George Washington funeral medal, Jacob Perkins, Newburyport, Massachusetts, 1800. Gold. D. 1 3/16". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Sierra Medellin.) The medal features a shorthand biography of Washington to be contemplated by the wearer, much like Christian devotional medals.

Reverse of the medal illustrated in fig. 1.

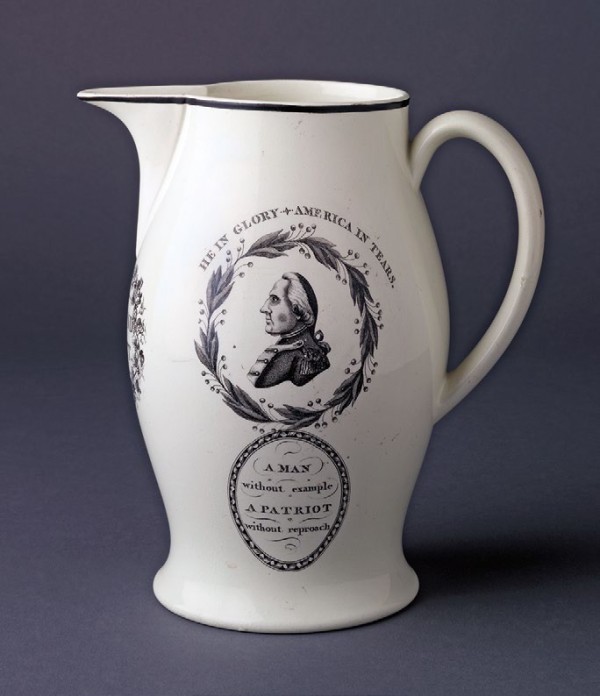

Jug, probably made at the Herculaneum Pottery, Liverpool, England, 1800. Creamware. H. 9 1/4". (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum; photo, Laszlo Bodo.)

Opposite side of the jug illustrated in fig. 3.

Front of the jug illustrated in fig. 3.

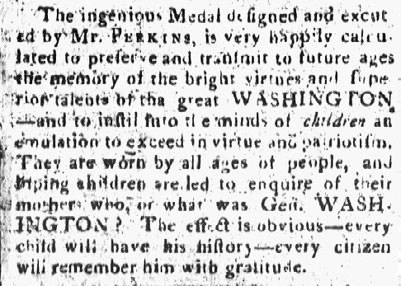

Description of the Perkins Washington funeral medal, published in the Newburyport Herald and Country Gazette, January 7, 1800. (Courtesy,

America’s Historical Newspapers.)

ON DECEMBER 14, 1799, George Washington died at Mount Vernon. The news traveled quickly throughout the United States, casting a fledgling nation into a state of mourning. With his death, Washington transcended his own humanity to become an icon, a symbol around which Americans could coalesce in their quest to form a national identity. Days after his death, local governments and fraternal organizations in nearly every American city and town began planning mock funerals.[1] These funerals offered orators and entrepreneurs an opportunity to memorialize Washington and to summarize the noble aspects of his life. The inventor and artisan Jacob Perkins designed a memorial medal to be “worn by all ages of people” that was first documented at the funeral procession in his hometown of Newburyport, Massachusetts, and later sold across the Northeast (figs. 1, 2).[2] New evidence suggests that Newburyport ship captain and merchant Edmund Swett commissioned Liverpool potters to copy Perkins’s design onto transfer-printed creamware jugs made specifically to commemorate the local funeral procession (figs. 3–5).

The Perkins funeral medal, pierced by the maker to hold a ribbon, first appeared on the necks of Newburyport’s citizens at the funeral procession held on January 2, 1800, merely seven days after news of Washington’s death had reached nearby Boston.[3] In that brief time, Perkins designed a medal of complex iconography, engraved its dies, and began striking it. Having apprenticed to a goldsmith, invented a machine for making nails, and worked on the Massachusetts state coinage, the 39-year old inventor was one of the few Americans capable of such a technical feat.[4] Perkins first advertised the medals for sale on January 6.[5] The speed with which he completed the medal was extraordinary; in contrast, one of the earliest mourning prints, America Lamenting Her Loss at the Tomb of General Washington, was issued in Philadelphia on January 20, more than three weeks after Perkins had begun striking his medal.[6]

The obverse of the medal features a bust of Washington in profile, derived from Joseph Wright’s popular 1790 portrait.[7] A laurel wreath and the inscription “HE IS IN GLORY, THE WORLD IN TEARS” surround his bust. On the reverse, Perkins distilled Washington’s biography into the elements that made him worthy of emulation in the eyes of many Americans. Encircling a funerary urn engraved with the initials “GW” are two inscriptions.[8] The outer reads: “B[ORN]. F[EBRUARY]. 11. 1732. G[ENERAL]. A[MERICAN] ARM[IES]. [17]75. “R[ESIGNED]. [17]83. P[RESIDENT] U.S.A. [17]89.” [9]The inner reads: “R[ESIGNED]. [17]96. G[ENERAL]. ARM[IES]. U.S. [17]98. OB. D[ECEMBER]. 14. 1799.” By featuring the dates Washington had resigned his military commission and left the presidency, Perkins reminded the medal wearers that Washington demonstrated leadership by both taking command and then returning power to civilian authority.[10] The Newburyport Herald described the medal’s purpose: “The effect [of the medal] is obvious—every child will have his history—every citizen will remember him with gratitude” (fig. 6).[11]

The medals were advertised for sale in Boston, Newburyport, Worcester, and Providence.[12] Edmund Swett likely took one of them to England, where it provided the design inspiration for a number of transfer-printed creamware jugs made in Liverpool, probably at the Herculaneum Pottery.[13] Founded in 1786, Herculaneum was one of the largest potteries in Liverpool, and a significant percentage of its production was made for export, especially to the United States.[14]

In nearly the same manner as the Perkins medal, one side of the jug features Washington’s bust encircled by laurel. The maker slightly shortened the phrase on the medal to “HE IN GLORY, AMERICA IN TEARS.” The other side features the reverse of the medal, with the urn. Although Perkins abbreviated his short history of Washington’s life on the medal, the engraver took full advantage of the space available on the ceramic body and spelled out each word, likely at the behest of the patron who understood the abbreviations.

Below the bust portrait is a cartouche with an inscription not seen on the medal, strengthening the ties between these jugs and Newburyport. The cartouche features the phrase “A MAN without example, A PATRIOT without reproach.” That phrase is taken directly from the published version of Thomas Paine’s eulogy delivered for Washington at the Newburyport Presbyterian meetinghouse, where the medals first appeared.[15]

While it is often difficult to determine the initial commissioner of specific designs on creamware, in this case a confluence of evidence points to Edmund Swett. At least eight jugs with this decoration are known, some 8 1/2" tall and others 10 1/4" tall. Two of the jugs were made for Swett, and personalized with his name hand-painted in a cartouche of wheat, hops, and grapevines beneath the spout. Unlike most Liverpool products, they have very little variation in design.[16]

Edmund Swett is almost certainly the man of the same name born on June 19, 1743, in the town of Newbury, four miles south of Newburyport. A mariner, shipowner, and merchant, he likely was present at the town’s funeral procession. After that event, Swett’s son Samuel sailed to Liverpool aboard the Industry, probably carrying with him one of his father’s funeral medals along with the published version of Thomas Paine’s eulogy. We can assume he left Newburyport in mid- to late January, as Billings’s Liverpool Advertiser reported his presence in Liverpool by March 17.[17] Samuel Swett arrived in Boston on June 22 after a 57-day journey, presumably bringing with him the commemorative jugs emblazoned with his father’s name as a gift and a few additional examples for sale, suggesting all the jugs were part of a single order.[18]

The Herculaneum Pottery likely made a single batch of the Newburyport jugs and then sold the examples not purchased by Swett to other Americans. One jug found its way to Alexandria, Virginia, where it was excavated from a site at 416-418 King Street. The site was owned by tanner Robert William Kirk until 1804, and then by stable and blacksmith shop owner Jacob Fortney.[19]

The creamware commemorative jugs and the sentiments expressed on them were universally appealing to an American audience, whose devotion to George Washington gave them value both within and without their New-buryport context. Positioning them in the context of the Perkins medals and Newburyport commerce illuminates both their creation and the dissemination of their imagery to a larger market.

George Washington was interred in the family vault at Mount Vernon, Virginia, on December 18, 1799.

Newburyport Herald, January 7, 1800, p. 3.

New-Hampshire Sentinel, January 25, 1800, p. 1. The newspaper contains an account of Newburyport’s funeral procession first published on January 3. The funeral procession at which the medals debuted was one of the first. The townspeople assembled in the market square at 10 a.m. and processed to the Presbyterian meetinghouse in a prescribed order: the artillery company and free masons led the way followed by dignitaries, clergy, the military, the choir, and the band. The citizenry followed “four abreast.” The men and women wore mourning badges recommended for the occasion, and most “added the elegant medal executed by Mr. Perkins.” When the citizens arrived, they found the sanctuary “judiciously dressed in mourning for the occasion,” likely black cloth draped on the pulpit, galleries, and chandelier. Ministers offered prayers, and the Reverend Thomas Paine delivered the eulogy in which he pronounced George Washington “a man without example, a patriot without reproach.” Thomas [Robert Treat] Paine, An Eulogy on the Life of General George Washington (Newburyport, Mass.: Printed by Edmund M. Blunt, 1800), p. 20. The large choir sang several hymns from Isaac Watt’s Lyric Poems, specially adapted to the occasion, and then the citizens exited the sanctuary. For the rest of the day, ships in the port displayed flags at half-mast, and businesses remained closed.

Greville Bathe and Dorothy Bathe, Jacob Perkins: His Inventions, His Times, & His Contemporaries (Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1943), pp. 1–33.

Russell’s Gazette, January 6, 1800, p. 3. Perkins indicated that the medals could be purchased through him in Newburyport or from the Boston goldsmith Ebenezer Moulton. The medals were worn at the Boston funeral procession on January 9, 1800, and the Boston Grand Lodge of Massachusetts procession on February 11, 1800, two of the largest in the country.

Wendy C. Wick, George Washington, an American Icon: The Eighteenth-Century Graphic Portraits (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, National Portrait Gallery, 1982), pp. 138–41. James Akin and William Harrison Jr. issued the print in Philadelphia on January 20, 1800.

Perkins borrowed his adaptation of the Wright profile from a one-cent coin commissioned in 1791 by the Philadelphia retailers John and Thomas Ketland from the Birmingham diesinkers John and Obadiah Westwood. The Ketland firm commissioned the coins in hopes of receiving a federal contract to mint United States coinage. Neil Musante, Medallic Washington: A Catalog of Struck, Cast and Manufactured Coins, Tokens and Medals Issued in Commemoration of George Washington, 1777–1890, 2 vols. (Boston and London: Spink, 2016), 1:65–66.

Two variations of the medal reverse exist: one with an urn and another with a skull and crossbones. Most medallic literature suggests that Perkins created the skull and crossbones reverse for the Boston Masonic funeral procession, though no contemporary evidence exists for that assertion.

Perkins combined George Washington’s date of birth in the Julian calendar (February 11, 1732) with that in the Gregorian calendar (February 22, 1732).

The most complete account of the medals and their variations is found in Musante, Medallic Washington, 1:131–41. Perkins offered the medal in gold, silver, and white metal; judging by the number of examples that survive and the variations between them, they proved popular.

Newburyport Herald, January 7, 1800, p. 3.

Massachusetts Spy, February 5, 1800, p. 3, and Providence Journal, and Town and Country Advertiser, January 29, 1800, p. 3.

The best account of these jugs appears in S. Robert Teitelman, Patricia A. Halfpenny, and Ronald W. Fuchs II, Success to America: Creamware for the American Market (Woodbridge, Suffolk: Antique Collectors Club, 2010), pp. 82–83.

Teitelman, Halfpenny, and Fuchs, Success to America, pp. 40–57; Peter Hyland, The Herculaneum Pottery: Liverpool’s Forgotten Glory (Liverpool, Eng.: Liverpool University Press, 2005), pp. 170–72.

Thomas [Robert Treat] Paine, An Eulogy on the Life of General George Washington (Newburyport, Mass.: Printed by Edmund M. Blunt, 1800), p. 20. The cartouche featuring Thomas Paine’s tribute to Washington appears on two other commemorative Washington jugs in the Winterthur Museum (2007.31.11 and 2007.31.13). One is marked by the Herculaneum Pottery (2007.31.13), attributing all three jugs to that manufactory. Both of the Winterthur examples feature Washington mourning scenes with obelisks. The cartouche design likely first appeared on the Newburyport jugs.

The jugs were made in two different sizes: 8 1/2" and 10 1/4". The two inscribed with the name Edmund Swett are in the collections of the Mattatuck Museum and the Winterthur Museum (2009.0023.003). On those examples, the decorator placed the Thomas Paine inscription below the bust and the name under the spout. On larger jugs without a name, the decorator added an additional floral border around the bust. Intact examples without personalization are in the collections of the Reeves Museum of Ceramics at Washington and Lee University (2013.26.1), the National Museum of American History—Smithsonian Institution (CE.63.126), the Delaware Historical Society (1958.004.007), George Washington’s Mount Vernon (M-5837), and Harvard University.

As reported in Gazette of the United States, May 21, 1800, p. 3. “S. Swett” is recorded as the captain of the Industry. He almost certainly is Samuel Swett (1772–1819), son of Edmund and Hannah Swett.

Massachusetts Mercury, June 24, 1800, p. 2.

Barbara H. Magid, “Commemorative Wares in George Washington’s Hometown,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2006), pp. 2–39