Jug sherds, Liverpool, ca. 1785–1790. Creamware. (Photos, courtesy Coastal Environments, Inc.) The transfer print commemorates the Revolutionary War with the “Success to the United States of America” pattern.

Fragments of hand-painted polychrome vessels found at the Dortch site, Staffordshire, ca. 1795–1799. Pearlware.

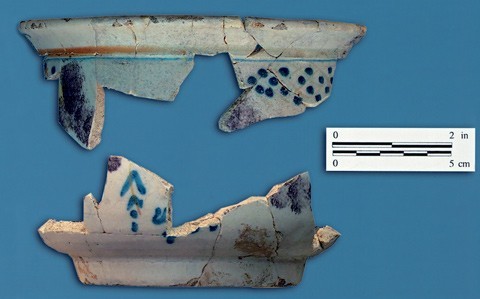

Hand-painted blue teawares, Staffordshire, ca. 1780–1799. Pearlware. Scale is in inches and centimeters

Transfer-printed blue wares from the Dortch site, Staffordshire, ca. 1790–1799. Pearlware. The sherd at the upper left was fashioned into a gaming piece.

Flower bowl, England, eighteenth century. Tin-glazed earthenware. Examples of English delft are rarely found on Louisiana sites. Scale is in inches and centimeters.

The John Dortch archaeological site is located near St. Francisville, West Feliciana Parish, Louisiana. Occupied between 1794 and 1799, the site, then part of Spanish West Florida, is one of only a few Spanish-colonial period settlements in the area. Dortch, a Revolutionary War veteran from South Carolina, settled his family here while Spain was still in control of the region. While most contemporary sites in South Louisiana yield French ceramics despite being under Spanish rule, excavation of the Dortch site produced numerous English wares and very few French ceramics.

Approximately 5 percent of the artifacts recovered from the site are historic ceramics. These consist mostly of creamware and pearlware in a variety of decorations. Other English wares within the assemblage include black-glazed redware, delft, basalt, and unglazed red stoneware.

A mere seventy sherds of creamware are decorated, yet the variety of decoration is remarkable. The decorations employed include overglaze transfer-printed sherds in red as well as black; overglaze hand-painted sherds in red; and molded sherds. Several of the black transfer-printed sherds were reconstructed into a portion of a Liverpool jug commemorating the Revolutionary War (fig. 1). The pattern, “Success to the United States of America,” is considered rare in antique collections.[1] The molded sherds represent portions of a breadbasket and a candlestick.

Over half of the pearlwares are decorated and mostly represent teawares. The majority of these are polychrome hand-painted wares (fig. 2), whereas others exhibit molding, fluting, or annular banding. The remaining hand-painted pearlware vessels have blue Chinese motifs, in imitation of Chinese porcelain. One such motif occurs on a cup, a plate, and a saucer (fig. 3).

Blue and green edgewares represent the second most popular pearlware decoration recovered. A few pearlware sherds are also transfer-printed in blue, with Chinese motifs. One has even been fashioned into a gaming piece (fig. 4).

A small percentage of the ceramics recovered are tin-enameled wares, primarily identified as delft. Most of the delft sherds represent a large portion of a flower bowl form (fig. 5)—one of the most remarkable finds from the Dortch site, with its powder purple and polychrome hand-painted decoration. Although delft is common at English-colonial archaeological sites, very few sherds of delft have ever been recovered from Louisiana archaeological sites, and even fewer have been decorated.[2]

Dortch apparently brought a number of English ceramics from South Carolina when he moved to Spanish West Florida circa 1793. The variety, quantity, and quality of English ceramics indicate that he was a man of means. The assemblage’s well worn and highly fragmented condition suggests that the Dortch home served as an inn or meeting hall along a remote frontier road for wealthy businessmen, politicians, traders, and possibly even local revolutionaries.

Sara A. Hahn

Archaeologist

Coastal Environments, Inc.

<shahn@coastalenv.com>

David Arman and Linda Arman, Anglo-American Ceramics Part 1, Transfer Printed Creamware and Pearlware for the American Market 1760–1860 (Portsmouth, R.I.: Oakland Press, 1998), p. 181.

Jill-Karen Yakubik, “Ceramic Use in Late-Eighteenth-Century and Early-Nineteenth-Century Southeastern Louisiana” (Ph.D. diss., Tulane University, New Orleans, 1990), pp. 289–91; Jeffrey P. Brain, Tunica Treasure (Cambridge, Mass.: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University; Salem, Mass.: Peabody Museum of Salem, 1979), p. 44.