in 1839, worked for “the universal extinction of Slavery and the Slave-trade.”[11] In order to accomplish that goal, they sought, among other things, “to open a correspondence with Abolitionists in America, France, and other countries, and to encourage them in the prosecution of their objects by all methods consistent with the principles of this Society.”[12] In addition to illustrating the hardships of slavery, then, the plate might have signified the work that still needed to be done in the international fight against slavery.

The American abolitionists whom the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society sought to aid may have interpreted the plate’s scene in a similar light. Although it is unknown whether these plates were available in America, American abolitionists—some of whom also boycotted sugar produced by enslaved persons—may have also interpreted the plate’s scene as a criticism of enslaved labor.[13] Those activists might have been reminded of enslaved persons laboring on sugar plantations in the South, including in the state of Louisiana. Louisiana sugar plantations utilized equipment similar to the mill depicted on this plate, and discussions and images of this equipment—and the sugar production process more generally—found its way into popular publications.[14] Similarly, the plate’s scene may have also reminded American anti-slavery activists of information they had encountered in abolitionist literature. For example, Solomon Northup (b. 1807/8), a free Black who was captured, enslaved, and then later released, described in his book Twelve Years a Slave (1853) not only his experience working on a sugar plantation as an enslaved person, but also the equipment that was used to process the sugar, including the “two great iron rollers” used for crushing the cane.[15] Therefore, as owners or purchasers encountered the scenes on these types of plates, they may have recalled scenes of slavery they had seen or read about elsewhere. In doing so, they possibly assigned meanings to these objects that supported their anti-slavery beliefs or efforts, and used them either as domestic ornaments or tools to educate young people about sugar making and the horrors of slavery.[16]

The recent discovery of the plate’s design source, however, served to greatly expand the plate’s interpretation. The transfer-printed scene was copied from an engraving, “Cane Mill,” in the book Sugar: How It Grows, and How It Is Made: A Pleasing Account for Young People by “J.L.S.” (identity unknown) (fig. 3).[17] Published in London about 1845 by Darton & Clark, the book can be classified under a type of literary genre that historian Elizabeth Massa Hoiem describes as the “production story.”[18] A product of the late eighteenth century, these stories provided young people with illustrations and information—oftentimes quite detailed and technical— concerning the production of a variety of goods and materials.[19] However, the book’s possible inclusion in the collection of the Mercantile Library of Baltimore in 1851 suggests that the market extended to an adult audience.[20] In the book, the author provides readers with detailed descriptions of the sugar cultivation process, particularly on the island of Jamaica, as well as the processes for producing refined sugar. The book’s eight hand-colored engravings supplement the text by illustrating various stages of the production process.

Two other transfer-printed plates are known whose design source was prints copied from Sugar, including one titled “Harvest” and the other “Open Pan Boiling,” suggesting that these plates formed sets (figs. 4, 5, 6, 7).[21] Plates with the “Cane Mill” scene, however, survive in greater numbers with different molded borders, suggesting that it was the most popular.[22] The “Harvest” and “Open Pan Boiling” examples are larger in size (approximately 8 1/4" in diameter) than the current example of “Cane Mill,” and are different in decoration. The “Harvest” plate is transfer-printed in red, and features a molded “daisy” border; the “Open Pan Boiling” plate is transfer-printed in black, and features a molded border with polychrome painted roses. Both plates seem to be by the same maker: the “Harvest” plate bears the mark of John Carr & Sons of North Shields, Northumberland, England; and the “Open Pan Boiling” plate reportedly is also marked “J. Carr & Co.” The John Carr & Sons mark began to be used in 1861, whereas the John Carr & Co. mark is first found around 1850.[23] Whether Carr exported his wares to the United States is currently unknown, but, in addition to making wares for the domestic market, he appears to have carried on a large export business with markets in the Middle East (including Iran), the Mediterranean, and Bombay, India.[24] Based on these marked examples, John Carr’s pottery might have produced Historic Deerfield’s plate as well.[25]

Sugar is decidedly anti-slavery in its outlook, and seems to celebrate emancipation by drawing readers’ attention to the “happy” life of the newly emancipated in the British West Indies—presumably those living in Jamaica—and by pointing to their changed condition of life. At the outset of the book the author notes how these individuals “used to be slaves, and were hardly treated, but they are now all free, and work for their masters at fair wages. They are now better used, and are taught in schools, and are as happy as hard working men can be.”[26] This positive view is also reflected in several of the book’s engravings. In these scenes, Black laborers—including the ones depicted on this plate—work without physical strain or duress and appear content. For example, the book’s second engraving, which immediately precedes the title page, depicts two Black women and two Black children seated on the ground in front of two wooden barrels. Their postures are relaxed, and three of the four sitters appear to be smiling. The uncritical reader is left with the impression that life has improved for the formerly enslaved population, shown to be comfortable and satisfied with their new lives. Indeed, the book’s language and imagery, as the title suggests, seems to offer readers a “pleasing account” of Black life in post-emancipation Jamaica. A nineteenth-century reader of the book or owner of this plate similarly might have taken comfort in the notion that emancipation had done much to improve the lives of the formerly enslaved.

While painting a “pleasing” picture of Black life in post-emancipation Jamaica, the book as a whole provides very little evidence that much had changed for the formerly enslaved population of the island. The scene on this plate, for an example, is virtually indistinguishable from (or could be easily confused with) other scenes of plantation life before emancipation. As the engravings in the book demonstrate, all of the labor-intensive tasks involved with making sugar—such as harvesting the cane and running it through the cane mill—continued to be done by members of the Black community. Since all of those tasks are accomplished in the early stages of sugar production, nearly all of the engravings in the first half of the book depict Black laborers. The Black laborers are also drawn in a very similar manner, with round heads, short hair, and obscured facial details, which, when compared with the book’s more detailed and varied portrayals of White people, detracts from their individuality as human beings.[27] It is only when the raw sugar leaves the West Indies and travels to Europe to be refined that White laborers enter the picture (see fig. 7). Accordingly, all of the laborers depicted in the engravings in the second half of the book are White.[28] The language employed in the book, in fact, attempts to rationalize or justify the racially divided labor force. As the author explains, “The negroes only are employed in all the hard work, for white men could not do it, not being used to hot climates. The negro labourers are black men from Africa, which is a very hot country....”[29] A nineteenth-century owner of a plate like this might have perceived the scene as simply representing the racial status quo, where Black workers carried out tasks that White laborers purportedly could not accomplish.[30] Overall, the book’s engravings and language suggest that a strict racial divide persisted in the actual labor force involved in the sugar-making process, revealing that emancipation and pro-emancipation literature did little to change or challenge the racial biases and stereotypes of the White population.

The historical record also supports the book’s visual and textual evidence. Indeed, despite the impression that Sugar might convey, post-emancipation life in Jamaica was not easy for the formerly enslaved. Although the book states that free workers received fair wages, low wages were a reality for some as well as a common complaint among the laboring poor of Jamaica in the decades following emancipation.[31] Additionally, as many authors have observed, emancipation did not mean equality:

While the lives of some black people improved after emancipation, freedom did not result in the transformation that had been expected. The gross inequity between the lives of the poor and the elite barely changed; unemployment was rife, and basic facilities such as medical care, which had sometimes been available on the plantations, were virtually nonexistent. The Jamaica Assembly, still dominated by planters, enacted harsh legislation that curtailed many aspects of life for the poor.[32]

Many White West Indians continued to hold onto ideas of White superiority, and adopted the mindset that the formerly enslaved needed to be “civilized” (i.e., adopt White religious and cultural traditions) in order to be good and productive citizens in British society.[33] Those realities support Hoiem’s argument “that production stories” like Sugar “reveal surprising details about technical processes for making things, but conceal the human cost of production” and the experiences of laborers.[34] With its long technical explanations of the methods used in cultivating and refining sugar, Sugar ignores the human aspect of the production story.[35] The book’s text and engravings, including the one printed on this plate, present a very sanitized version of plantation life in Jamaica that hide the true experiences of the formerly enslaved.

In this light, the plate assumed entirely new meaning and significance. While the plate may very well have been understood to communicate an anti-slavery message, it also became symbolic of a society in a state of social and ideological transition—from a society in which slavery was legal to one in which it was illegal. On the one hand, while serious legal changes had been enacted with the end of slavery in the British West Indies on August 1, 1838, the experiences of the formerly enslaved and individuals’ perceptions regarding race had changed very little in the ensuing decades (fig. 8). Freedom codified in law did not automatically translate into conditions of freedom or equality in reality. Willard’s fervent expectation that emancipation would confer the status of “human being” upon the formerly enslaved was not borne out in the eyes of society. Racial equality proved to be an elusive goal in Jamaica in the years following emancipation, foreshadowing in many respects the discrimination Blacks would continue to experience in the United States following their emancipation in 1865. The seemingly simple scene on this plate helps to document this complex and troubling reality, and illustrates that slavery’s legacy in the British West Indies persisted long after emancipation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author thanks Amanda E. Lange and Barbara A. Mathews for their generous help and assistance preparing this article

According to Merriam-Webster’s Geographical Dictionary, 3rd ed. (Springfield, Mass.: Merriam-Webster, 2001), the “West Indies” comprise the “islands, enclosing the Caribbean Sea, lying bet. [between] SE [south eastern] North America and N [northern] South America.”

Epaphras Hoyt, “Sketch-book No. 11” (1838, pp. 63–64). Epaphras Hoyt Sketch-book Collection, Historic Deerfield Library, Deerfield, Mass.

Mary Willard, ed., The Life of Rev. Samuel Willard, D.D., A.A.S. of Deerfield Mass. (Boston: Geo. H. Ellis, 1892), p. 181.

Speaking of children’s ceramics, Noël Riley writes, “While it would be reasonable to suggest that plates with moulded alphabet borders, transfer prints from children’s book illustrations or mugs and plates with individual names inscribed on them were made especially for children, many more may have been aimed at a wider market that embraced both children and adults.” See Noël Riley, Gifts for Good Children: The History of Children’s China, Part I, 1790–1890 (Ilminster, Somerset, Eng.: Richard Dennis, 1991), p. 8

Sam Margolin, “‘And Freedom to the Slave’: Antislavery Ceramics, 1787–1865,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), pp. 88–89.

Examples can be found in the collections of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (1998-37), the Chipstone Foundation (1999.22.a–b), the National Museums Liverpool (MMM.1994.111), and the British Museum (2002,0904.1).

Daniel Sousa, “Anti-Slavery Ceramics at Historic Deerfield,” Magazine of the Decorative Arts Trust 7, no. 1 (Summer 2020): p. 14.

Linda Gail France, “Sugar Manufacturing in the West Indies: A Study of Innovation and Variation” (master’s thesis, The College of William and Mary, 1984), pp. 40–41, 62–63.

Amelia Opie, The Black Man’s Lament: Or, How to Make Sugar (London: Printed for Harvey and Darton, Gracechurch-Street, 1826), p. 17.

Two examples include a ca. 1840 English whiteware child’s mug depicting European slavers capturing Africans in their native homeland, and a ca. 1850 English porcelain mug inscribed “Health to the Sick / Honour to the Brave / Success to the Lover / And Freedom to the Slave.” See Margolin, “‘And Freedom to the Slave,’” pp. 86–87, figs. 12 and 17.

“Constitution and Objects of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society,” British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Reporter 1, no. 1 (January 15, 1840): 1.

Ibid.

One American, David Lee Child (1794–1874), husband of Lydia Maria Child (1802–1880), worked to boycott sugar produced by enslaved persons by establishing a farm in Northampton, Massachusetts, in the late 1830s to grow beets for the production of beet sugar. See Carol Faulkner, “The Root of the Evil: Free Produce and Racial Antislavery, 1820–1860,” Journal of the Early Republic 27, no. 3 (2007): 388–89; and David Lee Child, The Culture of the Beet, and Manufacture of Beet Sugar (Boston: Weeks, Jordan, and Co.; Northampton, Mass.: J. H. Butler, 1840), pp. 3–4.

T. B. Thorpe, “Sugar and the Sugar Region of Louisiana,” Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 7, no. 42 (November 1853): 746–67.

Solomon Northup, Twelve Years a Slave (Auburn, N.Y.: Derby and Miller, 1853), p. 211. See also Khalil Gibran Muhammad, “The Barbaric History of Sugar in America,” New York Times Magazine, August 18, 2019.

Riley, Gifts for Good Children, pp. 7–9.

J.L.S., Sugar: How It Grows, and How It Is Made: A Pleasing Account for Young People (London: Darton and Clark, ca. 1845).

Elizabeth Massa Hoiem, “The Progress of Sugar: Consumption as Complicity in Children’s Books about Slavery and Manufacturing, 1790–2015,” Children’s Literature in Education 52 (2021): 163. John Maw Darton (1809–1881) and Samuel Clark (1810–1875) formed their publishing partnership in 1836. John was the son of William Darton Jr. (1781–1854) and the grandson of William Darton Sr. (1755–1819), both of whom worked as publishers and published several anti-slavery books for children, including William Cowper’s The Negro’s Complaint: A Poem. To Which Is Added, Pity for Poor Africans (1826). See Linda David, “Children’s Books Published by William Darton and His Sons: A Catalogue of an Exhibition at the Lilly Library, Indiana University, April–June, 1992,” Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington. https://collections.libraries.indiana.edu/lilly/exhibitions_legacy/etexts/darton /index.shtml.

Hoiem, “Progress of Sugar,” pp. 162–63, 166.

Catalogue of the Mercantile Library of Baltimore 1851 (Baltimore: John W. Woods, Printer, 1851), p. 105, 236. The catalog lists the book as “Sugar, how it Grows, and how it is Made.”

For “Harvest,” see Transferware Collectors Club Database of Patterns and Sources, Pattern Number: 16524, https://www.transferwarecollectorsclub.org/members/database. For “Open Pan Boiling,” see Kinghams Auctioneers, Moreton-in-Marsh, Gloucestershire, England, May 3, 2019, lot 1041.

Email from Martyn Edgell to author, June 9, 2022. Two different plates with the “Cane Mill” scene and molded “daisy” borders sold at auction in 2021. One sold at Hansons Auctioneers, Bishton Hall, Staffordshire, England, April 9, 2021, lot 178, and the other at The Canterbury Auction Galleries, Canterbury, Kent, England, April 12, 2021, lot 1329.

“John Carr (& Co) (& Son),” A–Z of Stoke-on-Trent Potters, http://www.thepotteries. org/allpotters/217a.htm.

Jaap Otte and Willem Floor, “English Ceramics in Iran, 1810–1910,” Northern Ceramic Society Journal 36 (2020): 110.

For additional information on John Carr’s pottery, see R. C. Bell, Tyneside Pottery (London: Studio Vista, 1971), pp. 133–34, 139.

J.L.S., Sugar, p. 6.

The portrayal of persons of color in this manner was common not only among pro-slavery advocates, but abolitionists as well. See Hoiem, “Progress of Sugar,” pp. 170–71; Kenneth DiMaggio, “Uncle Tom’s Ceramics: How a Popular Antislavery Novel Became Popular Postslavery Knick-Knacks,” International Journal of the Image 9, no. 1 (2018): 1–10; Margolin, “‘And Freedom to the Slave,’” p. 106.

This division of labor is indistinguishable from what persisted prior to emancipation. Referring to products produced by enslaved persons, Hoiem writes, “Commodities eaten or worn on the body, like sugar, cotton, and diamonds, began with enslaved persons working in one part of the globe, before raw materials were shipped to manufactories in other countries, where free workers refined, spun, packaged, and sold the products.” See Hoiem, “Progress of Sugar,” p. 167.

J.L.S., Sugar, p. 6.

Hoiem argues that some production stories encourage children to “accept the status quo [relating especially to labor conditions] in exchange for material plenty.” See Hoiem, “Progress of Sugar,” p. 169.

Gad Heuman, “Victorian Jamaica: The View from the Colonial Office,” in Victorian Jamaica, edited by Tim Barringer and Wayne Modest (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2018), p. 150; Tim Barringer, “Land, Labor, Landscape: Views of the Plantation in Victorian Jamaica,” in Victorian Jamaica, pp. 304–5.

Barringer and Modest, introduction to Victorian Jamaica, p. 9.

Ibid., p. 5.

Hoiem, “Progress of Sugar,” p. 162.

As Hoiem ultimately argues, this is a common theme found in production stories. See Hoiem, “Progress of Sugar,” pp. 162–65.