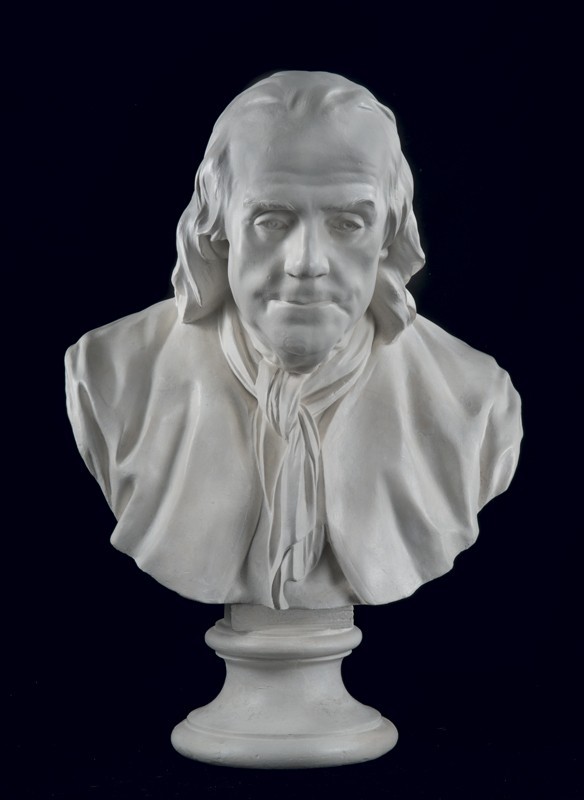

Bust of Benjamin Franklin, attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1779-1790. White pine; iron. H. 35", W. 21", D. 14 1/2". (Courtesy, Sotheby’s.)

Bust of Benjamin Franklin, attributed to William Rush, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1787. White pine. H. 20 1/4", W. 16 1/4", D. 13". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery.) According to Linda Bantel’s catalog entry in William Rush, American Sculptor (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1982), p. 97, this bust “has been in the collection of Yale College since 1804.” It was described as “a “Bust of Dr. Franklin carved by Rush. . . . taken from life . . . [and] presented by Dr. Franklin to his friend Isaac Beers Esq.”

Chimney back, Marlboro Furnace, Frederick County, Virginia, c. 1770. Cast iron. H. 34 1/2", W. 31". (Courtesy, United States Army Engineer Museum, Fort Belvoir, Virginia; photo, Robert Hinds.)

Pier table with carving attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, c. 1765. Mahogany with white oak; marble. H. 32 1/2", W. 62 3/4", D. 31 5/8". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Finial bust of John Locke, attributed to Martin Jugiez, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, c. 1770. Mahogany. H. 10 1/2". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the lion head on the pier table illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Pre-conservation oblique view of the bust illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Portrait bust of Antoninus Pius, Roman, 140-165. Marble. Dimensions not recorded. (© The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)

Finial bust, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, c. 1770. Mahogany. (Private collection; photo Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left eye of the bust illustrated in fig. 1. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left eye of the lion on the pier table illustrated in fig. 4. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the left eye of the bust illustrated in fig. 5. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Frontal view of the bust illustrated in fig. 1 with outer layer of paint removed. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

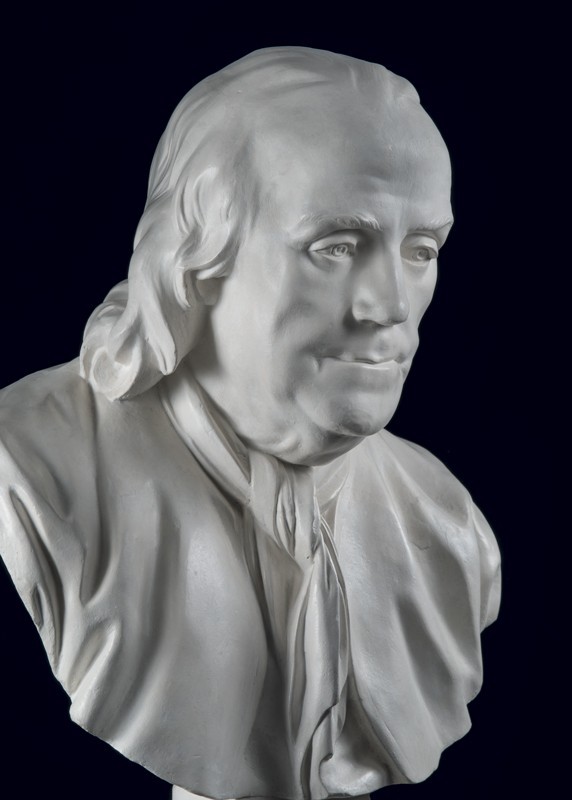

Jean-Jacques Caffieri, Benjamin Franklin, Paris, France, 1777. Terra-cotta. H. 27". (Courtesy, Biblioteque Mazarine; photo, Bridgeman Images.)

Jean-Jacques Caffieri, Benjamin Franklin, Paris, France, 1779–1805. Plaster. H. 28". (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society; gift of Dr. David Hosack.)

Oblique detail of the bust illustrated in figure 1 with outer layer of paint removed. (Photo, Scott Nolley.)

Oblique detail of the bust illustrated in fig. 15. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

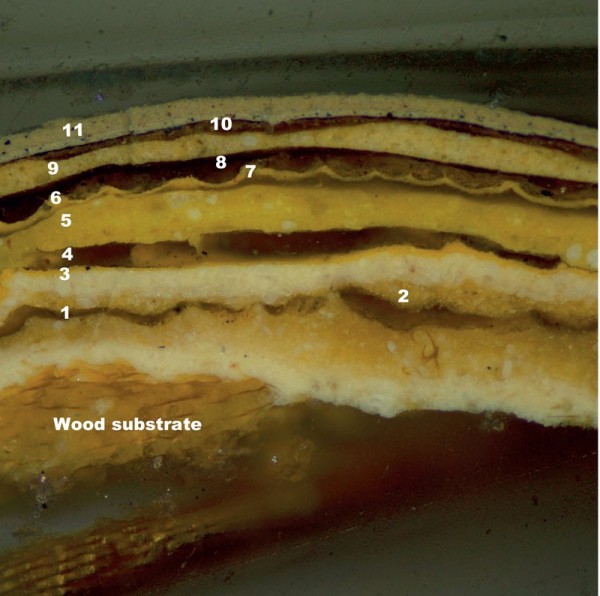

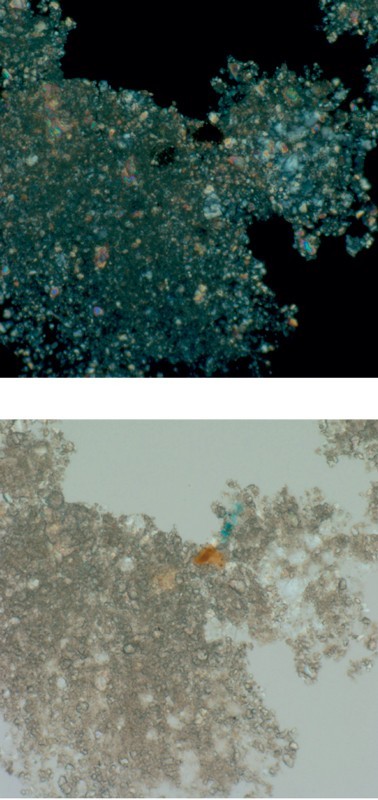

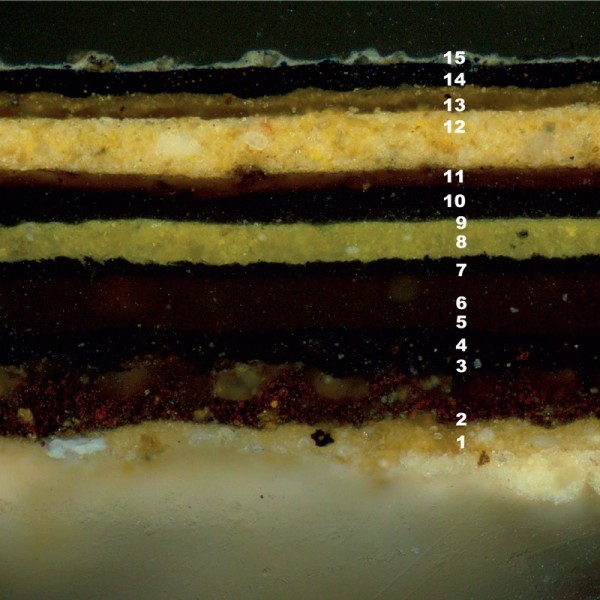

This cast sample from the interstices of the carved hair was photographed at 100x in reflected visible light. The cross-section reveals that there are 11 generations of varnishes and oil-based paints in the stratigraphy. The first generation consists of a grayish-white primer on top of the wood fibers at the bottom of the sample. There is a tannish base coat on top of this primer, followed by a gray glaze and a transparent varnish. There are remnants of gold leaf on top of a yellow base coat in the second generation. Gold leaf can be discerned on top of yellow base coats or varnishes in generations 2, 3, 4, 6, and 9. The varnish layers are transparent in reflected visible light, but are readily identifiable in reflected ultraviolet light. Bronze powder paint was applied in the tenth generation, and there are two applications of the most recent drab grayish paint at the top of the cross-section.

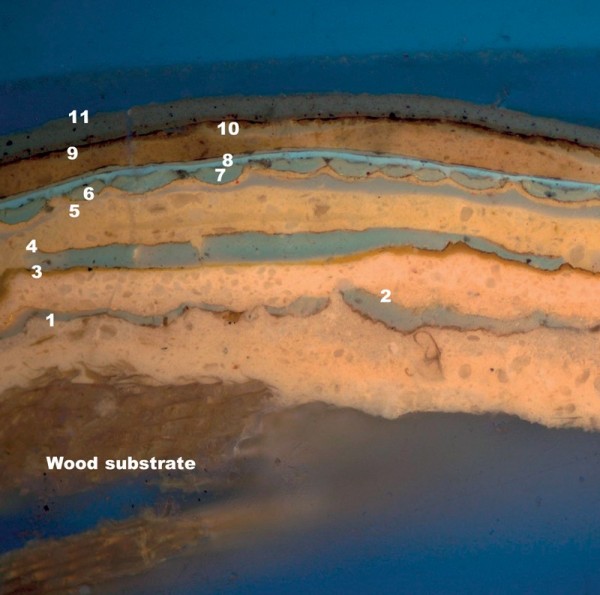

The cast sample from the interstices of the carved hair was also photographed at 100x in reflected ultraviolet light. The original pigmented grayish glaze on top of the tannish base coat is more obvious here than in reflected visible light. There are 11 generations of coatings in the stratigraphy, and there are plant resin varnishes in generations 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 8. These varnishes have a slightly quenched autofluorescence which is typical of natural resin-oil mixtures. The light bluish autofluorescence of the varnish applied in the seventh generation, on top of the sixth generation deeply cracked and dirty plant resin varnish, suggests it may be synthetic resin-based. The bright edges of the gold leaf layers in generations 2, 3 and 6 can also be seen where the leaf layers are turned over.

Pigments were scraped from the original base coat layer and analyzed at 1000x in plane polarized transmitted light, and with the polarizing light filters crossed for darkfield illumination. The pigments were identified based on their characteristic shapes, sizes and optical properties. The base coat was found to be made of a combination of tiny white lead pigments; larger translucent calcium carbonate particles; a few scattered burnt umber pigments; irregularly dispersed clumps of Prussian blue; and a few tiny sooty lampblack particles. These pigments are all consistent with eighteenth-century paints.

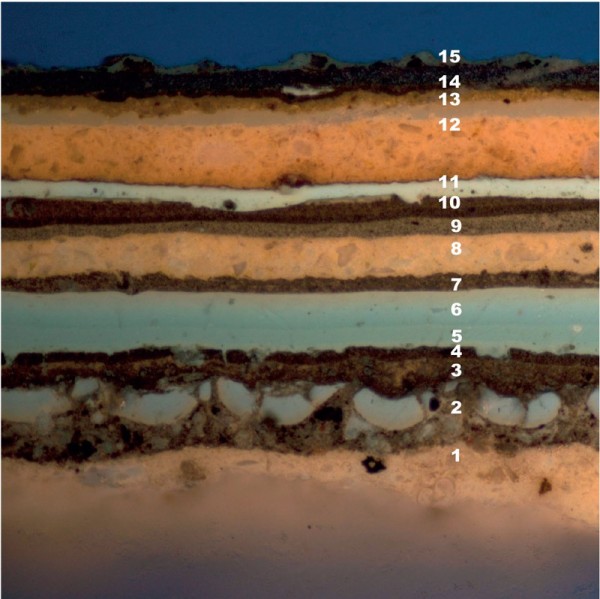

The evidence in the visible and ultraviolet light cross-section images photographed at 200x shows that earliest coatings from the base are damaged and disrupted, suggesting it was exposed to more exterior weathering and/or excessive heat than the bust. The comparative evidence indicates that the base was originally painted to match the rest of the sculpture, but it was subsequently painted dark brown, and then frequently repainted black or varnished. Fifteen generations of coatings were found on the base, compared to 11 on the bust, so perhaps it required more repairs or repainting because of exterior exposure. No gold leaf layers were found on the base.

The reflected ultraviolet light cross-section image at 200x from the base shows that the original tannish base coat and grayish glaze are more cracked and dirty than on the bust. There is a deeply cupped and cracked plant resin varnish on top of the brown paint in the second generation. This level of damage suggests the base was left exposed for an extended time to high heat and/or exterior weathering. After the second generation the base was painted black in generations 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, and 14, and varnished in generations 2, 5, 6, and 11.