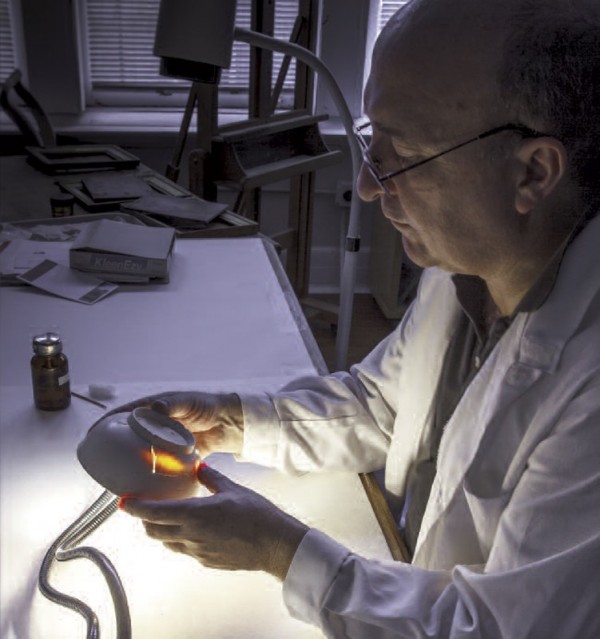

A white punch bowl is being examined and discussed in the archaeological laboratory of Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc., West Chester, Pennsylvania, February 2016. The ware type appeared to be an anomaly for Philadelphia archaeological contexts. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

A close-up of the bowl illustrated in fig. 1. Originally catalogued as a white, salt-glazed stoneware slop bowl with an unusual matte finish, subsequent physical spectrographic analysis revealed its composition to be aluminous-silicic ware—that is, a true or hard-paste porcelain. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

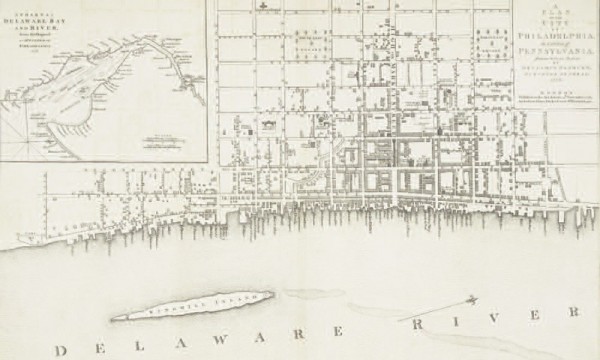

Plan of the City of Philadelphia, the Capital of Pennsylvania, from an Actual Survey by Benjamin Eastburn, Surveyor-General 1776. 19" x 26". Peter Andre (sculpt.). Andrew Drury, London, England, 1776. (The Huntington Library, San Marino, California 105:137 M.) The area under discussion is highlighted and detailed in fig. 14.

Section of brick-lined privy designated Feature 16. (Photo, courtesy Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc.)

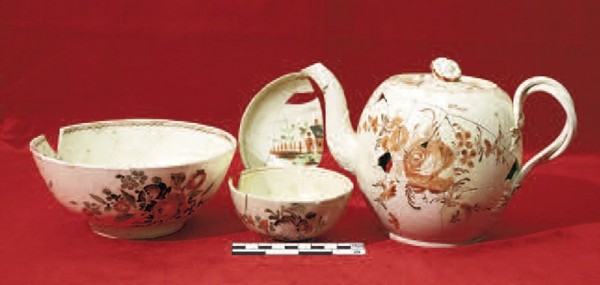

Porcelain teawares recovered from Feature 16. (Photo, Juliette Gerhardt.) The teabowls and saucers are Chinese porcelain and date to the 1760–1770 period. The center teapot is currently being analyzed.

English enameled creamware teawares recovered from Feature 16. (Courtesy, The Museum of the American Revolution; photo, Juliette Gerhardt.) These date to the 1770s.

Ceramic drinking vessels recovered from Feature 16. (Courtesy, The Museum of the American Revolution; photo, Juliette Gerhardt.) The lead-glazed tankards, bowl, and teapot fragments with the clear and black manganese glaze, which are of Philadelphia manufacture and date to the last quarter of the nineteenth century, represent the efforts of Philadelphia potters to compete with English refined wares.

Punch bowl, attributed to the American China Manufactory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1772. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, The Museum of the American Revolution; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the foot ring of the bowl illustrated in fig. 8.

Light passing through the bowl illustrated in fig. 8.

Detail of the surface of the bowl illustrated in fig. 8.

Punch bowl fragment, American China Manufactory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1772. Soft-paste porcelain. D. approximately 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a glassy glaze flaw on the rim of the bowl fragment illustrated in fig. 12.

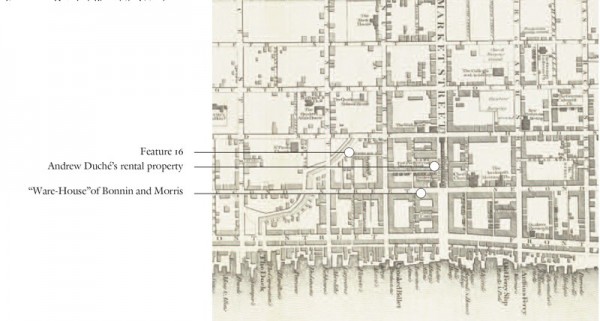

Detail of Plan of the City of Philadelphia illustrated in fig. 3, showing the location of Feature 16 at the site of the Museum of the American Revolution. The location of Andrew Duché’s rental property on Market Street is shown in relation to the “Ware-House” of Bonnin and Morris.

Sauceboat, American China Manufactory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770-1772. Soft-paste porcelain. H. 4", W. 3 1/2", L. 7 7/8". (Courtesy, Brooklyn Museum, gift of Daniel Berry Austin; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sauceboat, William Cookworthy, Plymouth Porcelain Works, Devon, England, ca. 1768–1770. Hard-paste porcelain. L. 6 1/8". (Courtesy, High Museum of Art, Frances and Emory Cocke Collection.)