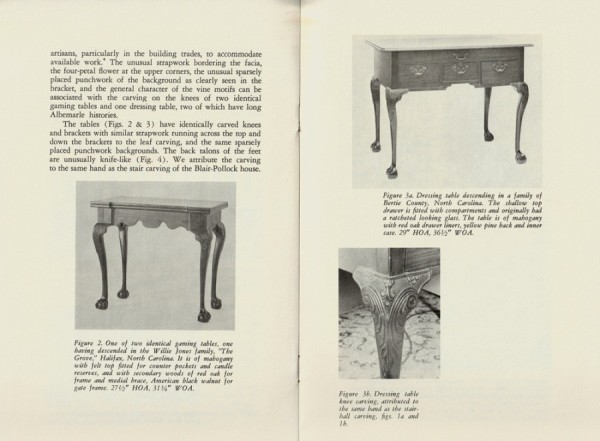

Pages from Frank L. Horton, “Carved Furniture of the Albemarle: A Tie with Architecture,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 1, no. 1 (May 1975): 14–20. (Photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The two tables are illustrated below in figs. 39 and 41.

Illustration from John Bivins Jr., The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, 1700–1820 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1988), p. 157. (Photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) This armchair is illustrated below in fig. 11.

Cupola House, 408 South Broad Street, Edenton, North Carolina, ca. 1758. (Courtesy, Historic American Buildings Survey; photo, Thomas T. Waterman, 1939).

Hall, the Cupola House, 1757–1759, 19 1/2 x 15 1/2 ft. (Courtesy, Cupola House Association, Inc.; photo, Brooklyn Museum.) This photo shows the installation of the woodwork at the Brooklyn Museum. The woodwork has recently been given by the Brooklyn Museum to the Cupola House Association, Inc. for reinstallation in 2025.

Chimneypiece on the second floor of the Cupola House. (Photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the carved truss on the right of the chimneypiece illustrated in fig. 5. (Photo, the author.)

Detail of a stair bracket in the Cupola House. (Photo, the author.)

Detail of the carved leafage on the stair bracket illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, the author.)

Armchair, vicinity of Edenton, North Carolina, 1745–1765. Mahogany and cherry with yellow pine. H. 39 1/2". (Courtesy, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Museum Purchase.) This rear seat rail is branded “JOHN COX / EDENTON NC” (see fig. 13). All of the chairs in this group are dimensionally the same.

Armchair, vicinity of Edenton, North Carolina, 1745–1765. Mahogany and cherry with yellow pine. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, vicinity of Edenton, North Carolina, 1745–1765. Mahogany and cherry with cypress and beech. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This armchair is illustrated in the publication cited in fig. 2.

Armchair, vicinity of Edenton, North Carolina, 1745–1765. Mahogany and cherry with yellow pine. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the brand on the armchair illustrated in fig. 9.

Detail of a fragment of wool worsted trapped under a wrought nail on the beech slip seat of the armchair illustrated in fig. 11 (left) and two threads trapped under a wrought nail on the yellow pine slip seat of the armchair shown in fig. 10 (right). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.) These are the only slip seats retaining evidence of original show cloth. The chair thought to have been covered in leather (fig. 9) only has evidence of its linen foundation upholstery.

Detail showing the numbering on the rear seat rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

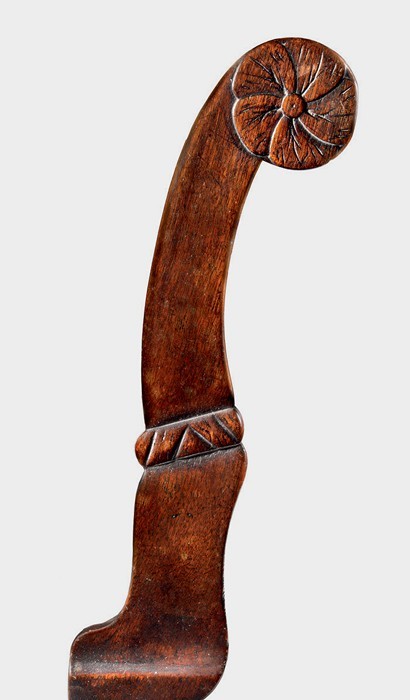

Detail of an arm on the armchair illustrated in fig. 11. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Rear view of the armchair illustrated in fig. 11. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

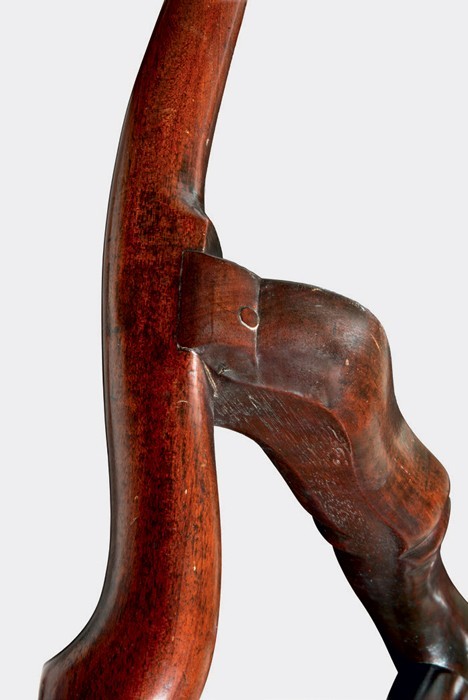

Details showing an arm support and side rail of the armchairs illustrated in figs. 11 (left) and 12 (right). On all of the armchairs in this group, the maker inserted thin strips of wood to fill in the gaps between the flat undersides of the arm supports where they meet the molded seat rails, as seen on the right. The chair on the left is missing the original filler strip. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

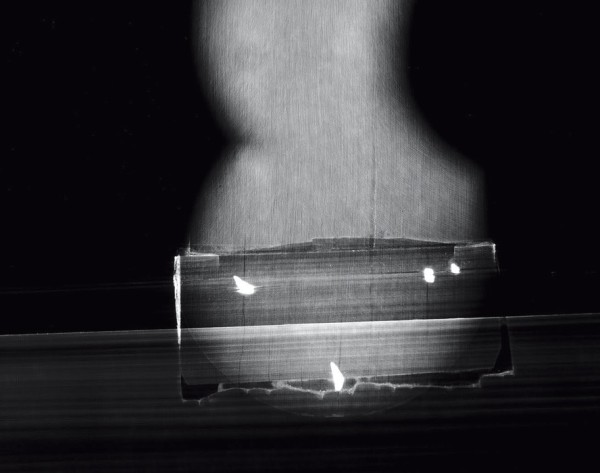

X-radiography showing the tenoned and nailed joint of an arm support and seat rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 9. (Photo, Chris Swann.)

Detail showing how the arms of the chair illustrated in fig. 12 are attached to the rear stiles. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the overlapping glue blocks reinforcing a seat rail/leg joint of the armchair illustrated in fig. 9.

Detail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 12, showing how the knee blocks are attached to the legs and rails and how the blocks and rails were undercut. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

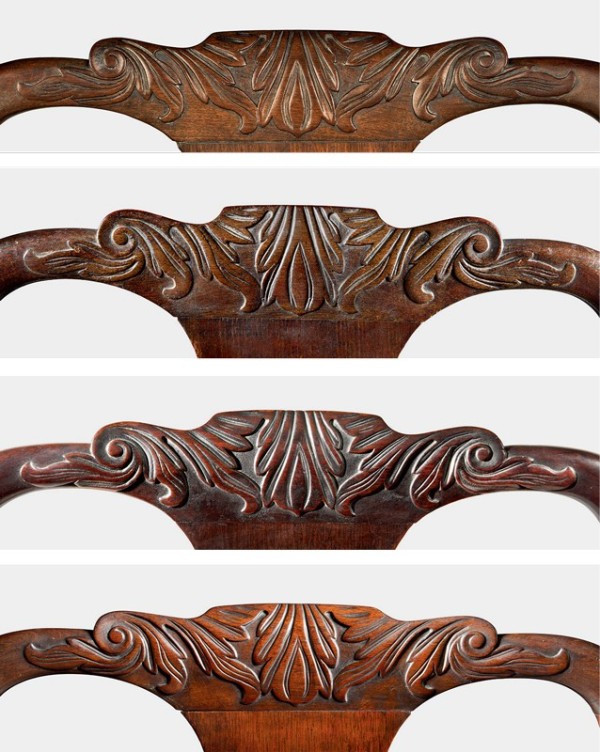

Details showing the crest rail carving of the armchairs illustrated (from top to bottom) in figs. 9–12. (Photos [lower three], Gavin Ashworth.)

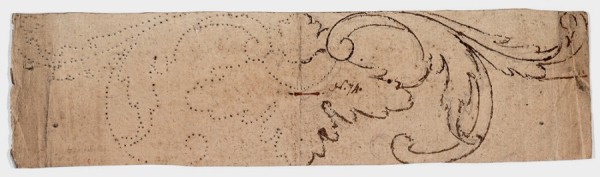

Carving pattern from the shop of Gideon Saint (1729–1799), London, ca. 1760. (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo, Art Resource NY.)

Details showing the splat rosettes of the armchairs illustrated in figs. 11 (left) and 12 (right). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

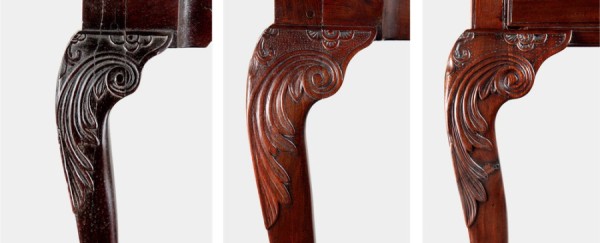

Details showing the knee carving of the armchairs illustrated (from left to right) in figs. 9–12. (Photos [right three], Gavin Ashworth.)

Details showing the knee carving of the armchairs illustrated (from left to right) in figs. 9–12. (Photos [right three], Gavin Ashworth.)

Details showing the knee carving of the armchairs illustrated (from left to right) in figs. 9–12. (Photos [right three], Gavin Ashworth.)

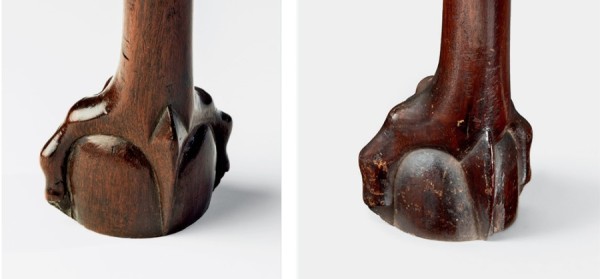

Details showing the claw-and-ball feet of the armchairs illustrated (from left to right) in figs. 9–12. (Photos [right three], Gavin Ashworth.)

Details showing the claw-and-ball feet of the armchairs illustrated (from left to right) in figs. 9–12. (Photos [right three], Gavin Ashworth.)

Close view of the carving on the crest rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This armchair and the example illustrated in fig. 9 have evidence of stippling around the central leaf element of their crests.

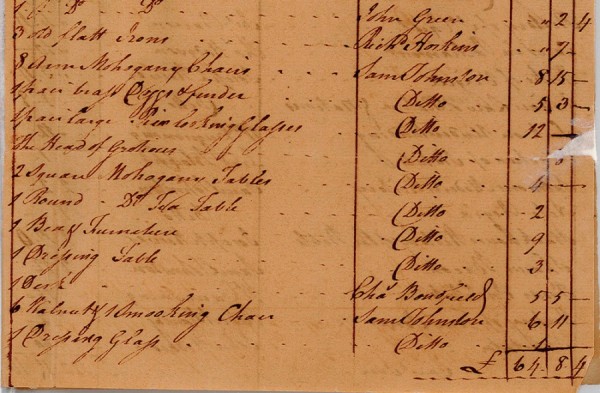

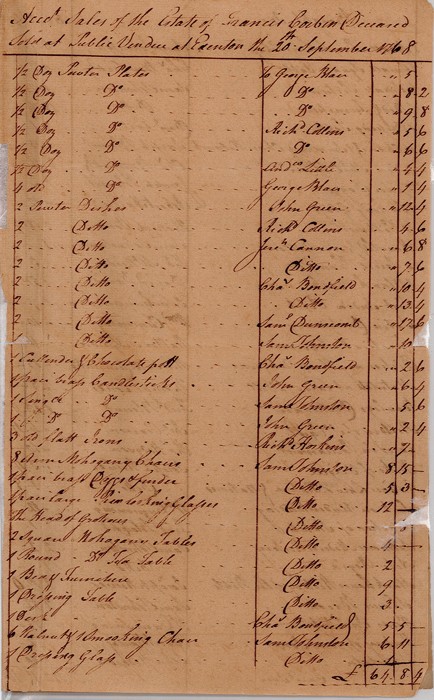

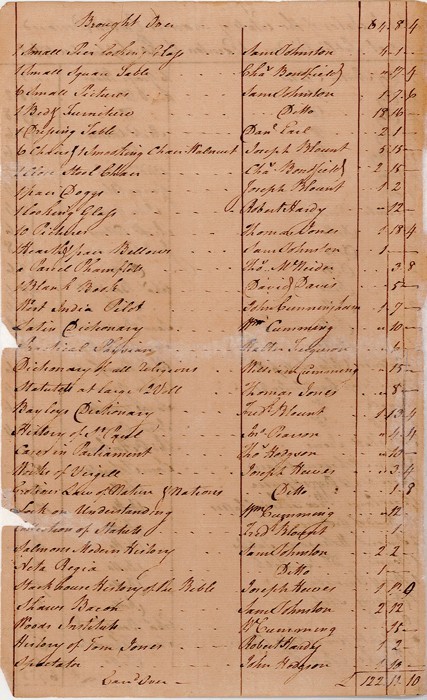

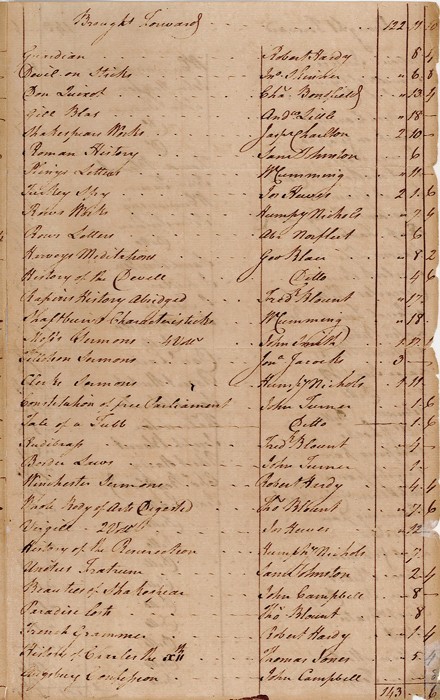

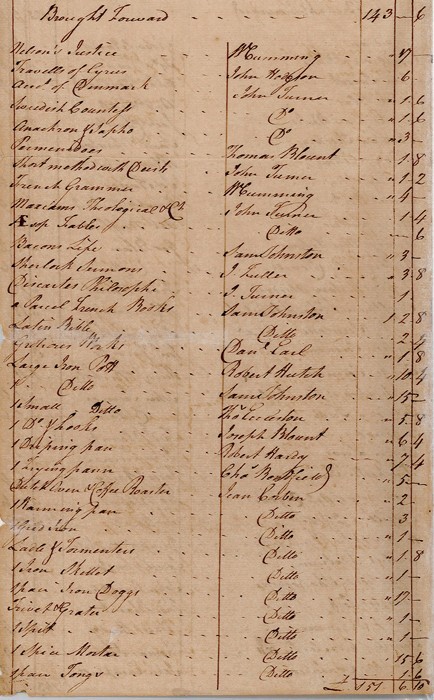

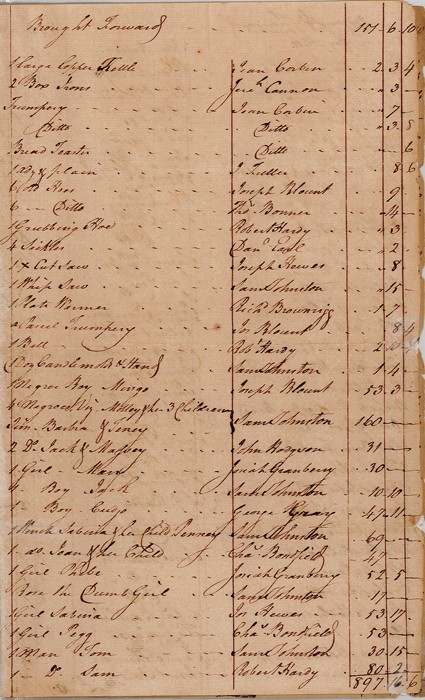

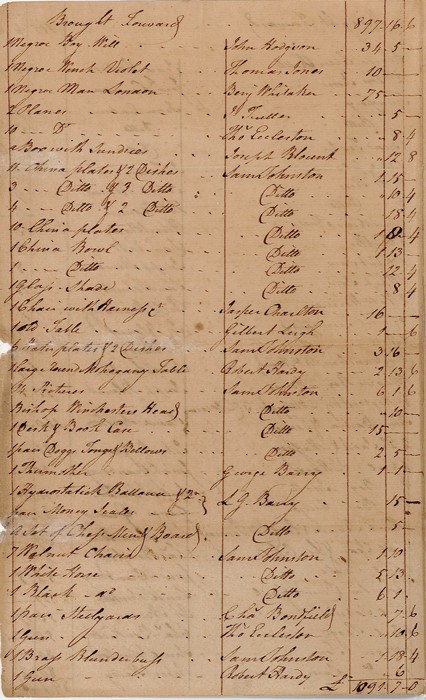

Detail of the “Acct. Sales of the Estate of Francis Corbin Deceased,” September 20, 1768. (Courtesy, State Archives of North Carolina, Raleigh.) For the full account, see Appendix.

Side chair attributed to Thomas White, Perquimans County, North Carolina, ca. 1768. Walnut with yellow pine. H. 36 1/8". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Table (fragmentary), vicinity of Edenton, North Carolina, 1745–1765. Mahogany. (Courtesy, Sotheby’s American Heritage Society Auction of Americana [New York: Sotheby’s, November 27–30 and December 1, 1979], lot 1725; photo, MESDA Object Database Files NN-224.) The legs are all that survive from the original table.

Card table, vicinity of Edenton, North Carolina, 1745–1765. Mahogany and cherry with yellow pine and cherry. H. 27 3/8", W. 29 1/2" (top), D. 14 3/8" (top) (closed). (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The knee blocks are replaced.

Detail showing the knee carving on the card table illustrated in fig. 35 (left) and the armchair illustrated in fig. 12 (right). (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Underside of the card table illustrated in fig. 35. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Card table, vicinity of Edenton, North Carolina, 1760–1775. Mahogany with red oak and walnut. H. 27 3/8", W. 31 3/4" (top), D. 15 3/4" (closed). (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This table and the example shown in fig. 39 are an original pair.

Card table, vicinity of Edenton, North Carolina, 1760–1775. Mahogany with red oak and walnut. H. 27 3/8", W. 31 3/4" (top), D. 15 3/4" (closed). (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This table and the example shown in fig. 38 are an original pair. This table is illustrated in the article cited in fig. 1.

Card table, vicinity of Edenton, North Carolina, 1760–1775. Mahogany with oak, birch, and tulip poplar. H. 27 7/8", W. 31" (knees), D. 16" (knees). (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The top and knee blocks are replaced.

Writing table, vicinity of Edenton, North Carolina, 1760–1775. Mahogany with oak and yellow pine. H. 29", W. 36 1/2", D. 21 3/4". (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This table is illustrated in the article cited in fig. 1.

Details showing the knee carving (from left to right) on the card tables illustrated in figs. 38 and 40 and on the writing table illustrated in fig. 41. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Details showing the knee carving (from left to right) on the card tables illustrated in figs. 35 and 38. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.) The knee designs feature linear leafage, but the outlining, modeling, and shading are very different.

Details showing a foot of the armchair illustrated in fig. 9 (left) and of the writing table illustrated in fig. 41 (right). (Photo [on right], Gavin Ashworth.) These feet differ in almost every respect. The foot of the armchair has a taller ball and no webbing, whereas that of the writing table has a more flattened ball and webbing. These feet also differ in the modeling of the front and side toes.

Details showing a foot of the armchair illustrated in fig. 9 (left) and of the writing table illustrated in fig. 41 (right). (Photo [on right], Gavin Ashworth.) Although both feet have blade shaped rear toes, the toes on the armchair originate higher on the ankle and are broader, with facets at the top. These differences can be seen on all of the furniture in the early and later groups.

Underside of the card table illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the fly rail joint and an overlapping knee block on the card table illustrated in fig. 38. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the carved frieze of the staircase from the Blair House, Edenton, North Carolina, ca. 1765. (Courtesy, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) The hallway and one room from the Blair House are installed in the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.

Details of the knee carving on the writing table illustrated in fig. 41. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail approximating figure 52 in Don Jordan, Tom Newbern, and Jim Melchor, The Cupola House Carver (Edenton, N.C.: Elizabeth Van Moore Foundation, 2021). (Photo, Rob Hunter.) The authors denied permission to reproduce illustrations from their book.

Close-up of the leaf carving on the bracket illustrated in fig. 7. (Photo, Rob Hunter.) As this detail reveals, the carver responsible for the work in the Cupola House had far more ambition than skill. The leaves are not modeled, their lobes are articulated with erratic “shading” cuts, and the ground is rough and uneven. Although not rising to the level of workmanship expected from someone trained as a carver, the leaf carving on the two groups of furniture illustrated and discussed here is far superior to the Cupola House work. The ground around the furniture carving is reasonably well controlled, and the leaves are modeled and shaded.

Artist’s rendering of the tea table discussed in “Cupola House Tea Table” and illustrated in figure 23 of Jordan, Newbern, and Melchor, The Cupola House Carver. (Artwork, Wynne Patterson). The authors denied permission to reproduce illustrations from their book.

Tea table, vicinity of Edenton, North Carolina, or English, 1750–1770. Mahogany. H. 27 3/8", Diam. 30 1/4". (Private collection; MESDA Object Database Files S-12173.)

“Acct. Sales of the Estate of Francis Corbin Deceased”

“Acct. Sales of the Estate of Francis Corbin Deceased”

“Acct. Sales of the Estate of Francis Corbin Deceased”

“Acct. Sales of the Estate of Francis Corbin Deceased”

“Acct. Sales of the Estate of Francis Corbin Deceased”

“Acct. Sales of the Estate of Francis Corbin Deceased”

“Acct. Sales of the Estate of Francis Corbin Deceased”

IN 1972, THE MUSEUM OF Early Southern Decorative Arts launched an ambitious documentary and field research program envisioned by Frank L. Horton and funded initially by the National Endowment for the Arts. One of the earlier discoveries was the probable production of carved Georgian furniture in the vicinity of Edenton, North Carolina. The first pieces identified were a pair of card tables and a writing table, all of which were published by Horton in 1975 in the inaugural volume of the Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, where the furniture was attributed to the carver of the frieze and brackets from the Blair House in Edenton (fig. 1).[1] The museum’s research and acquisition efforts also led to the identification of a group of armchairs that appears to predate the tables published by Horton, a fragmentary card table from the same shop, and three related but later dining tables. In his 1988 monograph The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, 1700–1820, furniture scholar John Bivins Jr. described all of this furniture as being from the “Edenton School” and proposed that two different hands were responsible for the carving (fig. 2).[2] Most recently, Don Jordan, Tom Newbern, and Jim Melchor have asserted that all of this carving is by the craftsman responsible for the architectural ornament in the Cupola House (fig. 3) and that Samuel Black is “the only logical candidate to have made these chairs and other members of the carved Edenton group.” In a subsequent essay, titled “The Cupola House Tea Table,” the authors refer to the subject object, and by extension to all of the carved furniture in the Edenton school, as “proven to be by Samuel Black.” Jordan, Newbern, and Melchor’s thorough biography of Black and other furniture makers associated with him makes these craftsmen likely candidates for some of this work, but the authors provide no evidence that rises to the level of proof.[3] This article, which includes related objects not previously published, will assess the conclusions reached by all of the aforementioned authors and provide compelling evidence both that the carving is by at least three different hands and that the furniture is likely from two different shops.

The Cupola House

Herman J. Heikkenen’s dendrochronology study of the yellow pine structural members of the Cupola House demonstrated that the trees were felled after the growing season of 1757 and immediately processed into timber. His findings refuted much previous scholarship, which asserted that the Cupola House was built significantly earlier—possibly by James Sanderson—and subsequently acquired and renovated by Francis Corbin (d. 1767). The dendrochronology date indicates that Corbin was the original owner, and the house was completed about 1759.[4] Corbin’s residency was relatively short. He died in 1767, leaving his estate to his wife, Jean (possibly born Junds, widow of James Innes) (d. 1775). During the settlement of Corbin’s estate, Chowan County carpenter Robert Kirshaw (d. 1772) sued “Jean Corbin, administratrix of all & Singular the Goods Chattles Rights & Credits which were of Francis Corbin, Esquire, deceased” for £600 “Proclamation Money which to him she owes” (approximately £450 sterling). On May 5, 1772, the Edenton District Superior Court awarded Kirshaw £211.6.[5] Although the nature of Corbin’s debt was not specified, the amount Kirshaw sought and received strongly suggests that he and his workforce were involved in the construction of the Cupola House.

With its central cupola, jetted second floor, soffit brackets, and steep front gable, the exterior of the Cupola House is clearly backward-looking in style for its time (fig. 3). The interior architectural details are more difficult to characterize. Although scholars have noted that the mantels resemble those in publications such as Colen Campbell’s Vitruvius Britannicus (London, 1715–1725) and William Salmon’s Palladio Londinensis (London, 1734), their compressed superstructure—occasionally seen on earlier examples—may have been dictated by the low ceiling height of the rooms (figs. 4, 5).[6]

As John Bivins observed, the carving on the mantels, stair brackets, and exterior elements is by the same hand.[7] In making such judgments, the first consideration is the craftsman’s drawing style, which in the case of the Cupola House carver consistently features leaves with broad, crowded, and awkwardly orientated lobes (figs. 6, 7). Judging from the simplistic design and execution of his work, the carver was likely a carpenter or joiner rather than someone trained as a carver or furniture maker. The crudely relieved ground around the stair bracket leafage broadcasts the carver’s lack of training and skill (fig. 8). Similarly, the modeling of the leaves on the brackets and mantel trusses (or consoles) is rudimentary, and shading is limited to one cut per lobe, qualities often seen in simple stone carving (figs. 6–8).

Jordan, Newbern, and Melchor assert that “architectural carving, especially that found on the exterior of a building, was often more two dimensional than . . . furniture carving because it was viewed from a distance,” but the opposite was usually the case.[8] Architectural ornaments intended to be viewed from considerable distance were typically high-relief and more three-dimensional than those positioned closer to the eye, but less detailed as far as complexity of outline, modeling, and shading are concerned. Interior details like mantel trusses, appliqués, and stair brackets are typically more highly detailed because they are viewed up close. As noted in Thomas Sheraton’s Cabinet Dictionary (1803):

Figures, foliage, and flowers are the three great subjects of carving; which, in the finishing, require a strength of delicacy suited to the height or distance of the object from the eye . . . . It requires some command of the mind, for the carver to work so close as to suit considerable height or distance; in which case, his eye, in working at so short a distance, must not govern him . . . but his judgement must take the lead, and constantly suggest to him the folly of finishing, in a tender manner, those flowers, and foliage . . . which are only to be viewed at a distance.[9]

Aside from differences in scale, the Cupola House carving shows almost no adjustment in “finishing” relative to “distance . . . from the eye.”

The Armchairs

The armchairs illustrated in figures 9–12 are among the earlier carved furniture from the Edenton area, and it is likely that the carver and maker were the same individual. The example illustrated in figure 9 is branded “JOHN COX / EDENTON NC” (fig. 13). Cox (1788–1856) was a later owner who operated a shipyard and brickyard in Edenton.[10] Juliana Harvey Elliott (1819–1879) donated a virtually identical armchair to Holy Trinity Episcopal Church in Hertford, North Carolina, in about 1870 (fig. 11).[11] Located in Perquimans County, Hertford is approximately thirteen miles northeast of Edenton. How John Cox and Juliana Elliott came into possession of their chairs remains unknown, but both were from local families. Two additional armchairs of the same design are known, but neither has an early history (figs. 10, 12).[12]

Bivins believed that these armchairs were from different sets, whereas Jordan, Newbern, and Melchor maintain that the chairs were from a single set of eight. Bivins cited the presence of different numbering systems, divergent wood use, and different seat coverings; however, the numbering is consistent on all of the surviving seating, wood use varies little from chair to chair, and only one chair has clear evidence of its original upholstery—a polychrome worsted wool (figs. 11, 14). The slip seat of another chair has two threads trapped under an original wrought nail, but it is impossible to determine if they are from the same fabric (figs. 10, 14). The “leather” identified by Bivins on the seat of the armchair illustrated in figure 9 is dark, deteriorated linen from the original foundation upholstery.[13]

The armchairs have Roman numerals on their front and rear rails and slip seats, three of which are from different chairs: II, III, IIII, IIIII, IIIIII, VII, and VIII (fig. 15). The absence of only one number in the sequence—I—is the strongest evidence both that these chairs are from the same set and that the set numbered at least eight chairs. The use of different woods (yellow pine and cypress) for glue blocks is not evidence to the contrary, since blocks of this type were often cut from scrap, and previous visual identification of one rear seat rail as being beech was incorrect. All of the known chairs have cherry rear rails.

The design and construction of the armchairs is consistent yet idiosyncratic, and it is through distinctive features that scholars segregate and group objects and identify patterns, origins, and occasionally makers. All of the chairs have carved crests; splats with scrolls, rosettes, and pierced strapwork that converges at the bottom center but not directly above; elaborately scrolled arms with carved rosettes and cyma-shaped supports (fig. 16); scalloped front seat rails; cabriole rear legs (fig. 17); and cabriole front legs with linear acanthus and claw-and-ball feet. As several furniture scholars have noted, the front legs are distinctive in being ovoid in cross section above the ankle and in having claw-and-ball feet with blade-shaped rear toes. The attachment of the arm supports to the seat rail is the most unconventional structural feature (fig. 18). Unlike many contemporaneous chairs—which have arm supports that are set in notches in the tops of the side rails, overlap at the sides, and are screwed in place from the inside—the arm supports of the examples illustrated in figures 9–12 rest on top of the rail moldings and are secured with a tenon and wrought sprigs (figs. 18, 19). The gap created by the arm supports not being set into notches or coped to fit around the rail moldings prompted the maker to insert filler strips.[14] The attachment of the arms to the rear stiles is more conventional (fig. 20). Each is set into a notch and secured with a single wooden pin. The knee blocks on the front legs are attached with glue and rose-head nails, the applied rear brackets are secured with glue and wrought sprigs, and the seat frame is reinforced with overlapping glue blocks (fig. 21). All of the knee blocks and the undersides of the rails have undercutting done with gouges (fig. 22).

As comparison of the crest rails suggests, the carving on the armchairs was laid out with patterns, which established the perimeter of the design and were essential in maintaining consistency from piece to piece (figs. 23, 24). However, the use of patterns did not require the carver to use the same tool for every corresponding cut. Variations in tool use are evident in the outlining, modeling, and shading on all of the armchairs. For speed and efficiency, carvers endeavored to use the tool they had in hand for as much work as possible before putting it down and retrieving another tool. And, in the production of sets of furniture, makers worked on one component at a time, which contributed to variations in tool use from object to object. This is evident in differences in the modeling and shading of the rosettes on the splats of the armchairs (fig. 25) as well as in other aspects of their carving, including the crest and knee leafage and claw-and-ball feet (figs. 23, 26–30).

Eighteenth-century carving tools were handmade and less uniform than those available today, and the evidence they left behind depended on how they were used and how they were sharpened. For example, some carvers had gouges with a slanted cutting edge to provide additional clearance; and some V-tools had slightly rounded bottoms, making it difficult to distinguish between a cut made by them and a cut made by a veiner. Carvers could also use different tools to achieve essentially the same results. The outline of a leaf that corresponds to a specific gouge sweep, for example, can be set in using a larger tool with an identical or similar sweep, with a V-tool, or by dragging a skew chisel. Determining the tools used to model carving is even more problematic because of the many ways a carver could go about hollowing concave surfaces and rounding convex ones, the latter often achieved by using back-bent gouges or conventional ones inverted.[15]

Paint, finish accumulation, wear, and aggressive refinishing can also make it difficult to determine precisely which tools carvers used and how they used them. For example, stippling is clearly visible around the central leaf cluster on the crests of two armchairs (figs. 9, 12, 23, 31) but not on the others. On the chair illustrated in figure 10, a dark, textured finish likely conceals the stippling, and on the example illustrated in figure 11, which underwent fairly aggressive “restoration,” the stippling may have been removed. Of the four surviving armchairs, the example illustrated in figures 12 and 31, has the best wood surface; the other chairs in the group have varying degrees of wear or abrasion, or obfuscating finish.

The carver of the armchairs was considerably more competent than the craftsman responsible for the exterior and interior ornaments of the Cupola House, but the former’s work is, as Bivins observed, somewhat “naïve” and “heavy handed.” In more conventional carving, the leaves on the front legs of the chairs would emanate from the scroll volutes on the knee blocks, but on the armchairs, the leaves flow from an arc above the volutes, and rows of chip cuts articulate the relieved area adjacent to them (figs. 26–28). The modeling of the leaves is coarse, displaying deep, irregular hollowing of the concave surfaces and poor regulation of the convex ones. As the details shown in figures 29 and 30 reveal, the carver of the armchairs was more adept in the production of claw-and-ball feet. The front and side toes have well-defined knuckles, and the ankle is sculpted to create the appearance of tendons. The blade-shaped rear toe, with prominent facets where it meets the ankle, is the most unusual aspect of this carver’s work. Similar rear toes also occur in the work of another local carver who, as Bivins and others have speculated, may have been a workman in the shop that produced the armchairs.[16]

In ascribing the armchairs to Samuel Black, Jordan, Melchor, and Newbern cite his presence in Edenton during the period when they believe that the seating was made, Black’s known production of armchairs, his workforce (which included apprentices and journeymen), and his patronage by Samuel Johnston (1733–1816) and other members of the local elite. Although all of those points are salient, both the text and biographical entries in Bivins’ monograph and recent research by historian Amber C. Albert document other craftsmen living in or near Edenton who could have produced mahogany furniture of comparable quality. John Rombough (d. 1778), for example, is recorded in Chowan County in 1747, and his 1778 probate inventory includes a large quantity of woodworking tools and a substantial amount of mahogany furniture, some of which he presumably had made. Rombough probably trained his son William (1758–1808), who took several apprentices and is also known to have made armchairs.[17] Bivins assigned a date range of 1745–1765 to the armchairs illustrated in figures 9–12, whereas furniture historian Adam Bowett agreed and further noted that 1745–1755 would be a more likely range if made for a fashionable setting in England.[18] If the chairs predate Black’s arrival in about 1758–1759, which is plausible, Rombough and Thomas Holt (d. ca. 1776) are candidates for their makers. Little is known about Holt aside from his taking John Pratt as an apprentice in 1736 and his decease in about 1776. In the apprenticeship document, Holt is described as being a “cabinetmaker” from Edenton.[19]

The presence of “8 Arm Mahogany Chairs” in the September 20, 1768, “Acct. Sales of the Estate of Francis Corbin Deceased” (see Appendix) is noteworthy owing to the rarity of documented sets of armchairs, but there is no conclusive evidence that the four surviving examples were his (fig. 32). Samuel Johnston purchased Corbin’s chairs for £8.15 (£1.1.10 each), a price that seems low for elaborately carved, cabriole leg armchairs. By comparison, Johnston paid £6.11 for “6 Walnut [side chairs] & 1 Smoking Chair” and £1.10 for “7 Walnut Chairs” (approximately 4s 3d each), forms made of less expensive wood and presumably of simple design.[20] Perquimans County cabinetmaker Thomas White’s account with Quaker merchant Thomas Newby provides a baseline for the cost of similar seating in eastern North Carolina around the date of Corbin’s sale. In January 1767, Newby owed White £15.4 for “12 Leather Chairs,” which may have resembled the example illustrated in figure 33. As was typically the case with earlier chairs exported to the Southern colonies from New England, White’s chairs were identified by their most readily recognizable feature: the upholstery material. At £1.5.8 each, those chairs were more expensive than the armchairs listed in Corbin’s sale. Indeed, the valuation assigned to Corbin’s chairs is more along the lines expected for armchairs with straight legs.[21] And, even if the armchairs illustrated in figures 9–12 were Corbin’s, his ownership is inconclusive in determining where, when, and by whom that seating was made.

Four legs from a table of undetermined form and a card table are by the carver of the armchairs (figs. 34, 35). The design of the knee carving is much the same as that of the chairs, differing primarily in not having a leaf that turns over at the bottom (fig. 36). The knee blocks on the card table are replaced, but the originals were glued and nailed, like those on the armchairs, and the undersides of its front and side rails are finished in a similar manner (fig. 37). One of the more distinctive features of the card table is the use of cherry for the fly rail and stationary leaf of the top and mahogany for the folding leaf, front and side rails, legs, and knee blocks. This relates to the use of cherry for the rear rails of the armchairs and mahogany for all other primary components.

Later Carved Furniture

Three card tables—two of which are a pair—and a writing table relate to the armchairs, most notably in having blade-shaped rear toes, yet they illustrate the work of another carver (figs. 38–41). The pair of card tables descended in the family of Willie Jones (1741–1801), whose father Robert Jones (1718–1766) and mother Sarah (Cobb) (ca. 1720–1757) lived at The Castle in Northampton County, North Carolina (figs. 38, 39). Born in Virginia and educated at Eton, the elder Jones moved to Northampton County in about 1750. He was a member of the Colonial Assembly, an agent for Lord Granville, and in 1756 served as the attorney general.[22]

Willie Jones was a prominent politician who managed a plantation of approximately ten thousand acres maintained by 120 enslaved workers. In 1801 he bequeathed a life interest in “all the looking glasses fixed & not fixed, the walnut chairs, mahogany & walnut Tables, Desks & Book Cases & Beaufats which belong to my Halifax House together with the side Boards” to his wife, Mary (Montfort) Jones (1760–1825), and then to his eldest son, Willie W. Jones (1784–1838) and his heirs. The estate inventory for Mrs. Jones lists “3 card tables,” while that of her son, who died unmarried and without children, lists “2 Card Tables” in the downstairs chamber and an additional card table in the “old room up Stairs” at The Grove, outside of Halifax.[23] Based on the birth and death dates of Willie Sr. and his father, either could have been the original owner of the pair of tables.

The card table illustrated in figure 40 does not have an early history, but the writing table likely descended in the Blount, Benbury, and Cullens families of Perquimans County and Chowan County, North Carolina (fig. 41). The table probably entered the Cullen family after Mary Benbury’s (b. 1835) marriage to Nathan L. Cullen (1830–1900) in Chowan County on May 4, 1854. Mary was the daughter of William and Sarah (Norcom) Benbury, whose ancestors were among Edenton’s wealthier residents. The probate inventory of Mary’s great-grandfather, Edmund Blount (1745–1792), includes “one Mahogany Dressing Table,” purchased for two pounds in 1793 by his widow Mary (d. 1811) and described as “1 mahogany dressing table & glass.” The upper drawers of writing tables and dressing tables were outfitted in much the same manner, often making it difficult for later appraisers to correctly identify certain examples of those forms. Edmund Blount and Mary Hoskins were married on February 26, 1765, a plausible date for the production of this table.[24]

The knee carving on the writing table and later card tables consists of a central husk suspended from a small, three-petal flower, larger three-petal flowers on either side, and linear leafage below (fig. 42). Unlike the leafage on the armchairs and earlier card table, that on the later tables emanates from the scroll volutes in a conventional manner (fig. 43). The later tables carver’s leafage also displays superior modeling of the convex and concave surfaces and more controlled shading, all done with a veiner rather than a veiner and a V-tool as on the knees of the armchairs. His claw-and-ball feet also differ from those of the armchairs in having webbing, more definition of the knuckles and tendons, thinner rear toes that lack facets at the top, and more compressed balls (figs. 44, 45). Jordan, Newbern, and Melchor attempt to rationalize these differences by positing that the carver of the chairs may have begun producing different feet after seeing those on an imported chair.[25] That speculation runs counter to surviving evidence, which indicates that carvers rarely deviated from their work methods—which were deeply imprinted by training and repetition—even when mimicking another’s work.[26]

Similarly, the authors’ assertion that the leg pattern used for the armchairs was the same one used for the later tables is misleading because the templates they illustrate could be used to create sawn blanks for many different leg designs. More importantly, the construction of the later card tables differs from that of the early example in several ways (figs. 37, 46): their knee blocks overlap the rails rather than being attached under them; their primary rail stock is thicker and undercut differently; their inner rear rails and fly rails are red oak and walnut respectively, rather than yellow pine and cherry; their inner rear rail extends below their outer rear/fly rail rather than being flush with it; and the knuckle joints of their fly rails are thinner and have seven segments instead of five. One structural feature shared by the early card table and three later ones is the shape of their knuckle-joint segments, which are much flatter than normal and have unusually shallow clearance cuts for stopping the fly rail at ninety degrees when extended (fig. 47). It is possible that at least one craftsman in the shop that produced the later tables worked in the shop responsible for the armchairs and early card table, as Bivins and others have suggested; however, the differences discussed above point to two separate shops.

Horton and Bivins attributed the stair brackets and landing frieze from the George Blair House to the carver of the later card tables and writing table, noting the use of chip cuts, stippled grounds, strapwork borders, and leafage emanating from small flowers (figs. 48, 49).[27] Furniture scholar Wallace Gusler disagreed. In his monograph The Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710–1790, Gusler wrote:

While . . . these carvings have punched grounds and make use of a . . . border in some areas, they have quite different approaches to design and divergent techniques . . . . The fascia board and stair brackets from the Blair–Pollock House have sinuous entwining vines ending with very small volutes or narrow leaves, and reflect the spirit of baroque design from the seventeenth century. Many of the leaves and tendrils have busy details formed by gouge cuts, made by driving a gouge at a right angle into the wood. A second cut was made converging with the first, thereby removing a small plug. The carving on the furniture does not utilize the profuse gouge marks and, with the exception of a few veins in each leaf, is characterized by large, plain rounded surfaces. The leaves are much broader and differ completely from the design of those on the architectural elements of the Blair-Pollock House.[28]

Gusler was correct in his observations regarding differences in design and technique, including the profusion of chip cuts on the architectural carving and the limited use of them on the furniture leafage.[29] Moreover, differences in the scale of the furniture and architectural carving, and a thick accumulation of paint on the latter, make it virtually impossible to determine if this work represents one or two, possibly related, hands. If contemporaneous, as seems likely, the later card tables and writing table probably date to 1760–1775. George Blair (1738–1772) arrived in Edenton around 1756, married Jean Duncan Johnston (sister of Samuel Johnston) (1740–1789) in 1762, and purchased a town lot the following year. Construction of the couple’s house probably began soon after and was completed before 1769, when the building was designated on C. J. Sauthier’s A PLAN of the Town & Port of EDENTON in Chowan County NORTH CAROLINA. Blair was a partner in the mercantile firm Blount, Hewes, and Blair, and his day book for the years 1771–1772 documents business with local craftsmen including John Rombough and Alexander Montgomery.[30]

A Flawed Methodology

The methodology Jordan, Melchor, and Newbern use to construct their argument that the Cupola House carver was responsible for the aforementioned furniture work is fundamentally flawed. The tools they cite as being used for this architectural and furniture carving were present in the kits of many of their contemporaries, who used them for outlining, modeling, and shading in much the same way; and, as noted above, different tools can be used to establish outlines and model surfaces that appear visually the same. The authors’ illustrations showing gouges adjacent to carving in the Cupola House and on components of a reproduction chair are also misleading, as similar correlations could easily be demonstrated on many examples of colonial carving, and in some instances, the tool they show was not the only one that could have been used for the purpose suggested. This is apparent in one illustration wherein a gouge is placed adjacent to the lobe of a leaf on a mantle truss, implying that a vertical cut with that specific tool was used to outline that portion of the design (fig. 50). Although the gouge sweep aligns with part of the curve, the lobe could have been outlined in its entirety with a single cut made with a larger gouge of the same sweep or with multiple cuts with a smaller gouge of the same sweep. Considerable build-up of paint on the truss makes specific tool identification problematic. The disturbed area of the finish at the top of a leaf from one of the stair brackets in the Cupola House indicates where the authors placed the gouge they maintain was responsible for outlining the top and underside of that lobe (fig. 51). However, the carver could have used other gouges of the same sweep. Moreover, the underside of the lobe was more likely outlined with a V-tool (possibly the same tool used to make the shading cut in the middle of the lobe) or by dragging a skew chisel.

Further evidence of Jordan, Newbern, and Melchor’s flawed approach can be seen in their more recent essay “Cupola House Tea Table,” which states that the subject object (fig. 52) is “proven to be by [Samuel] Black based on the use of three of his ten gouges,” and that it was part of a 1758 commission from Corbin that included the eight armchairs listed in the account of his sale.[31] The authors’ thesis is completely conjectural. Evidence for the use of imperial-system equivalents of the gouges they cite can be found on many tea tables with scalloped, edge-molded tops, and there is no known documentation that Corbin commissioned furniture from Samuel Black, either in 1758 or at any other time prior to the former’s death. Even more over-reaching is the authors’ assertion that the chairs and tea table were part of the same commission because the arms of the former and work surface of the latter are more or less the same height.[32]

As evidence of the table’s local production, the authors cite the sharp, tapering of the underside of the ankle as it transitions to the ball, which they liken to the blade-shaped rear toes of the armchairs, early tables, and later tables. That comparison is inconsequential since similar transitions can be found on pillar-and-claw stands and tables from other areas of the colonies, and the transition on the subject table bears no relationship to the carving of the rear toes of locally made furniture.[33] Similarly, the use of a box birdcage is insufficient to attribute the tea table to Edenton, as similar birdcages occur on examples from England and New York. Indeed, there is no conclusive evidence that the so-called “Cupola House table” was even made in Edenton. A more likely candidate for original ownership by Corbin is shown in figure 53. That table descended in the family of Samuel Johnston, who paid two pounds for a “Round [Mahogany] Tea Table” at Corbin’s sale.[34]

By focusing almost solely on their interpretation of tool use, Jordan, Melchor, and Newbern fail to consider adequately the importance of design, habit, and proficiency when evaluating carving. Their approach is analogous to assessing furniture produced with two similar tool kits without giving appropriate thought to way the furniture looks, how the components are assembled, and the level of competency displayed in the final products. The carving in the Cupola House, on the early armchairs and card table, and on the later tables diverges significantly because those responsible drew and laid out their work differently, had different work habits, and attained significantly different levels of proficiency. In sum, the furniture illustrated and discussed here was carved by two different hands, neither of which is present in work from the Cupola House.[35]

Conclusion

Responsible scholarship requires clear distinctions among opinion, speculation, and fact, as well as avoidance of overstatements and circular logic like that found in The Cupola House Carver and “Cupola House Tea Table,” examples of which are cited below.

• “Evidence points to Samuel Black having arrived in Edenton from Great Britain in 1758 or early 1759, but his exact origins are unknown at this point.” Samuel Blake (likely Black) appears on the Chowan County tax rolls in 1758 and Samuel Black in 1759. The inference that he emigrated from the British Isles is based on the design of the armchairs, which have not been linked to him definitively.

• “A craftsman of Black’s skills was well prepared to produce furniture of the level of the Edenton carved group.” The authors infer a level of skill from furniture they attribute to Black. Without knowing where and with whom Black trained, or precisely what he and his workmen produced, assumptions about his skill level are speculative.

• “The four . . . Edenton armchairs are undoubtedly the remaining members of the set . . . listed in Corbin’s estate inventory and were made for and began life in the dining room of the Cupola House.” Despite the authors’ use of the adverb “undoubtedly,” there is no conclusive evidence that the surviving armchairs were those listed in the account of Corbin’s sale.

• “There is no evidence of any Edenton craftsmen, predating Black’s arrival in 1758, producing work that predates the construction of the Cupola House with any similarity to the carving at the Cupola House and the carved Edenton furniture group.” It is impossible to extrapolate positive evidence from something that does not exist. However, it is possible that the armchairs were made by another craftsman prior to or after Samuel Black’s first known appearance in local records.

• “The date of the construction of the eight mahogany armchairs . . . had been established based on the same exact nine tools being used in their construction as well as the Cupola House carving.” The date of the construction of the armchairs is based on the erroneous conclusion that they were carved by the hand responsible for the ornaments in the Cupola House. Moreover, tool use provides no evidence of date.

• “Compelling evidence points to Samuel Black as the only logical candidate in Edenton to have made these chairs and other members of the carved Edenton furniture group, along with elements in the Cupola House and the George Blair House.” Black and members of his workforce are candidates for makers of part or all of the carved furniture in the Edenton groups, but it is an overstatement to claim that they were the only logical possibilities. Bivins and Albert have identified other possible makers, and there is no reason to believe that the surviving historic records include the names of all furniture makers who worked contemporaneously in the area.[36]

• “This [the so-called ‘Cupola House tea table’] is the only example of a round tea table of the mid-eighteenth-century displaying ball and claw feet and a piecrust top that can be shown conclusively to have been made . . . in Edenton. Its quality is also consistent with the quality of the one round mahogany tea table sold from the dining room at Corbin’s . . . estate sale, based on the price it fetched.” Attribution of the table to Edenton is based on a flawed methodology for assessing carving and on stylistic details—a box birdcage and sharp underside of the ankles where they transition to the feet—that are more generic than the authors claim. Without knowing the appearance of Corbin’s tea table, it is impossible to determine if it and the so-called “Cupola House table” were of comparable “quality.”

• “The matching height of Mr. Black’s armchair arms and the height of Mr. Black’s round tea table . . . is not a coincidence. He intentionally constructed this tea table to match with Corbin’s eight armchairs.” Referring to the armchairs and tea table as “Mr. Black’s” and asserting that they are from the same commission as the armchairs is unwarranted by the physical evidence and lacks any supporting documentation.

Shortcomings of this sort diminish the work Jordan, Newbern, and Melchor have done in expanding the biographies of Samuel Black and his workmen and in shedding light on patronage in northeast North Carolina during the last half of the eighteenth century. The biographies alone position those craftsmen as strong candidates for the production and ornamentation of the carved furniture discussed above. With independent editorial oversight and peer review from other scholars—particularly those whose focus is Southern furniture and colonial carving—the problematic aspects of Jordan, Newbern, and Melchor’s work could have been identified and resolved, leaving scholarship that better reflected the intentions and goals of those authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS For assistance with this article, the author thanks Daniel Ackermann, Amber Albert, Gary Albert, Gavin Ashworth, Tara Chicirda, Leroy Graves, Ralph Harvard, Matt Hobbs, Neal Hurst, Ron Hurst, Robert Leath, Alan Miller, Sumpter Priddy, Jon Prown, and the institutional and private owners who kindly provided access to the objects illustrated and discussed here.

“Acct. Sales of the Estate of Francis Corbin Deceased” See (figs. 54-60)

Frank L. Horton, “Carved Furniture of the Albemarle: A Tie with Architecture,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts (hereafter JESDA) 1, no. 1 (May 1975): 14–20, available online at archive.org/details/journalofearlyso11muse/page/16/mode/2up.

John Bivins Jr., The Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, 1700–1820 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, 1988), pp. 154–71.

Don Jordan, Tom Newbern, and Jim Melchor, The Cupola House Carver (Edenton, N.C.: Elizabeth Van Moore Foundation, 2021). “The Cupola House Carver” was initially published in two installments in 2021 on the Edenton Historical Commission (North Carolina) website, https://ehcnc.org/decorative-arts/furniture/. For the tea table essay, titled “Coupola House Tea Table,” see Edenton Historical Commission (N.C.) website, https://ehcnc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/CH-Tea-Table.pdf. There are several problematic essays in the furniture section of the Edenton Historical Commission website, most notably those that continue to attribute furniture made by the “WH cabinetmaker” (see Bivins, Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, pp. 291–322) to William Seay. The basis for the Seay attribution was refuted by F. Carey Howlett and Kathy Z. Gillis in “Scientific Imaging Techniques and New Insights on the WH Cabinetmaker: A Southern Mystery Continues,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2013), pp. 71–100, and subsequent essays promoting the Seay attribution are unconvincing. Some scholars have suggested that the armchairs illustrated in figs. 10–13 and other carved furniture shown and discussed here may have been made in Norfolk, Virginia, which is located approximately seventy miles to the north and was accessible by land around the Dismal Swamp and via the Blackwater or Northwest Rivers, which lead to the Elizabeth and Nansemond Rivers. Wealthy planters and other members of the elite in northeastern North Carolina did considerable business in Norfolk and other Hampton Roads ports. Much of the lumber, naval stores, pork, and corn exported from that part of Virginia came from eastern North Carolina (see Thomas Costa, “Economic Development and Political Authority: Norfolk, Virginia Merchant-Magistrates, 1736-1800” [Ph.D. diss., College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Va., 1991], pp. 25–28, available online at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/235413989.pdf). Given those economic and social ties, one would expect that Norfolk furniture made its way into North Carolina households, just as furniture made in Boston was shipped to New York and other New England colonies in the eighteenth century. Norfolk or its environs cannot be excluded as the place of origin for all or part of the “Edenton Group,” but the preponderance of evidence currently suggests that the furniture was made in or near Edenton. While doing research for this article, the author personally inspected every object discussed here except the fragmentary table illustrated in fig. 34.

Heikkenen’s study is discussed in Thomas R. Butchko, Edenton, An Architectural Portrait (Edenton, N.C.: Edenton Woman’s Club and Chowan County Government, 1992) and cited online at https://www.chowancounty-nc.gov/index.asp?Type=B_BASIC&SEC=%7BC678AE3E-0A3B-4625-BF00-B2CE7F001780%7D&DE=%7B54337FF5-C286-4EF5-9626-C069767E477C%7D. For earlier dating, see Bruce S. Cheeseman, “The Cupola House of Edenton, Chowan County,” 3 vols. (historical research report, North Carolina Division of Archives and History, Raleigh, N.D., 1980), 1: 1–46, available online at https://digital.ncdcr.gov/Documents/Detail/cupola-house-of-edenton-chowan-county-vol.-1/753082?item=753157; ———, “The Survival of the Cupola House: ‘A Venerable old Mansion,’” North Carolina Historical Review 63, no. 1 (January 1986): 40–73; Bruce S. Cheeseman (with added comments and illustrations by John Bivins Jr.), “The History of the Cupola House, 1724-1777,” JESDA 15, no.1 (May 1989): 1–57; and John Bivins Jr., James Melchor, Marilyn Melchor, and Richard Parsons, “The Cupola House: An Anachronism of Style and Technology,” JESDA 15, no.1 (May 1989): 57–177, available online at https://archive.org/details/journalofearlyso1511989muse/mode/2up.

Bruce S. Cheeseman, Catherine W. Bishir, and Felicity Smith, “Kirshaw Robert (fl. 1740s–1772),” 2012, North Carolina Architects and Builders: A Biographical Dictionary, NC State University Libraries, Raleigh, N.C., available at https://ncarchitects.lib.ncsu.edu/people/P000523. For more on North Carolina currency, see Cory Cutsail and Farley Grubb, “The Paper Money of Colonial North Carolina, 1712–74: Reconstructing the Evidence” (working paper, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Mass., 2018), esp. p. 1, available online at https://www.nber.org/papers/w23783.

The author thanks architectural historian Ralph Harvard for this suggestion.

Bivins, Melchor, Melchor, and Parsons,“The Cupola House: An Anachronism,” p. 93.

Jordan, Newbern, and Melchor, The Cupola House Carver, p. 68.

Thomas Sheraton, The Cabinet Dictionary: Containing an Explanation of All the Terms Used in the Cabinet, Chair and Upholstery Branches (London, 1803), p. 135.

Jean Fagan Yellin, The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), p. 49, note 15.

The history of the chair donated to the Holy Trinity Episcopal Church is recorded in object file S-1588 and accession file 2418, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (hereafter cited as MESDA), Winston-Salem, N.C. See also https://mesda.org/item/collections/arm-chair/262/, which notes that “Mrs. Elliott’s great-grandfather, Benjamin Harvey (1727–1774), was a wealthy planter and politician who represented Perquimans in the North Carolina colonial assembly” and speculates that the armchair illustrated in fig. 12 may be the “Mahogany Arm Chair” listed in the probate inventory of [her] . . . uncle and guardian, Thomas Harvey (d. 1844), of Pasquotank County.”

The author purchased the armchair illustrated in fig. 12 when he was executive director of the Chipstone Foundation (Important Americana [New York: Sotheby’s, October 9, 1997], lot 503). The foundation subsequently deaccessioned the chair, and it is currently in a private collection.

Bivins, Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, p. 159. Jordan, Newbern, and Melchor, The Cupola House Carver, p. 159.

Neither Bivins nor Jordan, Newbern, and Melchor made note of the unusual attachment of the arm supports to the side rails.

The author thanks furniture scholar Alan Miller and blacksmith and scholar Peter Ross for their thoughts on the manufacture of eighteenth-century carving tools.

Bivins, Melchor, Melchor, and Parsons,“The Cupola House: An Anachronism,” pp. 156, 160. Bivins, Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, pp. 155–77. Two dining tables have claw-and-ball feet with blade-shaped rear toes similar to those on the later card tables and writing table. For the dining tables, see Bivins, Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, pp. 168–71.

Amber C. Albert, “Edenton Cabinetmakers,” available at https://chipstone.org/content.php/77/Edenton-Cabinetmakers; for Rombough, see Bivins, Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, pp. 171, 496, 497.

Adam Bowett to Luke Beckerdite, personal email communication, November 21, 2022.

For Holt, see Bivins, Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, p. 475. Alexander Montgomery is identified as a cabinetmaker in a deed dated June 9, 1773, but he may have been working in Chowan County earlier. He died in 1778, and his estate inventory includes 37 looking glasses, 48 looking glasses without frames, a mahogany fiddle case, “1 Sett Cabinet Makers Tools,” a set of turning tools, “2 Sett Desk furniture,” a diamond for cutting glass, and 100 feet of mahogany. Among his household furnishings were a clock, a chest of drawers, a mahogany tea table, a teaboard and two waiters, and a “beaufett” (ibid., p. 478).

Estate Records of Francis Corbin, 1768, Cupola House Papers, 1744-1834, Chowan County Miscellaneous Records, CR.024.928.40, State Archives of North Carolina, Raleigh. On July 22, 1768, the Virginia Gazette reported, “to be SOLD at public vendue, for ready money, at the late dwelling house of Francis Corbin, Esq., deceased, on Tuesday the 20th of September next, ALL THE HOUSEHOLD & KITCHEN furniture of the said Francis Corbin; also a valuable collection of books; and sundry very likely country born SLAVES.” One of Edenton’s wealthier and more prominent citizens, Johnston was the principal buyer at Corbin’s sale. Among his many purchases were a pair of large looking glasses for £12.0.6, “2 square Mahogany Tables” for £4, a round mahogany tea table for £2, “1 Bed & Furniture” for £9, a dressing table for £3, a dressing glass for £1, several books, and an assortment of “china,” glass, and metal wares. The prices realized suggest that there was considerable competition among those who attended the sale.

The September 5, 1768, inventory of Norfolk, Virginia, merchant Robert Tucker’s estate lists “12 Mahogany chairs” valued at £6 and five “Mahogany chairs” valued at £5; the January 1, 1768, inventory of the personal effects of William Webb of Richmond, Virginia, lists 12 “mahogany leather bottom chairs” valued at £9. For Tucker, see “Tucker, Robert,” Probing the Past: Probate Inventories, 1740–1810, Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Medium, George Mason University and Gunston Hall Plantation, https://chnm.gmu.edu/probateinventory/document.php%3FestateID=288.html; for Webb, see “Webb, William,” Probing the Past: Probate Inventories, 1740–1810, https://chnm.gmu.edu/probateinventory/document.php%3FestateID=303.html. The Webb and Tucker valuations are in Virginia currency, wherein £1VA = £1.25 sterling: Grubb, “Colonial Virginia’s Paper Money Regime, 1755-1774: A Forensic Accounting Reconstruction of the Data” (working paper, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, Mass., 2015), p. 28, available online at https://nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w21785/w21785.pdf. The author thanks furniture historian Matt Hobbs for the reference to Newby’s purchase and for his thoughts on the side chair illustrated in fig. 33. See also, John Bivins, “Rhode Island Influence in the Work of Two North Carolina Cabinetmakers,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Lebanon, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1999), p. 84. Much of the new research on White presented in Bivins’ article was done by Hobbs. Presumably, all of the prices in the account of Corbin’s sale and White’s bill were in North Carolina proclamation money. The exchange rate in 1768 was £1 sterling = £1.33 NC (Cutsail and Grubb, “The Paper Money of Colonial North Carolina,” p. 1).

For more on Willie Jones, see Robinson P. Blackwell, “Jones, Willie,” 1988, NCpedia, https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/jones-willie. For Robert, see James P. Beckworth Jr., “Jones, Robert (“Robin”) Jr.,” https://www.ncpedia.org/biography/jones-robert-robin-jr. For the history of the card tables, see the MESDA Collections Database, https://mesda.org/item/collections/card-table/328/.

For the probate information, see MESDA Collections Database, https://mesda.org/item/collections/card-table/328/.

For more on the history and probable line of descent of the writing table, see MESDA Collections Database, https://mesda.org/item/collections/dressing-table/459/.

Jordan, Newbern, and Melchor, The Cupola House Carver, p. 21.

Luke Beckerdite, “The Concept of Copying in the Eighteenth-Century Carving Trade,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Haverton, Pa.: Casemate Publications/Oxbow Books for the Chipstone Foundation, 2020), pp. 90–119.

Horton, “Carved Furniture of the Albemarle,” pp. 14–20; Bivins, Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, pp. 163–64.

Wallace Gusler, The Furniture of Williamsburg and Eastern Virginia, 1710–1790 (Richmond, Va.: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 1979), p. 157, note 7.

Although unconventional, the use of chip cuts to articulate the convex and concave surfaces of leaves occurred contemporaneously in furniture carving from other areas of the colonies, including Charleston, South Carolina.

For the history of the Blair House, see “Passage” and “Parlor,” MESDA Collections Database, https://mesda.org/item/collections/passage/1686/ and https://mesda.org/item/collections/parlor/1687/; and Bivins, Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, p. 163. For Sauthier’s map, see “Port of Edenton in Chowan County North Carolina,” Norman B. Leventhal Map and Education Center, Digital Collections, Boston Public Library, https://collections.leventhalmap.org/search/commonwealth:hx11z435c. For the day book, see Bivins, Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, p. 171.

See Jordan, Newbern, and Melchor, “Cupola House Tea Table,” https://ehcnc.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/CH-Tea-Table.pdf.

As in The Cupola House Carver, Jordan, Newbern, and Melchor’s essay on the tea table includes illustrations showing how they believe the gouges they cite were used. The image related to the carving of the webbing is particularly misleading, as the concave surfaces are clearly too abraded to determine tool use.

For similar transitions see “Table, Tea [misattributed to Newbern, N.C.],” MESDA Collections Database, https://mesda.org/collection/object/?mpq=&mpf1=&mpf2=&mpf3=&mpf5=&mpf4=S-4962; and a related tea table in the collection of the Chipstone Foundation, “Tea table,” Collections: Furniture, Chipstone Foundation (database), http://chipstone.dom5183.com/objects-1/info?query=Portfolios%20%3D%20%2239%22&sort=0&page=59.

Bivins, Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, p. 153; “Acct. Sales of the Estate of Francis Corbin Deceased,” p. 1 (see Appendix).

For studies of carving based on design, technique, proficiency, and historical context, see Luke Beckerdite, “William Buckland Reconsidered: Architectural Carving in Chesapeake Maryland, 1771–1774,” JESDA 8, no. 2 (November 1982): 6–41; ———, “William Buckland and William Bernard Sears: The Designer and the Carver,” JESDA 8, no. 2 (November 1982): 42–88; ———, “Philadelphia Carving Shops. Part I: James Reynolds,” Antiques 125, no. 1 (May 1984): 1120–1133; ———, “Philadelphia Carving Shops. Part II: Bernard and Jugiez,” Antiques 128, no. 3 (September 1985): 498–513; John Bivins Jr. “Charleston Rococo Interiors, 1765–1775: The ‘Sommers’ Carver,” JESDA 12, no. 2 (November 1986): iv–129, available online at https://archive.org/details/journalofearlyso1221986muse/page/n5/mode/2up; Luke Beckerdite, “Carving Practices in Eighteenth-Century Boston,” in Old-Time New England, New England Furniture: Essays in Memory of Benno M. Forman 72, no. 259 (Boston: Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, 1987): 123–162; ———, “Philadelphia Carving Shops. Part III: Hercules Courtenay,” Antiques 131, no. 5 (May 1987): 1044–1063; ———, “Origins of the Rococo Style in New York Furniture and Interior Architecture,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1993), pp. 15 –37; ———, “Architect-Designed Furniture in Eighteenth-Century Virginia: The Work of William Buckland and William Bernard Sears,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H. and London: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1994), pp. 29–48; ———, “Immigrant Carvers and the Development of the Rococo Style in New York, 1750–1775,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 1996), pp. 233–265; Luke Beckerdite (written for John Bivins Jr.), “Early Carving in the South Carolina Low Country: The Career and Work of Henry Burnett,” edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2003), pp. 2–26; Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller, “A Table’s Tale: Craft, Art, and Opportunity in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004), pp. 2–45; Luke Beckerdite, “Pattern Carving in Eighteenth-Century Philadelphia,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2014), pp. 86–141; Luke Beckerdite and Margaret K. Hofer, “Stephen Dwight Reconsidered,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2016), pp. 146–164; Luke Beckerdite and Alan Miller, “A Philadelphia-Carved Bust of Benjamin Franklin,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2016), pp. 2 –22; Luke Beckerdite, “Thomas Johnston, Hercules Courtenay, and the Dissemination of London Rococo Style,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2016), pp. 23–61; ———, “Brian Wilkinson, Samuel Harding, and Philadelphia Carving in the Early Georgian Style,” in American Furniture, edited by Luke Beckerdite (Haverton, Pa.: Casemate Publications/Oxbow Books for the Chipstone Foundation, 2020), pp. 120–165; and ———, “The Concept of Copying in the Eighteenth-Century Carving Trade,” pp. 90–119.

Bivins, Furniture of Coastal North Carolina, pp. 171, 456, 475, 487, 496, 497; Albert, “Edenton Cabinetmakers.”