George and Martha Washington’s surtout arranged on a table with the mirrored silver plateau and biscuit porcelain figures Venus et deux amours and La Peinture. The table is arranged with the Sèvres dinner service the couple used during the presidency. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Plateau, France, ca. 1789. Silvered brass, mirrored glass, unidentified wood. H. 2 7/8", W. 17 3/8", L. 24". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Apollon instruisant les bergers, Charles Gabriel Sauvage, called Lemire (1741–1827), Dihl et Guérhard, Paris, France, 1803. Hard-paste biscuit porcelain. H. 24", W. 18 3/4", D. 14 1/8". (Courtesy, Royal Collection Trust/ © His Majesty King Charles III 2024.) François Benois purchased this example on behalf of George IV on August 4, 1803, along with a large quantity of other figures. George Washington’s figural group was likely identical to this example, though the president’s probably did not have a base.

Venus et deux amours, Charles Gabriel Sauvage, called Lemire (1741–1827), Manufacture du duc d’Angoulême, Paris, France, 1790. Hardpaste biscuit porcelain. H. 15 1/4", W. 12 7/8”, D. 7". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

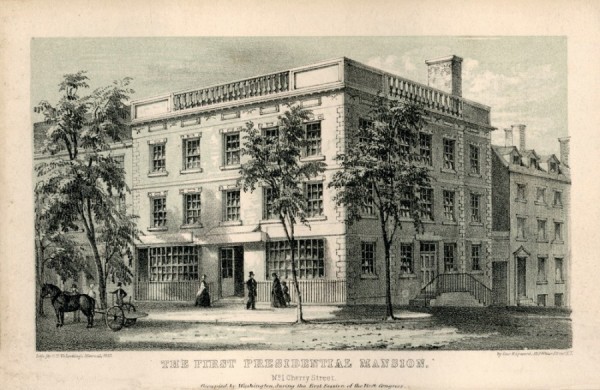

G. Hayward, The First Presidential Mansion, No. 1 Cherry Street; New York, 1853. Lithograph published in Valentine’s Manual [Manual of the Corporation of the City of New York, edited by D. T. Valentine]. (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.)

James Sharples (ca. 1751–1811), Gouverneur Morris (1752–1816), 1810. Pastel on paper. 9" x 7 5/16“. (Courtesy, Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery.)

Flora and Minerva, unknown maker, possibly Niderviller porcelain manufactory, France, ca. 1790. Hard-paste biscuit porcelain. Flora (left): H. 6”, D. 1Q 13/16". Minerva (right): H. 7", D. 1Q 13/16". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

La Peinture, Charles Gabriel Sauvage, called Lemire (1741–1827), Manufacture du duc d’Angoulême, Paris, France, 1790. Hard-paste biscuit porcelain. H. 11 1/4", W. 5", D. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, Stephen L. Zabriskie, of Aurora, N.Y.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

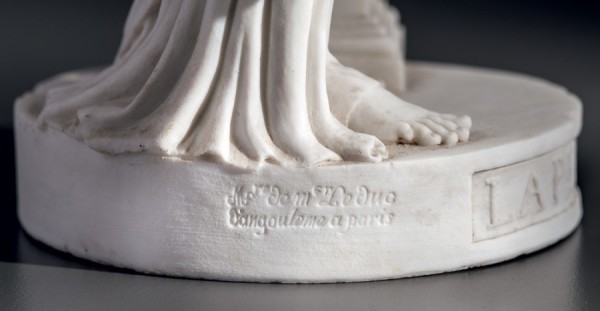

Mark on the base of the figure illustrated in figure 8.

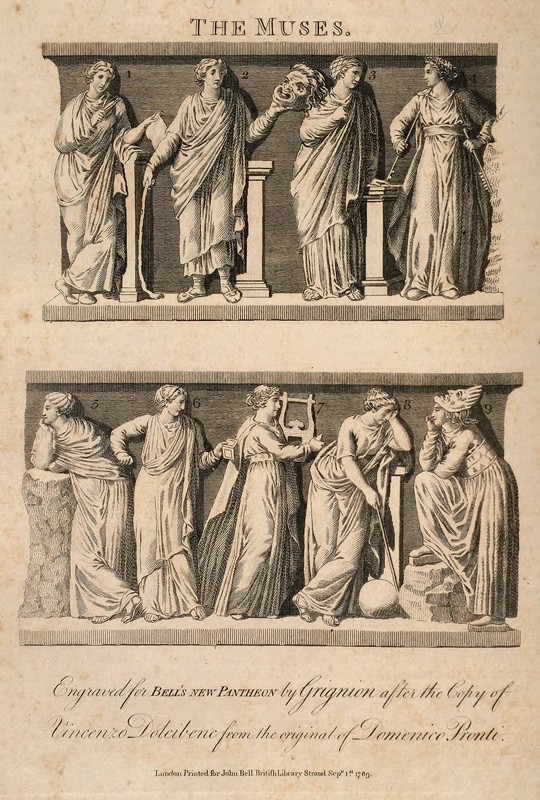

The Muses. Engraved for Bell’s New Pantheon by Grignion after the Copy of Vincenzo Dolcibinc from the original of Dominico Pronti. Engraving in Bell’s New Pantheon, or, Historical Dictionary of the Gods, Demi Gods, Heroes and Fabulous Personages of Antiquity (Courtesy, London: John Bell, 1790) (Hathi Trust.)

New Room, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

New Room, Mount Vernon, Mount Vernon, Virginia. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) George Washington’s figural groups are listed on the sideboards in this room in George Washington’s probate inventory, where they were likely covered by the glass domes purchased with the surtout to protect the larger figural groups. Several of the twelve figures of the “Arts and Sciences” likely rested on the sideboard as well.

Mantelpiece, attributed to Sir Henry Cheere (1703–1781), London, England, ca. 1770. Marble. H. 67 3/4”, W. 82 5/8“. (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Many of the individual figures of the “Arts and Sciences” likely occupied this mantelpiece between the Worcester Vases.

Sarah Miriam Peale (1800–1885), after Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828), Elizabeth Parke Custis (1776–1831), 1836. Oil on canvas. 28 1/2" x 24 1/8". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association.)

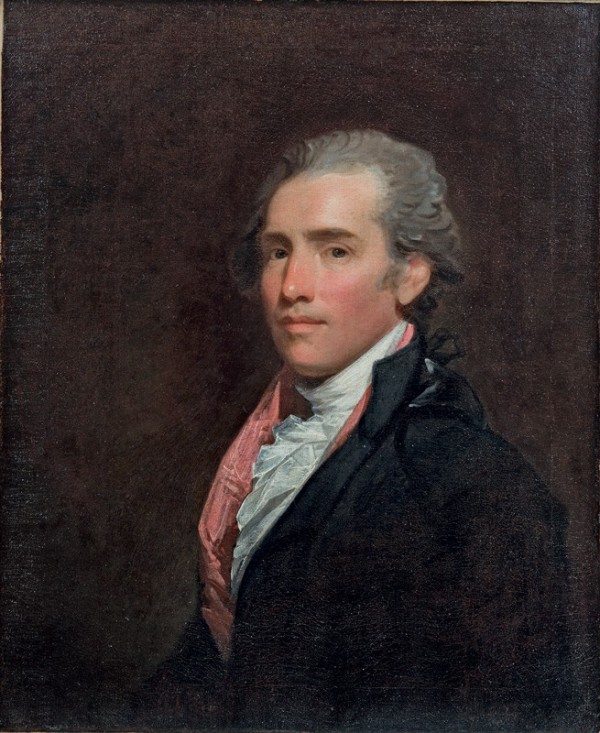

Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828), Thomas Law (1756–1834), ca. 1796. Oil on canvas. 29" x 24". (Courtesy, Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

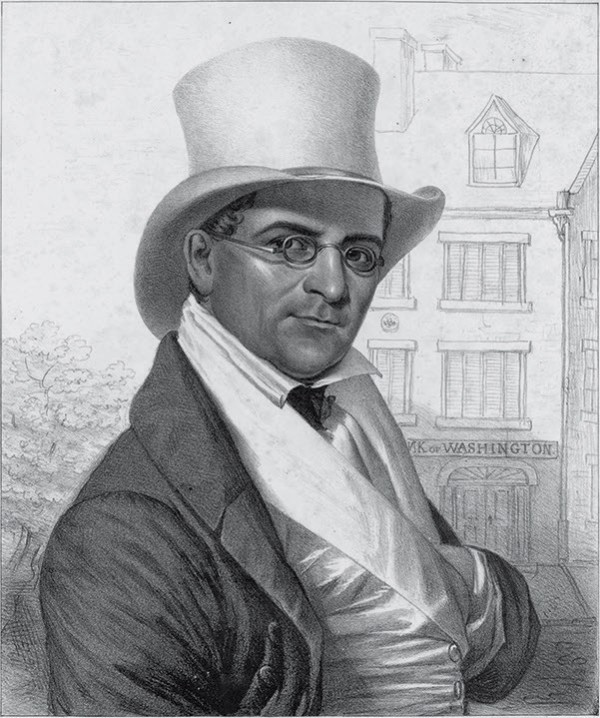

Charles Fenderich (1805–1889), after Samuel M. Charles, William Costin. A tribute to worth by his friends. Lithograph, 16 3/8" x 13 1/4" published by P. S. Duval’s Lithographic Press, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1842. (Courtesy, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.)

Adam Snyder, Windsor arm chair, Philadelphia, ca. 1800. Unidentified painted wood. H. 33 1/2", W. 19", D. 15". (Courtesy, Stephen L. Zabriskie, Aurora, N.Y.; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The brass plaque beneath the crest rail is inscribed “From Washington’s Library Mount Vernon.”

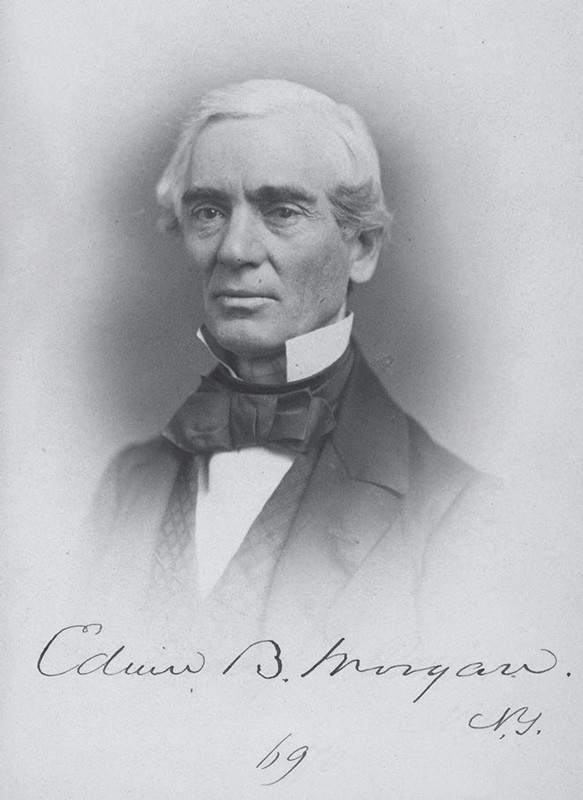

Congressman Edwin Barber Morgan, 1859. Photograph by Julian Vannerson published in McLees’ Gallery of Photographic Portraits of the Senators, Delegates, & Representatives of the ThirtyFifth Congress (Washington, D.C.: McLees and Beck, 1859) (Courtesy, Library of Congress.)

EVERY THURSDAY DURING the presidency, George (1732–1799) and Martha Washington’s (1731–1802) hired steward and enslaved waiters oversaw the creation of an elaborate stage set at the center of the dining table for that night’s meal (fig. 1). The Washingtons intended for the surtout de table to impress the rotating group of congressmen, diplomats, and dignitaries whom they invited to each official dinner. Recently ordered from Paris, the set consisted of a raised mirrored plateau, ten feet long and two feet wide, stretching the entire length of the table (fig. 2). Atop the plateau, these men arranged a delicate and expensive set of biscuit porcelain figures dressed in classical attire, giving the impression that the figures were in conversation with each other and with the guests. At the center of the surtout rested a large figural group titled Apollon instruisant les bergers (Apollo instructing the shepherds), while at either end stood a smaller group—Venus et deux amours (Venus and two amours, or cupids)— and another now lost figural group (figs. 3, 4). Two vases, purchased with the rest of the set, rested between the three large figural groups, while a set of twelve individual figures depicting the “Arts and Sciences” sat in a ring around the outside edge. Throughout the presidency, this stage set, with gleaming white figures harkening back to classical antiquity, delighted the Washingtons’ guests, creating an appropriate setting for George Washington to guide the course of the new republic with leaders gathered around his dining table.[1]

Acquired in 1790, the Washingtons’ French plateau and biscuit porcelain figures are some of the best-documented and most symbolically important objects the couple owned. Because of their expense and fragility, George Washington took particular interest in their care and movement, causing their various caretakers to write about the pieces as they were transported between Paris, New York, Philadelphia, and Mount Vernon. Although these pieces are well documented, until recently only two elements were known to survive: the mirrored plateau, and the figural group Venus et deux amours.[2] The histories of the remaining elements and their appearance remained a mystery until 2017, when one of the twelve figures of the “Arts and Sciences,” a figure titled La Peinture (Painting) was discovered in a private collection in Aurora, New York, along with a nineteenth-century note documenting its history.[3]

The emergence of this single figure and the reexamination of primary sources provide enough information to establish the titles of most of the figures in the original ensemble. This additional information provides the missing evidence necessary to decode the complex classical iconography of George Washington’s dining table. Additional research has also revealed that part of this group, the figures of the “Arts and Sciences,” first passed to Martha Washington’s eldest granddaughter Elizabeth “Eliza” Parke Custis (1776–1831), who in turn gave some of them to the prominent Black porter William Costin (1780–1842) and his wife, Philadelphia “Delphy” Judge Costin (ca. 1780–1831), who was formerly enslaved at Mount Vernon. Their daughter, Harriet Costin Fiske (1819–1881), then sold a single figure, Le Peinture, to Congressman Edwin B. Morgan (1806–1881) of New York, and it survives in his descendant’s possession today.[4]

This chain of ownership not only sheds light on the afterlife of these important pieces once they left Mount Vernon; it adds an important piece to the puzzle of William Costin’s relationship with the Custis family. Piecing together evidence from the nineteenth century and family histories, it appears likely that Costin was the son of John Parke “Jacky” Custis (1754– 1781), Martha Washington’s only son, and an enslaved woman named Ann or Nancy (dates unknown). The transfer of a valuable Washington object to Costin strengthens the case that Costin was, in fact, related to the Custis family. Eliza Parke Custis (1776–1831), Jacky’s eldest daughter with his wife Eleanor Calvert Custis (1758–1811), kept these key pieces in the family; William Costin was quite likely her half-brother, born into slavery and freed by Eliza and her then-husband in 1802. Costin’s daughter Harriet maintained her relationship with the Custises and, like her father, was well connected with the elites of the capital city despite the barriers of race. This single ceramic figure, then, is the silent carrier of an important hidden history that offers new insights into both the Washington/Custis family and race in the new nation.

Setting the Presidential Dining Table

Soon after George Washington was sworn in as president of the United States, he turned his attention to upgrading the furnishings provided by Congress for the Executive Residence (fig. 5). Although these furnishings were the best that could be assembled in short order, they did not live up to the vision George and Martha Washington had for the home of the nation’s first chief executive. George Washington held Thursday dinners as one of the key social events of the week, and he first began planning to equip the dining table in a manner that would convey both his and the country’s sophistication, importance, and aspirations. George and Martha Washington had seen plateaus ornamented with porcelains on the tables of the British and French ambassadors, his two primary international contacts, and also on the tables of Robert Morris (1734–1806) and William Bingham (1734–1804), two wealthy Philadelphians with significant international presence. The placement of a mirrored plateau, or small platform, onto a dining table in order to create a stage set for porcelains, flowers, and other decorations was a French innovation recently imported to the United States by the diplomatic classes and these merchants. George and Martha Washington must have viewed these ensembles as essential equipage for a diplomatic household at a point when the French taste had become standard in wealthy New York and Philadelphia households after having been introduced by American diplomats and merchants in the 1780s.[5]

After searching unsuccessfully for a plateau in Philadelphia, George Washington wrote to his friend, the wealthy New York merchant and politician Gouverneur Morris (1752–1816), who had recently moved to Paris on business (fig. 6). Washington requested that Morris find—in either London or Paris—“mirrors for a table, with neat and fashionable but not expensive ornaments for them” to furnish a table ten feet long. He suggested that Morris refer “to what you have seen on Mr. Robert Morris’s table for my ideas generally.”[6] Morris understood the weight of this commission and the importance of setting a proper table for both domestic and international diplomacy.[7] Many wealthy Americans relied upon friends and businessmen abroad to serve as proxy shoppers in the fashionable European centers of London and Paris. When practical, the Washingtons chose individuals who knew them well and could be relied upon to find objects that matched their taste.[8]

Upon receiving Washington’s request, Gouverneur Morris, accompanied by his mistress, Adélaïde-Emilie Filleul, comtesse de Flahaut (1761– 1836), first visited the Sèvres Royal Porcelain Manufactory on January 11, 1790. He found that the price for the surtout would be far too expensive and that it could not “be finished before October next,” halfway through Washington’s first term.[9] He then turned to the duc d’Angoulême’s porcelain manufactory, which he had previously visited out of curiosity and to become acquainted with its product in March 1789. He found that the head of the porcelain factory, Christophe Dihl (1752–1830), was “a German or Swiss and boasts much of his work.” After viewing Dihl’s exquisite offerings, Morris determined that his bragging was justified and that the product was irresistible. He exclaimed, “’Tis a Pity that some Vases of most exquisite Workmanship should be of brittle China Ware. In Spite of Reason a Person possessed of Money would I think be obliged to make some Purchases.”[10]

The Manufacture de monsieur le duc d’Angoulême was one of the more prominent of a group of porcelain manufacturers founded in Paris at the close of the eighteenth century in competition with Sèvres. The firm operated under the patronage of Louis-Antoine d’Artois (1775–1844), duc d’Angoulême (who became patron of the firm at the age of five), the nephew of Louis XVI. Christophe Dihl, a successful potter and modeler from Neustadt, founded the firm in collaboration with the wealthy businessman Antoine Guérhard (d. 1793) and his wife Louise-Françoise-Madeleine Croizé (1751–1831). The firm quickly became one of the more successful hard-paste porcelain manufactories in Paris, known for its exceptional modeling and ability to imitate stone in enamel on porcelain.[11] Gouverneur Morris recorded that he and his mistress “agree that the Porcelaine here is handsomer and cheaper than that of Séve [sic],” and he decided to purchase the figures for Washington there.[12]

Morris sent the service to Washington in New York on January 24, 1790, along with specific instructions on how it should be placed on the table and the appropriate manner of cleaning the figures.[13] Later that day, he penned a second letter to Washington defending his choices:

You will perhaps exclaim that I have not complied with your Directions as to the Oeconomy, but you will be of a different opinion when you see the Articles. I would have sent you a Number of pretty Trifles for very little prime Cost, but the Transportation and freight would have been more and you must have had an annual Supply, and your Table would have been in the Style of a petite Maitresse of this City, which most assuredly is not the Style you wish. Those now sent are of a noble Simplicity and as they have been fashionable above two thousand years, they stand a fair Chance to continue so during our Time . . . I think it of very great importance to fix the Taste of our Country properly, and I think your example will go very far in that Respect. It is therefore my Wish that every Thing about you should be substantially good and majestically plain; made to endure.[14]

The Founding Fathers looked to Greek philosophy and the form of the Roman Republic as models for their new government, and Morris chose the figures in the “antique,” or Greek and Roman, taste to evoke these ideals. Most elite Americans were imbued with these concepts from childhood, when they studied Greek and Latin as the basis of their classical educations. Although George Washington did not receive such an education, he read many of the classical texts in translation and was conversant in classical iconography. Throughout the eighteenth century, Europeans uncovered Roman ruins and statuary, inspiring artists, architects, and artisans to emulate these finds and leading many, including Morris, to see the classical taste as the only appropriate style for the leader of the new nation.[15]

George Washington appreciated Morris’s efforts, and he reported back that he found the figures and the plateau to be “very elegant” and “much admired.”[16] Congressman Theophilus Bradbury (1739–1803) saw them on display at a Christmas dinner at the Philadelphia executive residence in 1795. He wrote to his daughter Harriet and described the plateau in detail; it was apparently a type of decoration he had not previously seen, and it made an impression:

In the middle of the table was placed a piece of table furniture of wood gilded, or polished metal, raised only about an inch, with a silver rim round it like that round a tea board; in the centre was a pedestal of plaster of Paris with images upon it, and on each end figures, male and female, of the same. It was very elegant and used for ornament only.[17]

He found the various dishes of the meal arrayed around the table in the French manner.

The Figures

Susan Gray Detweiler made the first important attempt to reconstruct the appearance of the biscuit porcelain suite in her 1982 book George Washington’s Chinaware. She correctly identified the figural group Venus et deux amours (Venus and two amours) in the Mount Vernon collection as one of the two smaller figural groups and the now missing Apollon instruisant les bergers (Apollo instructing the shepherds) as the larger central group.[18] She also identified a pair of figures, Minerva and Flora, now in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, as two of the twelve figures of the “Arts and Sciences” (fig. 7). In the absence of the recently discovered figure, that supposition seemed entirely plausible, although the figures of Minerva and Flora are only six and a half inches tall and dwarfed in comparison with the fifteen-and-a-quarter-inch Venus et deux amours.[19] George and Martha Washington’s account books record the purchase of numerous additional biscuit porcelain figures to augment the table and to surprise guests continually. It is likely that these smaller figures were among those later purchases.[20]

The discovery of La Peinture and subsequent research have led to a comprehensive reassessment of the ensemble. This analysis has revealed the names of twelve of the fifteen individual figures used by Washington. This has, in turn, suggested that Gouverneur Morris had a carefully conceived and complex iconographic program in mind when he selected the figures that he did from the dozens of options at the Angoulême porcelain manufactory. The ensemble was not simply a random assemblage of classical Greek and Roman figures, as has been assumed in the past, but was instead a bold statement of Washington’s and Morris’s shared vision for the new nation, laid upon the table for guests to decipher and discuss.

Utilizing classical figures to convey a message on the dining table was not unique to Washington and Morris. In 1785 Thomas Jefferson (1743– 1826) sent to Abigail Adams (1797–1801) from Paris a plateau and three of the four classical figures (Minerva, Diana, and Apollo) she had requested for the dining table. When he could not find the fourth figure, he chose “a fine Mars,” which he deemed appropriate for the table of her husband John Adams (1735–1826), who then served as American minister in London. Jefferson wrote that those who saw the group might “look and learn that though Wisdom [Minerva] is our guide, and the Song [Apollo] and Chase [Diana] our supreme delight, yet we offer adoration to that tutelar [sic] god [Mars] also who rocked the cradle of our birth, who has accepted our infant offerings, and has shewn himself the patron of our rights and avenger of our wrongs.”[21] Thomas Jefferson and Abigail Adams together designed a classical iconography that conveyed their vision of the United States and the idea that the infant country may once again show its military might.

The narrative of George Washington’s porcelain figures consists of three groups that together suggest a single story with a political message. The first part is the central figure, which is also the largest, Apollon instruisant les bergers. The figural group consists of Apollo, the sun god, lying on a rock with his arm around a young man, a shepherd, whom he is instructing. Apollo was the god of herdsmen and shepherds as well as the protector of herds, flocks, and crops.[22] The group addresses the agricultural foundation of United States commerce and George Washington’s vision that one day the United States would “become a storehouse and granary for the world,” albeit one worked by enslaved labor (fig. 3).[23]

George Washington expressed this vision in a 1788 letter to the French military officer the marquis de Chastellux (1734–1788), who had served under him during the American Revolution:

It is time for the age of Knight-Errantry and Mad-heroism to be at an end. Your young military men, who want to reap the ha[r]vest of laurels, dont care (I suppose) how many seeds of war are sown: but for the sake of humanity it is devoutly to be wished that the manly employment of agriculture and the humanizing benefits of commerce would supersede the waste of war and the rage of conquest—that the swords might be turned into plough-shares, the spears into pruning hooks—and, as the Scripture expresses it, the nations learn war no more.[24]

The Apollo figure also references Washington as the American Cincinnatus. In the years after the American Revolution, contemporaries likened Washington to the fifth-century BCE Roman general Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, and Washington embraced the concept in both his writings and the decoration of Mount Vernon. Cincinnatus was appointed dictator when the Roman Republic was threatened by an outside tribe. He led the Roman army to victory, and then, rather than maintain power, he resigned and returned to his farm. In a society imbued with classical iconography, Cincinnatus was seen as the supreme example of civic virtue. George Washington’s use of farming motifs in his interiors and on the table reminded his guests that he gave up power to return to his farm.

The second part of the set includes two smaller figural groups: one features the Roman goddess Venus and is titled Venus et deux amours (fig. 4), while the other is lost, its identity unknown. The seemingly amorous nature of the Venus figure has distracted previous scholars from its iconographic meaning. In addition to her role as the goddess of love, Venus was also the mother of Rome. According to mythology, Venus gave birth to Aeneas, the hero of Troy who led the Trojan survivors after their defeat at the hands of the Greeks. After leaving Troy, Aeneas made his way to the mouth of the Tiber River, where he married Lavinia, daughter of the local King Latinus; all Romans purportedly descended from this marriage. Aeneas founded Alba Longa, the future home of Romulus and Remus, the founders of Rome.[25] By placing a figure of Venus on the president’s dining table, Morris suggests a connecting parallel between George Washington and the United States, and Venus and the Roman Republic.

The third iconographic group consisted of twelve figures of the “Arts and Sciences.” These included the Nine Muses and three related companions. In Morris’s composition, the Muses, followers of Apollo, represented his and Washington’s hopes for the future of the young nation when the arts and sciences might flourish—though both men understood that this was not the country’s present situation. During the American Revolution, John Adams succinctly described this hope in a letter from Paris to his wife, Abigail. After visiting Versailles, the Tuileries, and other French monuments—and viewing their art, architecture, and gardens—he declared: “It is not indeed the fine Arts, which our Country requires. The Usefull, the mechanic Arts, are those which We have occasion for in a young Country.”[26] Adams and his contemporaries believed that, if they and their sons worked to establish a prosperous society, they could prepare a country in which their grandchildren might earn the right, through the work of their forefathers, “to study Painting, Poetry, Musick, Architecture, Statuary, Tapestry and Porcelaine.”[27] George Washington’s dining table expressed this ideal in objects rather than words.

The discovery of the figure with “LA PEINTURE” impressed on the base—and subsequent research—has revealed more about the appearance of the twelve figures. La Peinture is classically attired, leaning against a plinth. Though the elements are now lost, she originally held a palette in her left hand and a paintbrush in her right (fig. 8).[28] Her base is impressed with the mark “Mf r de Mgr Le duc d’angouleme a paris” (fig. 9). She stands a commanding eleven and a quarter inches tall, placing her in scale with the larger figural groups. La Peinture provides the scale and the model for the remaining eleven that are no longer known to survive, while a list of the models owned by Christophe Dihl at his death and additional newly found documentary evidence reveal the probable appearance of the rest.

La Peinture appears on inventories taken at the time of Christophe Dihl’s death, which include both the names of the molds in Dihl’s possession and, on many occasions, the names of the sculptor who made them. The figures Apollon instruisant les bergers, Venus et deux amours, and La Peinture all appear on the inventories along with the name of their sculptor, Charles Gabriel Sauvage, known as Lemire (1741–1827). Lemire was a sculptor and modeler who had trained under the sculptor Paul Louis Cyfflé (1724–1806) at the Lunéville faience manufactory in the Duchy of Lorraine before moving to the Niderviller manufactory, where he became head of the factory and chief modeler and also where he founded a modelling and drawing school. While employed by Niderviller, Lemire sculpted a number of figures for the Angoulême factory including La Peinture and all of the Washington figures are among those he sculpted at that time. After the beginning of the French Revolution, Lemire moved permanently to the Angoulême firm, newly renamed Dihl et Guérhard; he served as its most prominent modeler for the rest of his career.[29]

The Washington set consisted of twelve female figures in classical attire holding attributes associated with each respective art or science. Nine of the twelve were the muses of ancient Greek mythology (fig. 10), a fact recounted by a visitor to the home of Eliza Custis Law who recorded seeing “a Set of the whole Nine Muses, done in the consummate Style of French Execution,” which were a gift from “her grandmother Mrs. Go. Washington.”[30] The Muses were the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, and Apollo was their leader. They were the source of inspiration for literature, the arts, and the sciences. Five of the nine muses are listed in the Dihl inventory as sculpted by Lemire; Euterpe (flutes and music), Melpomene (tragedy), Terpsichore (dance), Polyhymnia (hymns and sacred poetry), and Urania (astronomy). The four remaining muses—Calliope (epic poetry), Clio (history), Thalia (comedy and pastoral poetry), and Erato (love poetry and lyric poetry)—do not appear on the list of Dihl’s models, although they were almost certainly present in the Washington set.[31]

Painting, however, is not one of the nine muses, and George Washington owned twelve individual figures of the arts and sciences. Morris apparently extended the set of Muses to accommodate a longer dining table, but his choices remained within the theme. La Peinture, a classical female figure with her attributes, demonstrates that additional figures could closely resemble the Muses even though they were not technically members. The remaining two figures were likely also sculpted by Lemire, and given the subject matter, they were likely either La Poésie (Poetry), La Sculpture (Sculpture), or L’Architecture (Architecture).[32]

Mount Vernon

At the conclusion of the presidency, the Washingtons decided to sell the plateau and biscuit porcelain figures in Philadelphia rather than bring them to Mount Vernon. Although the suite had served the Washingtons well at official meals, they likely found the complete ensemble too formal for use in retirement. George Washington wrote to Clement Biddle (1740–1814), then acting as his Philadelphia agent, requesting that he sell the pieces. Washington included with his letter the original invoice for the porcelain and asked that Biddle get the best price he could, even though “they have not only been used, but the Porcelain in some of its nicest parts, has been injured.”[33] Because of an outbreak of yellow fever, Biddle delayed the sale until consumer moods improved, giving Washington time to reconsider the sale.[34] By January 1798, nine months after leaving Philadelphia, Washington decided that he might, in fact, have some use for them, and he countermanded his previous request. He asked that Biddle send to Mount Vernon all of the figures with the exception of the “large group (Apollon instruisant les bergers) and the two vases,” which he instructed should “be sold for what they might fetch.”[35]

Once the remaining figures and plateau arrived at Mount Vernon, the Washingtons likely never again used the service on the dining table.[36] They did use the porcelain figures, however, to decorate the New Room. The New Room served as a large dining room and a drawing room to display art; it was the final, and most elaborately decorated, space added to the mansion (fig. 11). The couple placed the two smaller figural groups with their glass covers on the sideboards flanking the venetian window, where they provided a focal point amid an array of knife cases (fig. 12). In George Washington’s probate inventory, the remaining “Images” appear in the same space, and they likely sat on the mantel between the Worcester vases and filled-out sideboards (fig. 13).[37] The classical porcelain figures complemented the neoclassical stucco work and plaster decoration of the room, with the cool white of the biscuit porcelain reflecting the lime white of the plaster. The use of the figures also evoked on a much smaller scale neoclassical English interiors such as the dining room at Lansdowne House, London, and the statuary hall at Holkham House, Norfolk, for which aristocratic collectors had brought back classical statues and amassed them in large rooms. By the time of Martha’s death two and a half years later, the large figural groups remained on the New Room sideboards, but the individual figures and plateau no longer appeared in the house. It seems most likely that Martha had already given the twelve figures of the “Arts and Sciences” and the mirrored plateau to her eldest granddaughter, Elizabeth “Eliza” Parke Custis, who was busy setting up her own household in the newly founded Federal City.[38]

Elizabeth “Eliza” Parke Custis

Eliza Parke Custis was the eldest of Martha Washington’s grandchildren, born in 1776 to Martha’s son from her first marriage, John “Jacky” Parke Custis, and his wife, Eleanor Calvert Custis (1757/58–1811) (fig. 14). The Custises had three more surviving children: Martha (Patty) (1777–1854), Eleanor (Nelly) (1779–1852), and George Washington (Wash) Parke Custis (1781–1857). Their final child, Wash Custis, was only six months old when Jacky Custis died of camp fever contracted at Yorktown in 1781, and the Washingtons adopted the two youngest children.[39]

It was likely on a visit to the Washingtons in Philadelphia that Eliza met the man she would marry, Thomas Law (1756–1834) (fig. 15). Twenty years her senior, Law had spent two decades in India building his fortune and moved to the United States with plans to further it. Law quickly began investing in lots in the soon-to-be capital city, the District of Columbia, and given George Washington’s role in planning the city, the marriage would considerably advance Law’s interests. In February 1796 the couple announced their engagement; they married the following month in Virginia and moved into a large home along the Potomac River in the District of Columbia.[40]

However, neither their stay in the new house nor the marriage lasted long. The couple moved frequently among various properties, most on New Jersey Avenue on Capitol Hill, in which Thomas Law had invested. In these new and elegant homes, they entertained the city’s elites and raised their first and only child, Eliza Law. It is not clear in which of these properties they were living when a visitor spotted the porcelain muses on their mantel in 1802. New York Congressman Samuel Latham Mitchill (1764–1831) reported to his wife in February of that year that the figures “stand on the Chimney Piece [sic], except Erato, who has had her Arm broken and is not fit to appear before Company.”[41]

Eliza’s peripatetic life continued when she separated from Thomas Law just over two years later. Other than four years spent in a home she purchased in Alexandria and named Mount Washington, she never had a permanent home. The porcelain figures were only a fraction of the large collection of Washington objects Eliza owned, many of which she purchased at an estate sale after Martha Washington’s death.[42] Eliza gave most of these pieces to her grandchildren with careful labels explaining their history, and succeeding generations preserved the objects and donated many of them to Mount Vernon in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Perhaps Eliza gave part of the set of porcelain figures to her grandchildren, but it appears she gave at least five of the pieces to someone else: her likely half-brother William Costin.

William Costin

William Costin was born in 1780 to an enslaved woman owned by the Custis family who went by Ann or Nancy (fig. 16).[43] There is considerable and suggestive evidence that Martha Washington’s son John Parke Custis was William Costin’s father. While the most commonly cited nineteenth-century report on Costin’s ancestry states that his father was from a “prominent family,” his daughter’s account identifies Jacky as the father, as did a descendant who communicated with Mount Vernon in the 1980s.[44]

Subsequent developments in Costin’s life demonstrate a close connection with the Custis family. Eliza Custis’s husband, Thomas Law, manumitted Ann/Nancy and all her children, including one who appears to be William Costin, and then later on William Costin’s wife, Philadelphia “Delphy” Judge Costin, and their young children. Costin stayed in touch with all four Custis grandchildren over the course of their lifetimes, and perhaps most telling, he gave all seven of his children the middle name Parke. There was a tradition going back several generations in the Custis family, tied to a clause in ancestor Daniel Parke’s early eighteenth-century will, of using Parke as a middle name.[45] Finally, Costin’s ownership of the Washington porcelain figures offers a physical tie to the Washington/Custis family. Eliza rarely gave Washington objects to people outside of her family; Costin’s ownership of them testifies to the strong and likely kinship relationship she shared with this formerly enslaved man.

Although the popular nineteenth-century account of William Costin’s life states that he was born free, manumission records suggest otherwise. In late July 1802, Thomas Law freed Nancy Holmes and a “Negro William now aged about twenty-two years.” This precisely aligns with Costin’s purported birth year of 1780, and the fact that the two were freed at the same time strongly suggests a relationship between them.[46] How Thomas and Eliza came to own Ann/Nancy and Costin is unclear; they were not among the forty-three people Eliza inherited from Mount Vernon after Martha Washington’s death in 1802, although Costin’s future wife, Delphy Judge, was. It is likely, then, that Costin and his mother were part of Eliza’s dowry when she married Thomas Law in 1796.[47]

The District of Columbia’s less restrictive laws and ample work opportunities made it home to a growing free Black population, where William Costin could build a secure and prosperous life. While in 1800 twenty-three percent of D.C.’s population was Black and just twenty percent of Blacks were free, by 1840 thirty percent of the city was Black and sixty-four percent of them were free.[48] The new capital was no egalitarian paradise for Black residents; they still could not vote, hold office, nor bear arms. However, until the city government passed curfews and additional restrictions on employment and residency in the 1820s and 1830s, free Black people could live better there than in many other places. They built enough wealth that tax records show them as similar financially to the city’s average white taxpayer.[49] While many spaces in the city were increasingly segregated, for many years Black residents could sit in the balconies of the U.S. Capitol to watch Congress at work, worship in churches with white congregants, and attend outdoor public events like inaugurations and parades.[50]

William Costin found considerable financial success in the growing capital district. In 1818 he was hired as a porter at the Bank of Washington and regularly entrusted with delivering large sums of money. It was a considerable promotion from his earlier work as a hack driver, carrying people and goods around the city. Rather than running individual errands by coach, he was now transporting cash; it was estimated that in his twenty-four years in the position, he handled millions of dollars.[51] Many African American men in D.C., both free and enslaved, worked as drivers of coaches and hacks; others were tradesmen, construction workers, cooks, or hairdressers. A small number were teachers, religious leaders, or doctors.[52] Costin’s position at the bank situated him occupationally in ranking closer to this higher echelon of professionals as opposed to common laborers.

Costin’s new position enabled him to become a property owner. In the same year he became porter, Costin leased part of a lot on A Street Southeast (between New Jersey Ave and 1st Street) in Capitol Hill for ninety-nine years from his employer at the bank, Daniel Carroll.[53] There his family took up residence in a two-story brick house. Just over a decade later, he purchased a lot across the street for $610 that also had a brick house (which was mortgaged to the Bank of Washington for $490 when Costin wrote his will in 1833).[54] The neighborhood was populated by minor tradesmen and government clerks, most of them white and some owning small numbers of enslaved people. Also on Capitol Square were a physician, a stonecutter, a grocer, the home of the doorkeeper of the Senate, a boarding house, and a Black hairdresser.[55] At some point Costin also purchased land over the hill from the Capitol, where he had two frame houses. By the 1840s he was one of the larger Black property owners in the nation’s capital.[56]

Costin had become what one of the city’s justices of the peace called the most “upright, honorable, and reputable man of colour . . . in the city.”[57] He served as an officer in multiple associations in the free Black community and fought for the rights of free Blacks after the District of Columbia imposed new racial restrictions. Refusing to comply with an 1821 law that required all free Black people to prove their freedom, have three white residents testify to their character, and post a twenty-dollar bond, Costin fought the law in court. His lawyer, almost certainly in consultation with Costin himself, argued that “The Constitution knows no distinction of color. . . . All who are not slaves are equally free [and] equally citizens of the United States.”[58] While the judge disagreed with these expansive claims, Costin ultimately prevailed because the judge said the law could not be applied to Black residents already residing in the city.[59] Costin also purchased and freed three enslaved people owned by Eliza’s brother, George Washington Parke Custis.[60] The surviving portrait print of him shows a man whom viewers could easily have identified as white, wearing fine clothing, a top hat, and small spectacles. He gazes seriously at the viewer with his right eyebrow slightly raised in scrutiny—or perhaps amusement.[61]

It was perhaps a combination of his respectability and family ties that made him a trusted, if subservient, friend of the prominent Custis family. He ran errands for the Custises, conveying family members and making deliveries in his carriage. While these are tasks that a servant might perform, the relationship was more complicated: he was wealthy enough that he also lent both Eliza and her sister Nelly small sums of money.[62] Nelly addressed a letter to him with “My friend Billy” and closed with “I hope you & your family are well, I will ever be your friend.”[63] Eliza referred to him as “my faithful ’tho humble friend Billy—who has evinced his attachment through every change of my destiny.”[64] Soon before her death in 1831, Eliza entrusted Costin with taking her most treasured Mount Vernon relic—John Trumbull’s portrait of George Washington—to her brother Wash at Arlington House, and she expected that Costin would “consult with” Wash about where best to hang it.[65] She stored her will with him and, upon her death, left him “some bequest for his grateful conduct.”[66] It was perhaps at the same time that she gave him at least one of her porcelain figures.

When William Costin died in 1842, aged sixty-two, testimonials of respect poured in. The Bank of Washington’s board of directors “unanimously passed a resolution expressive of their respect for his memory” and gave his family fifty dollars. His obituary in Washington’s Daily National Intelligencer praised his character and “excellent qualities,” and seventy carriages of white residents followed by a procession of free Black men on horseback (joined by Francis Scott Key) attended his funeral.[67] John Quincy Adams (1767–1848) invoked Costin’s sterling reputation as a free Black man to argue against restricting suffrage to white voters; after all, Costin was “as much respected as any man in the District.”[68] It did not appear that any of the respect for Costin was tied to his ancestry; if anybody in his lifetime knew of it, either they did not record the fact, or the evidence has not survived.

At Costin’s death, he left a substantial estate to his surviving children. Likely in recognition of the importance of property ownership for free Blacks, he stipulated in his will that no one could “sell, mortgage, or convey away in any way whatever” the land and houses he was conveying, as it was his “wish and desire that [the properties] shall descend from heir to heir forever.” His primary residence on A Street and its contents went to his daughters, with his eldest surviving daughter in charge. Someone scrawled a rough inventory of his household goods on a scrap of paper, now hard to decipher from fading, fold lines, and idiosyncratic spelling. But the very first item on the list is “5 mintle ornamen[ts].”[69] It seems quite likely that these were five of the twelve original porcelain figures, and like Eliza Custis and George Washington before him, Costin had displayed them on the mantelpiece. Certainly at least one of these ornaments was part of the original set, because the provenance for the figure of Le Peinture known today traces back to Costin’s daughter, Harriet Parke Costin.

Tracing La Peinture to the Present Day

William Costin’s daughter, Harriet Parke Costin, was born a free person of color in 1819.[70] According to one account, Harriet inherited several Washington relics after her father’s death in 1842, including a Windsor chair that was “in the library at Mt. Vernon” (fig. 17) along with a vase and the biscuit porcelain figure that was “one of a set which stood on a mirror on the dining table.”[71] She married Richard Phisk (or Fisk[e]) (1823–1863) several years later, and they lived in one of her father’s homes that she inherited along with her sisters. Eleven years on she appears in the record as a widow living in the same place.[72]

In need of an income, Harriet got a job in 1867 in the House of Representatives offering “services in the ladies’ retiring room,” where she worked through 1874.[73] A short account of her life by the former Union spy Elizabeth Van Lew (1818–1900) notes that Harriet had gotten the job with the help of Congressmen Rufus Paine Spalding and Thaddeus Stevens. That she knew such powerful figures may well be due to her father’s extensive connections. Whether it was through her father, these congressmen, or by other means, she apparently met Edwin Barber Morgan (1806–1881), who served in Congress from 1853 to 1859. At some point before Harriet’s death in 1881, she sold Morgan the porcelain figure, the Windsor chair, and a vase with Washington provenance.[74]

Edward Barber Morgan was elected to the United States Congress in 1853 as an anti-slavery Republican from Aurora, New York (fig. 18). Morgan had begun his career as a merchant working for his father, shipping grain and wool, and boat building before moving to larger enterprises. He helped found Wells, Fargo, and Company, the express service that provided shipping and fast post from the East Coast to California. He served on the boards of several banks and manufacturing companies, and he was a major, early shareholder in the New York Times.

During his time in Congress, Morgan focused his attentions on the cause of anti-slavery. He was among the first congressmen to help Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner when Congressman Preston Brooks attacked him on the floor of the United States Senate in retaliation for an anti-slavery speech. Given the proximity of the Costin houses to the United States Capitol and Harriet Costin’s later role in the ladies’ retiring room, the two likely met during Morgan’s time as a member of the House of Representatives.[75]

Congressman Morgan likely displayed the porcelain figure, Windsor chair, and vase in his house in Aurora, New York. Morgan’s daughter, Louise M. Zabriskie, in whose line the piece descended, carefully recorded the provenance as recounted by her father. She wrote that Harriet Fiske was the “daughter of body servants of General and Mrs. Washington.” Philadelphia “Delphy” Judge served as a spinner on the Mansion House Farm at Mount Vernon, and she was the sister of Ona Judge Staines, who served as Martha Washington’s chambermaid. Zabriskie also recorded that William Costin owned numerous Washington relics and that La Peinture had been “one of a set which stood on a mirror on the dining table,” a fact that would not have been well known in the middle of the nineteenth century. Because the porcelain figure was French, it had acquired the legend that it had been “presented to Mrs. Washington by General Lafayette,” a common description given to many French goods in the Washington household by later generations.[76] The Morgan/Zabriskie family continued to prominently display their Washington relics throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Conclusion

The rediscovery of La Peinture has allowed for the reappraisal of the surtout purchased by George Washington through his agent Gouverneur Morris. Although scholars have long known of the service’s existence and the famous correspondence surrounding the purchase, the emergence of the single figure and additional documentary research have uncovered the story the two men intended to tell through the objects themselves. The surtout embodied the two men’s vision of an agrarian nation looking back to Roman models as the basis of their new government. Beyond offering insights into the ceramics themselves and their use by the first president, the full provenance of Le Peinture provides an important piece in puzzling together the story of William Costin and his relationship with the Custises. The transfer of a valuable Washington object to Costin strengthens the case that Costin was, in fact, related to the Custis family. One porcelain figure, over two hundred years old and less than a foot tall, illuminates expansive stories about a lost artwork, a presidency, and a little-known but important Black member of the Custis family.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors wish to thank Amy Hudson Henderson, Amanda Isaac, Jessie MacLeod, Mike Montgomery, Iris de Rhode, Susan P. Schoelwer, Mary V. Thompson, John Whitehead, and Stephen L. Zabriskie.

The stewards and valets changed with time. Samuel Fraunces, Patrick Kennedy, and John Hyde served as hired stewards. Christopher Sheels and Austin Steward served as enslaved valets, while William Osborne and Jacob Baur served as hired valets. The history of this plateau is discussed in Susan Detweiler, George Washington’s Chinaware (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1982), pp. 107–118. For more on the symbolic meaning of the classical figures, see Amy Hudson Henderson, “French & Fashionable: The Search for George and Martha Washington’s Presidential Furniture,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2009), pp. 79–155. The most authoritative work on French biscuit porcelain is Régine de Plinval de Guillebon, Les biscuits de porcelaine de Paris XVIIe–XIXe siècle (Dijon: Éditions Faton, 2012). George Washington identifies the “twelve single images” as the “Arts and Sciences” and the “large group” as “Apollo instructing the Shepherds” in George Washington to Clement Biddle, January 29, 1798, Papers of George Washington Digital Edition, Retirement Series, 2008, Rotunda, University of Virginia Press, https://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/GEWN.html (cited hereafter as PGW/DE). The description of the placement of the figures on the table is taken from Gouverneur Morris to George Washington, January 24, 1790, PGW/DE. Morris wrote, “I expect that this Letter will accompany three cases containing a Surtout of seven Plateaus and the ornaments in Biscuit; also three large glass covers for the three Groups which may serve both for ornaments to the Chimney Piece of a drawing Room (in which Case the Glasses will preserve them from the Dust and Flies) or for the Surtout. The Cases must be knocked to Pieces very carefully after taking off the Top first and then the sides and Ends. The Manufacturers promised me that instructions for unpacking should accompany the Cases. Enclosed is his Note of the Contents of the several Cases. There are in all three Groups two Vases and twelve figures. The Vases may be used as they are or when occasion serves, the Tops may be laid aside and the Vases filled with natural flowers. When the whole Surtout is to be used for large Companies the large Group will be in the middle the two smaller ones at the two Ends—the Vases in the Spaces between the three and the figures distributed along the Edges or rather than along the Sides. I shall send you the Amount by another opportunity and the other Articles I shall procure in England. P.S. I have directed the Charges of Transportation to be paid by Messrs Wm Constable and for to whom you will be so kind as to replace the Amount. To clean the Biscuit warm water is to be used and for any things in the Corners a Brush such as is used for painting in Water Colours.

The figure survives in the ceramics collection of George Washington’s Mount Vernon (W-2133), Mount Vernon, Virginia. The piece is marked with an incised “A2.”

Louise Morgan Zabriskie, undated manuscript, private collection.

Louise Morgan Zabriskie, undated manuscript, private collection.

Tobias Lear to Clement Biddle, June 8, 1789, as quoted in Detweiler, George Washington’s Chinaware, p. 211.

George Washington to Gouverneur Morris, October 13, 1789, PGW/DE Presidential Series.

Barbara G. Carson, Ambitious Appetites: Dining, Behavior, and Patterns of Consumption in Federal Washington (Washington, D.C.: American Institute of Architects Press, 1990).

Amy Hudson Henderson, “Furnishing the Republican Court: Building and Decorating Philadelphia Homes, 1790–1800” (Ph.D. diss., University of Delaware, 2008), pp. 161–216. After the American Revolution, George Washington asked the marquis de Lafayette to serve as his proxy shopper when he requested a list of plated wares for the tea and dining tables. He explained to Lafayette his reasons for asking his help, saying he “might not be able to explain so well to them [French merchants], as to you, my wants, who know our customs, taste & manner of living in America.” Washington also believed that he could rely upon Lafayette’s judgment “to prevent impositions upon me, both in price & workmanship, than on those of a stranger.” George Washington to Marquis de Lafayette, October 30, 1783, PGW/DE Presidential Series. Prior to the American Revolution, George Washington relied upon the London agents through whom he sold his tobacco to serve as proxy shoppers for him. He often complained that the agents sent older and less fashionable goods to him, because he had few other options.

Gouverneur Morris, A Diary of the French Revolution, edited by Beatrix Cary Davenport, 2 vols. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1939), 1: 263.

Ibid., 1: 24–25.

After the outbreak of the French Revolution, the firm became known as Dihl et Guérhard. Régine de Plinval de Guillebon, La manufacture de porcelaine de Guérhard et Dihl dite du duc d’Angoulême, French Porcelain Society Monograph 4 (London: French Porcelain Society, 1988), pp. 1–22. The authors are grateful to John Whitehead for alerting them to this source.

Morris decided to buy the service for George Washington at Angoulême on January 15. He finalized the order in visits to the warerooms on January 18, 20, and 21. Morris, A Diary, 1: 366–371.

Gouverneur Morris to George Washington, January 24, 1790, The Papers of George Washington, Presidential Series, vol. 5 (January–June 1790), edited by Dorothy Twohig et al. (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1996), p. 57. (Hereafter cited as PGW/PS.)

Gouverneur Morris to George Washington, January 24, 1790, PGW/PS, p. 48.

Caroline Winterer, The Culture of Classicism: Ancient Greece and Rome in American Intellectual Life, 1780–1910 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press), pp. 10–44.

George Washington to Gouverneur Morris, April 15, 1790, PGW/PS, p. 334. Several other fashionable Americans acquired a plateau and biscuit porcelain figures from France, including Edward Lloyd IV and his wife, Elizabeth, who purchased a plateau in 1792. A number of these figures and the plateau survive at Wye House. Alexandra Alevizatos Kirtley, “Survival of the Fittest: The Lloyd Family’s Furniture Legacy,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2002), p. 24. Thomas Handasyd Perkins of Boston likely purchased a set during his time in France in 1795, and two of the Sèvres figural groups survive at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Donna Corbin, “Trifles from a Boston Collection,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2005), pp. 213–216. Thomas Jefferson acquired biscuit porcelain figures for himself and Abigail Adams in 1784 and 1785. For more on this purchase, see Susan Stein, The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1993), p. 237.

Theophilus Bradbury to Harriet Bradbury, December 26, 1795 (photocopy), Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association, Mount Vernon, Virginia (cited hereafter as MVLA).

George and Martha Washington’s Apollon instruisant les bergers does not survive. Régine de Plinval de Guillebon has identified examples from the Angoulême manufactory in the collection of H.M. King Charles III (inv. 33943) and in the Museo Arqueógico Nacional in Madrid. The pieces survive on two different bases. The Royal Collection example features a classical pedestal with the title in raised lettering, while the Madrid base is a continuation of the sculptural composition. George Washington’s figures likely did not have bases.

Detweiler, George Washington’s Chinaware, p. 112.

Ibid., pp. 214–219.

Thomas Jefferson to Abigail Adams, September 25, 1785, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson Digital Edition, 2008–2023, Rotunda, University of Virginia Press, https://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/TSJN.html.

Thomas Bulfinch, Bulfinch’s Mythology, edited by Richard P. Martin (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, Inc., 1991), pp. 20–21.

George Washington to the Marquis de Lafayette, June 18, 1788, PGW/DE Confederation Series.

George Washington to François Jean de Beauvoir, marquis de Chastellux, April 25 and May 1, 1788, PGW/DE.

Bulfinch, Bullfinch's Mythology, pp. 56–57.

John Adams to Abigail Adams, May 12, 1780, The Adams Papers Digital Edition, 2008– 2023, Rotunda, University of Virginia Press, https://rotunda.upress.virginia.edu/founders/ ADMS.html.

Ibid.

Both of these delicate elements have been lost, but the current owner recalls seeing them in the mid-twentieth century.

Plinval de Guillebon, Les biscuits de porcelaine, pp. 56–58.

Samuel L. Mitchill to Catharine Mitchill, February 2, 1804, Samuel Latham Mitchill Papers, William Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Plinval de Guillebon, La manufacture de porcelaine, pp. 1–22.

Ibid.

George Washington to Clement Biddle, August 14, 1797, PGW/DE Retirement Series.

George Washington to Clement Biddle, August 23, 1797, ibid.

George Washington to Clement Biddle, January 29, 1798, ibid.

George Washington, General Ledger C, 1790-1799, p. 19, Morristown National Historical Park, Morristown, New Jersey. George Washington paid Clement Biddle on April 10, 1798, for packing the figures, and they arrived at Mount Vernon sometime around May 1798.

The “Images” in the New Room were valued at $100. The “2 Sets Platteaux,” valued at $100, appear in the “Lumber Rooms,” storage spaces in the garret. “Inventory of the Contents of Mount Vernon made after the death of General Washington,” 1799–1800, MVLA.

The mirrored plateau descended through Elizabeth Parke Custis Law to her granddaughter Eleanor Agnes Rogers Goldsborough (1822–1906), who donated several segments of the plateau to Mount Vernon in 1895.

On Eliza’s childhood, see Cassandra A. Good, First Family: George Washington’s Heirs and the Making of America (New York: Harper Collins, 2023), chap. 1 and 2.

On Eliza and Thomas’s relationship, see Good, First Family, chap. 2; Rosemarie Zagarri, “The Empire Comes Home: Thomas Law’s Mixed-Race Family in the Early American Republic,” in India in the American Imaginary, 1780s to 1880s, edited by Anupama Arora and Rajender Kaur (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), pp. 75–108.

Samuel L. Mitchill to Catharine Mitchill, February 2, 1804, Samuel Latham Mitchill Papers, William Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan; On the Laws’ houses, see Allen C. Clark, Greenleaf and Law in the Federal City (Washington, D.C.: W.F. Roberts, 1901), pp. 250-253; C. M. Harris, ed., The Papersof WilliamThornton, vol. 1, 1781–1802 (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1995), pp. 579, 586–88.

On Eliza and her siblings’ purchase and use of objects from Mount Vernon, see Cassandra Good, “Washington Family Fortune: Lineage and Capital in Nineteenth-Century America,” Early American Studies 18, no. 1 (Winter 2020): 90–133.

There has been considerable confusion about the identity of Costin’s mother, who previous scholars believed to be the child of Martha Washington’s father and a woman with Native American background. For a full discussion of the evidence, see Cassandra Good, “Ancestry of William Costin,” George Washington Digital Encyclopedia, MVLA, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/ancestry-of-william-costin/.

Moses B. Goodwin, Special Report of the Commissioners of Education on the Condition and Improvement of Public Schools in the District of Columbia: Submitted to the Senate June, 1868, and to the House, with Additions, June 13, 1820 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1871), pp. 203–204; Elizabeth Louisa Van Lew, Album, 1845–1897, Virginia Museum of History and Culture, Richmond, Virginia; Costin Family Tree shared by Marcia Carter in 1981, curatorial files, MVLA.

The complete names are spelled out in the manumissions and William Costin’s will: Louisa Parke, Ann Parke, Charlotte Parke, Frances “Fanny” Parke, Harriet Parke, William Custis Parke, and George Calvert Parke. See Helen Hoban Rogers, Freedom & Slavery Documents in the District of Columbia, 3 vols. (Baltimore, Md.: Gateway Press, 2007), 1: 52, and Will of William Costin, Washington, D.C., U.S., District and Probate Courts, 1737–1952, Wills, Boxes 0014 Quinlin, Tasker C.–0018 Degges, John, 1837–1847, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/9083/. On the Parke name, see “Virginia Gleanings in England,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 20, no. 4 (1912): 372; Kathryn Gehred, “The Dunbar Lawsuit: How a Decades-Long Scandalous Court Case Threatened George Washington’s Estate,” February 26, 2018, Washington Papers, Miller Center, University of Virginia, https://millercenter.org/president/washington/washington-papers/dunbar-lawsuit; Joseph McMillan, “Changes of Arms in Colonial North America: The Strange Case of Custis,” Coat of Arms, 3rd ser., 11, no. 230 (2015): 130–33.

Thomas Law to Negro William, 27 July 1802; and, Thomas Law to Nancy Holmes, 28 July 1802, District of Columbia Land Records, Book H8, p. 413, District of Columbia Courthouse; see Rogers, Freedom & Slavery, 1: 20.

While there is no record of her dowry, given that these names do not appear on the list of people she inherited from Mount Vernon in 1802, this is the most likely way she acquired them (see “List of the different Drafts of Negroes, [1802],” Peter Family Papers, MVLA).

Letitia Woods Brown, Free Negroes in the District of Columbia, 1790-1846 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972), pp. 9–12.

Letitia Woods Brown, Free Negroes in the District of Columbia, 1790-1846 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972), pp. 9–12.

Ibid., pp. 139–40; Constance McLaughlin Green, Secret City: A History of Race Relations in the Nation’s Capital (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2015), pp. 19, 25, 32.

Green, Secret City, pp. 20, 40-41.

Costin obituary, Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C.), June 1, 1842.

Brown, Free Negroes, pp. 129–32; Green, Secret City, p. 27.

The lot was a slice of the land where the present-day Library of Congress Jefferson Building stands, across from what was then called “Capitol Square,” where the still in-progress U.S. Capitol building stood and not far from where Thomas and Eliza had lived during their marriage.

Henry S. Robinson, “Some Aspects of the Free Negro Population of Washington, D.C., 1800–1862,” Maryland Historical Magazine 64, no. 1 (Spring 1969): 50–52. For Costin’s will, see Washington, D.C., U.S., District and Probate Courts, 1737–1952, Wills, Boxes 0014 Quinlin, Tasker C 0018 Degges, John, 1837-1847, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/9083/.

1820 Federal Census; Judah Delano, The Washington Directory (Washington, D.C.: William Duncan, 1822).

Brown, Free Negroes, pp. 152, 165.

Robinson, “Some Aspects of the Free Negro Population,” p. 63.

For the case (and the quote) see Costin v. Washington, 2 Cranch, C.C. 254.

Constance McLaughlin Green, Washington, vol. 1, Village and Capital, 1800–1878 (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1962), pp. 25–26; Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove, Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), p. 63. .

Robinson, “Some Aspects of the Free Negro Population,” p. 51; Rogers, Freedom & Slavery, 1: 52.

Charles Fenderich, after S. M. Charles, William Costin. ‘A tribute to worth by his friends,’ lithograph, ca. 1841, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

Eliza Custis Law to John Law, October 12, 1808; Lawrence Lewis to William Costin, October 6, 1813; Eleanor Custis Lewis to William Costin, June 12, 1816, Peter Family Papers, MVLA.

Eleanor Custis Lewis to William Costin, June 12, 1816, ibid.

Eliza Custis Law to John Law, August 8, 1809, ibid.

Eliza Custis Law to George Washington Parke Custis, July 15, 1830, Mary Custis Lee Papers, Virginia Museum of History and Culture.

Thomas Law to Lloyd Rogers, undated (likely early 1832), Peter Family Papers, MVLA.

Daily National Intelligencer, June 1, 1842; Emancipator and Free American (Boston, Mass.), June 9, 1842 (quoting from Daily National Intelligencer).

Daily Globe (Washington, D.C.), June 2, 1842.

Will of William Costin, Washington, D.C., U.S., District and Probate Courts. Wills, Boxes 0014 Quinlin, Tasker C –0018 Degges, John, 1837–1847, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/9083/. No values are listed on the probate inventory.

Obituary, Daily Critic (Washington), October 28, 1881.

Louise Morgan Zabriskie, undated manuscript, private collection. Zabriskie also noted the important detail: “This one La Peinture has the Royal factory mark ‘Le deas d’Angoulême a Paris [sic].’”

It appears that Harriet married in both D.C. and Maryland, and in each record her husband’s name is spelled differently; see Washington, D.C., U.S., Compiled Marriages, 1826–1850, November 19, 1849, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/ 5277/; Maryland, U.S., Compiled Marriages, 1655-1850, November 22, 1849, Ancestry.com, https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/7846/. Their addresses and her widowed status appear in the 1853 and 1864 city directories; see Alfred Hunter, The Washington and Georgetown Directory (Washington, D.C.: Printed by Kirkwood and McGill, 1853); Andrew Boyd, Boyd’s Washington and Georgetown Directory (Washington, D.C.: A. Boyd, 1864). It is unclear what happened to Richard Phisk, but a Rich[ar]d Fisk of Virginia, born 1823, died in California in 1863; see N. Gray and Co., Register, book p. 1-300, San Francisco History and Archive Center, San Francisco Public Library (digitized in: California, San Francisco Area Funeral Home Records, 1835-1979, database with images, FamilySearch, https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/1385518 [the transcription mistakenly identifies his birthplace as Vermont]); “Memorials: Richard Fisk,” Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/186924517/richard-fisk.

House of Representatives, 40th Congress, 3d Session, Mis. Doc. No. 25, p. 13; U.S. Statutes at Large, vol. 18, part 3, p. 208. These publications show the first and last times she was paid for this position, in 1867 and 1874 respectively; she also appears in congressional records in the intervening years in the same role.

Louise Morgan Zabriskie, undated manuscript, private collection.

For more information on Edward Barber Morgan, see General Catalogue of the Officers and Students with Historical Sketches of the Founder, Henry Wells, and the Hon. Edwin Barber Morgan, Its Principal Benefactor, of Wells College (Aurora, N.Y., 1894), pp. 29–35; and The National Cyclopedia of American Biography, vol. 103 (New York: James T. White and Company, 1906), p. 218.

Louise Morgan Zabriskie, undated manuscript, private collection.