The Ropes Mansion, 318 Essex Street, Salem, Massachusetts. Unknown photographer, ca. 1890. (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum [Ropes Papers, box 21, folder 2].) This photograph shows the site of Mark Pitman’s cabinetmaking shop on the left side of the house with the board fence erected in the 1850s.

Desk and bookcase, labeled by Mark Pitman (1779–1855), Salem, Massachusetts, 1807–1812. Mahogany, pine, glass. H. 67 1/2", W. 41 7/8", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, given in honor of Dean Lahikainen and in memory of Anna Sterns by Anna Thurber, 2018.31.1AB; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the printed label of Mark Pitman inside the desk and bookcase in fig. 2. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Printed label with Mark Pitman’s handwritten signature pasted over the name of Josiah Caldwell. (Location unknown; photo, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.) Illustration from Dean A. Fales, Essex County Furniture: Documented Treasures from Local Collections, 1660–1860 (Salem, Mass.: Essex Institute, 1965), pl. 33.

William Bache (1771–1845), Silhouette of Elizabeth (Cleveland) Ropes (1757–1831), stamped “Bache’s Patent,” 1805. Cut paper and chalk. H. 5 3/8". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R905.1.)

Detail of Henry McIntyre, A Map of the City of Salem, Mass. (Philadelphia, 1851). (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.) The map shows the two shop buildings at 324 Essex Street next to the Ropes Mansion, marked “Mrs. Orne.”

Traveling desk by Mark Pitman, 1812. Mahogany, pine, glass, baize, brass, metal. H. 6 1/2", W. 20", D. 10". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1129.)

Medicine chest by Mark Pitman, ca. 1807–1830. Painted pine, metal. H. 8 1/4", W. 13", D. 9 1/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1290; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Medicine chest containing sixteen glass bottles (ten labeled) with mixing and measuring equipment, British, 1820–1850. Mahogany, glass, brass, velvet. (Courtesy, Science Museum Group, Sir Henry Wellcome’s Museum Collection, A173654, © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum.)

Sewing box, attributed to Mark Pitman, ca. 1807–1836, with painted decoration possibly by Sally (Ropes) Orne (1795–1876) or Elizabth Ropes Orne (1818–1842). Maple or birch, pine, paper. H. 1 7/8", W. 3 1/2", D. 3 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1250.)

Detail of the painted decoration on the top of the box in fig. 10.

Work table by Mark Pitman, 1810–1825, with painted decoration attributed to Elizabeth Ropes Orne (1818–1842), possibly in association with James A. Cleveland (1811–1868), 1830s. Bird’s-eye maple, mahogany, glass, brass. H. 30", W. 21 3/4", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1119; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the painted decoration on the top of the table in fig. 12. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the painted decoration on the front of the table in fig. 12. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the painted decoration on the right side of the table in fig. 12. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the painted decoration on the left side of the table in fig. 12. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Elizabeth Ropes Orne, Sketch of a bridge, 1830s. Graphite on paper. H. 3 1/4", W. 5 3/4" (approx.). (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum [Ropes Papers, box 10, folder 4].)

Detail of a sketch by James A. Cleveland, 1830s. Graphite on paper. H. 4 1/2", W. 7 3/4" (approx.). (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum [Ropes Papers, box 10, folder 4].)

Sketch by James A. Cleveland in Elizabeth Ropes Orne’s autograph book, 1839. Graphite on paper. H. 2 1/4", W. 5 1/2" (approx.). (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum [Ropes Papers, box 10, folder 10].) The inscription reads: “Drawn by J. Cleveland.”

Sketch shown on plate 7 in James Arthur Cleveland’s The Elements of Landscape Drawing (Cincinnati, 1839). Lithograph on paper. H. 9 1/2", W. 12". (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1954, 54.524.76; photo, Art Resource NY.)

Detail of the painted decoration on the back of the table in fig. 12. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Samuel Finley Breese Morse(1791–1872), Mrs. Joseph Orne (Sarah “Sally” Ropes), 1817. Oil on board. H. 15 1/2", W. 13 1/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R744.)

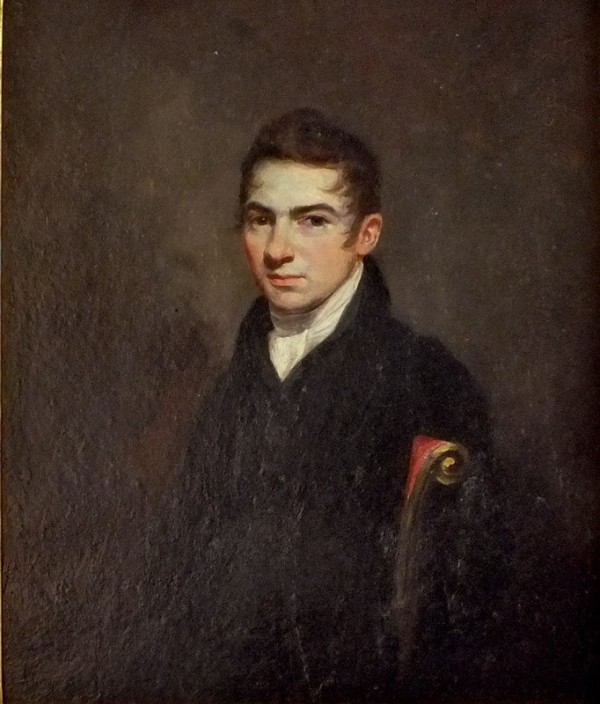

Samuel Finley Breese Morse(1791–1872), Joseph Orne, 1817. Oil on board. H. 15 1/2", W. 13 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R745.)

Detail of a photograph of the Capt. William Orne House, Washington Street, Salem, Massachusetts, attributed to Daniel A. Clifford, ca. 1855. (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.) The house was designed by Samuel McIntire (1757–1811) in 1795 and was the home of Sally and Joseph Orne from 1817 to 1819.

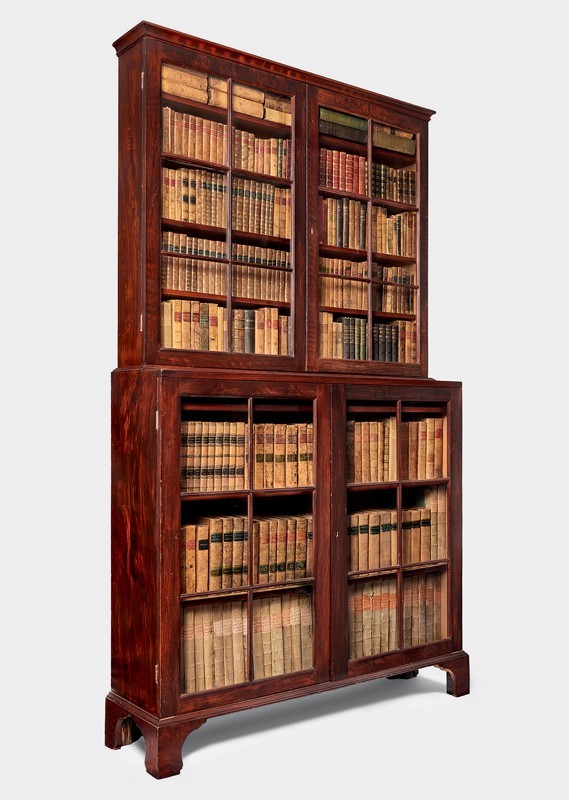

Set of bookcases by Mark Pitman, 1816. Pine (grain-painted to simulate mahogany or rosewood), glass, metal. H. 89 1/2", W. 50 1/4", D. 14". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1075; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

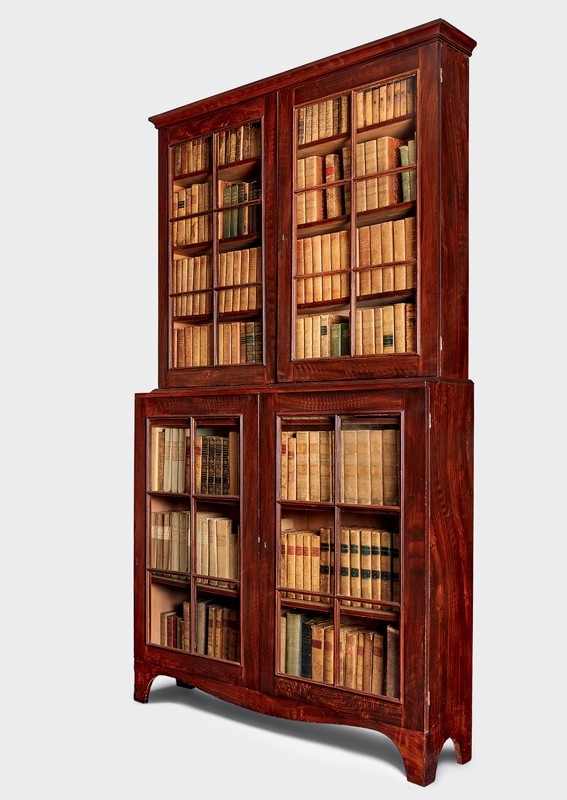

Set of bookcases by Mark Pitman, 1818–1830s. Pine (grain-painted to simulate mahogany or rosewood), glass, metal. H. 89", W. 50", D. 12". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1076; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

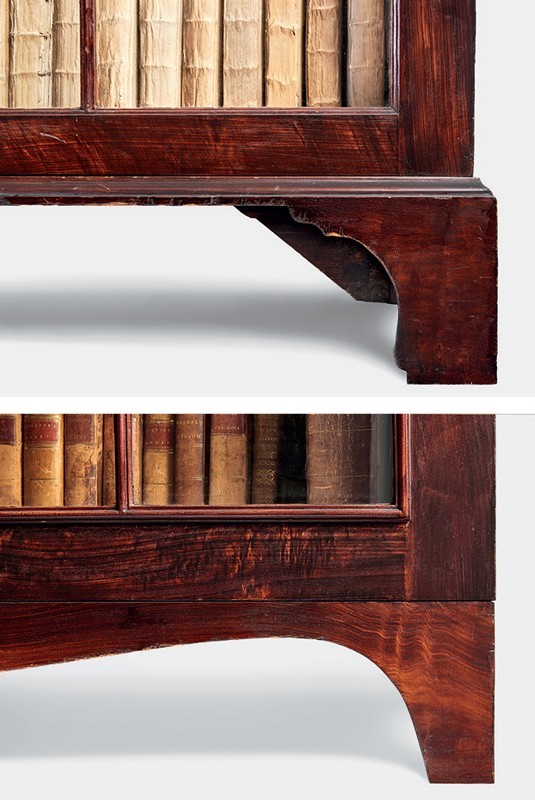

Detail of the bracket foot, base molding, and stiles and rails on the glass door on the bookcase in fig. 25 (above); detail of the shaped skirt and bracket foot on the bookcase in fig. 26 (below). (Photos, Michael E. Myers.)

Receipt for Capt. Jonathan Hodges from Mark Pitman, April 8, 1808, for furniture supplied for the marriage of his daughter, Elizabeth H. Hodges, to George Cleveland of Salem. (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum [Hodges Family Papers, box 22, folder 17].)

Bedstead with painted cornice by Mark Pitman, 1816–1817. Mahogany, maple, painted pine, brass, metal, with canvas, rope, and reproduction chintz. H. 90 7/8", W. 60 1/4", D. 78 3/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1104; photo, Dennis Helmar.) The bedstead was made for the wedding of Joseph and Sally (Ropes) Orne. The hangings were added in 2015 using a reproduction of the original chintz fabric (see fig. 33).

Postcard, 1950s. Printed paper. H. 3 1/2", W. 5". (Collection of the author.) This image of the Peabody Museum of Salem’s 1950s recreation of the bedroom on Cleopatra’s Barge shows the painted bedstead commissioned for the yacht by George Crowninshield. The hangings are a reproduction of the original chintz fabric used on the bed in 1816.

“A design for a bed,” shown on plate 9 of Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (London, 1793). (Courtesy, Yale Center for British Art, Friends of British Art.)

Detail of the right front post of the bed in fig. 29. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of a piece of the original English glazed cotton chintz used for bed hangings on the bed in fig. 29. (Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1934; photo, Walter Silver.)

Detail of the painted cornice with gilded medallion on the bedstead in fig. 29. (Photo, Dennis Helmar.)

A Roman carrying a fasces (wooden rods bound with straps around an ax head), an ancient symbol of united strength and power, from Cesare Vicellio and Ambroise Firmin-Didot’s Costumes anciens et modernes = Habiti antichi et moderni di tutto il mundo (Paris, 1860), pl. 4. (Courtesy, Indiana University; photo, HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Design for a “Bed Pillar” (detail) shown on plate 106 of George Hepplewhite’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (London, 1794). (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.) The upper reeded column is entwined with faux straps in imitation of a Roman fasces.

Field bedstead by Mark Pitman, 1817–1825. Mahogany, maple, pine, canvas, rope, brass, metal. H. 85", W. 59 1/4", D. 79". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1078; photo, Kathy Tarantola.)

Detail of the circular mahogany disc applied to the scroll on the headboard of the bedstead in fig. 37. (Photo, Kathy Tarantola.)

Detail of the pressed brass cap covering the metal bolt used to secure the front post to the side rail of the bedstead in fig. 37. (Photo, Kathy Tarantola.)

Detail of the turned urn finial on the tester of the bedstead in fig. 37. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the turned urn finial on the cornice of the desk and bookcase in fig. 2. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Sideboard by Mark Pitman, 1817–1818. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, metal. H. 42", W. 61 1/4", D. 22". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1063; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

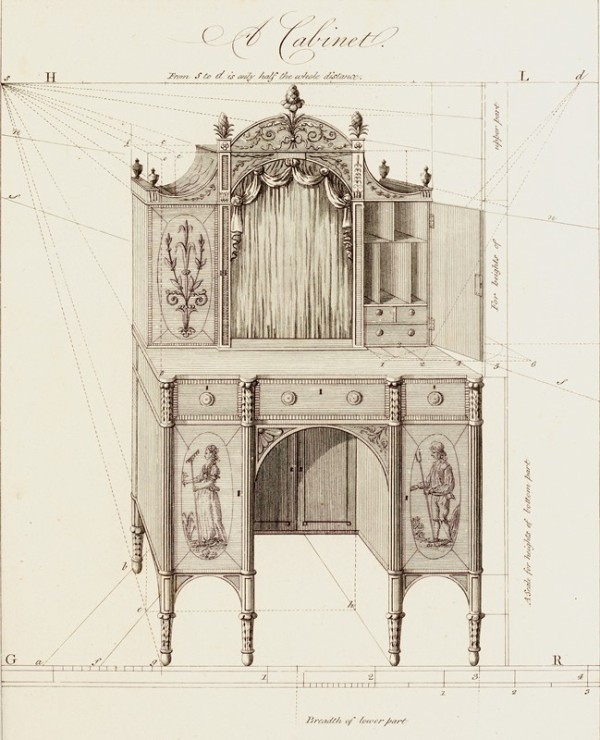

Design for “A Cabinet,” shown on plate 48 of Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (London, 1793). (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.) The lower section is similar in form to the sideboard in fig. 42.

Detail of an ovolo cap on the top of one of the engaged columns on the sideboard in fig. 42. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the carved floral motif on one of the engaged columns on the sideboard in fig. 42. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the acanthus-leaf carving on one of the engaged columns on the dressing chest in fig. 50. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of a design for “Ornament for a Tablet and Various Leaves,” shown on plate 11 of Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (London, 1793). (Courtesy, Getty Research Institute; photo, HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Secretary with tambour doors labeled by Mark Pitman, 1800–1810. Mahogany, birds-eye maple, Eastern white pine, oak, brass, bed ticking. H. 52 1/4", W. 38 1/4", D. 19". (Courtesy, Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, purchased through a bequest from Lulu C. and Robert L. Coller, Class of 1923, F.984.19.)

Detail of the label on the secretary in fig. 48.

Dressing chest with attached looking glass by Mark Pitman, 1817–1818. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, mirror glass, painted brass. H. 71", W. 44", D. 22 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1112.AB; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Dressing glass by William Hook (1777–1867), Salem, Massachusetts, 1818. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, white pine, mirror glass, metal, brass. H. 27", W. 27 1/2", D. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the estate of George Rea Curwen, 1900, 4134.83; photo, Kathy Tarantola.) This dressing glass was made for use on top of a bow front chest of drawers, also in the Peabody Essex Museum’s collection (4134.82).

Designs for brackets shown on plate 5 of the New-York Society of Cabinet Makers’ The New-York Book of Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet and Chair Work (New York, 1817). (Courtesy, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1939.) Several of the illustrated designs are in imitation of the ancient lyre and similar to the brackets on the dressing glasses in figs. 50 and 51.

Looking glass, Boston or Salem, possibly by Mark Pitman, 1800–1820. Mahogany, pine, mirror glass. H. 17 7/8", W. 31 3/8". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1116; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Dressing table by Mark Pitman, 1817–1818. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, brass. H. 38", W. 39", D. 17". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1111.AB; photo, Dennis Helmar.) The chalk inscription “Bottom” in Pitman’s handwriting is on the underside of the drawer unit.

Detail of a pressed brass foot imitating a lion paw on the drawer unit on the dressing table in fig. 54. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Chest of drawers by Mark Pitman, 1817–1818. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine. H. 41", W. 43", D. 21 3/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1082; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Washstand by Mark Pitman, 1817–1818. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine. H. 39 1/2", W. 19 1/2", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1081; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Washstand by Mark Pitman, 1817–1818. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, brass. H. 39 1/2", W. 19 1/2", D. 16 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1125; photo, Kathy Tarantola.)

Washstand by Mark Pitman, 1817–1825. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, brass. H. 39 3/4", W. 19 1/2", D. 16 3/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1105, washstand and R361.AB, ewer and basin; photo, Michael E. Myers.) Shown with an ewer and basin, English transfer-printed pottery, ca. 1817. The wash set is one of four purchased by the Ornes in 1818 and used with their washstands.

Looking glass with a shell ornament, Boston or Salem, Massachusetts, ca. 1817. Gilded wood, pine, mirror glass. H. 38 1/4", W. 22 3/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1083; photo, Michael E. Myers.) The Ornes purchased the mirror in 1817 to hang above one of their washstands.

Looking glass with floral ornaments, Boston or Salem, Massachusetts, ca. 1817. Gilded wood, pine, mirror glass. H. 39 1/2", W. 22 1/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1106; photo, Michael E. Myers.) The Ornes purchased the mirror in 1817 to hang above one of their washstands.

Night table by Mark Pitman,1817–1818; altered into a four-drawer display chest, ca. 1900. Mahogany, pine, brass. H. 29 1/2", W. 25", D. 18 3/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, FIC2019.7.1; photo, Kathy Tarantola.)

Design for a night table (detail), shown on plate 82 of the third edition of George Hepplewhite’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (London, 1794). (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.)

Commode or night table by Elijah Sanderson (1751–1825), Salem, Massachusetts, ca. 1800. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, white pine, brass. H. 29 1/2", W. 25 3/4", D. 19". (Private collection; photo, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.) Illustrated in Dean A. Fales Jr.’s Essex County Furniture: Documented Treasures from Local Collections, 1660–1860 (Salem, Mass.: Essex Institute, 1965), pl. 37.

Two-section dining table by Mark Pitman, 1817–1818. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, metal. Each section, H. 28 1/2", W. 54", L. 56" (fully open) (total table length 112"). (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1070; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Pembroke table by Mark Pitman, 1817–1818. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, brass, metal. H. 28 1/2", W. 42", D. 31". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1068; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Detail of the brass pull with thistle motif on the drawer of the table in fig. 66. (Photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Armchair, probably New York City, ca. 1817. Multiple woods, rush, and paint. H. 32 1/2", W. 20". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum; gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1069.2.) This armchair was from a set purchased by Sally and Joseph Orne about 1817 to be used with the dining table in fig. 65. Two armchairs and four side chairs survive in the collection from what was likely a larger set.

“Landscape” painted side chair, probably New York City, 1816. Multiple woods, rush and paint. H. 33 1/4", W. 18", D. 16". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of Arthur R. Sharp, Jr. and Mary Silsbee Sharp, 1972, M8541; photo, Kathy Tarantola.) This side chair was from a set used for dining on George Crowninshield’s yacht Cleopatra’s Barge.

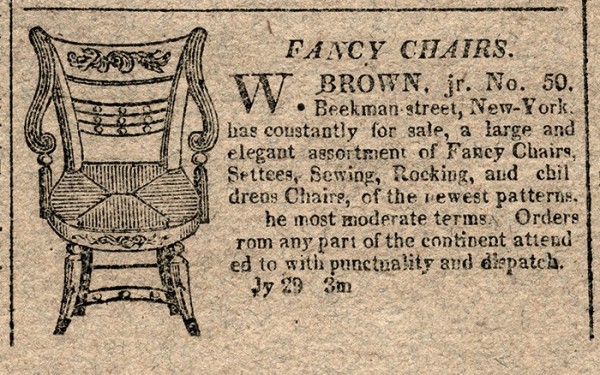

William Brown Jr.’s advertisement for “FANCY CHAIRS” in the Mercantile Advertiser (New York, N.Y.), February 15, 1816. (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.)

Pier glass with a cornucopia and grapes motif, Salem or Boston, Massachusetts, 1817. Gilded and ebonized wood, mirror glass. H. 45", W. 22", D. 2 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1066; photo, Michael E. Myers.) This looking glass was purchased by the Ornes in 1817 for their dining room to coordinate with the painted black and gold chair in fig. 68.

The Pitman dining furniture and other table accessories owned by Sally and Joseph Orne, installed in 2015 in the dining room that had been remodeled in 1835–1836 in the Ropes Mansion. (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum; photo, Kathy Tarantola.)

Grecian style sofa by Mark Pitman, 1817–1818. Mahogany, maple, pine, brass, with red wool upholstery from the 1890s. H. 38", W. 84 1/4", D. 24 1/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1048; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

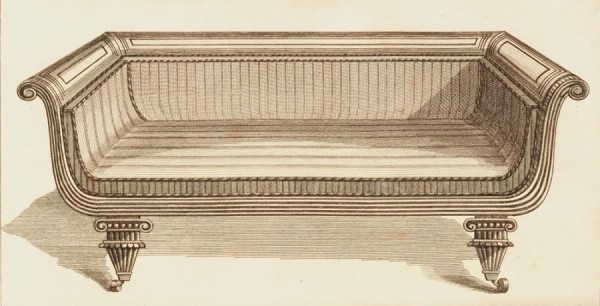

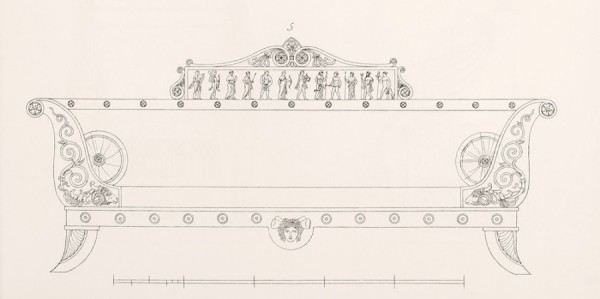

Design for a “Grecian Sofa,” shown on plate 73 of Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet Dictionary (London, 1803). (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.)

Detail of a front leg of the sofa in fig. 73. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

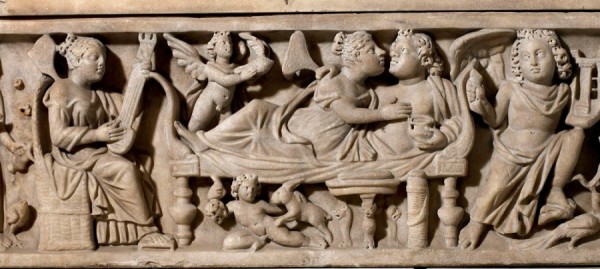

Detail of child’s sarcophagus depicting the marriage feast of Cupid and Psyche, Roman, 3rd century CE. Proconnesian marble. (Courtesy and © The Trustees of the British Museum.) The couple are seated on a sofa similar in form to the sofas in figs. 73 and 77.

Grecian style sofa by Mark Pitman, carving attributed to Samuel Field McIntire (1780–1819), ca. 1815. Mahogany, maple, with modern upholstery. H. 37 1/2", W. 85", D. 24 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of Mrs. Robert Johnston, 1984, 136133; photo, Dennis Helmar.) The sofa was made for the family of Jonathan Peele Saunders (1785–1844).

Design for a settee (detail), shown on plate 18 of Thomas Hope’s Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (London, 1807). (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.)

Detail of the brass floral mount on the crest rail of the sofa in fig. 73. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the brass floral mount on the arm of the sofa in fig. 73. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the brass floral mount on the front seat rail of the sofa in fig. 73. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Side chair (from a set of ten) by Mark Pitman, 1817–1818. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, cane. H. 33", W. 17", D. 18". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memoral, 1989, R1131.1.)

Side chair, attributed to Isaac Vose and Son, Boston, Massachusetts, with Thomas Wightman, carver, 1824–1825. Mahogany, birch, modern upholstery. H. 33", W. 19", D. 17". (Private collection; photo, David Bohl.) This chair is from a set originally owned by Samuel Atkins Eliot and Mary Lyman Eliot.

Easy chair by Mark Pitman, 1817–1818. Mahogany, various hardwoods, later upholstery. H. 40 1/2", W. 28 1/2", D. 30". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1114; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Detail of the front leg and rocker on the easy chair in fig. 84. (Photo, Dennis Helmar.)

James Frothingham (1786–1864), Elizabeth Ropes Orne, ca. 1822. Oil on canvas. H. 42", W. 35" (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R746.)

Bow front chest of drawers by Mark Pitman, 1810–1825. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, brass. H. 39 1/2", W. 44 1/4", D. 20 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1113; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Detail of the brass drawer pull with sea shell motif on the chest of drawers in fig. 87. (Photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Dressing box with attached looking glass by Mark Pitman, 1817–1825. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, ivory, metal, mirror glass. H. 16 1/2", W. 14 7/8", D. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1103; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Toy cradle by Mark Pitman, 1820–1830. Mahogany. H. 8 1/2", W. 14", D. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1098; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Toy washstand by Mark Pitman, 1820–1830. Mahogany, brass. H. 8 1/4", W. 4 1/2", D. 4 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1099, washstand and R351.2, plate; photo, Dennis Helmar.) Shown with miniature plate, English, ca. 1825.

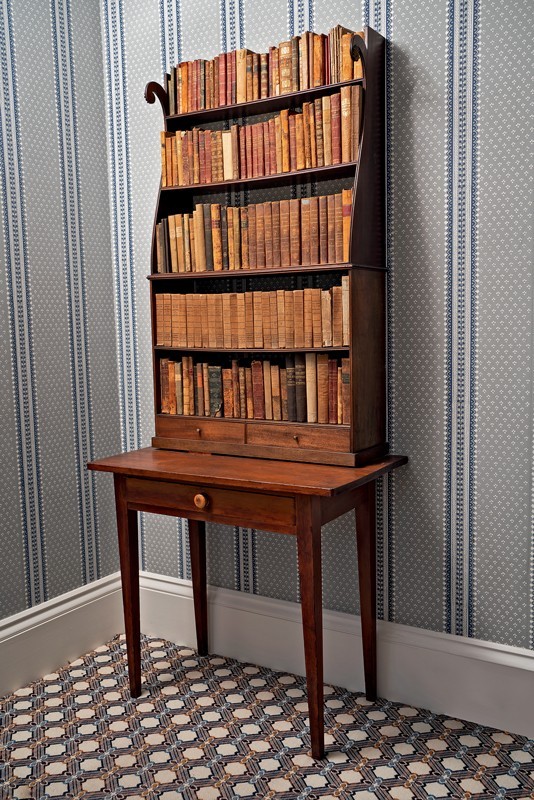

Two-part bookshelf with two drawers by Mark Pitman, 1828. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, brass. H. 45 1/2", W. 28", D. 8 1/2". Shown on top of a single drawer table by Mark Pitman, 1807–1825. Pine, maple. H. 29", W. 32 1/4", D. 17 3/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1101, R1100; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Detail of the gilded medallion on the right scroll of the bookshelf in fig. 92. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

The Elizabeth Ropes Orne bed chamber in the Ropes Mansion, containing the bedstead in fig. 37, washstand in fig. 57, and mirror in fig. 60. (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989; photo, Allison White.) The room was restored in 2015 using reproductions of period wallpaper, ingrain carpeting, and cotton dimity bed hangings.

Grecian style Pembroke table by Mark Pitman, 1826. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, unidentified wood, brass, metal. H. 29", W. 46 1/2", D. 24 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1054; photo, Kathy Tarantola.)

Detail of the mahogany veneered panel with fillet moldings set into the end of the apron rail on the table in fig. 95. (Photo, Kathy Tarantola.)

Grecian style work table by Mark Pitman, 1828. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, glass, brass, metal, paper, silk fabric. H. 28", W. 19 1/4", D. 19 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1136; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

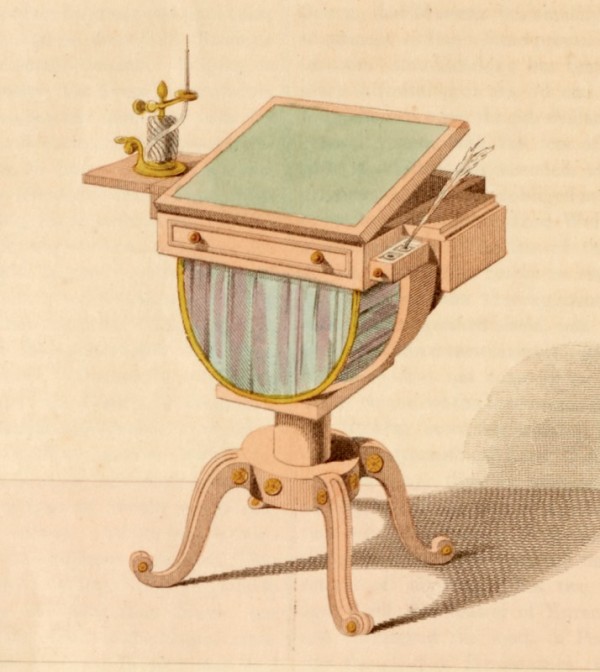

Design for a “Ladies Work Table” (detail), shown on plate 35 of Ackermann’s Repository, no. 30 (June 1811). (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.)

Detail of the original cut-glass drawer pulls on the work table in fig. 97. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the original plaid silk fabric, with a fragment of gold fringe, covering the storage drawer on the work table in fig. 97. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the swing bracket used to support the raised leaf on the work table in fig. 97. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Cylinder desk and stand by Mark Pitman, 1827 or 1828. Desk: mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, baize fabric, brass, glass bottles with silvered caps, fabric glued to the reeds. H. 7", W. 15 1/2", D. 11 1/2". Stand: mahogany, mahogany veneer, unidentified wood, brass. H. 28 1/2", W. 21 1/4", D. 17 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989. R1109, R1110; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

John Harden (1772–1847), Harden Family at Brathay Hall, 1827. Watercolor on paper. Dimensions not recorded. (Courtesy, Abbot Hall, Lakeland Arts Trust, Cumbria, England.) The young woman by the window is using a lap desk on a stand similar to the one in fig. 102.

Cylinder desk by Mark Pitman shown in fig. 102. (Photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Stand with hinged octagonal top by Mark Pitman shown in fig. 102. (Photo, Dennis Helmar.)

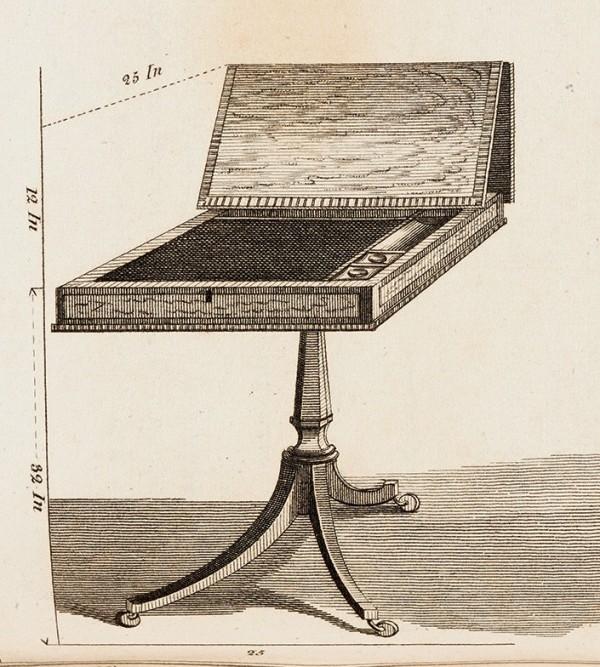

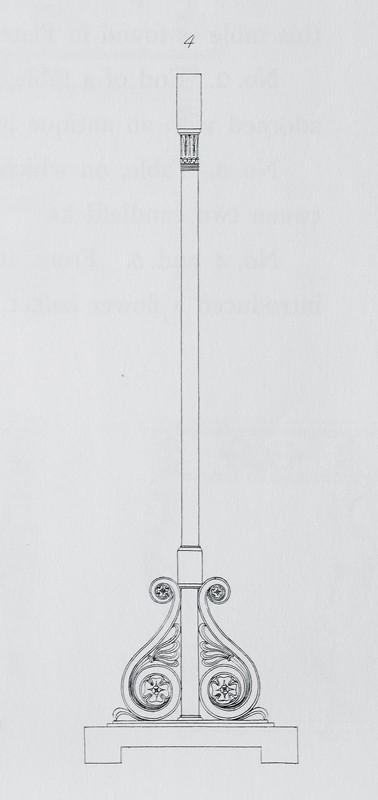

Design for “A Lady’s Writing Table” (detail), shown on plate 71 of Thomas Sheraton’s The Cabinet Dictionary (London, 1803). (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.)

Detail of the carved scrolls on the upper legs on the stand in fig. 102. (Photo, Dennis Helmar.)

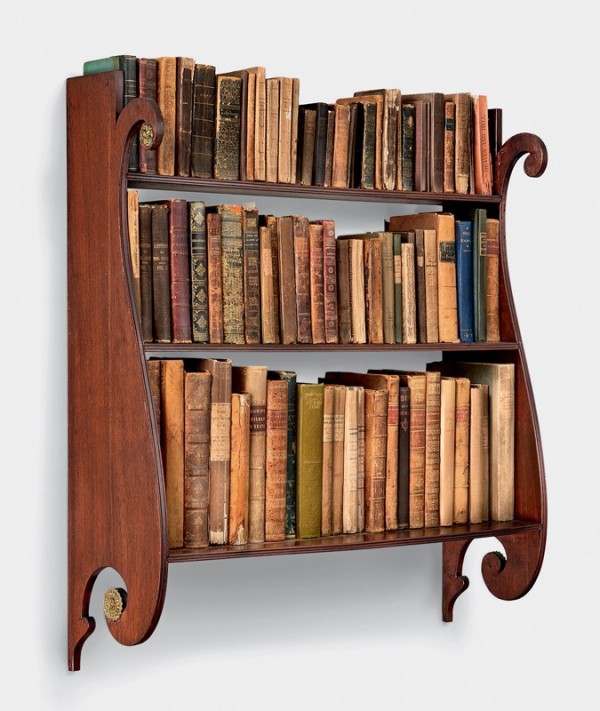

Bookshelf by Mark Pitman,1824–1828. Mahogany, brass mounts. H. 31", W. 27 7/8", D. 8 1/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1115; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Design for a “Profile of a dressing glass” (detail), shown on plate 14 of Thomas Hope’s Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (London, 1807). (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.) The scrolled brackets are similar in shape to the sides of the bookshelf in fig. 108, with a similar floral motif on the end of the upper scroll.

Detail of the brass rosette on the upper scroll of the bookshelf in fig. 108. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the brass medallion on the lower scroll of the bookshelf in fig. 108. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

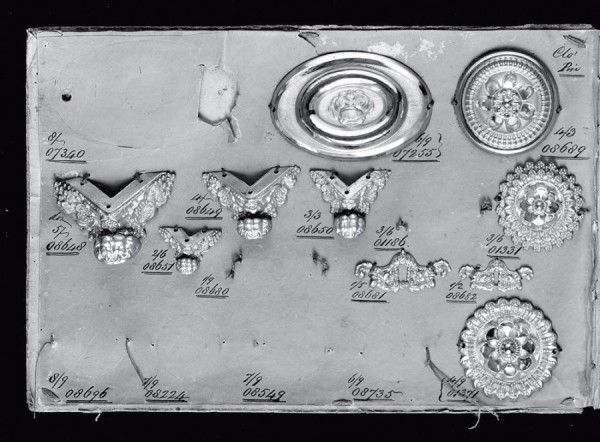

Brass hardware sewn into the trade catalogue issued by Thomas Potts, Designs for Curtain Pins, Curtain Poles, Drawer Handles, Knob Cupboard Turns, Bed Caps, Clock Pins, Doorknobs, etc. (Birmingham, England, 1829–1833). (Courtesy, Rhode Island School of Design Museum.) The medallion marked “01331” is similar to the medallion in fig. 111 used on the bookshelf in fig. 108.

Gray marble chimneypiece made by John Templeton, Boston, Massachusetts, 1835. H. 49 3/4", W. 68 3/4", D. (shelf) 8 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989; photo, Michael E. Myers.) The chimneypiece was purchased by Sally (Ropes) Orne and her sister, Abigail Ropes, for the front parlor of the Ropes Mansion during the 1835–1836 renovation; it was moved to a second-floor bedroom in 1894.

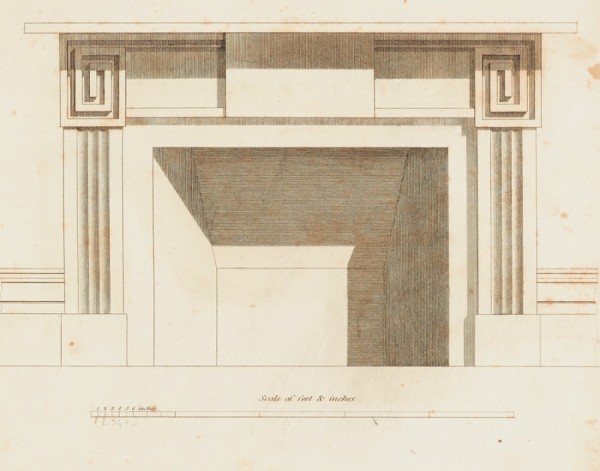

Design for a “Chimney Piece” in the Grecian style, shown on plate 50 of Asher Benjamin’s The Practical House Carpenter (Boston, 1830). (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.)

South wall of the front parlor of the Ropes Mansion, showing the commode, pier glass, and tabourets installed as part of the 1835–1836 renovation of the room. (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

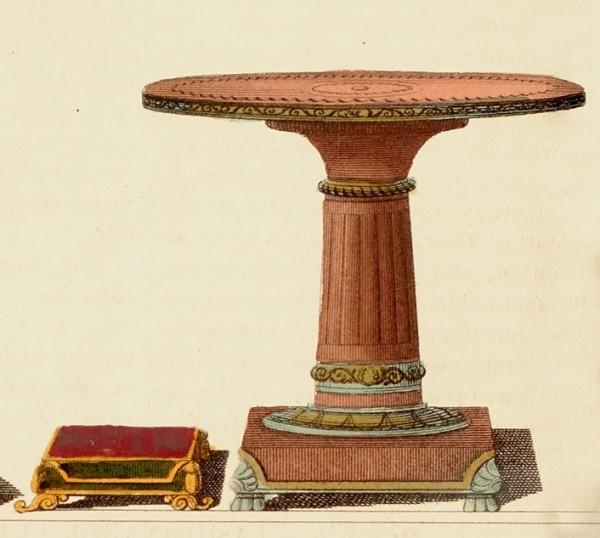

Design for a “Commode, Pier Glass & Tabourets,” shown on plate 26 of Ackermann’s Repository, second series vol. 6, no. 35 (November 1, 1818): opp. p. 307. (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art Library; photo, Internet Archive, the American Libraries collection.)

Commode or pier cabinet by Mark Pitman, 1835–1836. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, marble. H. 33 3/4", W. 40 1/4", D. 19 7/8". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1038; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Design for a commode (detail), shown on plate 39 of Thomas King’s The Modern Style of Cabinet Work Exemplified, in New Designs, Practically Arranged (London, 1839). (Photo, HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Tabouret (one of a pair), attributed to Kimball and Sargent, Salem, Massachusetts, 1835–1836. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, modern needlework. H. 18", W. 20 3/4", D. 13". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1037.1, .2; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Detail of a 1915 photograph showing the original needlepoint covering attributed to Sally (Ropes) Orne on the tabouret (or its mate) in fig. 119. (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum [Ropes Papers, box 21, folder 3].)

Footstool by Mark Pitman, with needlework covering attributed to Sally (Ropes) Orne, 1830s. Mahogany, pine, wool. H. 4 5/8", W. 13 3/8", D. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1079; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Pole screen by Mark Pitman, with needlework attributed to Sally (Ropes) Orne, 1835–1836. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, wool, silk backing fabric, glass, metal. H. 63 7/8", W. 16 7/8"; screen H. 16 1/2", W. 15 7/8". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1055; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Detail of the needlework panel on the pole screen in fig. 122. (Photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Footstool (one of a pair) attributed to Mark Pitman, 1830s. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, modern needlework. H. 6 1/4", W. 13 1/2", D. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1044.1; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Detail of a 1915 photograph showing the original floral needlework attributed to Sally (Ropes) Orne on the footstool (or its mate) in fig. 124. (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum [Ropes Papers, box 21, folder 3].)

Design for a pole screen (detail), shown on plate 5 of Thomas King’s The Modern Style of Cabinet Work Exemplified, in New Designs, Practically Arranged (London, 1839). (Photo, HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Detail of the leaf carving on the base of the pole screen in fig. 122. (Photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Detail of the finial with leaf carving on the pole screen in fig. 122. (Photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Detail of the leaf carving on the mid-section of the pole screen in fig. 122. (Photo, Dennis Helmar.)

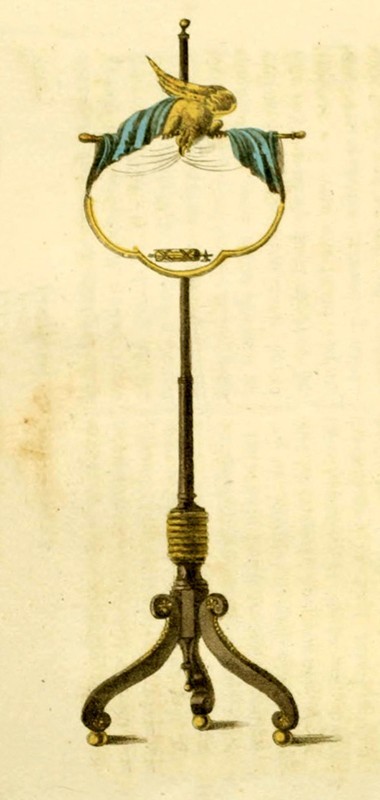

Tabletop fire screen, attributed to Mark Pitman, needlework attributed to Sally (Ropes) Orne or Abigail Ropes, 1830s. Mahogany, pine, wool, silk fabric, metal, glass. H. 27 1/2", W. 8"; screen H. 9 7/8", W. 10 7/8", D. 3/4". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1042; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Design for a fire screen (detail), shown on plate 32 of Ackermann’s Repository 14, no. 84 (December 1815): opp. p. 348. (Courtesy, Library of the Philadelphia Museum of Art; scan, Internet Archive.)

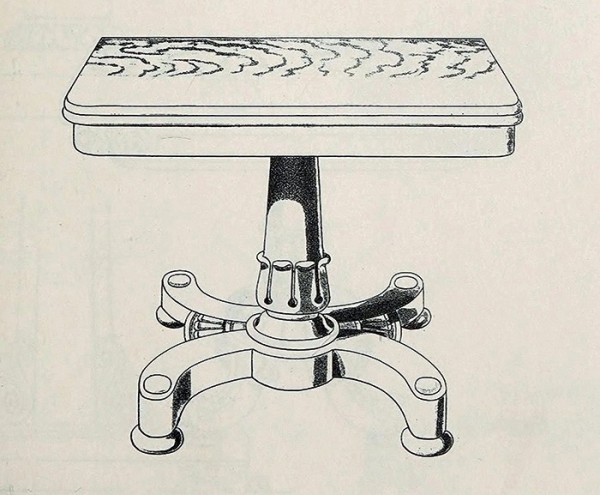

Grecian style card table by Mark Pitman, 1830s. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, metal. H. 28 1/2", W. 36", D. 17 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1085; photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Card table (one of a pair), attributed to Thomas Seymour (1771–1848), Boston, Massachusetts, 1816. Mahogany, various woods. H. 30 7/8", W. 36 1/4", D. 18". (Courtesy, National Park Service, Adams National Historical Park.) The tables were made for Peter Chardon Brooks.

Design for a card table (detail), shown on plate 43 of Thomas King’s The Modern Style of Cabinet Work Exemplified, in New Designs, Practically Arranged (London, 1839). (Photo, HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Detail of one of the feet with domed cap and bead edge on the table in fig. 132. (Photo, Michael E. Myers.)

Detail of the turned base on the right front column of the chest of drawers in fig. 137. (Photo, Kathy Tarantola.)

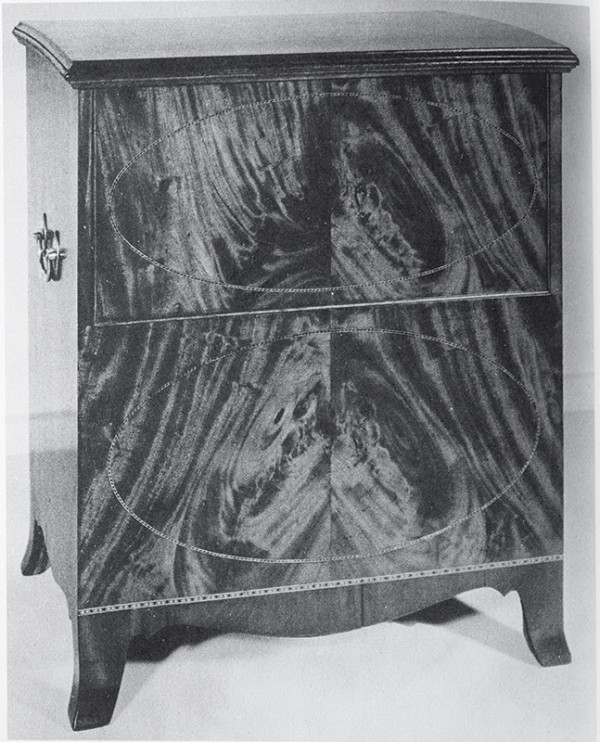

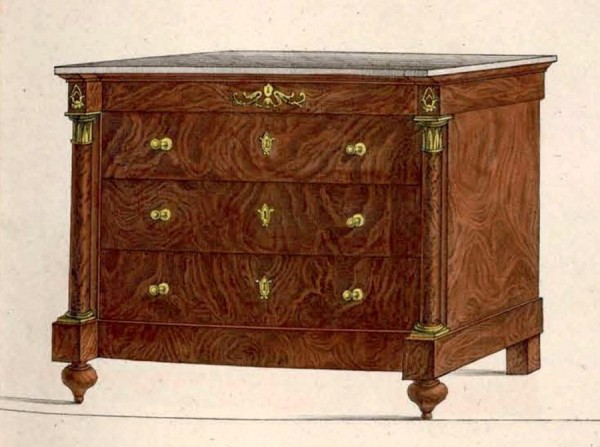

Chest of drawers by Mark Pitman, 1833. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, metal. H. 42", W. 47", D. 22". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of Mary Osgood Hodges, 1918, 107547; photo, Kathy Tarantola.)

Design for a “Commode en acajou flambé” (chest of drawers with flaming mahogany) (detail), shown on plate 328 of Pierre de La Mésangère’s Collection de meubles et objets de goût (Paris, ca. 1802–1818). (Courtesy, Bibliothèque de l’Institut national d’histoire de l’art, collections Jacques Doucet.)

Round-top table attributed to Mark Pitman, 1830s. Mahogany, mahogany veneer, pine, metal. H. 29 1/4", Diam. top 28 1/2". (Courtesy, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of the Trustees of the Ropes Memorial, 1989, R1128; photo, Dennis Helmar.)

Designs for a “Stool and Reading Table” (detail), shown on plate 30 of Ackermann’s Repository 8, no. 47 (November 1812): opp. p. 289. (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum.)

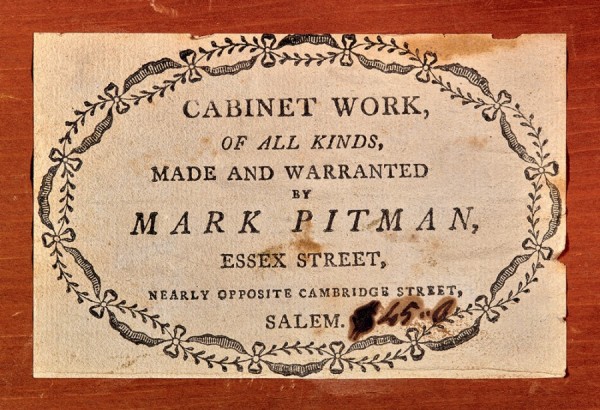

AN EXTRAORDINARY GROUP OF forty-nine examples of furniture made between 1812 and 1840 by Salem cabinetmaker Mark Pitman (1779–1855) for various members of the Ropes-Orne family survives in the Ropes Mansion, one of the historic houses owned by the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts (fig. 1; Appendix A). Nine labeled forms dating from 1806 to 1814 securely establish Pitman’s early design preferences and meticulous woodworking skills (figs. 2, 3).[1] While none of the forms in the Ropes Mansion bears his label or signature, many are documented by surviving receipts, which along with other written material reveal the intimate relationship Pitman enjoyed with three generations of the family (see Appendices C and D). Between 1807 and 1853, he rented his cabinetmaking shop at 324 Essex Street from them. Its location next to the Ropes Mansion and directly across the street from his own home at 327 Essex Street assured his availability to make furniture on demand.[2] This close proximity also enabled him on a daily basis to perform other services for the family, including milk delivery, caring for the family cat, witnessing their wills, and making their coffins.

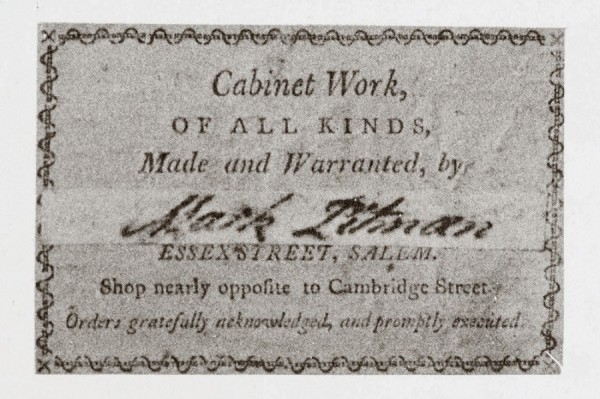

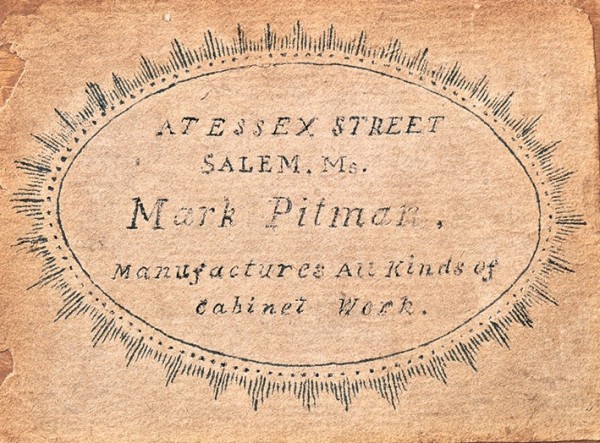

Baptized at the Tabernacle Church in Salem on June 20, 1779, Pitman was the son of mariner Joseph Pitman (d. 1794) and his wife, Bethiah (d. 1811). His marriage to Sophia Francis (d. ca. 1864) on March 10, 1799, produced a large family, including at least one son, Mark Jr. (1814–1904), who also trained to be a cabinetmaker.[3] Pitman’s training remains a matter of speculation. If he followed a traditional path and apprenticed to a cabinetmaker when he turned fourteen in 1793, his formal training would have ended in the late 1790s, perhaps followed by a few years of working as a journeyman. A slant-top desk in a private collection, bearing his bold signature and the date 1798, is his earliest known piece. Pitman’s first paper label has his hand-written signature pasted over the printed name of cabinetmaker Josiah Caldwell (dates unknown) (fig. 4).[4] While little is known of Caldwell’s career, historians have speculated that Pitman may have trained or worked with him before taking over his shop “nearly opposite Cambridge Street” and used his labels, which proclaim, “Orders gratefully acknowledged, and promptly executed.” Caldwell moved his shop farther up Essex Street next to Rev. Dr. Barnard’s house and advertised on March 16, 1810, that he “carries on the cabinetmaking business in all its branches” and has “CHAIRS of every description constantly on sale.”[5]

Pitman’s name appears among the Ropes Family Papers for the first time on a receipt dated July 16, 1807, one month after Elizabeth (Cleveland) Ropes (1757–1831) moved her family into the Ropes Mansion following an extensive renovation (fig. 5; Appendix C, no. 1). She was the second wife and widow of merchant Nathaniel Ropes III (1759–1806), who had died the previous August while the family was living at their farm in Danvers, Massachusetts. He left a good estate despite suffering from the ravages of alcoholism, which caused his premature death at the age of forty-seven.[6] He had three children from his first marriage, to Sarah Putnam (1765–1801): Nathaniel IV (1793–1885), who was away at boarding school, and daughters twelve-year-old Sarah (1795–1876), known as Sally, and eleven-year-old Abigail (1796–1839), who moved into the Ropes Mansion with their stepmother. The executors gave a $250 “allowance to widow for necessary furniture,” and Elizabeth immediately started to use some of it to buy a “pine wash stand” and a “frame for a writing desk” from Pitman (Appendix C, no. 1).[7] Pitman’s name also appears on a list of people indebted to the estate of Nathaniel Ropes III, a $100 promissory note on which Pitman was paying interest.[8]

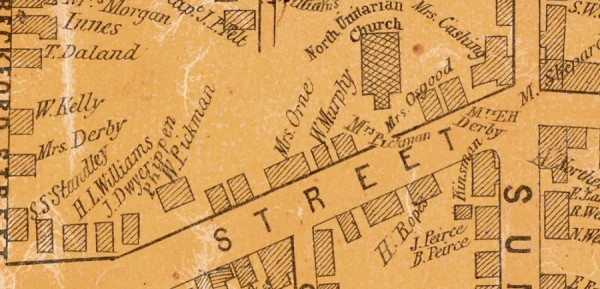

Nathaniel Ropes III had acquired full ownership of the 1727 Ropes Mansion during the final settlement of the estate of his father, Judge Nathaniel Ropes II (1726–1774), in 1799.[9] He also inherited the empty lot on the western side of the house, where he quickly built four commercial shops around 1800. In 1809 those shops were occupied by “Benjamin Blanchard, hairdresser; Mark Pitman, cabinet maker; Nathaniel Lang, saddler; and Stephen Driver, boot and shoemaker.”[10] Pitman’s rent payment for the year 1809 is the only one to survive, being a ledger entry: “Oct.1 cash rec’d M. Pitman for rent 26.25.”[11] By 1849 the Ropes Mansion was owned by Nathaniel III’s daughter, Sally (Ropes) Orne, and in a letter from that year she expresses her frustration with being the owner of the shops because the tenants refuse to listen to her, declaring, “a woman should not have tenants.”[12] An 1851 map of Salem shows two separate structures on the shop lot (fig. 6). As indicated by Salem directories, Pitman occupied one of the shops until 1853; by 1874 both shop buildings had been demolished. The earliest known photograph of the Ropes Mansion, taken in the 1890s, shows a matched board fence running along the now empty western lot where the shops once stood (fig. 1).

Mark Pitman is mentioned thirty-two times in receipts, account book entries, and letters that survive in the Ropes Family Papers. Spanning the years between 1807 to 1839, these records detail the multitude of tasks performed by Pitman for the family, from delivering foodstuffs and doing odd jobs around the house to making furniture. Since the Ropes household was comprised entirely of women during this period, Pitman played an important role in handling small emergencies, many relating to fixing or replacing the woodcock on the kitchen water pump, which connected to a private aqueduct system.[13] He fixed other broken things, including door hinges, the doorbell, windows, and blown-off shutters. Other domestic tasks ranged from putting up curtains, measuring land, and framing and varnishing a map. He used his woodworking skills to make utilitarian items, including a pot handle, bobbins, bed rods, small boxes, and a tray. Pitman also served as cat-sitter. While visiting her brother Nathaniel Ropes IV in Cincinnati in 1839, Sally (Ropes) Orne wrote to her cousin back in Salem, “I hope she [Mrs. Pickman, their next-door neighbor] does not think I left her [the cat] to starve, I sent both to Mr. Pitman + Marks to feed them in our absence + I hope she would not be neglected.”[14]

In addition to all of this quotidian personal interaction, the family ordered numerous pieces of fine furniture from Pitman. Surviving receipts document Pitman making twenty-nine forms, of which nine survive (Appendix C). In addition, there are forty other pieces of furniture in the house made by Pitman without a corresponding receipt. Between 1807 and 1816 Elizabeth (Cleveland) Ropes purchased a washstand, a frame for a writing desk, a table, a traveling desk, a work table, a work box, and a bedstead, of which only the table, bed, and traveling desk survive. The “mahogany traveling desk” purchased on June 16, 1812, and costing eight dollars, is a plain rectangular box with a simple inlaid light wood shield around the keyhole (fig. 7; Appendix C, no. 4). The top portion of the box folds back on hinges to abut the lower section, forming a large slanted writing surface, and the thin-hinged board in each of the sections provides access to a lower storage compartment. The green baize covering the boards, originally a single piece of fabric, is now split in the middle. The open storage area along the top edge has a removable curved tray for writing implements (with storage space below) and three wells, one with a slanted floor (perhaps for red wax sticks for sealing envelopes) and the other two for glass bottles (one with ink and the other with sand to absorb wet ink). Elizabeth was a prolific letter writer, and the brass side handles allowed her to carry the closed desk from one place to another to take advantage of the best light, heat, or cool breezes depending on the season.

Elizabeth may also have been responsible for asking Pitman to make the family’s medicine chest (fig. 8). Pitman used dovetail construction to join the sides of the plain pine box together and small brads to nail the bottom board to the sides. The front and side edges of the hinged lid are rounded. The exterior of the box is painted a mottled green, the underside of the lid a light gray, with the interior left unpainted. Thin partitions divide the space into twelve compartments of varying size to accommodate glass bottles. The arrangement follows that of several other medicine chests dating from the early nineteenth century, which retain original bottles with paper labels identifying the contents (fig. 9). The two largest spaces held bottles of bark powder: Peruvian bark to treat fever, and willow bark, a form of aspirin for treating pain. Smaller bottles contained liquids and oils, such as castor oil (a laxative), laudanum (an opium-based painkiller), and smelling salts (to revive the unconscious).[15] A pharmacist filled the labelled bottles as needed. Most commercially produced medicine chests came with a manual detailing how to combine various ingredients to treat a specific aliment. Homeowners also collected remedies from friends, family members, and their doctor; several such remedies survive among the Ropes Family Papers. Considered a standard item for the home, this box saw a great deal of use in a family that endured one medical crisis after another.

Elizabeth was well educated and took great interest in teaching her three stepchildren, especially Sally and Abigail. The girls attended Miss Hetty Higginson’s school in their early years to learn arithmetic, reading, sewing, and to cultivate artistic interests. A painted box and work table relate to this educational effort (figs. 10–12). Elizabeth Ropes paid Pitman three dollars in 1816 for “a work box,” but the price suggests it was much larger than the small box with painted decoration in the Ropes collection (Appendix C, no. 6). The construction details, notably the finely crafted partitions on the interior of the box, relate to those crafted by Pitman in the work table drawer. Two small pieces of wire inserted through the sides and into the edge of the lid serve as the hinges. Two holes on the front of the box indicate there was originally a simple handle, perhaps of string for pulling the box off a shelf. Like many sewing boxes of this period, the interior is lined with glossy paper, in this case colored a vibrant pink. The painted decoration on top, consisting of various borders surrounding a rose branch with a pink bud and leaves, is less accomplished than the painting on the work table (figs. 12–16, 21). Made of bird’s-eye maple, the work table has Pitman’s refined construction details, including the partitions dividing the upper drawer into eight compartments for sewing and writing implements. The slender turned legs have an ovolo cap set into the top surface, a feature characteristic of Pitman’s work (Appendix B, no. 6). On the right side of the case, the lower section of the rail is missing, having been part of a frame that slides out from the case with an attached cloth bag for storage.

The form of the table relates closely to other two-drawer work tables produced in Essex County between 1810 and 1825, many with similar romantic landscapes painted on the sides by young women, often while attending a female academy.[16] Sally would have been fifteen in 1810, the average age of most of the other documented table artists. She may also have done the painting well after leaving school, suggested by her purchases of a paint box from Cushing and Appleton in Salem on March 7, 1822, and another one the following year.[17] The oak leaf border around the top edge was a popular motif on tables in the 1820s (fig. 13). Glass drawer knobs also came into vogue in the 1820s, and their selection is consistent with Sally’s embrace of the latest design trends. Yet despite all of this circumstantial evidence, a more plausible attribution can be made for Sally’s daughter, Elizabeth Ropes Orne (1818–1842), who seems likely to have done the paint decoration in the 1830s. A large number of drawings and watercolors in the Ropes Family Papers attributed to her are evidence of her skill, and several of them have details similar to those painted on the table. For example, the pointed arch bridge in the scene on the table’s left side is very similar to the bridge in one of her pencil sketches (figs. 16, 17).[18]

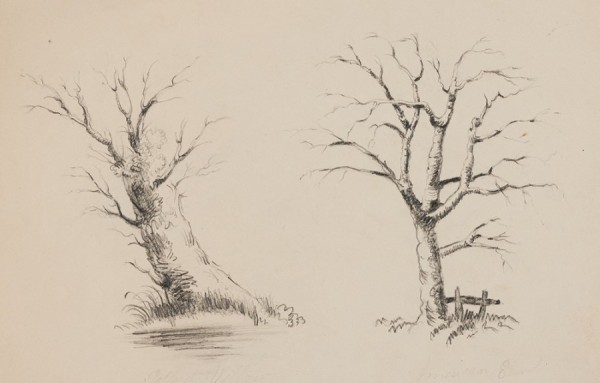

These scenes of classical ruins and idyllic landscapes possess a greater degree of sophistication than the imagery found on most other schoolgirl tables, suggesting Elizabeth may have worked with her cousin and close friend, the artist James Arthur Cleveland (1811–1868). In August of 1836, Cleveland advertised in the Salem Gazette that he was willing to give lessons in drawing providing twelve pupils signed up for the course, noting “Drawing from nature will be particularly attended to as soon as the scholars may have attained a sufficient knowledge of the rudiments.”[19] Several drawings in the Ropes collection appear to be Cleveland’s work, suggesting a student-teacher relationship with Elizabeth (fig. 18). In 1839 Cleveland and his wife traveled with Elizabeth and her mother to Cincinnati to visit her uncle, Nathaniel Ropes IV. Nathaniel gave her an expensive blank book upon their arrival, and Cleveland became the first person to make an entry, sketching a small landscape with details similar to those found on the table (fig. 19). That same year, Cleveland published his Elements of Landscape Drawing in Cincinnati, with twelve lithographed plates focused primarily on how to draw trees, many similar in detail and technique to those found on the table (figs. 20, 21).[20]

The marriage of Sally Ropes to her first cousin, Joseph Orne, on May 22, 1817, led to Pitman’s largest commission from the family (figs. 22, 23). He made at least twenty-two pieces of the furniture for the couple’s first home, a grand three-story town house designed by Salem’s most renowned architect, Samuel McIntire (1757–1811) (fig. 24). Built in 1795 for Joseph’s father (and Sally’s uncle), Captain William Orne (1752–1815), the house was prominently situated on Court Street (later renamed Washington Street), near McIntire’s imposing 1785 courthouse. Joseph acquired the house during the settlement of his father’s estate, and while he did not take legal possession until April 1, 1818, once the couple announced their engagement in 1816 they immediately started to make plans to furnish the house in a fashionable manner using the considerable fortune Joseph had also inherited from his father.[21]

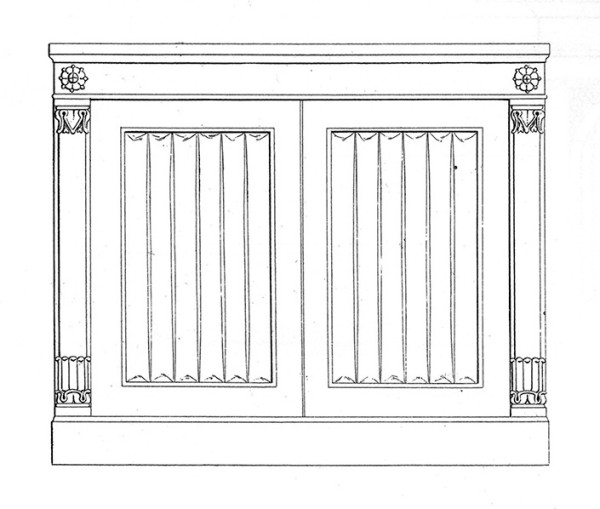

At the time of their engagement, Joseph was studying theology at Harvard College in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and had already used Pitman’s services. In February of 1816, Pitman put rockers on a chair, made a bed canopy with urns, a thermometer case, and a “set of bookcases” for Joseph’s ever-growing library (Appendix C, no. 7). Only the two-part bookcase and possibly the bed canopy survive (fig. 25). A very similar bookcase was made later (fig. 26). Both bookcases consist of two separate units, with the upper case set back behind an applied molding that runs along the front and sides, crown moldings of the same design, and two doors with six panes of glass in each of the sections. They are both made of inexpensive pine grain-painted to simulate mahogany or rosewood, with an interior painted the same ocher color. Differences include the methods used for constructing the bases and installing the glass. The 1816 bookcase has a projecting base with an applied molding and straight bracket feet, and the panes of glass are set into a rabbet on the inner edges of the molded rails and stiles of the door using traditional glazing bars (fig. 27 [above]).[22] The later bookcase has a curved apron flush with the bottom rail of the lower doors; the panes of glass are held in place by a molding with an astragal bead glued along the front edges of the stiles and rails of the doors, with matching glazing bars (fig. 27 [below]). The front edges of the shelves in the later bookcase have a double bead; the shelves in the earlier bookcase are square cut and plain. Both cabinets remain filled with many of the books acquired by Joseph and Sally, offering insight into their broad interests in European and American history, literature, natural history, and religion.

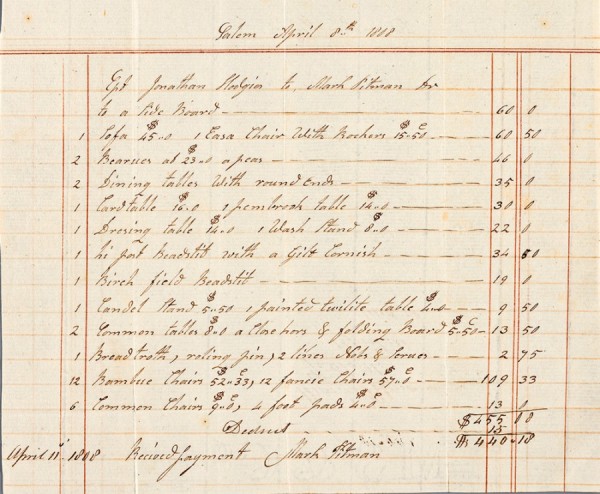

While payment for the four-poster bed with gilded cornice in figure 29 is documented (see Appendix A, no. 6), surprisingly, no receipts survive for the Ornes’ wedding furniture still in the house, including a dressing table, bureau, dressing chest with attached mirror, sideboard, Pembroke table, two-part dining table, easy chair with rockers, night table, sofa, set of mahogany chairs, and three nearly identical washstands. Many of these same forms appear on a Pitman receipt listing the furniture made for the wedding of two of Sally’s relatives in 1808 (fig. 28). This receipt and several Figure 28 Receipt for Capt. Jonathan Hodges from Mark Pitman, April 8, 1808, for furniture supplied for the marriage of his daughter, Elizabeth H. Hodges, to George Cleveland of Salem. (Courtesy, Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum [Hodges Family Papers, box 22, folder 17].)

other orders for wedding furniture from this period provide a contextual understanding of the Ornes’ commission and suggest there was a communal agreement in the Salem region in the early decades of the nineteenth century as to what was necessary and fashionable for establishing a comfortable upper-middle-class home.[23] Sally’s first cousin, Elizabeth H. Hodges (1789–1834), married George Cleveland (1781–1840) on April 27, 1808. In the months before their wedding, the couple worked to furnish their first home in Boston. Pitman’s receipt, submitted to the bride’s father, lists the furniture he produced for the couple as well as sets of “bamboo” (Windsor chairs with simulated bamboo turnings) and “fanci” (paint-decorated) chairs that Pitman likely acquired from independent chair makers who specialized in specific forms. Pitman clearly played a large role in helping to coordinate all of the furnishings for the Boston couple and likely did the same for Joseph and Sally.

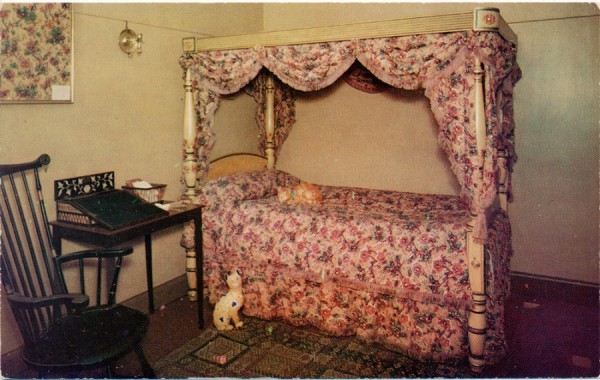

One of the more important Hodges pieces was “a high post bedstead with a gilt cornice” costing thirty-four dollars and fifty cents. The Orne bed matches that description and appears to have been a gift from Elizabeth (Cleveland) Ropes (fig. 29). She made two payments to Pitman in May of 1817 just before the Ornes’ wedding, recording an eighteen dollar payment “for a bedstead purchased last October” and an additional $9.67 to settle Pitman’s account.[24] The $27.67 total is close to what the Hodges paid. The design of the Orne bed relates closely to the bedstead made for George Crowninshield Jr. for use on Cleopatra’s Barge, America’s first ocean going luxury yacht (fig. 30). Launched in October of 1816, the boat, with its unique design and elaborate furnishings, created a public sensation. Thousands of people toured the boat before it left on its maiden voyage to Europe the following spring. Sally’s cousin, Samuel Curwen Ward (1767–1817), served as clerk on the voyage and, as a close friend of the owner, he likely provided the family with special access to view the boat.[25]

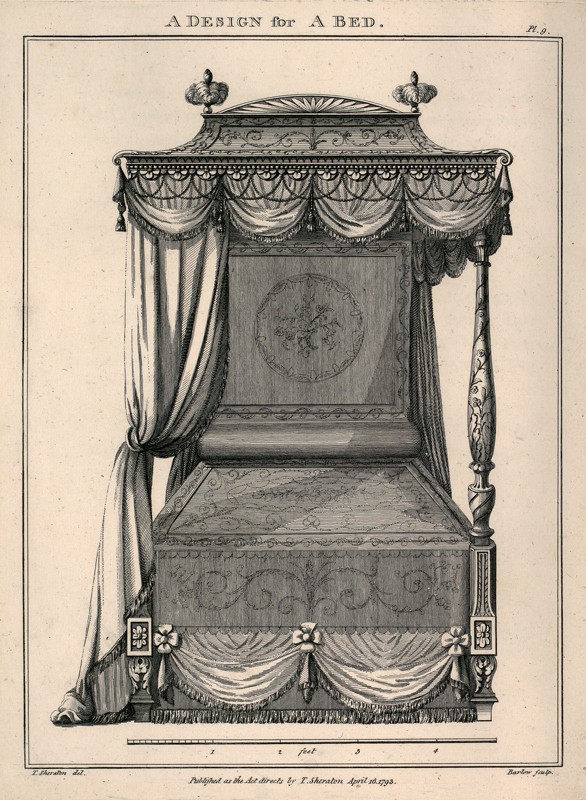

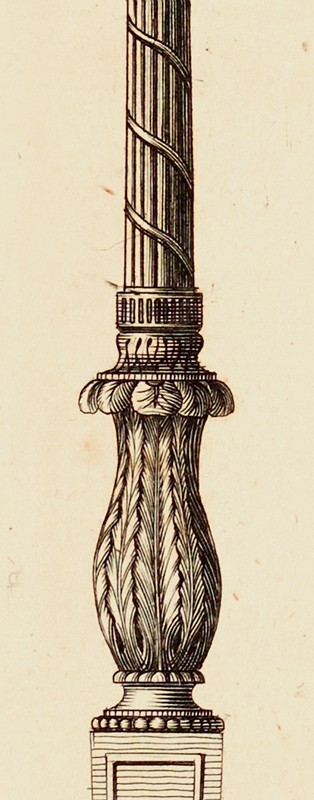

The front posts on both beds show the influence of British designer Thomas Sheraton. In his influential The Cabinetmaker and Upholsterer’s Drawing-Book (London, 1790–1793), Sheraton published a number of designs for bed pillars, noting if they should be executed in mahogany with carving or painted. The front pillar in his “Design for a Bed” has the same basic component elements as the posts on the two Salem beds, consisting of a round tapering upper shaft above an elongated urn, followed by the square rectangular section containing the brass caps covering the holes for the bolts joining the posts to the rails (figs. 31–33). The round turned foot tapers in the opposite direction from the upper shaft. The Ornes chose mahogany pillars to match the other furniture selected for their bedroom, relying on the complex and elegant turned details for the decorative effect (fig. 32). Crowninshield chose to have his posts painted, resulting in fewer turned details. On a yellow ground, green and gold banding highlight various transition points, and a grape vine and scrolling acanthus leaf ornament adorn the central parts of the post.[26]

The cornices on both beds are similar in design and retain their original paint and decorative accents. Narrow reeded boards on the front and sides are attached to a curved rectangular panel at the front corners, accented with a large brass medallion. The reeds on the Orne cornice are consistent in size and are crossed every twelve inches with a flat angled band, imitating the leather straps on a fasces, a bundle of wooden rods surrounding an axe head that served as an ancient Roman symbol of united strength and authority (figs. 34, 35). The same detail appears on a bed pillar in George Hepplewhite’s The Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (London, 1788), a pattern book widely used in Salem (fig. 36). Both the Crowninshield and Orne bedsteads were originally dressed with a lively English cotton chintz. The Ornes chose a bold pattern with alternating columns of oak leaves and pansies printed in yellow, blue, and burnt orange on a honeycomb background (fig. 33).

The field bed in the Ropes collection was also likely part of the Orne wedding order, perhaps intended for the guest chamber or in anticipation of having children (fig. 37). Other documented wedding orders include a field bed, such as the “birch field bedstead” costing nineteen dollars made for the Hodges in 1808 and the “birch canopy bedstead” costing twenty-two dollars made for Lucy Hill (1783–1869) in 1810.[27] While the use of less expensive birch was common, wood analysis has revealed that the posts and backboard of the Orne field bed are made from the same mahogany used to make the larger marriage bed. The four matching posts on the Ornes’ field bed are similar to the front posts on their wedding bed, and the headboard has a similar shape with a different cap on each end of the scroll. Consisting of a simple domed circle with a plain dome in the center, the cap is similar to the brass caps on the bolt holes (figs. 38, 39). The “bed canopy with urns” Pitman made for Joseph Orne in 1816 may have been repurposed for this bed (Appendix C, no. 7). The turned details and acorn finial on the urns are more robust than the more delicate details on Pitman’s earlier urns (figs. 40, 41).

Like the bedsteads, all of the other pieces of the Ornes’ wedding furniture express Salem’s interpretation of the British Regency or late neo-classical style, inspired by various British pattern books and, more directly, by the very stylish furniture produced by Boston cabinetmakers, most notably John (1738–1818) and Thomas Seymour (1771–1848), who produced furniture for many of the leading families in Salem.[28] The sideboard Pitman made for the Ornes incorporates key characteristics of the style in Salem (fig. 42). The most prominent is the use of turned legs with bold reeding on the upper portion engaged with the case. Similar legs appear in Thomas Sheraton’s design for the lower portion of a dressing cabinet published in 1793 and in Boston work soon after 1800 (fig. 43). Like the Orne sideboard, the four front legs in Sheraton’s design divide the flat facade of the long rectangular cabinet into three bays. The two outer bays have a single drawer with a cabinet below. Pitman chose to fill the space below the central drawer with two small drawers and two bottle drawers flanking a central cabinet. The serpentine shape of this section relieves the otherwise flat facade and required additional work to create the individual curved shapes of each drawer front. While the top board in Sheraton’s design (like most Boston examples) shows smooth semi-circular projections above the engaged columns, Pitman, like most Salem cabinetmakers, preferred using a turned ovolo cap (fig. 44). Each is set partially into the top surface, with its rounded edge meeting the half-round molding applied to the edge of the top board. Salem makers also preferred legs with well-rounded ball feet and large turned wooden drawer pulls to blend visually with the rich graining of the mahogany veneer.

Carved capitals above the reeding on the legs became a hallmark of Salem case pieces, in part because of the number of skilled carvers offering their services to multiple cabinetmakers. Thomas Sheraton’s design shows carved acanthus leaves above the reeding, but Pitman chose a distinct abstracted floral motif with a star-punched background characteristic of Salem carving (fig. 45). The Ornes’ dressing chest features acanthus leaves on the capitals similar in detail to a number of the leaves in Sheraton’s drawing book, which he included for carvers to copy (figs. 46, 47). Pitman did not start using the services of master carver Joseph True (1785–1873) until May of 1819, suggesting this carving is not True’s work.[29] Pitman may have used the services of another carver, or possibly he executed this carving himself.

A review of the turned legs on all of the other pieces of Orne wedding furniture demonstrates that Pitman did all of his own turning. There is a consistent vocabulary of favorite details, always executed with precision and skill. Many turned elements on the legs line up perfectly with details on other parts of the case or frame. An early example of Pitman’s interest in turning and his shift to the British Regency style is found on a labeled desk (fig. 48). Half columns with turned details flank the lower tambour doors, providing a transition to the square tapering legs associated with his earlier style. While there are no carved details on any of the other legs adorning the Orne wedding furniture, the use of the same bold convex reeding with well-rounded tops and ball feet gives this entire suite of furniture a cohesive look of restrained classical elegance.

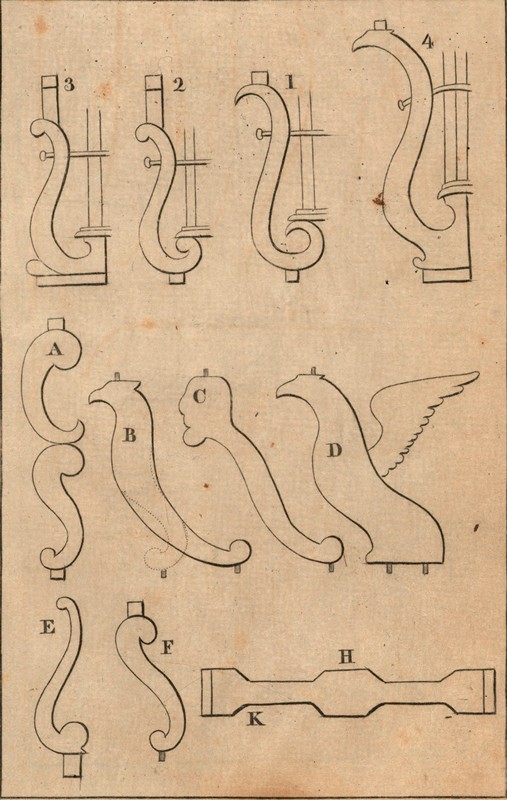

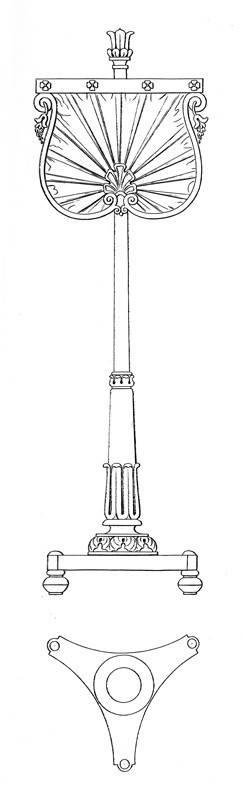

Thomas Seymour popularized the dressing chest with an attached mirror in Boston and made several of his finest examples for Salem residents.[30] Pitman’s dressing chest mimics Boston examples, having a three-drawer unit built into the top surface, to which is attached a rectangular looking glass (fig. 50). Pitman’s mirror is set into a simple half-round veneered frame with a gilded liner and topped with a shaped crest. The frame is attached to straight reeded standards with scrolled side supports. A metal rod inserted through the bracket, standard, and frame allows the mirror to swivel. The molded brass knob on the end of the rod and the metal ball finials on the posts have traces of the original brown paint to simulate wood. The shape of Pitman’s side brackets lacks the complex curves and gracefulness of many Boston examples, but identical brackets on a dressing box made in 1818 by William Hook (1777–1867) suggest it was favored in Salem (figs. 50, 51).[31] Based on an ancient lyre, the shape was one of the more popular motifs used to express the classical style; it appears numerous times in the 1817 edition of The New-York Book of Prices for Manufacturing of Cabinet and Chair Work (fig. 52). Like the Hook brackets, Pitman’s brackets were originally accented at the ends of the scrolls with brass medallions, now missing.

The simple shaped crest on the mirror of the Orne dressing chest relates to the frame of a wall mirror in the Ropes collection (figs. 50, 53). The shape of the crest, side brackets, and base on the wall mirror evolved in the eighteenth century and remained popular into the 1820s, evidenced by labeled mirrors by several different makers.[32] The ease of cutting the shapes from thin mahogany boards facilitated the replication of the design. Pitman may have intended this looking glass, with a distinct gilded liner in the frame, to be hung over a dressing table with a two-drawer unit on top that Pitman also made for the Ornes (fig. 54), thus imitating in appearance and function the dressing chest in figure 50. Alternatively, the Ornes may have purchased it from another maker, and it provided the inspiration for Pitman’s design of the mirror on the dressing chest.

While most Boston dressing chests have a straight facade, Salem makers preferred a swelled or bow front seen in the Orne dressing chest and dressing table (figs. 50, 54). The Hodges paid fourteen dollars for their dressing table. The capitals on the legs of the Orne table are plain (having a slight ogee cyma recta shape), with a bead at the base that meets the applied bead on the lower edge of the front and side rails. A distinguishing feature is the use of four brass paw feet to elevate the two-drawer unit about a half inch above the top surface (fig. 55). A single brass nail driven through a hole in the center of each foot attaches the unit. While the restrained look of Pitman’s larger case pieces stems in part from the use of plain turned wooden drawer pulls, he also occasionally used pressed brass pulls—in this instance to complement the brass feet.

The dressing chest and a smaller straight front four-drawer bureau in the suite have recessed panels on the sides of the cases set into stiles and rails with beaded edges, another Regency design feature (figs. 50, 56). The beading is also the dominant decorative detail on the smaller chest’s turned legs, which lack vertical reeding and carving. Three sets of double beads align with the cockbeads around the edges of the drawers. Pitman’s fondness for beading is evident throughout his work. He consistently added an applied cockbead to the lower edges of all of his case pieces, table rails, and around the edges of most drawers. Well-rounded single beads, astragal beads, and reeds (three or more beads) are also common details on his turned legs and bed pillars. On his later Grecian pieces, beads appear on the edges of the shelves in the sideboard, bookshelves, and table legs (figs. 42, 92, 95, 97, 108).

Some of Pitman’s more complicated turning appears on the delicate legs of three nearly identical mahogany washstands in the house (figs. 57–59). While the Hodges’ wedding receipt lists only one washstand costing four dollars, the Ornes appear to have ordered more, suggested by their purchase of “4 sets of ewers and basons” in 1818 for their new house.[33] Two of these sets survive, both featuring British blue transfer-printed glazed pottery with romantic ruins in a landscape setting (one set is shown in fig. 59). Two of the washstands have identical turnings and are likely part of the wedding order (figs. 57, 58). Different drawer pulls suggest they were intended for different rooms. The one with a turned wooden pull, like those on the dressing chest and bureau, may have been intended for the master bedchamber, while the one with a pressed brass pull may have served a guest chamber. The third washstand has slightly different turnings and may be part of the wedding suite, or it could have been made later for their daughter Elizabeth (fig. 59).

In each stand, Pitman provided a large circular hole in the center of the top surface to accommodate the washbowl. The hole is large enough to secure the base, yet small enough to elevate the bowl well above the varnished surface. A shaped valance along the front edge blocks the view of the base below the surface. The cyma or ogee outline of the valance is a variant of the valances on the pigeonholes in Pitman’s desks, such as the example in figure 2, and echoes the double reverse curve of the sides of the high gallery, designed to contain splashes of water. The two small semi-circular shelves in the corners of the gallery held accessories, as did the two additional holes cut into the top surface next to the washbowl—perhaps a soap dish and a drinking glass. The lower shelf provided a place to put the water pitcher after filling the basin. The single drawer below held washcloths, toothpaste, and other supplies. To complete this hygienic ensemble, the Ornes purchased several tabernacle form looking glasses to hang above the stands, including two with gilded frames that have three dimensional ornaments, one with a seashell, the other with flowers (figs. 60, 61).[34]

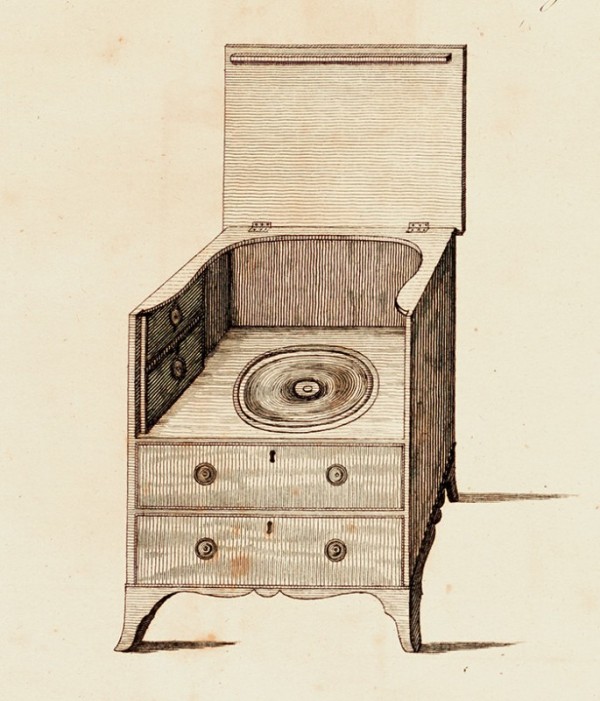

The Hodges receipt lists “1 painted twilight table $4,” most likely a reference to a “Night Table,” a small cabinet designed to conceal a chamber pot for use in the bedroom during the night. An altered night table by Pitman in the Ropes collection may have been part of the Orne furniture (fig. 62). Its size matches the dimensions for a night table in the Salem Cabinetmakers Price Book, “the common kind, 2 feet 4 inches, 2 feet deep without the pan [$]12.”[35] The Orne table retains the original top, back, feet, and sides with brass handles for lifting the piece, but the facade and some interior elements were altered about 1900 to turn it into a small chest of drawers. Hepplewhite’s pattern book shows multiple night table designs, including one with an open lid (fig. 63). A night table by Salem cabinetmaker Elijah Sanderson (1751–1825) has a veneered facade with two inlaid ovals, visible when the lid is closed during the day to conceal the purpose of the table (fig. 64).

It is clear from their other purchases that Sally and Joseph intended to make dining an important part of their life together. In addition to the sideboard in figure 42, Pitman made a large two-section dining table (fig. 65). The Hodges table is described on their receipt as “2 dining tables with rounded ends 35.00,” a reference to the then popular sectional tables featuring an end unit with a semi-circular top. Each section of the Orne table consists of a rectangular top, with a hinged drop leaf on either side. The smaller leaf on the end of the table has rounded corners, while the larger inner leaf is rectangular. When the smaller leaf is raised, two shaped brackets swing out from the rail to provide support. The larger leaf is supported by a single leg that swings out on the end of a fly rail; the other three legs supporting the top are fixed. These two independent sections can be configured in multiple ways to create tables of different sizes, depending on the number of guests. When both sections of the table are joined together with all four leaves raised, the table measures 112 inches long. When both leaves are folded down, an unused section could easily be stored against a wall or, more common during the period, under the staircase in the front hall.

A matching Pembroke table was also made for the dining room, and it has equally sized falling leaves with rounded corners and four fixed legs of the same design as those on the dining table (fig. 66). Pitman charged the Hodges fourteen dollars for their Pembroke table. On the Orne table, a single shaped bracket swings out from the rail to support a raised leaf. The long drawer built into one end of the frame has a pressed brass pull embossed with a thistle plant, reflecting Sally’s love of Scotland and her favorite author, Sir Walter Scott (fig. 67).

Like the Hodges, who purchased twelve fancy painted chairs, the Ornes selected a set with rush seats to use with the dining and Pembroke tables (fig. 68). Two armchairs and four side chairs survive from what was likely a larger set. The chairs are closely related in form to the painted chairs used for dining on Cleopatra’s Barge (fig. 69). Both sets likely originated in New York City, where fancy chair makers like William Brown Jr. (1785–1819) advertised similar forms and assured customers that “Orders from any part of the continent attended to with punctuality and dispatch” (fig. 70).[36] The Orne chairs have a black ground with streaks of red, which stands in sharp contrast to the gold paint used to accent various details on the arms, legs, and back. The wide crest rail features clusters of grapes with leaves. Grapes also appear flowing out of a cornucopia on the upper panel of a large pier glass purchased by the Ornes in 1817 for their dining room (fig. 71). The half-spindle frame with alternating sections of black and burnished gold is well-matched with the coloration of the chairs.

The Ornes also purchased hundreds of other dining-related wares during various shopping sprees in Salem and Boston in November and December of 1817. They bought damask tablecloths and napkins, a three hundred-plus piece Chinese export porcelain dinner service, a two hundred-piece set of Anglo-Irish cut glass, bone- and steel-handled knives and forks, and sterling silver serving spoons. Almost all of these purchases survive in the Ropes collection, providing an extraordinary opportunity to appreciate the functionality of Pitman’s dining room furniture and the role it played in creating a harmonious expression of the fashionable neo-classical style (fig. 72).

The Hodges furniture receipt lists two upholstered pieces of seating furniture, a sofa costing forty-five dollars and an easy chair with rockers costing fifteen dollars and fifty cents; both forms survive among the Orne furniture. The sofa is based on Thomas Sheraton’s design for a “Grecian Sofa” published in 1803 (figs. 73, 74). Innovative features include a back equal in height to the sides, scrolled arms, and reeded turned legs, which Sheraton called “stump” feet (fig. 75). Inspiration came from sofas with similar features depicted on various ancient archaeological artifacts, such as a Roman sarcophogus dating from the third century (fig. 76). The Ornes would have viewed their sofa as a very stylish modern expression of classical taste, reflective of their interest in ancient Greece. They owned a copy of the two-volume set of Archaeoligia Graeca, or, The Antiquities of Greece by John Potter, published in 1818, with engravings of classical buildings and artifacts. A very similar sofa has been published as being the work of Jonathan Peele Saunders (1785–1844) of Salem and made for his own wedding in 1811 (fig. 77).[37] Since there is no evidence that Saunders, who was a civil engineer, was also a cabinetmaker, both sofas can be assigned to Pitman based on the similarity of various details to other pieces of Orne furniture. These include the reeding along the front rail and arms (like the bed cornice), the treatment of the reeding and other turned details on the legs, and the use of stamped brass mounts as decorative accents.

The use of metal mounts on furniture is one of the defining decorative features of the British Regency and French neo-classical styles during the early nineteenth century. Urban American cabinetmakers used imported mounts widely, and pattern books show their effective use on most furniture forms. Thomas Hope’s design for a sofa made for his own home shows rosettes as terminal points on the ends of the arms and scrolls on the elaborate central panel on the crest rail (fig. 78). Hope noted: “These ornaments in bronze, which, being cast, may, where ever a frequent repetition of the same forms is required, be wrought at a much cheaper rate then ornaments in other materials, only producible through more tedious process of carving.”[38]

The elongated oval panel above the crest rail on the Orne sofa has small gilt brass floral medallions on the end of the curve, set within an ebonized bead (fig. 79). More elaborate medallions appear on the scrolls of the arms, and larger examples are applied above the legs on the seat rail, set within a square frame reminiscent of the panel above the legs on the ancient sofa (figs. 80, 81, 76). The maroon velvet upholstery currently on the sofa dates from the late nineteenth century. While the original covering has not been determined, the black paint around all of the medallions suggests black horsehair may have been the original covering given its wide use on seating furniture during much of the nineteenth century.

The raised panel on the crest rail of the sofa is similar in shape to the rounded end crest rails on a set of ten mahogany side chairs likely made by Pitman as part of the wedding suite or possibly added later, in the 1820s (fig. 82). The design of the chairs reflects the ancient klismos form, with saber legs on both the front and rear of the chair. Chairs of this form were being produced by Boston’s leading makers, including Isaac Vose (1767–1849), in the early 1820s, usually with a degree of carving on the crest rail and the single stay rail below (fig. 83). The only attempt at ornamentation on the Orne set is the inclusion of figured mahogany veneer on the raised panel on both the crest rail and single stay rail in the center of the back. The Orne chairs may have been fitted with cushions. In his popular serial publication Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufacture, Fashion, and Politics (commonly known as Ackermann’s Repository), Rudolph Ackermann illustrated many different chair designs with caned seats for the parlor and dining room, with options for cushions. In one instance he noted: “the cushion, separate, secured with straps underneath.”[39]

The Ornes’ easy chair with rockers has turned front legs characteristic of Pitman’s work, and his hand is also evident in the carefully chamfered glue blocks in the corner of the seat frame (figs. 84, 85). The rear legs are square with a slight taper; both front and rear legs are pinned to the well-shaped rockers. Easy chairs had been popular in New England since the early eighteenth century, traditionally made to comfort an elderly or infirm person in their bedchamber.[40] The form’s presence among the furnishings ordered by two young couples in their early twenties suggests another usage. Since most surviving easy chairs do not have rockers, Pitman’s use of them seems innovative and may be one of the reasons for their popularity with young couples anticipating children. Rocking provides comfort to a mother during pregnancy, while nursing, or when trying to get a child to fall asleep. Such a chair would also have been an ideal place to sit for long hours reading, especially during the winter when the high back and side wings added extra warmth. Joseph paid Pitman to add rockers to another chair in 1816, suggesting a clear family preference for the form. Since upholstery was an independent craft from cabinetmaking, Pitman would have turned the wooden frame over to an upholsterer for covering. Upholsterer Asa Lamson (1783–1858), who lived in the neighborhood, may well have done the original work. In 1828 he charged Elizabeth (Cleveland) Ropes six dollars and fifty cents for “a chair with stuft back.”[41] Since slipcovers were the preferred covering for an easy chair due to their changeability, a fully upholstered chair often had plain linen as the final covering.

Amid all of this furnishing activity, Joseph’s health continued to decline from the effects of consumption. He finally succumbed to the disease on September 3, 1818, at the age of twenty-two, six months after the birth of their only child, Elizabeth Ropes Orne (fig. 86). For a variety of reasons, both financial and emotional, Sally decided to sell the Orne house back to Joseph’s family. On June 14, 1819, Joseph’s sister and recent widow, Mrs. Eliza (Orne) Wetmore (1784–1821), purchased the house on the eve of her marriage to Daniel Appleton White (1776–1861).[42] Sally and her infant daughter returned to live in the Ropes Mansion with her stepmother Elizabeth and sister Abigail. She brought all of her wedding furnishings with her, causing a major upheaval in the house to accommodate them.

During the next decade, Sally continued to order furniture from Pitman to meet the family’s changing needs, and in 1825 she paid sixteen dollars for a “French birch bedstead” (Appendix C, no. 9). The term “French” on the receipt may refer to the size of the bed, being larger than a single bed but not quite a full double bed, rather than a reference to the then popular French bed with matching low head and footboard, placed against a wall with drapery suspended from the ceiling.[43] Furthermore, many artisans used the term “French” during this period to mean something in the French taste. It is not clear for whom this bed was intended. Elizabeth turned seven in 1825, and it may have been part of a refurnishing plan for her room; alternatively, it may have been acquired for another family member or servant. If this bed was used by Elizabeth during her formative years, it was later replaced by the field bed in figure 37 that she is known to have used in her room as an adult and in which she died in 1842.

In addition to the washstand in figure 59 discussed earlier, a four-drawer bureau and small dressing box are, by tradition, also associated with Elizabeth’s room (figs. 87, 89). The bow front bureau has two construction details that differ from the two wedding chests in figures 50 and 56. There are no inset panels on the sides of the case, and several plain horizontal boards cover the entire back, compared with the more complex paneled construction found on the other two chests (see Appendix B, no. 10). This suggests this could be an earlier chest or one made with simplified construction techniques because it was intended for a child’s room. The reeding on the upper legs continues almost to the top of the column without a pronounced capital. Instead of wooden drawer pulls, Pitman used pressed brass pulls embossed with spiral seashells, one of Elizabeth’s primary collecting interests, made evident by the many shells that remain on display in her bedroom (fig. 88). The single-drawer dressing box, traditionally used on top of a chest of drawers, has straight reeded posts and ebonized ball feet, features also found on small dressing boxes produced in Boston.[44] The metal ball finials are smaller versions of the balls on the posts on the larger dressing chest (fig. 50). A metal pin secures the frame of the mirror to the standards, allowing it to swivel. The turned knob on the end of each pin is made of ivory, the same material used to make the turned drawer pulls.

Pitman also made two pieces of miniature furniture for Elizabeth to play with, scaled to her favorite dolls. The toy cradle is a small version of full-size cradles popular in Salem, with a flat top hood with sloping sides and a cyma-shaped valance similar to those on Pitman’s washstands (fig. 90). The toy washstand is a simplified version of an adult washstand, with a plain gallery and single drawer with a brass knob (fig. 91). Each piece displays Pitman’s meticulous joinery and the care he took to shape even the smallest detail.