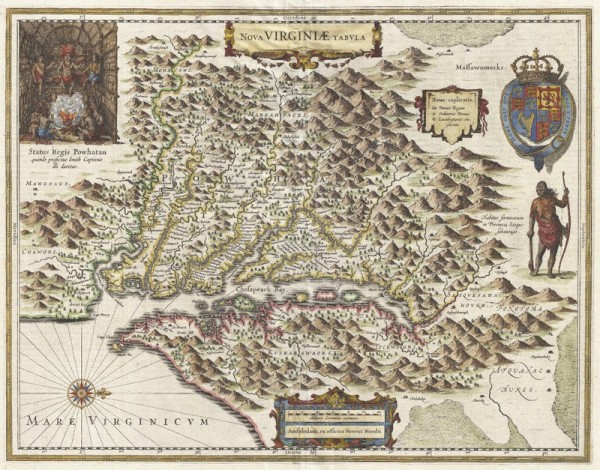

Henricus Hondius’s Nova Virginiae Tabula, map of the Virginia colony and the Chesapeake Bay, 1630. 15 1/2" x 19 1/2". (Geographicus Rare Antique Maps Cooperation Project.)

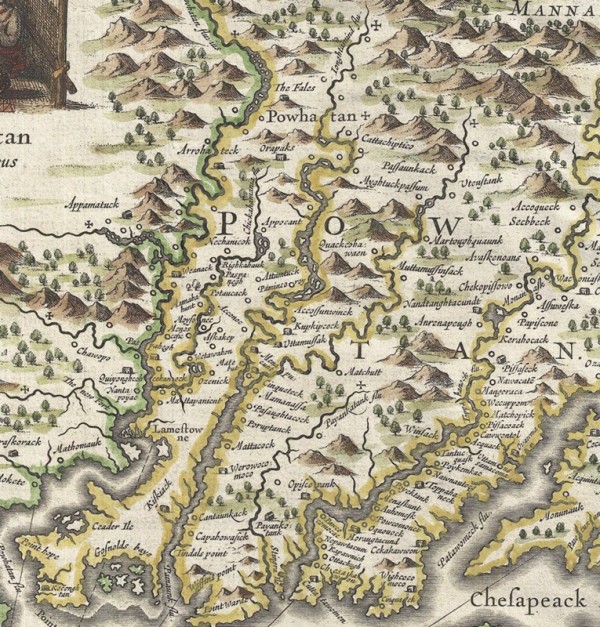

Detail of the map illustrated in fig. 1 showing the location of Berkeley Hundred. On March 22, 1622, Opechancanough, the paramount chief of the Powhatan Chiefdom, commenced a series of deadly surprise attacks on English settlements and plantations along the James River. More than three hundred colonists were slain, nearly a third of the young colony’s population. George Thorpe, an investor in the Virginia Company of London and a resident at Berkeley Hundred, was among the dead.

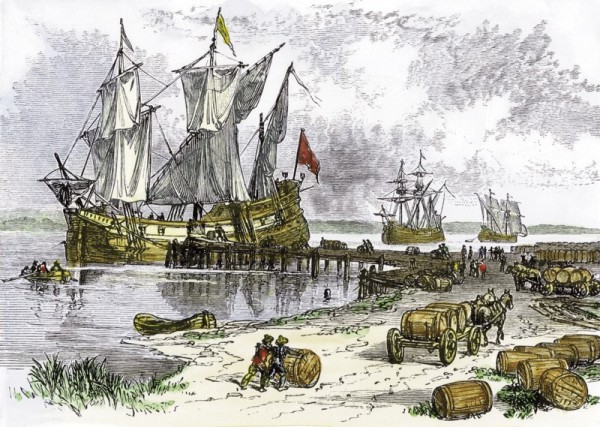

Anonymous, Sailing Ships Loading Tobacco at Jamestown in Virginia Colony, 1600s. Hand-colored woodcut of a nineteenth-century illustration, ca. 1880. (© North Wind Picture Archives / Alamy Stock Photo.) Archaeological research of the English settlements in Virginia—from the 1607 James Fort to the dispersed settlements that characterized the later seventeenth century—has revealed that individuals with the means to do so imported high-quality European and Asian ceramics to mediate the practical, social, and cultural aspects of their lives. The assemblages, largely transshipped from London and Plymouth, England, include wares that are uncommon in English households. Even the English coarse earthenwares, drawn chiefly from the potteries of London and Surrey-Hampshire, comprise many specialized shapes that are rare in contexts of the mother country.

Andries van Eertvelt, The Return to Amsterdam of the Second Expedition to the East Indies on 19 July 1599, 1610–1620. Oil on panel, 22" x 36". (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.) Dutch traders made significant inroads to the Chesapeake area in the first quarter of the seventeenth century by establishing close mercantile relationships with the English settlers in Virginia and Maryland. Colonists encouraged this trade, which was opposed by London merchants and the English government, because they could exchange tobacco for household and luxury goods at a much better rate than that provided by the mother country. This was the golden age of Dutch maritime, and commercial activities and merchants (some of them English factors based in the Netherlands) were engaged in the extensive movement of goods around the world. Many of the Chinese, Dutch, German, Italian, and Portuguese wares found on early Virginia sites can probably be attributed to Dutch traders, some of whom established trading posts in the colony.

Wine cup, Jingdezhen, China, 1600–1640. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 1 1/2". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) More than a dozen of these diminutive cups with flame-frieze decoration have been reported from early-seventeenth-century Virginia archaeological sites. These fine cups were once thought to be Imperial ware, reserved for use by the Chinese elite. Now they are recognized as status vessels made for export. They have been found on a number of Dutch shipwrecks (such as the Witte Leeuw, 1613, and the Hatcher, 1643) and terrestrial sites dating to the first half of the seventeenth century. This example was recovered from the Walter Aston Site, Charles City County, Virginia, in a 1630–1650 context.

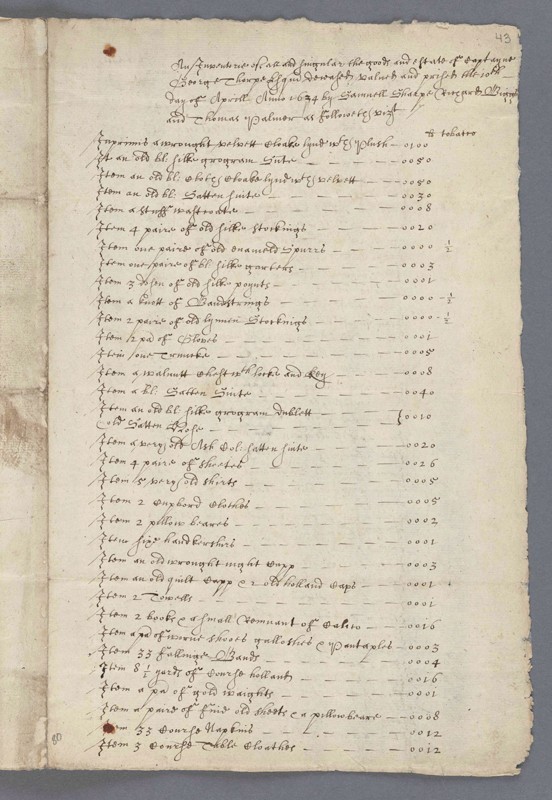

Dish, China, 1613. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 8 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This Chinese porcelain dish was recovered from the site of the Witte Leeuw shipwreck of 1613. Cargoes of porcelain wares were being received in Europe on Portuguese ships from the turn of the fifteenth century, and then by the Dutch trade in the late sixteenth century. Although not common and found only in households with high social status, examples have been found archaeologically on a number of early Virginia sites and are noted in probate inventories such as the “6 litle pursline [porcelain] dishes” in Thorpe’s inventory; see Appendix.

Dish, China, 1600–1620. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 12 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) Kraak porcelain was China’s first porcelain mass-produced for export to Europe. It was considered too coarse for the upper-class Chinese and too fragile for everyday use by the poor. The hand-painted designs, in underglaze blue only, are of landscapes and animals. Human figures are rarely depicted, making this porcelain suitable for Islamic markets as well. Buddhist and Daoist good-luck symbols make up the paneled border decorations.

Dish, Pickleherring potworks, Southwark, London, England, 1625–1630. Tin-glazed earthenware. D. 7 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) In decorating their wares, early London and Netherlandish tin-glazed potters adopted the popular style from late Ming porcelain of China’s Wan Li period (1573–1619). One of the most popular motifs, “bird-on-rock,” is shown on the central design of this dish and appears on English tin-glazed wares. Evidence of the early London tin-glazed dishes is relatively scarce in Virginia archaeological contexts of the first half of the seventeenth century.

Mug, Lisbon, Portugal, 1635–1660. Tin-glazed earthenware. H 3 3/16". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Portuguese tin-glazed wares are frequently found in early Virginia archaeological contexts. A parallel vessel to the mug shown here was found in York County, Virginia, and is associated with a high-status household that had dealings with merchants in the Netherlands. The Dutch trade may account for the presence of these mugs in Virginia, although parallels have also been found in Devon, England, an area of increasing commercial activity in the colony after the Virginia Company of London lost its charters for settlement in 1624. This example was excavated at Jordan’s Journey, Prince George County, Virginia, in a 1630–1650 context.

Floor tiles, Pickleherring potworks, Southwark, London, England, 1618–1650. Tin-glazed earthenware. Both are 5 1/4" square. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo on right, Robert Hunter.)

Excavated at Jordan’s Journey, Prince George County, Virginia, 1620–1635 context. These medallion tiles, one depicting a camel and the other a bird, are copies of earlier tiles produced in the Netherlands and reflect the influence of Christian Wilhelm, an immigrant potter from the Low Countries who established the Pickleherring pothouse in London. Decorative floor tiles such as these indicate high-style accommodations.

Apothecary jar, Aldgate, London or Netherlands, 1590–1610. Tin-glazed earthenware. H. 7 1/4". (Courtesy, Preservation Virginia; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Jars like this were produced in the Netherlands and were among the first tin-glazed earthenwares produced in England. The form developed in the Middle East as a container for medicinal substances, which also included spices and herbs that we may consider homeopathic remedies today. Apothecary jars are among the most common ceramic forms found on early-seventeenth-century archaeological sites in Virginia. This example was excavated from the James Fort in Jamestown, Virginia, 1607–1610.

Dishes, Northern Netherlands, 1620–1640. Tin-glazed earthenware with lead glaze on back. D. (left) 7 3/4"; D. (right) 7 9/16". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter). In the mid-sixteenth century, Italian potters introduced tin-glazed earthenware to the Northern Netherlands and early designs were borrowed from Italian maiolica. By the beginning of the seventeenth century, a distinctive Dutch style had developed in the region that relied heavily on geometric designs. Drug jars and dishes are the most common forms found in Virginia. These dishes were found at the Chesopean Site, Virginia Beach, Virginia, in a context roughly dating to the middle decades of the seventeenth century.

Dish base (front and back), Northern Netherlands, 1620–1640. Tin-glazed earthenware with lead glaze on back. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Contacts with China that developed after 1600 led to a movement away from the polychrome decorations of the Mediterranean to the blue-and-white motifs of the Far East. The undersides of these early dishes were lead-glazed in order to save the more expensive tin enamel for application to the upper surface. Many of the dish footrings are pierced to allow hanging. This and the lack of wear on the surface of some vessels suggest that dishes were not necessarily used for the consumption of food but to display status. This piece was excavated at the Chesopean Site, Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Storage jar, attributed to Thomas Ward, James City County, Virginia, 1620–1635. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 11 1/8". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Thomas Ward arrived at Jamestown in 1619 as the indentured servant to a bricklayer and is the first documented potter in the English colonies. The forms and styles of his vessels reflect a combination of the London-area redwares (like this thumb-impressed jar) and the products of the potteries on the border of Surrey and Hampshire counties. This example was excavated at the Nomini Plantation Site in Westmoreland County, Virginia.

Detail of the thumb-impressed rim on the storage jar illustrated in fig. 14. When the pot was thrown on the wheel, an extra coil was applied to reinforce the rim. The thumb impressions are both functional and decorative. This technique is also found on London redwares of the period.

Milk pan, Virginia, attributed to Thomas Ward, James City County, Virginia, 1620–1635. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 15". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Since the late sixteenth century, milk pans were used as settling vessels to separate cream from milk. The form was not common in Virginia before the large-scale importation of cows in the second quarter of the seventeenth century.

Dish, South Somerset, England, 1620–1630. Lead-glazed earthenware. D. 13 3/4". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) This dish with wet slip-sgraffito decoration has visual attributes that are characteristic of wares produced in the village of Donyatt in South Somerset. It is therefore considered a Donyatt-type, until chemical analysis of the clays can link it to a specific kiln in the well-known potting area of southwest England. Pottery from this region was arriving in Virginia before 1610, as ships embarking for the New World stopped in at Plymouth to avail themselves of goods they could acquire more cheaply than in London. This example was excavated at Jordan’s Journey, Prince George County, Virginia, in a 1630–1650 context.

Jug, South Somerset, England, 1600–1650. Sgraffito slipware. H. 8 3/8". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Meg Eastman, Virginia Historical Society.) English potters began producing sgraffito slipwares by 1600. The earliest examples are decorated with simple patterns of incised lines. The decoration became more elaborate over time, as demonstrated on a 1666–1690 bottle from St. Mary’s City, Maryland, decorated with birds and letters. This example was found at Jordan’s Journey, Prince George County, in a 1620–1635 context.

Cup and mug, Surrey-Hampshire border ware, 1600–1650. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. of cup 3"; H. of mug 4 1/2". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) These two drinking vessels were made in the potteries located on the Surrey-Hampshire border in England. For three hundred years beginning in the fourteenth century this area was a major source of quality utilitarian wares for the London market. Border wares in both everyday household forms and those with a specialized function—such as alembics, schweinetopfs, and double dishes—were part of the ceramic assemblage of the first Jamestown colonists in 1607. The earthenware has been found on seventeenth-century sites on the eastern North American continent from North Carolina to Newfoundland. These examples were found at Wills Cove, Suffolk, Virginia, in a 1630–1650 context.

Jug, Frechen, Germany, 1600–1620. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 3/4". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) Vessels from Frechen, a small village near Cologne, were the most widely traded German stonewares of the seventeenth century. While this wide-mouthed jug is undecorated, it is a form that was highly prized by English consumers, who mounted the necks and bases with silver. Fragments of these German vessels have been found on many early archaeological sites in the Tidewater region of Virginia.

Jug neck and body, Frechen, Germany, 1620–1630. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) These fragments are from a large Bartmann (“bearded man” in German) jug, also known since the seventeenth century as a “Bellarmine.” Shipped to Jamestown as containers for alcoholic beverages, these jugs are among the most common ware types found in early colonial contexts. The random accents of cobalt coloring on this vessel made it more costly than undecorated examples. These fragments were found at the Chesopean Site in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Schnelle fragments, Westerwald, Germany, 1600–1620. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Westerwald stoneware is commonly found in North American contexts dating 1620–1775, but it is rarely found in England prior to the second half of the seventeenth century. This suggests that the source of earlier Westerwald vessels in England’s colonies was a result of the extensive Dutch trade. The schnelle, or elongated tankard, form was first used in the sixteenth-century German potting industries in Siegburg and Raeren. It is seldom documented in colonial Virginia contexts. These fragments were excavated at the Chesopean Site in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Jug fragment, Westerwald, Germany, 1630–1650. Salt-glazed stoneware. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Stoneware products of the Westerwald continued to find their way into the Virginia colony throughout the seventeenth century. Mugs, chamberpots, and examples of these globular, big-bellied jugs are frequently seen in archaeological contexts. Relief decoration in the form of sprigged applied rampant lions and medallions is typical on these decorative but utilitarian wares. This example was found in Gloucester Point, Virginia.

Dish rim fragments, Germany, 1570–1630. Lead-glazed earthenware, with slip decoration. Top: Weser slipware; bottom: Werra ware. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) Both of these highly decorative German slipware types were exported in great numbers from Bremen to the Low Countries and from there to England in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The wares are found in small numbers on Virginia’s early-seventeenth-century archaeological sites, with Werra ware being much more common than Weser. These fragments were found at the Chesopean Site in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Weser slipware dish, Germany, 1570–1630. Lead-glazed earthenware, with slip decoration. D. 12 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Mark Heffron.) Weser ware was made in a number of production sites between the Weser and Leine rivers. Unlike Werra ware, Weser is a hard white fabric that was fired once. Designs are simple, consisting of geometric dots, lines, and squiggles in red-brown and green on a yellow ground. Weser ware is present but uncommon on early-seventeenth-century Virginia sites. Dishes comprised a major part of the industry’s output but hollow-ware forms have also been excavated: a small jug was found at Jamestown, Virginia, and a double-handled pot with rouletted decoration was located in Hampton, Virginia.

Werra slipware dish, Germany, dated 1620. Lead-glazed earthenware, with slip decoration. D. 13 1/8". (Private collection; photo, Mark Heffron.) This ware used to be known as Wanfried, for the village on the Werra River where large numbers of wasters were found in the late nineteenth century. Now kiln sites for the ware have been located more broadly along the river, with many biscuit wasters indicating that the vessels were fired twice. Dishes and bowls are most commonly found in Virginia on sites dating to the first quarter of the seventeenth century. The low-fired red fabric is decorated with white, green, dark brown, and yellow colors, with the central motif typically outlined in sgraffito. Common designs include flora, fauna, soldiers, and individuals holding wineglasses. Often the dishes are dated.

Dish fragments, North Holland, 1620–1650. Lead-glazed earthenware, with slip decoration. (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) German and Dutch potters were using a variety of slip decorating techniques in the early 1600s. The distinctive Dutch slip-trailed wares are sometimes found in American contexts of the 1630s–1660s. Two-handled drinking-bowl forms are known, in addition to broad dishes represented by these fragments found at the Chesopean Site in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Dish, North Holland, 1620–1650. Lead-glazed earthenware, with slip decoration. D. 10 7/8". (Private collection; photo, Mark Heffron.) The highly decorated Dutch slipwares usually have exuberant animal, bird, floral, pomegranate, and geometric designs. White slip, trailed directly onto the earthenware bodies, was often highlighted with splashes of green oxide beneath a clear lead glaze.

Bowl, northern Italy, 1575–1625. Sgraffito slipware. D. 9 3/4". (Courtesy, The National Park Service, Colonial Historical National Park; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Sgraffito slipware bowls and flanged dishes produced in Pisa, Italy, are found in Virginia contexts dating to the second and third quarters of the seventeenth century. The red alluvial clay is covered on the interiors of all forms with a thick white slip through which motifs are incised. Ocher and green copper oxide are used to highlight the design, which in Virginia is usually a flower or a bird, as shown here. This bowl was recovered from Jamestown Island, Virginia, in a second-quarter-of-the-seventeenth-century context.

Dish, Pisa, Italy, 1600–1650. Marbled slip-decorated earthenware. D. 10 5/8". (Courtesy, Virginia Department of Historic Resources; photo, Robert Hunter.) This ware, made in Pisa, is uncommon in England until close to the mid-seventeenth century. It frequently appears on Virginia sites earlier, which—like the other Italian, Netherlandish, and Portuguese wares—may be a result of the robust Dutch trade with the English colonies. Dishes and bowls are the most common forms. This dish, the center portion of which has been reconstructed, was excavated at the Chesopean Site in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Costrels, northern Italy, 1580–1650. Marbled slip-decorated earthenware. H. (left) 10 1/4", H. (right) 10 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Mark Heffron.) Fragments of these distinctive-looking wine flasks have been found in early Virginia contexts. The four molded lion’s-head lugs were meant to accommodate a strap or cord for suspension. The bichrome decoration of yellow and dark brown without the addition of green is considered to date to the later years of production. The narrow form of the example on the right is also a later shape.

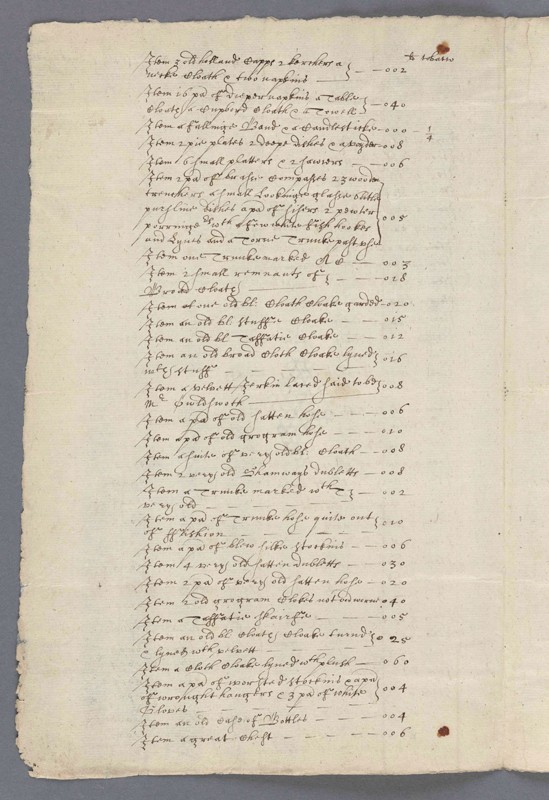

Page 1 of the Inventory of George Thorpe estate, Smyth of Nibley papers, 1613–1674. Manuscript, 1624. (Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations; photo, Diana Davies.)

Page 2 of the Inventory of George Thorpe estate, Smyth of Nibley papers, 1613–1674. Manuscript, 1624. (Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations; photo, Diana Davies.)

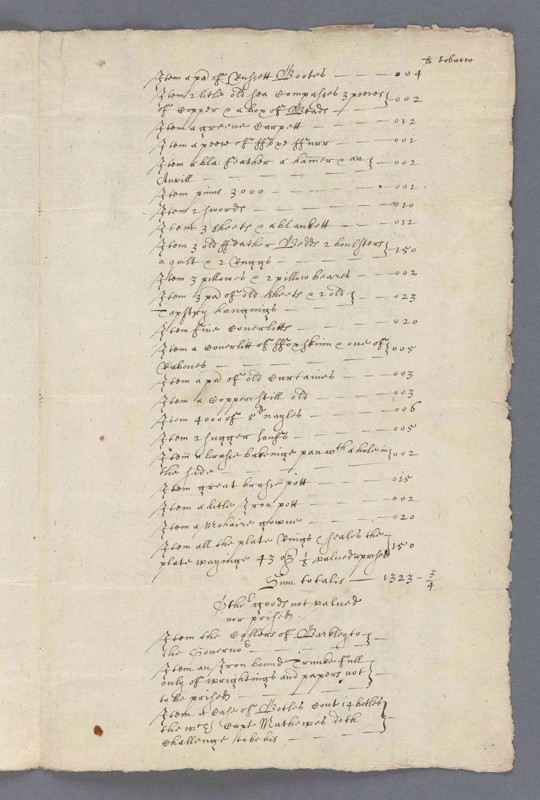

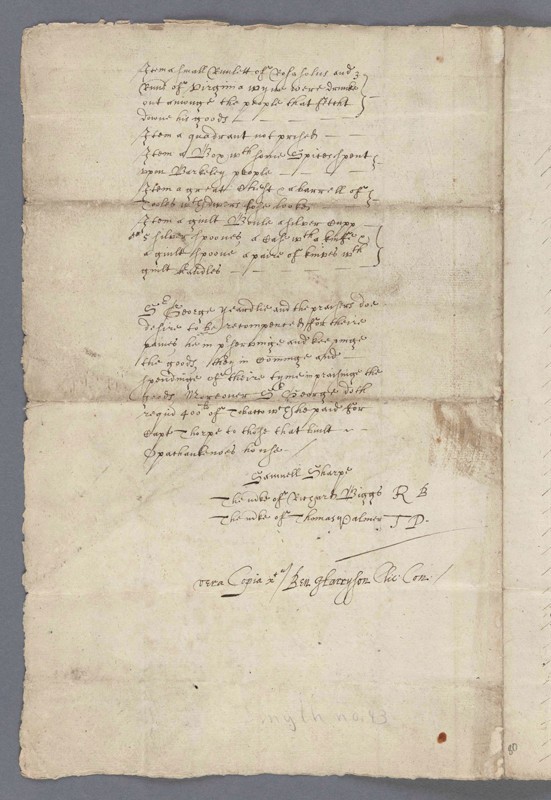

Page 3 of the Inventory of George Thorpe estate, Smyth of Nibley papers, 1613–1674. Manuscript, 1624. (Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations; photo, Diana Davies.)

Page 4 of the Inventory of George Thorpe estate, Smyth of Nibley papers, 1613–1674. Manuscript, 1624. (Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations; photo, Diana Davies.)