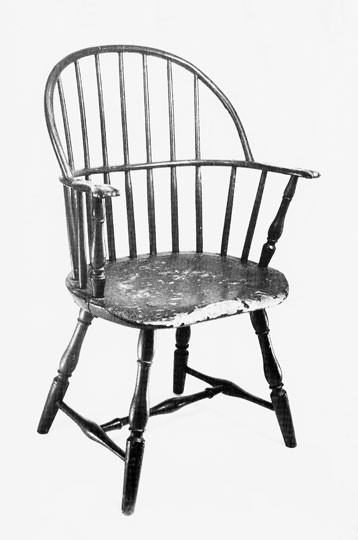

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1760. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, maple, and tulip poplar. H. 38 3/8", W. 21 5/16" (seat), D. 15 3/8" (seat); seat height: 17 7/8"; seat depth/seat width: .721; rail width: .995"; rail thickness: .744"; arm support angle: 6°. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The hoop is replaced.

Detail of the arm rail repair on the chair illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the underside of the armchair illustrated in fig. 1, showing vestiges of the original green paint on the legs and stretchers. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

William Cox, armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1770. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, maple, and white pine. H. 36 3/4", W. 21 5/8" (seat), D. 16 1/8" (seat); seat height: 16 3/4"; seat depth/seat width: .751; rounded rail width: 1.042"; rail thickness: .709"; arm support angle: 15°. (Private collection; photo, Martin Schnall.) The underside of the seat is marked “COX” and branded “EGB.” The right arm is an early replacement made of maple in the same style as the original.

Detail showing structural failure of the arm rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the underside of the armchair illustrated in fig. 4, showing seat cracks at the arm supports and between the rear legs. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left arm (from the sitter’s perspective) of the armchair illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The laminated sections of the knuckles are thicker than those on most Windsor chairs, and they do not flare outward as is usually the case.

Armchair, Massachusetts, ca. 1770. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, unidentified softwood, and maple. H. 37 5/8", W. 20 7/8" (seat), D. 14 11/16" (seat); seat height: 16 1/8"; seat depth/seat width: .707; flat-back rail width: 1.003", rail thickness: .612"; arm support angles 7° (right) and 10° (left). (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The hoop has an early repair, and handmade tension rods have been added to strengthen the arm supports. The rear legs and medial stretcher are replaced.

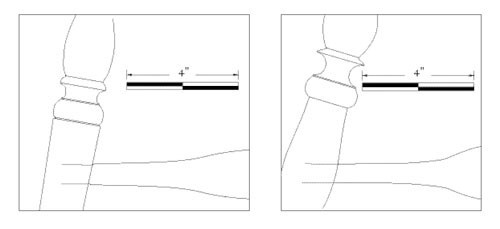

Detail comparing the flat-back arm rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 8 (left) with the rounded rail of the armchair illustrated in fig. 4 (right). (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

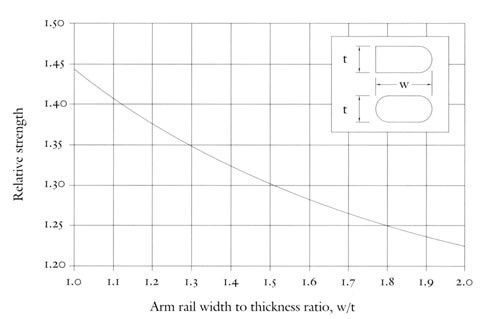

Graph showing the relative strength of flat-back and rounded arm rails. Results are generalized using the dimensionless parameter w/t where w is rail width and t is rail vertical thickness. The flat-back arm rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 8 is 1.004" wide and .612" thick; its w/t ratio is 1.639 and its relative strength ratio is 1.275, making it about 27.5% stronger than a rounded rail of the same size.

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, maple, and tulip poplar. H. 37", W. 21 3/16" (seat), D. 16 1/4" (seat); seat height: 17 1/2", seat depth/seat width: .770; flat-back rail width: 1.087"; rail thickness: .733"; arm support angle: 11°. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The maker of this chair and the example illustrated in fig. 12 used seventeen pins and seventeen nails to secure the hoop, each joint of the arm supports, the knuckles of the arms, the legs at the seat, and every other spindle. He did not use fasteners on the stretchers.

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, maple, and tulip poplar. H. 35 7/8", W. 21 7/16" (seat), D. 16 1/4" (seat); seat height: 17 5/8"; seat depth/seat width: .764; flat-back rail width: .985", rail thickness: .737"; arm support angle: 10°. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The medial stretcher is replaced and the legs are extended. The chair retains much of its original green paint.

Detail showing the right arms (from the sitter’s perspective) of the chairs illustrated in figs. 11 and 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Two pins secure the side laminates and two more secure the lower laminates. The gouge cuts used to define the scroll volutes are slightly different..

Detail of the underside of the armchair illustrated in fig. 11, showing the scribe marks likely used to denote the leg and pin positions. (Photo, Martin Schnall.)

Side view of the armchair illustrated in fig. 11, showing the bent seat and seat pins. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail showing the upper surfaces of the right arms (from the sitter’s perspective) of the chairs illustrated in figs. 11 and 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Similarities in arms indicate that the maker used patterns.

Overall side views of the armchairs illustrated in figs. 11 and 12. (Photos, Gavin Ashworth.) The back and arm rail of the chair on the right (fig. 12) have a more pronounced slope.

Overall side views of the armchairs illustrated in figs. 4 and 12. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The chair on the left (fig. 12) has greater leg splay than the sack-back on the right.

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Tulip poplar, maple, oak, and hickory. H. 37", W. 21 1/4" (seat), D. 16 3/4" (seat); seat height: 17 1/2"; seat depth/seat width: .741. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.)

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Oak, hickory, maple, and tulip poplar. H. 37", W. 21 1/4" (seat), D. 15 1/4" (seat); seat height: 17 1/2"; seat depth/seat width: .741. (Courtesy, Perseus Books Group. Illustration taken from Charles Santore, The Windsor Style in America, Volumes 1 and 2 [1997; reprint, Philadelphia: Courage Books, 1981], 2: 94, fig. 75.) Like the chairs illustrated in figs. 11 and 12, this sack-back has arm knuckles with a large central lobe.

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1773. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, tulip poplar, maple, and mahogany. H. 53", W. 23" (seat), D. 17 1/2" (seat); seat height: 25"; seat depth/seat width: .761. (Courtesy, Carpenters’ Company of Philadelphia; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair was one of the speaker’s chairs used at the first Continental Congress when that group met at Carpenters’ Hall in 1774. Like the chairs illustrated in figs. 11, 12, and 20, this comb-back has arm knuckles with a large central lobe. The arms are mahogany.

Detail of the Windsor armchair illustrated in fig. 11 and a mid-eighteenth-century Delaware Valley armchair. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of Plan of the Improved part of the City [of Philadelphia] surveyed and laid down by Nicholas Scull, Esq. Surveyor General of the Province of Pennsylvania . . . published according to Act of Parliament Novr. 1st 1762 and sold by the Editors Matthew Clarkson, and Mary Biddle in Philadelphia. (Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.)

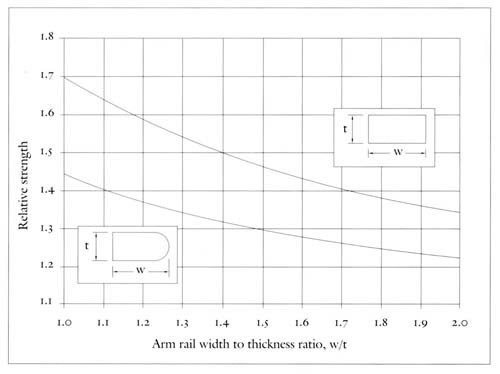

Graph showing the relative strength of flat-back, rectangular, and rounded rails. Results are generalized using the dimensionless parameter w/t where w is rail width and t is rail vertical thickness. The flat-back arm rail of the chair illustrated in fig. 8 is 1.004" wide and .612 " thick; its w/t ratio is 1.639 and its relative strength ratio is 1.275, making it about 27.5% stronger than a rounded rail of the same size. Had its rail been rectangular, it would have been about 43% stronger than a rounded rail of the same size.

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1773. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, tulip poplar, and maple. H. 37 1/4", W. 21 3/4" (seat), D. 16" (seat); seat height: 17 1/2"; seat depth/seat width: .737; rectangular rail width: 1.51"; rail thickness: .81"; arm support angle: 15°. Courtesy, Independence National Historic Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The only pins in the chair are those used to secure the hoop to the arm rail. This chair proves that Windsors with wide, strong rails were made in Philadelphia before the American Revolution.

Armchair, probably Massachusetts, ca. 1790. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, unidentified softwood, and maple. H. 38 1/2", W. 20" (seat), D. 15 3/16" (seat); seat height: 17"; seat depth/seat width: .787; rectangular rail width: 1.017"; rail thickness: .573"; arm support angle: 17.5°. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Of all the chair hoops examined for this study, the one on this chair is thickest in the center. The hoop tapers as it approaches the arm rail, which, like the arm supports, is quite thin. The seat does not have the usual channel next to the spindles.

Thomas W. Dewing (1851–1938), The Carnation, 1892. Oil on canvas. 20" x 15 5/8". (Courtesy, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, gift of Charles Lang Freer.) The lightness and elegance of chairs like the one illustrated in fig. 26 attracted American painters a century after they were made.

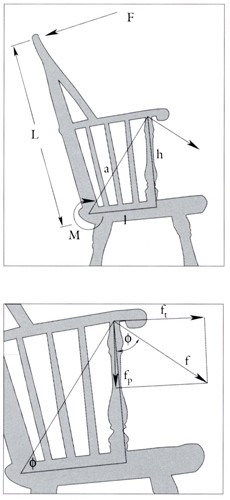

Diagram showing forces and movements created by a sitter leaning back on the chair illustrated in fig. 1. (Artwork, Wynne Patterson, Inc. from drawings by Martin Schnall.)

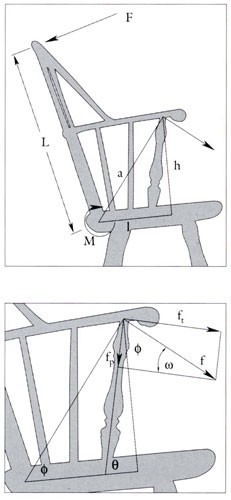

Diagram showing forces and movements created by a sitter leaning back on the chair illustrated in fig. 4. (Artwork, Wynne Patterson, Inc. from drawings by Martin Schnall.)

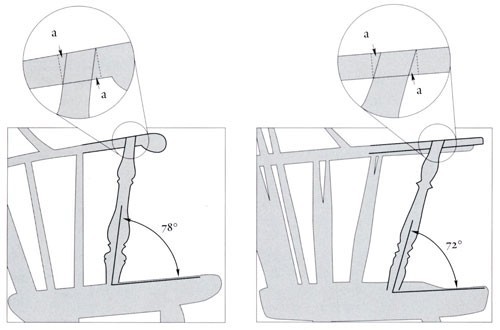

Diagram showing how an increase in the cant of the arm support increases the size of the barriers (a) the arm rail must clear before failing. Increasing arm rail thickness also increases the size of the barriers. (Artwork, Wynne Patterson, Inc. from drawings by Martin Schnall.)

Armchair, probably Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1760. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, tulip poplar, and maple. H. 35", W. 20 1/2" (seat), D. 15" (seat); seat height: 16 1/2"; seat depth/seat width: .736; rounded rail width: .924", rail thickness: .769" increasing to 1.099" near the middle spindle; arm support angle: 20.5°. (Courtesy, Independence National Historic Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The only pins in the chair are those used to secure the hoop to the arm rail. This chair proves that Windsors with strongly canted arm supports were made early on in Philadelphia or its environs.

Thomas Blackford, armchair, Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1785. Maple, oak, and hickory. H. 45", W. 21 1/2" (seat), D. 15 7/8" (seat); seat height: n.d.; seat depth/seat width: .718; rectangular rail width: .903"; rail thickness: .657"; arm support angle: 5–6°. (Courtesy, Winterthur Museum.) This chair, which was inspired by Philadelphia seating, indicates that Windsors with unpinned, nearly vertical arm supports were still made in Boston in the 1780s.

Lewis Bender, armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1795. Oak, hickory, maple, and tulip poplar. H. 36 1/2", W. 20 3/8" (seat), D. 15" (seat); seat height: 17", seat depth/seat width: .736; rounded rail width, rail thickness, and arm support angle not recorded. (Private collection; courtesy, Perseus Press.) This chair shows that Windsors with rounded arm rails and weakly canted arm supports were still being made in Philadelphia in the 1790s. On the other hand, the supports are relatively thin where they enter the seat, which reduces the risk of seat cracking.

Joseph Henzey, armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1785. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, unidentified softwood, and maple. H. 37 3/4", W. 21 3/4" (seat), D. 16" (seat); seat height: 17 3/4"; seat depth/seat width: .736; rounded rail width: .919"; rail thickness: .703"; arm support angle: 5°. (Courtesy, Independence National Historic Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Henzey’s Windsors are known for long baluster turnings, short tapered feet, and finely shaped seats, but structural analysis indicates that his chairs are weaker because their arm rails are rounded and arm support angles are weak. Since Henzey did not set up a large shop until after the Revolution, this chair and others suggest that he was using weaker construction methods after the war.

Armchair, possibly Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, unidentified softwood, and maple. H. 35", W. 20 1/2" (seat), D. 11 3/4" (seat); seat height: 16"; seat depth/seat width: .709; rectangular rail width: .953"; rail thickness: .582"; arm support angle: 12°. (Courtesy, Independence National Historic Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair has one of the shallowest seats of any object examined for this study. Like the sack-back illustrated in fig. 31, this chair shows that some early makers deviated from the Philadelphia standard.

Anthony Steel, armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1800. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, unidentified softwood, and maple. H. 37 1/2", W. 21 1/4" (seat), D. 15 5/8" (seat); seat height: 16 3/4"; seat depth/seat width: .927; rectangular rail width: .927"; rail thickness: .814", arm support angle: 9°. (Courtesy, Independence National Historic Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The chair is branded “A. STEEL.” The spindles are nailed at five places on the seat and three places on the rail. Nails are also found at the tops and bottoms of the arm supports and stretcher joints. If these nails are original, the chair proves that Windsors with stronger reinforced joints were being made in Philadelphia near the end of the eighteenth century.

Armchair, possibly Easton, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods and maple. H. 395/8", W. 21 5/16" (seat), D. 15 1/2" (seat); seat height: 16 1/2"; seat depth/seat width: .676; rectangular rail width: .995"; rail thickness: .744"; arm support angles: 6 and 8°. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This early, simply turned chair is stronger than most comparable Philadelphia examples. The tops and bottoms of the arm supports and all of the stretcher joints are pinned, and the spindles penetrate the seat like those on the Massachusetts chair illustrated in fig. 8. The fact that few Philadelphia makers used pins to reinforce their arm supports may explain why no tall sack-backs comparable to this example are known to have been produced in that city.

Detail showing the pins securing the right arm (from the sitter’s perspective) support of the chair illustrated in fig. 37. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of pinned stretcher joints on the armchair illustrated in fig. 37. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1765. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, unidentified softwood, and maple. H. 37 1/2", W. 21 1/2" (seat), D. 16 3/8" (seat); seat height: 17 1/2"; seat depth/ seat width: .736; rounded rail width: .985"; rail thickness: .674"; arm support angle: 10°. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This stylish chair displays the same structural weaknesses and damage found on the chairs illustrated in figs. 1 and 4: the hoop and rounded arm rail are cracked. The stretchers of this chair are not pinned. The feet have been extended.

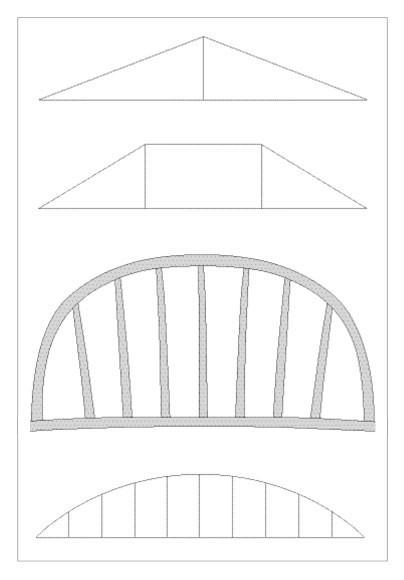

Drawing comparing the structures (from top to bottom) of a king post, queen post, Windsor hoop and spindle, and suspension truss. (Artwork, Wynne Patterson, Inc. from drawings by Martin Schnall.)

Armchair, Newport, Rhode Island, ca. 1770. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, unidentified softwood, and maple. H. 34 5/8", W. 21 1/2" (seat), D. 15 5/8" (seat); seat height: 14 5/8"; seat depth/seat width: .721; rectangular rail width: .941"; rail thickness: .633"; arm support angle: 20°. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair has pins or nails at all major stress points. All of the tall spindles penetrate the hoop and are wedged. The oversize rectangular hoop of this chair suggests that some early makers were aware of the problems of cracking hoops.

Detail of the pins securing the hoop and arm support on the left side (from the sitter’s perspective) of the chair illustrated in fig. 42. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, Massachusetts, ca. 1770. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, unidentified softwood, and maple. H. 34", W. 21 3/4" (seat), D. 16" (seat); seat height: 16"; seat depth/seat width: .724; rectangular rail width: .839"; rail thickness: .68"; arm support angle: 15°. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This chair originally had pins or nails at all major stress points. All of the tall spindles penetrate the hoop and are wedged. The hoop has extra length at the sides and becomes thinner as it tapers into the arm rail. The arm rail becomes thicker as it approaches the handholds, which provides additional strength and wood thick enough to shape the knuckles from the solid.

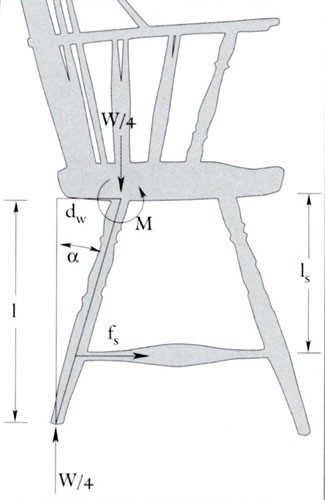

Diagram showing moments created in the undercarriage of a Windsor chair. (Artwork, Wynne Patterson, Inc. from a drawing by Martin Schnall.)

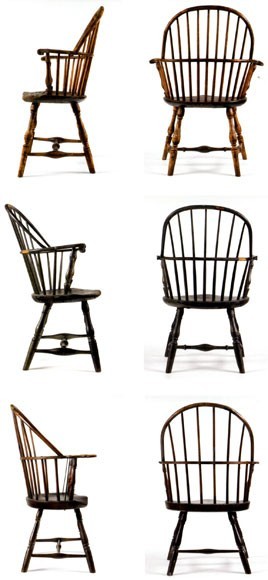

Overall views showing the armchairs illustrated in figs. 1, 4, 8, 11, and 26 from the side and rear. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Armchair, probably Boston, Massachusetts, ca. 1770. Unidentified ring-porous hardwoods, unidentified softwood, and maple. H. 36", W. 21 3/16" (seat); D. 16" (seat); seat height: 16 3/4 "; seat depth/seat width: .740; rectangular rail width: .936"; rail thickness: .676"; arm support angle: 10°. (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Although this chair was inspired by pre-Revolutionary Philadelphia seating, it has a fully rectangular rail, swelled feet, and a sculpted hoop above the arm rail. This chair also has equal leg splay like the New England Windsors illustrated in figs. 8 and 26.

Drawing comparing the tapered and swelled foot. (Artwork, Wynne Patterson, Inc. from a drawing by Martin Schnall.) The swelled foot was more than a New England stylistic convention. It allowed approximately 10 percent greater stretcher penetration and 10 percent greater stretcher diameter, which increased joint contact surface by about 20 percent.