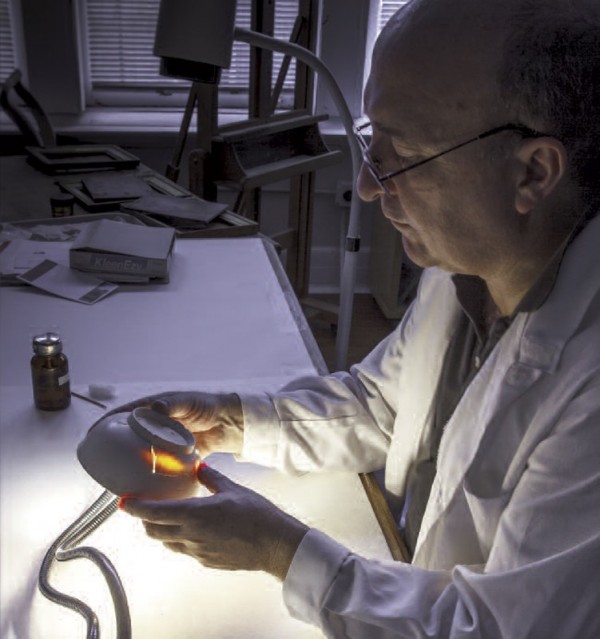

A white punch bowl is being examined and discussed in the archaeological laboratory of Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc., West Chester, Pennsylvania, February 2016. The ware type appeared to be an anomaly for Philadelphia archaeological contexts. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

A close-up of the bowl illustrated in fig. 1. Originally catalogued as a white, salt-glazed stoneware slop bowl with an unusual matte finish, subsequent physical spectrographic analysis revealed its composition to be aluminous-silicic ware—that is, a true or hard-paste porcelain. (Photo, Robert Hunter.)

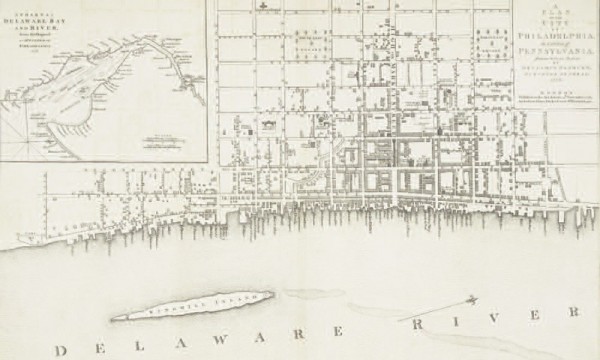

Plan of the City of Philadelphia, the Capital of Pennsylvania, from an Actual Survey by Benjamin Eastburn, Surveyor-General 1776. 19" x 26". Peter Andre (sculpt.). Andrew Drury, London, England, 1776. (The Huntington Library, San Marino, California 105:137 M.) The area under discussion is highlighted and detailed in fig. 14.

Section of brick-lined privy designated Feature 16. (Photo, courtesy Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc.)

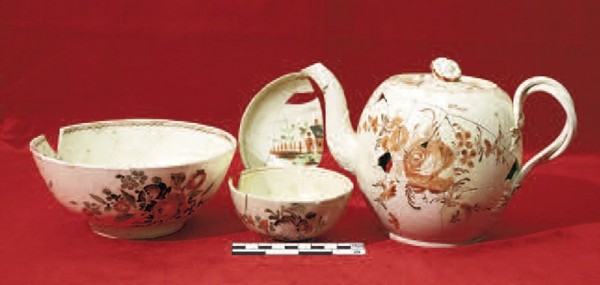

Porcelain teawares recovered from Feature 16. (Photo, Juliette Gerhardt.) The teabowls and saucers are Chinese porcelain and date to the 1760–1770 period. The center teapot is currently being analyzed.

English enameled creamware teawares recovered from Feature 16. (Courtesy, The Museum of the American Revolution; photo, Juliette Gerhardt.) These date to the 1770s.

Ceramic drinking vessels recovered from Feature 16. (Courtesy, The Museum of the American Revolution; photo, Juliette Gerhardt.) The lead-glazed tankards, bowl, and teapot fragments with the clear and black manganese glaze, which are of Philadelphia manufacture and date to the last quarter of the nineteenth century, represent the efforts of Philadelphia potters to compete with English refined wares.

Punch bowl, attributed to the American China Manufactory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1772. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, The Museum of the American Revolution; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the foot ring of the bowl illustrated in fig. 8.

Light passing through the bowl illustrated in fig. 8.

Detail of the surface of the bowl illustrated in fig. 8.

Punch bowl fragment, American China Manufactory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770–1772. Soft-paste porcelain. D. approximately 5 1/2". (Courtesy, Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, The Historical Society of Pennsylvania Collection; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of a glassy glaze flaw on the rim of the bowl fragment illustrated in fig. 12.

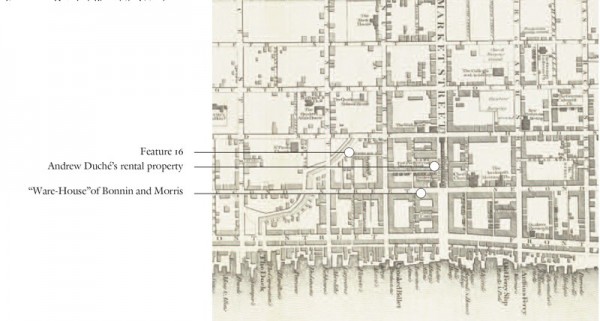

Detail of Plan of the City of Philadelphia illustrated in fig. 3, showing the location of Feature 16 at the site of the Museum of the American Revolution. The location of Andrew Duché’s rental property on Market Street is shown in relation to the “Ware-House” of Bonnin and Morris.

Sauceboat, American China Manufactory, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1770-1772. Soft-paste porcelain. H. 4", W. 3 1/2", L. 7 7/8". (Courtesy, Brooklyn Museum, gift of Daniel Berry Austin; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Sauceboat, William Cookworthy, Plymouth Porcelain Works, Devon, England, ca. 1768–1770. Hard-paste porcelain. L. 6 1/8". (Courtesy, High Museum of Art, Frances and Emory Cocke Collection.)

One of the most intriguing stories in world ceramic history is the search for the secrets of making hard-paste porcelain. First developed by Chinese potters around the seventh century A.D., these so-called true porcelains were later exported in huge quantities to a market of hungry consumers in the West, from the merchant class to the nobility.[1] The competition by Western potters to uncover the secret for making porcelain is usually told as a Eurocentric tale, centered on the romanticized exploits of Prussian alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger under the patronage of August the Strong, elector of Saxony and king of Poland.[2] Böttger’s research led to the opening of the Meissen porcelain factory near Dresden, which was producing hard-paste porcelain by 1710. Other European and British individuals and factories joined the race in the early part of the eighteenth century, but, lacking the knowledge of the materials and techniques discovered by Böttger, they had to make do with a variety of so-called soft-paste porcelain formulas.[3]

The primary distinctions between hard- and soft-paste porcelains are the ingredients used and the firing temperature necessary to vitrify the body, creating some degree of translucency. The formula for hard paste consists of kaolin clay mixed with feldspar and quartz, which is then fired to a temperature of about 1400°C (2552°F). Hard-paste porcelain is usually “once-fired,” meaning the non-lead glaze is applied to the raw clay body and then fired in a single episode. Soft-paste porcelains, which were made with compounds of white firing clays with added bone ash, glassy frits, or ground soapstone, required lower firing temperatures (in the 1100–1200°C range). Usually they are fired first to bisque temperatures and then subjected to a second glaze firing. Soft-paste porcelain glazes are typically lead-based.

Dozens of soft-paste formulas were devised during the eighteenth century in England at the factories of Chelsea, Bow, Liverpool, Worcester, Vauxhall, and Limehouse, among many others.[4] The products and histories of these factories have been the subject of countless collector and scientific studies.[5]

In America, the archaeological evidence for John Bartlam’s use of soft-paste porcelain at his manufactories in Cain Hoy and Charleston, South Carolina (ca. 1765–1772), has been recently published.[6] The soft-paste porcelain of the American China Manufactory of Philadelphia, ca. 1770–1772, continues to be the subject of scholarly research, articles, and exhibitions.[7] In his 1972 seminal study of the Philadelphia enterprise, Graham Hood suggested that the owners—Gousse Bonnin and George Anthony Morris, who were already successfully producing a soft-paste phosphatic porcelain—were also experimenting with a hard-paste porcelain body in 1772.[8] As evidence, Hood cited a Philadelphia news blurb that appeared in the Pennsylvania Packet on August 3, 1772: “that the Proprietors of the China Manufactory in this city, have lately made experiments with some clay presented to them by a Gentleman of Charlestown, South-Carolina, which produces China superior to any brought from the East Indies, and will stand the heat beyond any kind of crucibles ever yet made.”

Claims for an American discovery of the methods and materials required to make hard-paste or “true” porcelain have been associated as early as 1737 with potter and merchant Andrew Duché (ca. 1710–1778) and his ceramics exploits in Savannah, Georgia.[9] From the late 1730s onward, continued declarations emanated from Duché and other interested parties that the kaolin clay found in western North Carolina, known as “Cherokee clay,” was the crucial ingredient necessary to produce true porcelain. At the time of Graham’s writing, no domestically made specimens had surfaced to substantiate the claims of Bonnin and Morris or Duché, which led Graham to dismiss, cautiously, the claims of the former as hyperbole used in part to bolster public opinion for their failing soft-paste porcelain works. Exciting physical evidence has surfaced that reflects these “lately made experiments” in Philadelphia.

A small, white bowl (fig. 1) was recovered in 2014 from an eighteenth-century archaeological context at the site of the proposed Museum of the American Revolution (MoAR) in the Old City section of Philadelphia. It was among nearly 85,000 artifacts found in excavations conducted by archaeologists from the Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc.[10] Initially thought to have a stoneware body, subsequent material analysis by J. Victor Owen and his colleagues has revealed that the bowl is true, hard-paste porcelain, and most likely of Philadelphia manufacture (fig. 2). Their findings are presented as a companion article, appearing next in this volume.[11] The present discussion chronicles the American quest for making true porcelain and frames the archaeological and historical context of the discovery of this incredibly significant artifact.

The American Pursuit of the Secrets of Hard-Paste Porcelain

The American porcelain story begins with the Duché family of Philadelphia. The family’s progenitor, Anthony Duché, a Huguenot émigré, and his sons began making lead-glazed earthenware and salt-glazed stoneware in Philadelphia in the 1720s. His stoneware and earthenware products are known only through archaeological examples, but he was an extremely prolific and proficient potter.[12]

One of Anthony’s sons, Andrew, took an interest in expanding the family pottery business southward and circa 1734 moved to the growing metropolis of Charleston, South Carolina. The history of Andrew Duché has been recounted by several ceramic historians throughout the twentieth century but is perhaps best summarized in the 1991 comprehensive article by Bradford Rauschenberg, former director of research at the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.[13] His compilation of information known about Duché’s life forms the basis of the summary presented below.

Once in Charleston, Duché wasted no time in building a kiln and advertising to the public in 1735 the availability of “Butter pots, milk pans, and all other sorts of Earthenware.”[14] Unfortunately, no physical evidence of Duché’s kiln or pottery from those years has come to light; from records, however, we do get the sense that he was no mere potter but an astute businessman who clearly had an interest in creating more than pots and pans for the local market.

It was around this time that the Chinese secrets of porcelain manufacture were made known to the Western public. A series of letters written by Jesuit missionary Père d’Entrecolles, who had surreptitiously observed porcelain works in China from 1710 to 1722, was published by Jesuit historian Jean Baptiste Du Halde, first in a French edition in 1735, and a year later in English. Of crucial importance, d’Entrecolles identified the two key ingredients of the Chinese true porcelain: “Petuntse” and “Kaulin.”[15] Petuntse, also known as china stone, was a widely available feldspar mineral. However, sources for the more essential kaolin were relatively unknown to English and American potters at this time.

That was to change in 1737, when Duché moved to New Windsor, Georgia, a settlement along the Savannah River located, notably, in the center of the lucrative Cherokee Indian trade. At this time, he probably became aware of the fine white clay from their territory in western North Carolina, a substance the Cherokee called unaker.[16] For the Cherokee, unaker had a ritual significance and was used for making their white clay pipes and even used as a whitewash for their wattle and daub houses. Duché recognized the Cherokee clay as kaolin.

In its first two decades, 1732–1752, the Georgia Colony was governed by a board of trustees created by the British Parliament. The colony’s commander, General James Oglethorpe, had enticed Andrew to bring his craft to the new colony of Georgia, giving him land and arranging for the trustees to provide him with funding. In 1738 Duché moved to the growing town of Savannah, Georgia, and set up a pottery there.

Much of what we know about Duché’s activities in Savannah comes from a series of letters written by William Stephens, secretary to the trustees. One such letter, written in 1738 in support of the potter’s efforts, confirmed that Duché had produced “2 Kilns of handsome Ware, of various kinds, Pots, Pans, Bowls, Cups, & Jugs.”[17] Duché was successful at producing stoneware and earthenware, and archaeological evidence has confirmed that his salt-glazed stoneware was on the same high level as his family had produced in Philadelphia.[18] But he had greater aspirations than simply producing crockery. In the same 1738 letter, Stephens also wrote that Duché had made a “small Teacup of Which he shewed me when held against the Light, was very near transparent.”[19] Of course this was big news for the trustees, since it suggested that Duché had made use of the Cherokee clay and had discovered the methods of porcelain making. While it is unclear whether Oglethorpe had actually seen these porcelain specimens or was just relying on the reports of Stephens, he nevertheless passed on to his superiors in London the information that “clay had been found here that a Potter has bak’d into China Ware.”[20]

Those back in England were very excited, especially the president of Georgia’s board of trustees, the Earl of Egmont, who resided in London. Egmont was instrumental in encouraging Duché, enthusiastically but vastly overstating that “He is the first Man in Europe, Africa, or America that found the true material and manner of making porcelain.”[21] Egmont sent samples of Chinese porcelain to Duché for use as models. In response, Duché asked for a patent for his product; he did not receive one, but did acquire additional funding. Duché continued to experiment for another two years but seems not to have produced a final porcelain product—much to the consternation of his supporters.

The story of Andrew Duché in Savannah is eventually one of frustration and self-destruction. Although the trustees gave him money and encouragement, he complained bitterly and made endless excuses for his lack of success with the porcelain body. He became a political malcontent who criticized the way the trustees managed the colony. Secretary William Stephens, initially a supporter, eventually lost patience with Duché, pronouncing that the potter had become “a little too much addicted to Politicks” and that, as a result, his porcelain pursuits had become inconsequential.[22]

In spite of all the rhetoric, hype, materials, and funding provided by the trustees, it has remained unproven whether Duché was ever actually successful in producing a true porcelain body while in Savannah. It is also uncertain whether Duché himself had visited the Cherokee kaolin mines or whether he had developed agents through his business as an Indian trader—without question, though, he had quantities of the Cherokee kaolin at his disposal. By the 1740s other interested parties in England and in the colonies had become aware of the valuable white clay deposits in the Cherokee region of the North Carolina mountains.

By 1742 Duché was still irritating the trustees, owing them money and porcelain, and making several unsuccessful attempts to leave Georgia. On one occasion he was caught sneaking out of Savannah on a boat loaded with “divers chests, casks, & other effects.”[23] Duché finally left Georgia in February 1743 and arrived in England in May to meet with his primary supporter, the Earl of Egmont. On September 23, 1743, Duché delivered a long letter to the trustees, rehashing his complaints and political entanglements.[24] Little else is recorded about Duché’s extended time in England, although two very important events suggest that he was sharing his secrets of porcelain making with all who would listen.

Most notably, on December 6, 1744, a British patent was filed by “Edward Heylin of Bow in the county of Middlesex, merchant, and Thomas Frye of the parish of West Ham in the county of Essex, painter . . . for the production of porcelain from an earthy mixture.”[25] The material cited “is an earth, the produce of the Cherokee nation in America, called by the natives unaker.”[26] Scholars have argued that this patent is directly connected both to Duché’s porcelain experiments in Savannah and to his subsequent journey to England.[27] Evidence for the success of this patent has been ascribed to twenty-seven surviving examples referred to by scholars as the “A”-marked group.[28]

In May 1745 British potter William Cookworthy wrote that he had been visited by “the person who hath discovered the china-earth.” Cookworthy added that his visitor “had several examples of the china-ware of their making with him, which were, I think, equal to the Asiatic.” According to Cookworthy’s letter, using the language of d’Entrecolles, this person had discovered “both the petunse and kaulin” while searching for mines “in the back of Virginia” and that this kaolin is “the essential thing towards the success of the manufacture.”[29] Duché is generally identified as this individual who must have sought out Cookworthy during his 1744 trip.[30] Cookworthy would later discover his own source of china clay in Cornwall, and then, in 1768, his own method for making England’s first successful hard-paste porcelain.[31]

Duché returned to Charleston by January 1745 and continued to develop his trade in the Cherokee territory ostensibly to secure a regular supply of the kaolin. He went so far as to petition the South Carolina Assembly for consent to build a 300-mile road between Charleston and the Cherokee territory, possibly to ease the overland shipping of clay.[32] The effort to obtain funding for the road was unsuccessful and Duché eventually left the Carolinas about 1748 and moved to Norfolk, Virginia, continuing as a merchant but apparently forsaking interest in the porcelain-making business. For the next fifteen years, however, other individuals picked up where Duché left off and made shipments of the Cherokee clay to England. A summary of those shipments is presented below.[33]

1747—Robert Pringle, a Charleston merchant, shipped “1 Bag White Clay” to his brother in London.[34]

1755—Dr. Alexander Garden, a Charleston physician and naturalist, “penetrated into the indian country and formed a treaty with the cherokees in their own mountains.” He shipped samples to Worcester.[35]

1757—Henry Laurens, a wealthy and influential Charleston merchant and rice planter, wrote to Thomas Mears of Liverpool: “We will send by the first opportunity that shall present for 2 or 300 lb weight of the Cherokee Clay.”[36]

1759—Dr. Alexander Garden procured some more of the “different layers of Savannah West Bluff” and sent a sample to London.[37]

1764—Henry Laurens wrote to Andrew Williamson of Ninety-Six, South Carolina: “I am applied to by a particular friend to procure a Specimen of our Cherokee Clay for making potters fine Ware. Can you help me at any reasonable expence & soon to the quantity of a Flower Barrel full.”[38]

1765—Caleb Lloyd of Charleston sent his brother-in-law Richard Champion, a Bristol merchant and porcelain developer, “a box of Porcelain Earth which I have sent you by this vessel to be forwarded to Worcester to the Proprietors of the China Manufactory there, to have a few pieces of china made of it for me, agreably to a List I enclose. I have desired them to spare no expense about it, and to send it to you to be forwarded to me. It was at considerable pains and expence this Earth was procured. It comes from the internal part of the Cherokee Nations, 400 miles from hence, on mountains scarcely accessible.”[39]

Clearly, the clays mined from the Carolinas were an important catalyst in the development of successful porcelain formulas for the earliest English porcelains. In the midst of various parcels of American clay being shipped to England, master Staffordshire potter John Bartlam arrived in Cain Hoy, South Carolina, circa 1765. Bartlam’s arrival got the attention of English potter Josiah Wedgwood, who was worried that the defection might affect his American business. Although not known for his interest in porcelain, Wedgwood was fanatically concerned about any new ceramic materials that he did not have access to or control over. Not wanting to miss an opportunity, in 1767 he commissioned an English agent named Thomas Griffiths to sail to America and obtain a quantity of Cherokee clay.[40] Wedgwood did not find an immediate use for the kaolin, but eventually he incorporated it into some of his jasperware formulas, primarily to take advantage of the hype around the material’s mysterious associations.[41] Even though Wedgwood might have been interested in pursuing a regular supply of the Cherokee clay, he was certainly put off by the high cost as well as the outbreak of the American Revolution. He lost all interest in American kaolin after gaining access to a supply from Cornwall on the southeast coast of England, a figurative stone’s throw from Wedgwood’s factory in Staffordshire.

Just before John Bartlam began producing creamware and his version of a phosphatic soft-paste porcelain in Cain Hoy and later Charleston, South Carolina, Andrew Duché again went back to England in 1763, moving from Norfolk to Bath.[42] The historical record is again frustratingly mute regarding Duché’s extended time there. While he was in England, however, English potter William Cookworthy, after years of experimentation, received a patent for porcelain manufacture on March 17, 1768.[43] This discovery became the basis for the establishment of the Plymouth and Bristol porcelain factories, which produced the first successful true porcelain in England.[44] Although there are no records to connect Duché to Cookworthy’s patent application, the timing is probably not sheer coincidence.

Duché returned to America and his home in Norfolk in early 1769, and almost immediately announced that he was leaving the Virginia colony to return to his hometown of Philadelphia. His relocation to Philadelphia—the epicenter of American porcelain production in 1769—coinciding with the opening of Bonnin and Morris’s American China Manufactory in 1770 has, of course, been noted by researchers.[45]

The arrival of Duché in Philadelphia also coincides with Henry Laurens’s shipment of Cherokee clay from Charleston. Laurens’s letter of November 28, 1771, to William Williamson of London states that he “put a Keg of Clay with one of my own into the hands of Mr George Morris, the Manager or one of the principal Managers of the China Manufactory in Philadelphia.”[46] The arrival of Carolina clay at the Bonnin and Morris works is confirmed by the Pennsylvania Packet on August 3, 1772.[47] With that notice, the historical evidence places together in Philadelphia the necessary ingredient of porcelain making (Cherokee unaker), the expertise of Andrew Duché, and the desire of the proprietors of the American China Manufactory to produce “China superior to any brought from the East Indies.”

The Archaeological and Historical Context of the Bowl

The Old City section of Philadelphia is its earliest area of settlement, dating back to the city’s founding in 1682. The city, which was laid out in a standard grid, developed distinct neighborhoods (fig. 3). The Old City became Philadelphia’s mercantile and political center during the eighteenth century and remains one of the most historic areas in America. Adjacent to Philadelphia’s wharfs, the surrounding blocks were home to merchants, tradesmen, shipbuilders, and private residents. Taverns were among the most active businesses. Benjamin Franklin had his print shop and residence on the main road known as High Street, later renamed Market Street. Notable Philadelphia craftsmen, among them chairmaker William Savery, were located there.

Since the 1960s, large-scale archaeological excavations have been conducted in advance of block-wide redevelopment projects in downtown Philadelphia.[48] Most recently archaeological investigations by crews from Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc. spent months recovering artifacts from the site of the proposed Museum of the American Revolution (MoAr), located at 3rd and Chestnut Streets (see fig. 3). That investigation identified a total of fifty features, including foundations and brick-lined shafts. Of particular interest were four privies that dated to various parts of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. These features contained an enormous quantity of ceramics including locally made Philadelphia objects and imported English, German, and Chinese wares, among other artifacts.

The punch bowl was recovered from deposits in Feature 16, a brick-lined privy shaft (fig. 4). The privy was associated with a house that had been built on the south side of Carter’s Alley in 1753 by Nathaniel Goforth. The digging of that privy may date to that period of use, but when it was filled in the 1780s, the house belonged to Mary and Benjamin Humphreys, a Quaker couple who lived there from 1776 to 1813. A deed for the property shows that the shaft was “now filled up” as of July 13, 1789, by which time an adjacent privy, Feature 12, was constructed.[49]

The Humphreys appear to have operated an unlicensed tavern from the house, which certainly accounts for the incredible quantities of ceramic and glassware found in the privy fill.[50] A minimum of 364 ceramic and 220 glass vessels were mended from 23,202 artifacts recovered in Feature 16. The artifacts include 18 tankards in different sizes (pint, half-pint, quarter-pint), 38 drinking glasses of one kind or another, 7 punch bowls, 8 jugs or bottles, 3 decanters, and 103 bottles, most of them for alcohol. Besides the drinking vessels and bottles, other artifacts found in the Humphreys’s privy—29 slip-decorated pie dishes and chargers, 13 teapots, 6 porringers, 11 bowls, and 23 chamber pots—resemble artifacts found elsewhere in association with Philadelphia taverns. In addition, 73 tobacco pipe fragments and 107 buttons were recovered, quantities typically associated with tavern sites. The large number of chamber pots, in particular, suggests that the tavern may also have functioned as an inn. Figures 5–7 illustrate the variety of refined teawares and drinking vessels found among the mix of large quantities of redware, creamware, and Chinese export porcelain.

The porcelain bowl was initially cataloged as circa 1760 white salt-glazed stoneware assumed to be of British manufacture (fig. 8). An unusual matte finish to the glaze was noted but the surface lacked the characteristic orange peel appearance of salt-glazed stoneware. Subsequent examination confirmed that it was not stoneware but a previously unseen porcelain type in Philadelphia’s archaeological contexts. It is more than 90 percent complete, having shattered into nineteen pieces when it was discarded into the privy. With a trimmed foot ring, the profile of the bowl conforms to the Chinese export porcelain shapes adopted by British potters in the second half of the eighteenth century (fig. 9).

After the initial visual determination that the bowl was an unidentified porcelain body rather than stoneware, a small sample was taken from one of the nineteen fragments and submitted for analysis to J. Victor Owen of the Department of Geology at St. Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia. His results showed that the composition of the bowl was a true, hard-paste porcelain with a non-lead glaze; he and his team have also determined that the bowl was once-fired, having been glazed in the raw state. Although the bowl clearly lacked any underglazed decoration, conservator Scott Nolley subsequently examined it for possible remnants of overglazed enamels, which might have become fugitive in its buried context. No such evidence was found.[51] Nolley reassembled the bowl to contemporary museum standards and further confirmed the translucency of the body with directed light sources (fig. 10).

Discussion

The discovery of a true porcelain bowl in a brick-lined privy in the Old City section of Philadelphia is a thrilling addition to the mounting evidence for the history of porcelain making in eighteenth-century America. The undecorated porcelain bowl, found among numerous other Philadelphia ceramics, appears to be of local Philadelphia manufacture. The bowl retains visible turning or production marks and has numerous imperfections in the clay body (fig. 11). The sheen of the glaze is barely noticeable and the materials analysis suggests that it is under-fired. It cannot be mistaken for Chinese porcelain or fully finished examples of eighteenth-century Plymouth or Bristol porcelain.

The American China Manufactory in Philadelphia was a short-lived venture that opened in 1770 and was closed by 1773. Despite attempts to keep the operation afloat, the property was sold in 1774. It was a period of considerable experimentation and adaptation to both material and economic factors. For years, various scholars have suggested that Bonnin and Morris were attempting to create a true porcelain body in addition to their phosphatic and glassy frit formula. Evidence for their phosphatic soft-paste body is found in the various advertisements for the factory seeking large quantities of cattle and beef bones as well as physical confirmation by Victor Owen’s analysis.[52] The initial workers hired for the Philadelphia venture were brought in from the Bow factory in London, which used a very similar soft-paste formula. Owen’s examination of an openwork basket in the collection of Colonial Williamsburg with the inscription “23 April 1773” has provided proof positive of the Philadelphia factory’s change in formula to produce a glassy frit, lead-bearing, non-phosphatic paste.[53]

Remarkably, the initial cataloging of the bowl as English white salt-glaze corresponds nearly identically with the 1741 observation made by the Georgia trustee secretary William Stephens. On August 17 of that year Stephens watched Duché turn some “useful cups . . . about the size of large Tea-Cups.” He further noted that their “present Appearance differs very little (if any Thing) from some of our finest Earthen-Ware made in England.”[54] The finest English wares of that period would have been the white salt-glazed stoneware being produced in Staffordshire and exported throughout the Western world.

The lack of decoration on the bowl, which might simply reflect the experimental nature of the object, also corresponds with another of Stephens’s commentaries. Stephens noted that Duché himself admitted that “Glazing, and Colouring, is a peculiar Work, to be done by other Hands, who are Artists in that way.”[55] So if Duché was not making decorated porcelain in Savannah in the 1740s, either lacking the knowledge or the interest, this trend may have continued if he was once again at work in Philadelphia in the 1770s.

If the bowl is not a product of Andrew Duché or the Bonnin and Morris factory, what are alternative explanations? Could the bowl be an example from a post-1774 attempt at making American porcelain? The privy context in which the bowl was found contains numerous other examples of tea- and tablewares that date to the early to mid-1770s, and the privy was known to have been filled by 1789. One putative attempt to produce hard-paste porcelain in eighteenth-century Philadelphia was recorded in August 1783: that an unidentified “French regimental surgeon” was attempting to make a “porcelain fabrick” using clays obtained in Maryland and that “some small samples had been fused very successfully . . . but many difficulties are yet to be overcome.”[56] No further evidence of this apparently failed attempt is known. Another eighteenth-century mention comes from the Philadelphia city directories in 1795 and 1796: the entry of a Samuel Faulkner as a china manufacturer at 91 North Sixth Street—the operative word “china” equating with porcelain—but nothing further is known.[57]

Given the current evidence for dating the age of the punch bowl based on its archaeological context, its size and shape, and the absence of another likely American porcelain maker, we believe that the porcelain bowl is a creation of the 1772 experimentation with the Cherokee clay sent by Henry Laurens from Charleston, South Carolina. There is little to suggest that the production of hard-paste porcelain in Philadelphia went beyond limited production. The analysis by Owen and his team shows that the bowl is relatively under-fired and did not reach the temperature necessary to fully vitrify the hard-paste admixture.[58] While Bonnin and Morris may have acquired the appropriate materials and knowledge for their preparation, they might not have possessed the kiln technology to consistently reach the 1400°C level needed for hard-paste porcelain.

Another explanation for not pursuing production is that the partners did not have a steady source of the Cherokee clay to supply the quantity needed. With the financial failure of the factory looming in 1773, Gousse Bonnin abandoned Philadelphia and sailed to England. George Morris had already left Philadelphia, in 1772, to travel to North Carolina, where he died on October 5, 1773, from a “bilious fever.” Diana Stradling has suggested that Morris could have been in North Carolina to make arrangements for acquiring a regular supply of the Cherokee clay—an intriguing speculation, but no other information has been found to support such an endeavor.[59]

We have to consider how an experimental object like the punch bowl could have ended up on the sales counter of the Bonnin and Morris warehouse. Examples of their soft-paste wares have been found in similar contexts in the Old City area of Philadelphia. Many of those objects have significant firing flaws and surely were considered “seconds” (figs. 12, 13). Of course the selling of seconds has always been part of the pottery business. In a 1768 letter, English porcelain manufacturer William Cookworthy wrote that even the failed “Product of this kiln together with that of our former Experiments, hath been sold for upwards of Twenty two Pounds!”[60] Such was the demand for even imperfect specimens of his newly founded porcelain works in Plymouth. In another letter discussing the status of Cookworthy’s porcelain, John Mudge noted: “Mr Cookworthy has inform’d you that some of the imperfect ware has sold for upwards of £20 & there now is a larger quantity of the same kind in stock.”[61] These letters suggest that the selling of experimental and imperfect objects was standard practice for these fledgling porcelain enterprises.

Andrew Duché’s role in the Bonnin and Morris enterprise has always been a subject of speculation. Researchers have noted that the timing of his move to Philadelphia would have placed him in a position of knowledge of, if not active participation in, the venture. Just how close was Duché to the Bonnin and Morris operation? According to their newspaper advertisements, Bonnin and Morris operated, in addition to their factory in the Southwark section of Philadelphia, a “Ware-House, the east side Second-street, a few doors below Market Street.”[62] The inclusion of “below Market Street” puts its location on the south side. When Duché moved to Philadelphia in 1769, he acquired for £130 the rights to receive £9 Pennsylvania currency rent for a lot, 14 feet by 30 feet, on High Street and Strawberry Alley. As figure 14 illustrates, these two locations are less than 100 yards from each other. It is inconceivable that the leading porcelain potters in America were so close and did not communicate or collaborate.

Other tangential evidence of the Duché connection to the products of Bonnin and Morris relates to their molded rococo-style sauceboats. As previously mentioned, British potter William Cookworthy purportedly met with Andrew Duché in 1745. Cookworthy went on to find a domestic source for kaolin and china stone in Cornwall. Many of the designs made by Bonnin and Morris, although similar to Bow porcelain prototypes, appear to have elements unique to their factory. Yet one of their molded sauceboats, now in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum (fig. 15), appears to be an exact copy of a Plymouth example (fig. 16).[63] In his 1980 article on Bonnin and Morris, Michael K. Brown addressed this similarity and speculated that the Plymouth mold may have found its way to Philadelphia via an “an émigré craftsman—perhaps one who was leaving England in 1770 when Cookworthy moved his manufactory from Plymouth to Bristol, which was also about the same time that Bonnin and Morris were recruiting workmen to come to America.”[64] A more tantalizing explanation is that these sauceboats were given to Duché personally by Cookworthy for his use in America and were subsequently incorporated into the American China Manufactory’s repertoire.

Mention must be made of another possible candidate for the maker of the hard-paste porcelain bowl. A mysterious “young German, completely skilled in the process of making porcelain” appears in a May 1773 advertisement of the pending auction of the china works.[65] The possible identity of this individual has been discussed by both Graham Hood and Diana Stradling without much success.[66] He was touted as “someone [who] would readily undertake the management, upon reasonable terms, either in partnership or otherwise” as part of the sale agreement, but the property was sold without further mention of him. While it is notable that the Meissen porcelain works in Germany is the site of the first successful European hard-paste porcelain effort, there is nothing more to suggest a connection between the bowl and this unknown man. If indeed he was “completely skilled in the process of making porcelain in the German hard-paste tradition,” those abilities are not reflected in the poorly finished, undecorated, and underfired bowl illustrated in figures 8 and 11.

Conclusion

We believe that the newly discovered hard-paste porcelain bowl is an artifact from a short period of experimentation conducted at the American China Manufactory. It most likely was made during the trials announced in August 3, 1772. At the very least, the bowl carries elements of Andrew Duché’s invisible hand, given his role in the discovery of the Cherokee clay and his experiments with porcelain manufacture both in his Savannah potteries and in one or more English porcelain works. Duché’s physical and intellectual proximity to the Philadelphia porcelain works suggests he was directly involved with the creation of the bowl within the Bonnin and Morris factory setting.

Future research may corroborate Duché’s role in Philadelphia’s porcelain incubator. For now, we are confident that the bowl is the first physical proof of an American effort to produce hard-paste porcelain in the eighteenth century.[67] Its existence gives more confidence to the belief that Duché did succeed in making true porcelain much earlier, during his time in Savannah in the 1740s. And there is the outside chance that the bowl may be a relic from those earlier experiments and traveled with Duché when he relocated to his hometown. Certainly, scholars and archaeologists should pay closer attention to potential finds in or near his Savannah properties where he operated his kilns. Although the Earl of Egmont’s 1739 boast of Duché’s ability was pure exaggeration and historically inaccurate, perhaps Duché can truly claim the title as the first man in America to find the “true material and manner of making porcelain.”

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

First and foremost we thank the Museum of the American Revolution for permitting this study. Scott Stephenson, vice president of collections, exhibitions, and programming; Neal Hurst, assistant curator; and Michelle Presnall, collections manager and registrar, were instrumental in allowing access to the finds recovered from the excavations and facilitating the study and analysis of this bowl. Staff members from Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc., in particular Rebecca Yamin and Tod Benedict, were instrumental in the interpretation of Feature 16, and Sarah Ruch provided invaluable help with report photographs and graphics. The Chipstone Foundation is acknowledged for its support of the analysis and conservation of the bowl. Jon Prown and Luke Beckerdite are thanked for their enthusiastic understanding of the importance of this find. Michelle Erickson, drawing on her experience with Bonnin and Morris porcelain, was immensely helpful with her comments on the production aspects the bowl. Scott Nolley of Fine Art Conservation of Virginia contributed his expertise and encouragement in the conservation and mending of the bowl. Debbie Miller provided much-needed assistance with historical information from Philadelphia, and we are grateful for her stewardship of the larger Philadelphia archaeological resource. Ron Fuchs, curator of the Reeves Collection at Washington and Lee University, kindly commented on an earlier version of the manuscript. Heartfelt thanks to Graham Hood, who made the time to examine the bowl and has long encouraged and inspired the pursuit of the story of early American porcelain. Without the analysis and expertise of geologist Victor Owen, this article would not have been possible. Victor’s enthusiastic pursuit of the secrets of eighteenth-century Anglo-American porcelain is unsurpassed. He would have a lot to talk about with Andrew Duché.

Rose Kerr and Nigel Wood suggest that porcelain was being developed at the end of the sixth or the beginning of the seventh century in northern China. See Kerr and Wood, Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 12, Ceramic Technology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), p. 143.

Janet Gleeson, The Arcanum: The Extraordinary True Story (New York: Grand Central Publishing, 1998); Edmund De Waal, The White Road: Journey into an Obsession, 1st American ed. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015).

Julie Emerson, Jennifer Chen, Mimi Gardner Gates, Porcelain Stories: From China to Europe (Seattle: Seattle Art Museum in association with University of Washington Press, 2000).

J. Victor Owen, “A New Classification Scheme for Eighteenth-Century American and British Soft-Paste Porcelains,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 120–40.

As this article was nearing completion, a new publication was released that chronicles the British search for the secrets of hard-paste porcelain. See Brian Adams, True Porcelain Pioneers: The Cookworthy Chimera, 1670–1782 (Devon, U.K.: Printed for the author, 2016).

Stanley South, “John Bartlam’s Porcelain at Cain Hoy, 1765–1770,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 196–203; Lisa R. Hudgins, “John Bartlam’s Porcelain at Cain Hoy: A Closer Look,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 203–8.

Robert Hunter and Alexandra A. Kirtley, “Recent Scholarship on the American China Manufactory of Bonnin and Morris,” Antiques 173, no. 2 (January 2008): 66–71.

Graham Hood, Bonnin and Morris of Philadelphia: The First American Porcelain Factory, 1770–1772 (Chapel Hill: Published for the Institute of Early American History and Culture at Williamsburg, Va., by the University of North Carolina Press, 1972), a book reprinted in its entirety in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 2–75. See also Michael K. Brown, “Piecing Together the Past: Recent Research on the American China Manufactory, 1769–1772,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 133, no. 4 (1989): 557–59, reprinted in the 2007 issue of Ceramics in America; Robert L. Giannini III, “Ceramics and Glass from Home and Abroad,” in John C. Milley, Treasures of Independence: Independence National Historical Park and Its Collections (New York: Mayflower Books, 1980); Robert Hunter, “John Bartlam: America’s First Porcelain Manufacturer,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2007), pp. 193–96; Diana Stradling, “Bonnin & Morris: Reading between the Lines,” Transactions of the English Ceramic Circle 20, pt. 3 (2009): 613–31; and Diana Stradling, “Bonnin and Morris: Reading between the Lines,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2013), pp. 179–99.

Graham Hood, “The Career of Andrew Duché,” Art Quarterly 31 (1968): 168–84. Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “Andrew Duche: A Potter ‘a Little Too Much Addicted to Politicks,’” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 17, no. 1 (May 1991): 1–101.

Rebecca Yamin, Principal Investigator, with contributions by Tod L. Benedict, Meagan Ratini, Kevin C. Bradley, Leslie E. Raymer, Juliette Gerhardt, Kathryn Wood, Timothy Mancl, and Claudia L. Milne, Archaeology of the City—The Museum of the American Revolution Site Archaeological Data Recovery, Third and Chestnut Streets, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2 vols. (West Chester, Pa.: Commonwealth Heritage Group, 2016), vol. 1.

See J. Victor Owen, Joe Petrus, and Xiang Yang, “The Geochemistry of a True Porcelain Punch Bowl Excavated in Philadelphia,” in this volume.

Robert L. Giannini III, “Anthony Duche Sr., Potter and Merchant of Philadelphia,” Antiques 119 (January 1981): 198–203.

The earliest comprehensive treatment of Duché is found in a series of articles by G.A.R. Goyle [Rudolph P. Hommel], “First Porcelain Making in America,” Chronicle of the Association of Early American Industries 1 (1934–35): 8–11; Rauschenberg, “Andrew Duche: A Potter.”

South Carolina Gazette, April 5, 1735.

. Jean-Baptiste du Halde, The General History of China, translated by R. Brookes (London: J. Watts, 1736).

Rauschenberg, “Andrew Duche: A Potter,” p. 20.

Allen Candler, ed., The Colonial Records of Georgia, 26 vols. (Atlanta, Ga.: Franklin Printing and Publishing Co., 1904), 22:168–69.

Earthenware and stoneware fragments attributed to Andrew Duché’s Savannah pottery have been excavated in the colonial settlement of Frederica, Georgia, and were reported on in Nicholas Honercamp, “The Material Culture of Fort Frederica—The Thomas Hird Lot” (master’s thesis, University of Florida, 1975), pp. 40–42; and Nicholas Honerkamp, “Frontier Process in Eighteenth Century Colonial Georgia: An Archaeological Approach” (Ph.D. diss., University of Florida, 1980), pp. 45–50.

. Candler, ed., Colonial Records of Georgia, 22:168–69.

Ibid.

Ibid., 5:141–42.

Ibid., 4 (supp.): 46; Rauschenberg, “Andrew Duche: A Potter.”

Candler, ed., Colonial Records of Georgia, 5:657. E. Merton Coulter, ed., The Journal of William Stephens, 1741–1743 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1958), pp. 140–42.

Candler, ed., Colonial Records of Georgia, 2:289, 5:196–97, 5:657.

Llewellynn Jewitt, The Ceramic Art of Great Britain (London, 1883), pp. 84–85.

W. R. H. Ramsay, Anton Gabszewicz, and E. G. Ramsay, “‘Unaker’ or Cherokee Clay and Its Relationship to the ‘Bow’ Porcelain Manufactory,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 17, pt. 3 (2001): 473–99.

William R. H. Ramsay, Frank A. Davenport, and Elizabeth G. Ramsay, “The 1744 Ceramic Patent of Heylyn and Frye: ‘unworkable unaker formula’ or Landmark Document in the History of English Ceramics?,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 118 (1): 11–34.

J. V. G. Mallet, “The ‘A’ Marked Porcelains Revisited,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 15 (1994): 240–57. Recent scientific analysis by W. Ross Ramsay, Judith A. Hansen, and E. Gael Ramsay has suggested that this group was made using the Cherokee unaker. They strongly believe that historical and scientific evidence shows that it was Andrew Duché who brought the clay and the results of his Savannah experimentation to the proprietors of the Bow manufactory.

Hugh Owen, Two Centuries of Ceramic Art in Bristol (London, 1873), pp. 7–8.

F. Severne Mackenna, Cookworthy’s Plymouth and Bristol Porcelain (Leigh-on-Sea, Eng.: F. Lewis Publishers, 1946), pp. 26–27.

Adams, True Porcelain Pioneers, pp. 101–38.

A. S. Salley, ed., Journal of the Commons House of Assembly of S.C. 19 Jan. 1748–29 June 1748 (Columbia, S.C., 1947), p. 171.

Bradford L. Rauschenberg, “‘A Clay White as Lime . . . of Which There is a Design Formed by some Gentlemen to Make China’: The American and English Search for Cherokee Clay in South Carolina, 1745–75,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 17, no. 2 (November 1991): 67–79.

Mabel L. Webber, ed., “Journal of Robert Pringle, 1746–1747,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 26 (1925): 102.

David Ramsay, The History of South Carolina, from Its First Settlement in 1670 to the Year 1808, 2 vols. (Newberry, S.C.: W. J. Duffie, 1809), 2:470.

Philip M. Hamer and George C. Rogers Jr., eds., The Papers of Henry Laurens (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1970), 2:431.

Edmund Berkeley and Dorothy Smith Berkeley, Dr. Alexander Garden of Charles Town (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1969), pp. 93–94.

Ibid., p. 486.

Hugh Owen, Two Centuries of Ceramic Art in Bristol, Being a History of the Manufacture of “The True Porcelain” by Richard Champion (London, 1873), p. 8; J.V.G. Mallet, “Cookworthy’s First Bristol Factory of 1765,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions, pt. 2 (1974): 212–20.

William L. Anderson, “Cherokee Clay, from Duché to Wedgwood: The Journal of Thomas Griffiths, 1767–1768,” North Carolina Historical Review 63, no. 4 (October 1986): 477–510.

Robin Reilly, Josiah Wedgwood 1730–1795 (London: Macmillan London, 1992), pp. 159–60.

For a fuller discussion of Duché’s time in England and his residence in Bath, see Rauschenberg, “Andrew Duche: A Potter,” pp. 76–77.

Mackenna, Cookworthy’s Plymouth and Bristol Porcelain.

In his assessment of Andrew Duché, Brian Adams concludes that he was indeed successful in producing an American true porcelain in the 1740s. Adams, True Porcelain Pioneers, p. 24.

Graham Hood tries to connect this with Duché, “who was in Philadelphia about this time, has been named as an entrepreneur previously shipping clays from South Carolina to London for the use of the Bow factory” but acknowledges that “there is no known connection between him and Bonnin and Morris.” Hood, “The Career of Andrew Duché,” p. 180. Brad Rauschenberg tries harder to not dismiss it as coincidence. He writes, “It is perhaps ironic that Duche returned to the city of his birth in time to witness the success of the first documented American porcelain factory. Although proof of any association between Duche and the Bonnin and Morris manufactory has not been found, it might not be illogical to suppose that there was a connection, at least through proximity.” He allows that “it is therefore possible that Duché contributed to the factory.” Rauschenberg, “Andrew Duche: A Potter,” pp. 77–78.

George C. Rogers Jr. and David R. Chestnutt, eds., The Papers of Henry Laurens (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1980), 8:55.

Alfred Coxe Prime, comp., The Arts & Crafts in Philadelphia, Maryland and South Carolina, Gleanings from Newspapers, 2 vols. ([Topsfield, Mass.]: Walpole Society, 1929–32), vol. 1, 1721–1785 (1929), p. 120.

John L. Cotter, Daniel G. Roberts, and Michael Parrington, The Buried Past: An Archaeological History of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993).

Philadelphia County Recorder of Deeds 1789, pp. 182–84.

“Archeology of the City—The Museum of the American Revolution Site Archeological Data Recovery,” pp. 69–80.

Fine Art Conservation of Virginia, available online at http://www.facva.com.

J. Victor Owen, “Geochemical Distinctions between Bonnin and Morris Porcelain (Philadelphia, 1770–72) and Some Contemporary Phosphatic British Wares,” Geoarchaeology 16 (2001): 785–802.

J Victor Owen, “‘Too little, too late’: The Geochemistry of a 1773 Philadelphia Porcelain Openwork Basket,” Journal of Archaeological Science 36, no. 2 (January 2009): 333–42; Hunter and Kirtley, “Recent Scholarship on the American China Manufactory”; Nicholas Pane, “Mr Ball the English Potter and the American China Manufactory,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 20, pt. 3 (2009): 633–45.

Candler, ed., Colonial Records of Georgia, 4 (supp.), pp. 220–21.

Ibid.

Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, American Porcelain, 1770–1920 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989), p. 11.

Ibid.

Owen, Petrus, and Yang, “The Geochemistry of a True Porcelain Punch Bowl Excavated in Philadelphia,” in this volume.

Stradling, “Bonnin and Morris: Reading between the Lines,” p. 192.

Cornwall Record Office reference DDF(4) 80/21, as cited in Adams, True Porcelain Pioneers, p. 411.

Cornwall Record Office reference DDF(4) 80/23, as cited in ibid., p. 413.

Pennsylvania Journal, September 5, 1771, and Pennsylvania Gazette, January 13, 1772.

Nicolas Panes, British Porcelain Sauceboats of the 18th Century (Wales: Gomer Press, 2009). Two recently recorded archaeological examples also appear to represent copies of the Cookworthy sauceboat design and are illustrated in J. Victor Owen, John D. Greenough, and Nick Panes, “Statistical Evaluation of Analytical Data for Eighteenth-Century American and British Sulphurous Phosphatic Porcelains,” in this volume.

Brown, “Piecing Together the Past” (Ceramics in America), p. 86.

Pennsylvania Chronicle, May 24–31, 1773. Hood, Bonnin and Morris of Philadelphia (reprint in Ceramics in America), p. 16.

Stradling, “Bonnin and Morris: Reading between the Lines,” pp. 191–92.

A Chinese-shaped porcelain punch bowl with underglaze blue decoration, postulated as being of Duché manufacture in Savannah, was illustrated and discussed in Ruth Monroe Gilmer, “Andrew Duché and His China, 1738–1743,” Apollo 45 (1947): 128–30. This claim was challenged by Arthur W. Clement in a subsequent article, but still defended by Ruth Monroe Gilmer in “Andrew Duché—America’s First China Maker, born circa 1709,” Apollo 48 (1948): 63–65. A color image of this bowl is reprinted in Adams, True Porcelain Pioneers, p. 22. The whereabouts of this bowl are not known.