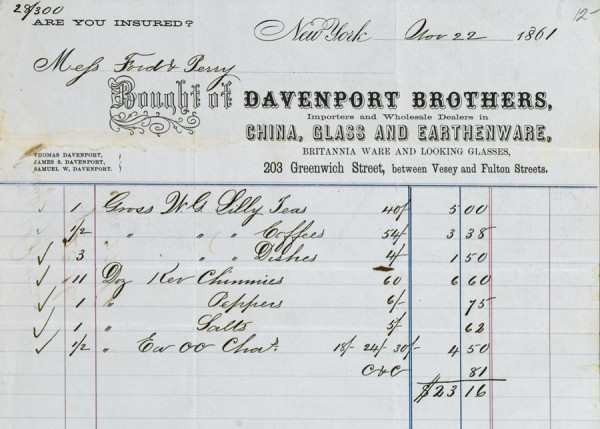

Invoice, Davenport Brothers, New York, 1861. (Authors’ collection; all photos, Gavin Ashworth.)

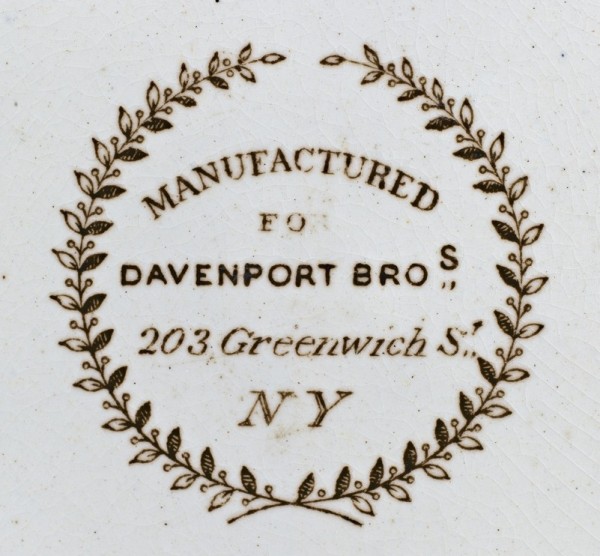

Plate, England, 1855–1860. Ironstone. D. 8 3/4". Brown printed importer’s mark: “MANUFACTURED / FOR / DAVENPORT BROs../ 203 Greenwich St../ N Y.” Unfortunately, the plate does not bear a potter’s mark or pattern name.

Detail of the mark on the underside of the plate illustrated in fig. 2.

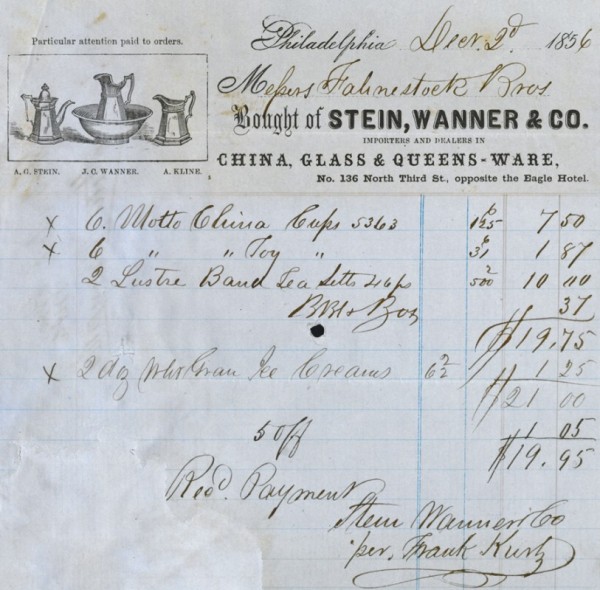

Invoice, Stein, Wanner & Co., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1856. The invoice bears a vignette with a white granite pitcher and lists wares sold to Fahnestock Brothers in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

Pitcher, William Adams and Son, Tunstall, Staffordshire, 1850–1860. White granite. H. at handle 10". Mark: printed on underside, American eagle and “SUPERIOR WHITE GRANITE.” This pitcher is very close in form to the one in the center of the vignette on the invoice illustrated in fig. 4.

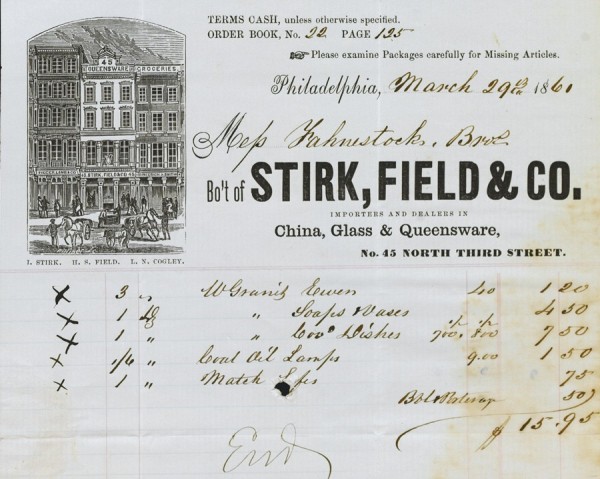

Invoice, Stirk, Field & Co., Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, March 29, 1861. The vignette shows the facade of the company’s building with a sign for “QUEENSWARE” and, on the street below, a typical Staffordshire crate being unpacked. The invoice is for a list of wares sold to Fahnestock Brothers.

Muffin plate, Joseph Clementson, Shelton and Hanley, Staffordshire, ca. 1839–1855. Whiteware. D. 5". Mark: on underside, printed in brown, “S. FAHNESTOCK / IMPORTER.” Samuel Fahnestock founded the firm that became Fahnestock Brothers in 1855. The plate decoration is the Lucerne pattern.

Detail of the importer’s mark on the underside of the muffin plate illustrated in fig. 7.

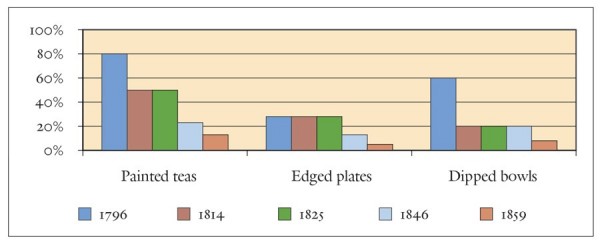

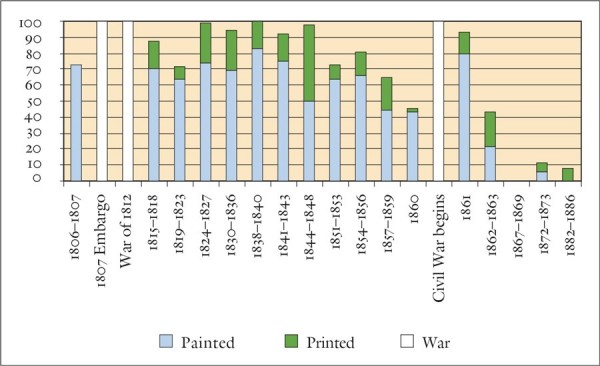

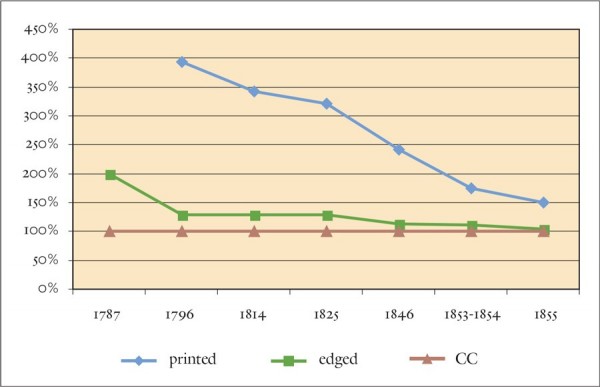

Cost of painted teas, edged plates, and dipped bowls as a percentage above the cost of CC ware, 1796–1859: painted teas, edged plates, dipped bowls.

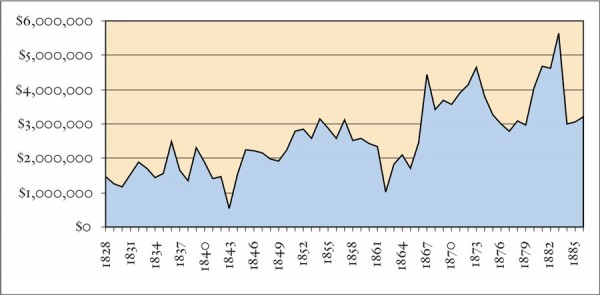

Value of imported English ceramics, 1828–1886. Source: U.S. Treasury Reports

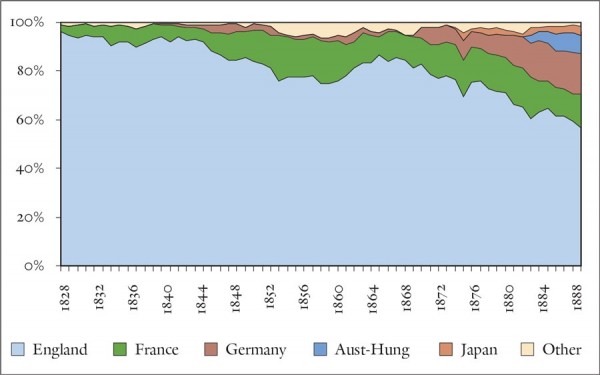

Market share of imported ceramics, 1828–1888. Source: U.S. Treasury Reports

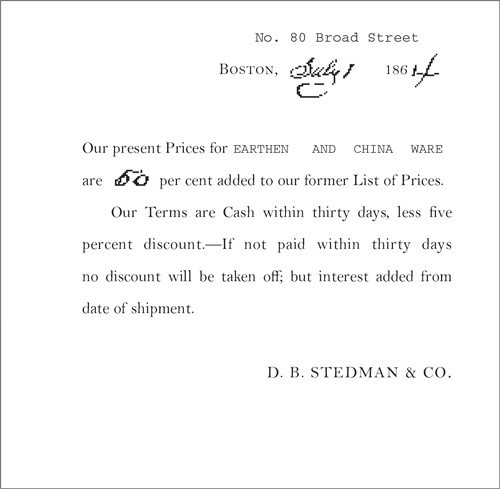

Transcription of a notice dated July 1, 1864, in which D. B. Stedman & Co., Boston, Massachusetts, announced a 50 percent price increase. The original is in the Warshaw Collection of Business Americana-Pottery, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

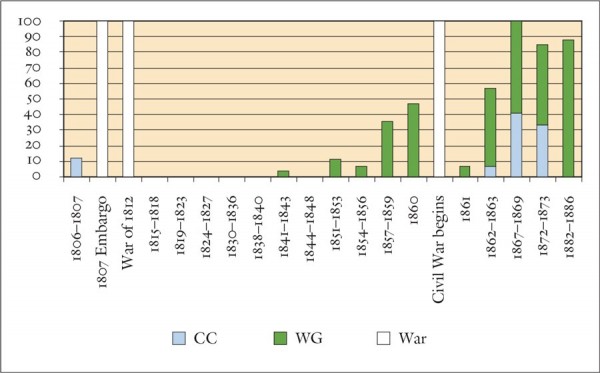

Percentage of undecorated teas (CC and White Granite wares) listed in the invoice sample.

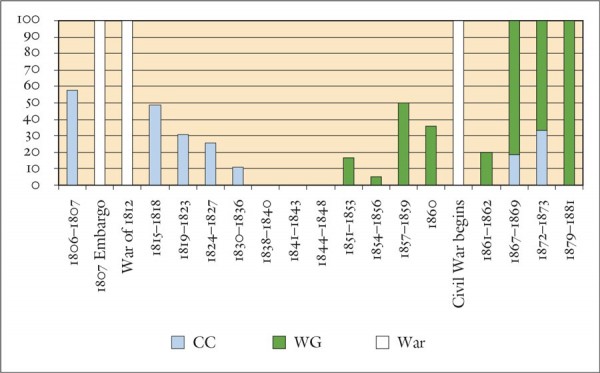

Percentage of undecorated plates (CC and White Granite wares) listed in the invoice sample.

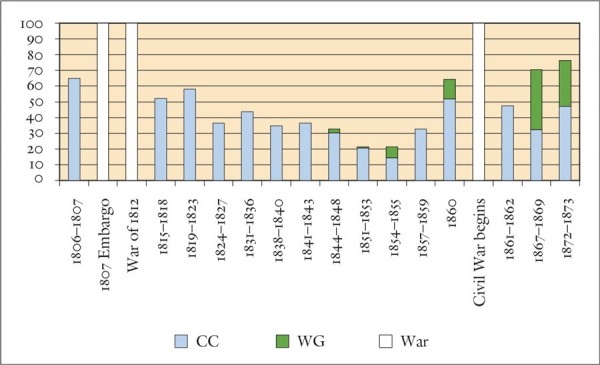

Percentage of undecorated bowls (CC and White Granite wares) listed in the invoice sample.

Percentage of decorated teas (Painted and Printed) listed in the invoice sample.

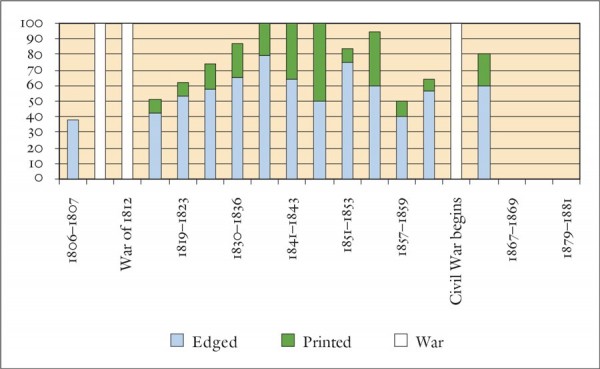

Percentage of decorated plates (Edged and Printed) listed in the invoice sample.

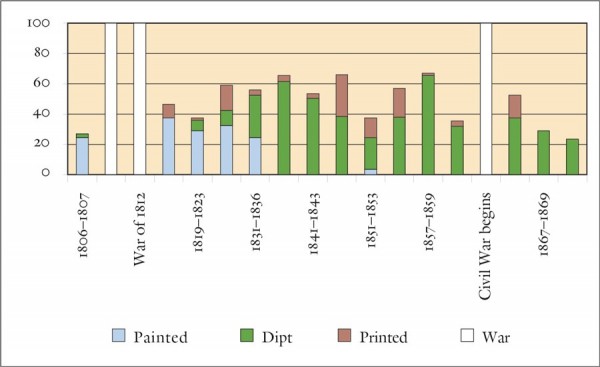

Percentage of decorated bowls (Painted, Dipped, and Printed) listed in the invoice sample.

Bowls, Don Carpentier, East Nassau, New York, ca. 1995. Earthenware. D. of bowl at right 6 1/2". The three bowls shown are reproductions of dipped ware: variegated, fan, and mocha.

Bowls, Staffordshire, ca. 1830–1850 (left), ca. 1850–1880 (right). Whiteware. D. of bowl at left 4 1/2", H. 2 3/4". The bowl at left was turned, the one at right was jiggered.

Saucer, England, ca. 1780–1800. China glaze. D. 4 7/8".

Saucer, Ralph and James Clews, Staffordshire, ca. 1818–1834. Pearlware. D. 6".

Saucer, Staffordshire, ca. 1810–1820. Pearlware. D. 5 1/8". The painted decoration on the border is a classical husk pattern.

Saucer, Staffordshire, ca. 1830– 1835. Whiteware. D. 5 7/8". This example has a thick border of strawberries painted in chrome colors, a more complex design than found in many patterns of the period.

Saucer, Staffordshire, ca. 1845– 1860. D. 5 3/4". The very small sprigs decorating this saucer are painted in chrome colors. On one side the rim has a thicker glaze with a light blue tint—clearly meant to make a whiter ware rather than to imitate Chinese porcelain.

Saucer, England, ca. 1845–1880. Whiteware. D. 5 3/4". The decoration on this saucer was achieved using four different cut sponges, with the exception of the black stem of the plant, which was painted by hand.

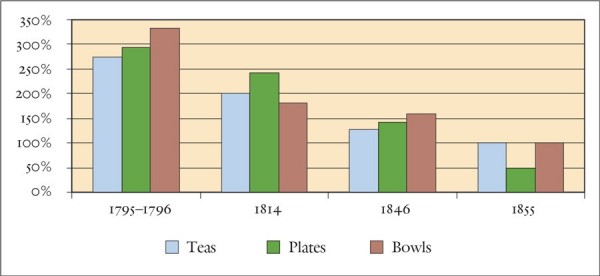

Percentage above the cost of CC ware for printed teas, plates, and bowls.

The changing cost relationship between CC, shell-edged, and printed plates.

Average discounts on 122 Staffordshire invoices for ceramics exported to America.

Plate, John Turner, Lane End, Staffordshire, ca. 1790–1806. China glaze. D. 7 3/4". Turner went bankrupt in 1806.

Plate, probably J. and R. Riley, Burslem, 1814–1828. Pearlware. D. 9 7/8".

Plate, Staffordshire, ca. 1818–1830. Pearlware. D. 10 1/8". The plate has a rim blemish, which would have made it a “second” in quality.

Plate, S. & S., ca. 1845–1860. Ironstone. D. 10 1/2". Marks: impressed on underside, “KERR’S / OLD CHINA HALL / PHILA.”; printed in blue on underside, “ONTARIO / S & S” within decorative border. “Ontario” refers to the pattern.

Detail of the mark on the underside of the plate illustrated in fig. 33.

Plate, Livesley Powell & Co., Hanley, Staffordshire, 1851–1866. Whiteware. D. 9". The Rose and Bell sheet pattern is printed in purple with red and blue painted highlights.

Plate, Staffordshire, ca. 1860–1870. Ironstone. D. 9 1/2". Marks: None. The plate’s border is decorated with floral sprays, and the center shows a group of floral sprays with a flag, plus a liberty cap vignette that was commonly used during the Civil War.

For far too long, ceramic scholarship has focused primarily on the potters who produced the wares and on ceramic technology, chronology, and connoisseurship. Changes in ceramic ware types and styles have been described as a by-product of the fashion system, the results of social emulation, and changes brought about by consumer demand. Was the industrial revolution being driven by a consumer revolution? Evidence from the nineteenth century suggests that oversupply and falling prices drove changing consumption patterns, yet little documentation and analysis of quantified data have been presented. This paper attempts to address that problem. We have extracted and quantified the purchases of teas (cups and saucers), plates, and bowls from 101 invoices dating between 1806 and 1886 that list the ceramics sold by New York importers and wholesalers to the “country trade,” composed of the owners of country stores in small villages outside the urban areas. New perspectives on the forces affecting consumption patterns emerge when this information is put into the contexts of wars, embargoes, deflation, and inflation. In the words of Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign, “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Synopsis of Research on English Ceramics

Staffordshire historians and potters recorded some of the earliest documentation of the English ceramics industry. Based on interviews in 1776 with aging potters, Josiah Wedgwood compiled a list of potters operating in Staffordshire between 1710 and 1715.[1] Simeon Shaw’s History of the Staffordshire Potteries (1829) also relies extensively on the memories of potters and workers for information regarding when and by whom innovation occurred.[2] Enoch Wood collected early wares produced by the Staffordshire potters as well as documents related to the potteries. This collection was kept in his factory as a visual memory of the past. He was also known for putting caches of Staffordshire pottery in the cornerstones of buildings erected in the Potteries.[3]

The serendipitous survival of a massive assemblage of Josiah Wedgwood’s papers, which in the 1840s were being sold as scrap paper, is perhaps what sparked interest in collecting his wares. Joseph Mayer, whose relatives were Staffordshire potters, came across these papers when he ducked into a scrap store to get out of a rainstorm. When he asked the proprietor what the papers were being used for, he was told that butchers and shopkeepers used them to wrap cheese and bacon. Mayer purchased all of the remaining papers and, after organizing them, turned them over to Eliza Meteyard, who used them as the basis for her two-volume biography of Josiah Wedgwood, which was published in 1865, the same year Llewellyn Jewitt published his Life of Josiah Wedgwood.[4] Information provided by Meteyard and Jewitt is the foundation of much of our ceramic knowledge, providing a road map for collecting English ceramics that spurred interest in the subject. Following these early publications, collectors and antiquarians generated a flood of books on English ceramics that has not yet crested.

Books by collectors typically present a connoisseur’s perspective, illustrating examples with specific data such as potters’ marks or dated inscriptions but often neglecting the more commonplace and undecorated wares. Research is focused primarily on which factory produced an object and when—introduction dates for wares, types of decoration, and patterns—which is useful information but fails to establish when wares stopped being produced. Terms such as rare, popular, and common are used without defining their relative meaning, and all too often collector literature does not put the ceramics into context with other types of material culture.

New approaches to ceramics research by social historians, museum curators, and historical archaeologists began to develop in the 1930s. “Room displays,” begun in the Colonial Revival period, re-created the past by decorating rooms with the types of objects that would have been used together. Restorations such as Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, Plimouth Plantation in Massachusetts, and Henry Ford’s Greenfield Village in Michigan began to rigorously research documents such as probate inventories in an effort to identify the objects that functioned together. Probate inventories were also used to study ceramic ownership patterns.[5] The master’s degree program in American material culture offered by the Winterthur Program, which was established in 1952 by the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum and the University of Delaware, has fostered greatly expanded interpretations involving ceramics. Rodris Roth’s 1961 study, Tea Drinking in Eighteenth-Century America: Its Etiquette and Equipage, which places tea services within a broader social context, is an excellent example of this type of research.[6]

In 1972 Dwight Lanmon organized a conference at the Winterthur Museum that focused on the state of ceramic research by historical archaeologists, social historians, and curators. The papers, published in a volume titled Ceramics in America, served as a very useful summary of the state of ceramics research, although little use was made of commercial records, such as account books, price lists, and invoices.[7] Changes in direction were beginning to take place among English economic and social historians, however. Notable was a series of articles by Neil McKendrick, who used information from the Wedgwood papers to show how Wedgwood and Bentley marketed their wares through social emulation. This was done by selling the new products to the upper social classes to help create a demand for them by those of lower social position. From the study of the marketing done by Wedgwood and Bentley and other English entrepreneurs, McKendrick and others have argued that the Industrial Revolution was driven by demand for new products rather than by supply because production costs decreased.[8]

Much of the primary data used in this paper was accumulated by George Miller while on a series of fellowships and grants. In 1979 he was awarded an NEH Fellowship to Winterthur Museum and Library to study the 1817–1831 account book of George M. Coates, a Philadelphia earthenware dealer, which led to a conference at Winterthur titled “Marketing Ceramics in North America.”[9] Four of the conference papers were based on account books and invoices from importers, jobbers, and potters and suggested new areas for investigation.[10]

In 1980 Miller published a set of ceramic index values based on the price of undecorated creamware from the 1780s to the 1860s.[11] The price information from which the index values were generated was taken from the Staffordshire printed price-fixing lists—agreements among the potters setting the minimum price for their wares and the rates of discount for such things as breakage and ready cash—and from potters’ invoices for wares shipped to America.

A 1986 NEH grant titled “English Ceramics in America, 1760 to 1860: Marketing, Prices, and Availability” provided funding for George L. Miller, Ann Smart Martin, and Nancy S. Dickinson to do further research on ceramic prices and marketing.[12] A summary of that research is in the paper “Changing Consumption Patterns: English Ceramics and the American Market from 1770 to 1840.”[13] Another article from that research was “A Revised Set of CC Index Values for Classification and Economic Scaling of English Ceramics from 1787 to 1880.”[14]

In his 1997 monograph “‘Supplying the Present Wants of Our Yankee Cousins...’: Staffordshire Ceramics and the American Market, 1775–1880,” Neil Ewins presents 208 Staffordshire potters’ invoices for wares sent to America, along with a summary of the wares enumerated and the total value for each of the types listed.[15] At first glance it seemed that Ewins had provided a baseline from whence to start compiling data on the popularity of the various wares. Unfortunately, there are problems with these data in terms of time coverage and the mix of ceramics they contain. As can be seen in Table 1, 75 percent of the invoices are from the 1830s and the 1870s. This limitation is exacerbated by the fact that, as shown in Table 2, the overwhelming majority of the invoices—more than 80 percent—were for orders from Philadelphia. Throughout the nineteenth century New York was the major port for imported wares, yet it accounts for only about 14 percent of the invoices used in Ewins’s monograph. One must wonder why such a high percentage of these invoices went to Philadelphia and so few to other cities.

Moreover, the potters’ invoices are not often representative of the mix of ceramics being purchased by American consumers. While invoices for wares ordered by American importers represent what they felt were in demand and what would sell in their markets, during times of economic distress many potters with surplus inventories exported their wares to the American market at their own risk. These wares, commonly shipped to commission agents, often wound up at auctions where they sold below cost. Auctions—on a wide variety of goods, not just ceramics—often oversupplied the market and kept profit margins low, which led to anti-auction movements.[16] The main thing to keep in mind for wares shipped at the potters’ risk is that, instead of market demand, they represent inventory that the potter needed to unload to secure funds.[17] Wares listed in invoices sent at the potter’s risk to commission merchants are generally not a good reflection of the mix of ceramics being sold by importers and jobbers. For example, in some of the invoices abstracted by Ewins, 100 percent of the wares were printed wares and unrepresentative of the mix of wares being sold by country merchants.

Invoices for Ceramics to the Country Trade

Archaeologists have long been stuck in the rut of studying individual household consumption patterns of English ceramics in the American market, and it is time to expand that view to include the range of wares being purchased at a community level. Because this information cannot be adequately gleaned from surviving potters’ invoices, it is clear that another approach is needed to document those patterns. This brings us to the subject of this paper, which focuses on the ceramics sold by importers and jobbers to country merchants.

Fortunately, large numbers of nineteenth-century invoices for ceramics sold to the country trade—stores in small towns and rural areas—have survived, and they provide a wealth of useful information. In 1790 the consumers serviced by these stores represented 90 percent of the population; in 1880, more than 40 percent.[18] Because they show the items ordered by a retailer, these importer and jobber invoices, practically ignored by researchers, give us an overview of the changing consumption patterns in the retailer’s entire community rather than within a single household.

Invoices to the country trade make it fairly easy to re-create community assemblages. For starters, they provide more precise chronological data than what can be deduced from excavations or probate inventories. Excavated assemblages constitute what was broken or lost over time, whereas probate inventories represent what survived. Both, however, are unreliable for determining what was used in a household, as it is not possible to know what was taken away from a particular site or what went unrecorded in a probate inventory. In contrast, vessels enumerated in invoices to the country trade represent a complete sample at a single point in time. The quantities of vessels listed in these invoices almost always far exceed what is itemized in a probate inventory or what can be recovered from the excavation of an individual household.

Before presenting the data taken from the invoices we have assembled, a discussion of the terminology used and some documented regional variations is required.

Potters’ and Importers’ Terminology and Regional Variations

The Staffordshire potters’ printed price-fixing agreements of 1783, 1787, 1795, 1796, 1804, 1814, 1825, 1833, 1846, and 1854 clearly show that the terms used to describe vessel forms, decorative types, and sizes had become very standardized. Although we do not have later price-fixing agreements, the descriptive terms used in potters’ invoices and price lists show that these terms carried through the nineteenth century.[19] Standard decorative types included CC (cream-colored), edged, dipped (or “dipt,” the Staffordshire potters’ term for slip-decorated wares, including mocha, common cable, and banded decoration), painted, printed, Egyptian Black (commonly called “black basalt”), and, later, white granite. Importers and jobbers used these terms consistently in their invoices to the country trade.

CC ware began as cream-colored ware and evolved into what archaeologists call whiteware. Undecorated Staffordshire wares made between the 1790s and the 1840s were listed as CC in price-fixing lists and importer invoices. CC ware was made throughout the nineteenth century, although in the second half of the century it was relegated to such forms as bowls, chamber pots, and other utilitarian wares. White granite was introduced in the 1840s and in general was vitrified, denser, and thicker than CC ware. It also evolved, however, and by the late nineteenth century it is not uncommon to find unvitrified white granite vessels. White granite is the term almost always used in the potters’ price-fixing lists for what collectors and archaeologists generally call white ironstone. This came about because the maker’s marks on white granite often include the name “ironstone” as part of the mark. Egyptian Black is a ware type as well as a decorative type. All of the other standard types—edged, dipped, painted, and printed wares—were classified by how they were decorated and almost never by the ware type. Combinations of these types, such as printed wares that are painted, occur occasionally but are not discussed here because we do not have enough information on them. The consistency of the terminology used by potters and importers is very reassuring. Terms such as China glaze, pearlware, and whiteware are almost nonexistent in price lists and invoices.

Queensware is the name that Josiah Wedgwood assigned his creamware after being appointed Potter to Her Majesty the Queen of England in the 1760s. The other potters were quick to pick it up, and the term was used generically by the Staffordshire potters to describe the types mentioned above (CC, edged, etc.) until at least 1787, possibly later. The header for the 1783 price-fixing list reads, “At a General Meeting of the Manufacturers of Queen’s Earthenware . . . ,” whereas the header for the 1787 price-fixing list reads “Prices of Queen’s Ware or Cream Coloured Earthenware established through the Potters.”[20] By the 1790s queensware as a generic term seems to have been dropped in favor of earthenware. For example, the header of the 1814 price-fixing list reads, “Prices Current of Earthenware, as agreed to at a General Meeting of the Staffordshire Manufacturers.”[21]

The term queensware continued to be used by American importers and jobbers long after it was abandoned in England. Prior to the 1830s most importers’ invoices to the country trade were handwritten and contained minimal information about the importer. Printed invoice forms, which first appeared in the 1820s, became common after 1830. These forms, or billheads, commonly had headers identifying the seller as an “Importer” or “Dealer” in either earthenware, crockery, or queensware, depending on the region. The invoices include the proprietor’s address, blank lines for the sale date, the buyer’s name and location, and varying degrees of additional information, such as the range of products offered for sale. These documents became more detailed over time and some included vignettes of pottery or a view of the importer’s store. Some invoices convey bits of a company’s history—“Founded in” or “Successors to,” for example—and some list specific Staffordshire potters for which the importer was acting as agent.

Printed invoices from importers in Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania show regional variations in which generic terms were used for the Staffordshire earthenwares: “Dealers in Earthenware, China and Glass”; “Dealers in China, Crockery and Glass”; or “Dealers in China, Glass and Queensware.” The distinct regional preferences between the terms crockery, earthenware, and queensware can be seen in Table 3, which lists the number of billheads and their date ranges.

Figure 1 shows an 1861 invoice from Davenport Brothers in New York— “Importers and Wholesale Dealers in China, Glass and Earthenware.” A plate with their importer’s mark is shown in figures 2 and 3. Other relevant examples of printed billheads are shown in figure 4 (figure 5 shows a pitcher that is a close match for the center vessel pictured in the figure 4 vignette) and figure 6. Figures 7 and 8 illustrate a deep muffin plate bearing the importer’s mark of Samuel Fahnestock, whose sons, known as the Fahnestock Brothers, ordered the wares sold by Stein, Wanner & Co. (see fig. 4).

While the information on terminology and classification is interesting, it is not as important as what can be gained by quantifying the ceramics listed in these invoices. An NEH grant provided an opportunity to compile 101 invoices to the country trade from New York importers dating from 1806 to 1886.[22] From these invoices data on teas, plates, and bowls—including quantity, description of the vessels, prices, and other information—was extracted. Before examining the resulting distribution of these vessels, however, it is necessary to provide some historical background on ceramics trade in the nineteenth century.

“A Plague of Plenty and Cheap”:

Economic Factors Affecting the Importation of Ceramics

During the War of 1812, English merchants stockpiled merchandise in Liverpool, Halifax, and Bermuda in anticipation of the eventual reopening of the American market.[23] Importers such as Horace Collamore of Boston and Matthew Smith of Baltimore were able to send orders to Staffordshire on cartel ships to England for the ceramics that they wanted shipped as soon as peace was declared.[24] Otis Norcross, a Boston importer, summed up the situation in a letter written in December 1815 to Staffordshire potter John Rogers: “We are well aware that the demand for ware will be immense for the next season which will overstock the market and then the succeeding years will be flat—flat—flat” (underlining in the original). Indeed, great quantities of English manufactured goods were shipped to America in 1815 and 1816. In 1816 Staffordshire potter J. Stubbs consigned 150 crates of his wares to the Boston auction market. This caused Norcross to write a letter to potter John Rogers complaining about wares being sent on consignment rather than waiting for orders from the importers.[25]

A number of authors have written about the flood of English manufactures to the American market after the War of 1812, describing it as a “dumping” of wares at below market prices in an effort to destroy the American industries that had sprung to life during the Embargo of 1807 and the War of 1812. As one historian put it:

It was decidedly to the advantage of British manufacturers to crush the numerous manufacturing industries which had arisen in the United States during the war of 1812. As stated at the time by a Member of Parliament, “it was well worth while to incur a loss upon the first exportation, in order to glut, to stifle in the cradle, those rising manufacturers in the United States, which the war had forced into existence, contrary to the natural course of things.” The British manufacturers, which comprised the bulk of the imports, soon glutted the American market, to the serious detriment of the many industries which had not as yet been so firmly established as to withstand sharp competition.[26]

In his book The Rise of the New York Port, 1815–1860, Robert Green Albion notes that the British apparently “settled upon New York as the best port for the bulk of their ‘dumping’ of manufactures. It seemed better for their purposes than Boston, where the British had played upon the anti-war feelings by tolerating a reasonable amount of leakage and which consequently had not been deprived of European goods to the extent of New York.”[27] Douglas North observes that “a combination of technological leadership, the ability of English manufacturers to dump upon the American market during the years 1815–1818, and the auction system . . . proved disastrous to a good deal of American manufacturing.”[28] And after the war, as John Dobson has pointed out, “much of this surplus was dumped on the U.S. market at prices far below original costs.”[29] These comments reflect a commonly held perception that in 1815–1816 English manufacturers had colluded to send goods at below market prices to America in order to destroy its emerging manufacturers.

Yet research shows that prices continued to fall following the so-called dumping of English wares, and that the prices fell in England as well as in the United States. Moreover, no one has presented evidence of the “dumping” as being a planned, coordinated activity.[30] David Hackett Fischer provides a better understanding of these events in his book The Great Wave: Price Revolutions and the Rhythm of History. He describes the 1790–1815 period as one in which prices soared in many nations, with increases greater than any previous price revolution. Following the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812 this cycle came to an end and was followed by a period of major deflation.[31]

To help finance the Napoleonic Wars the English government had received major loans from the Bank of England. The Bank of England and the country banks expanded the money supply by issuing paper currency that could be exchanged for specie (hard currency of silver or gold). By 1797, however, the banks suspended this exchange of banknotes for specie, which resulted in a hoarding of silver and gold coinage that precipitated a decline in the value of the paper currency.[32] Inflation—fueled by the expanded money supply, government borrowing and spending, and rising prices for scarce imported goods—was reflected in soaring prices. Prices reached their peak in 1814, at the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars.[33] Supplies that had been scarce and expensive during the wars suddenly became available at lower prices. Thomas Doubleday’s 1847 financial history of England nicely sums up the situation following Napoléon’s defeat: “The first trouble, which the ‘triumph’ of 1814–1845 brought upon the heads of the ministers and their supporters, was somewhat similar, being the plague of ‘plenty and cheapness’!”[34] (emphasis added). He continues:

Such was the state of the paper-money in 1815; and hardly had the echoes of the cannon of Waterloo died into silence, when it began to be felt that this state could not continue any longer. . . . Prices fell, on a sudden, to a ruinous extent—banks broke—wages fell with prices of manufacturers; and before the year 1816 had come to a close, panic, bankruptcy, riot, and disaffection, had spread through the land.[35]

Pressure began to mount to return the pound sterling to its prewar value. Economist David Ricardo published an influential pamphlet calling for currency stabilization.[36] Recognizing that foreign trade was negatively impacted if currency could not be converted into specie, by 1816 the Bank of England began to accumulate a gold reserve in anticipation of the resumption of making the banknote currency exchangeable with specie at par. It also curtailed credit, which had a deflationary effect on the economy.[37] In 1819 Parliament called on the Bank of England to resume specie payments.[38] Merchants who had incurred debts or accumulated large inventories when prices were high found themselves in financial crisis when falling prices diminished the value of their inventories. Many businesses and country banks went into bankruptcy, leading to a similar financial crisis for those who were owed money or had deposits in bankrupt institutions.

Prior to 1815 English merchants controlled most of the exportation of goods to the European and American markets. These merchants often had partners or agents in America and a regular set of jobbers and importers with whom they dealt, and they purchased the wares directly from the manufacturers for their American customers.[39] However, the surplus inventories accumulated during the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812 were more than the export merchants could handle, and flooding the market with goods was not a good business proposition. Therefore, in order to keep their factories in production and their workforce paid, many manufacturers began exporting wares at their own risk by consigning them to “commission merchants,” who received a fixed commission regardless of whether the wares sold at a profit or a loss. English commission merchants typically paid advances ranging from two-thirds to three-fourths of the value of the consigned wares,[40] which gave manufacturers the ready cash they needed until the wares were sold and the notes came due.

When goods arrived in a port, the commission merchant assigned them to an auction house for sale, a process that is described in an 1829 issue of the New York Assembly Journal:

On the arrival of their goods, the general practice [was] to hand over their invoices and endorse bills of lading to their auctioneer, leaving it to him to enter their goods at the custom house and give bonds for the duties. . . . [The auctioneers were] in the habit of making advances on goods so placed under their control, of an amount equal to two-thirds of their value, and to pay the balance on sales as soon as they [were completed].[41]

While having one’s goods sold by a commission merchant was a fast way to secure funds, if the goods sold for less than the amount advanced, the manufacturer could incur crippling debt. Indeed, some commission houses became known as “slaughter-houses” for driving some manufacturers into bankruptcy.[42]

Fortunately, we have a convenient measuring stick for documenting the fall of Staffordshire ceramic prices. In 1814, during the height of the inflation, the Staffordshire potters created a printed price-fixing list that reflected the high costs of production and the market conditions just prior to the end of the Napoleonic Wars. The prices given in that list were used consistently to price ceramics listed in the invoices for wares sent to America from the end of the War of 1812 into the 1850s. However, the percentage of discount given at the bottom of those invoices increased through time.[43] By 1816 the discount was 20 percent; from 1816 to 1830 it averaged 29 percent. By the 1840s the average discounts were 40 percent below the 1814 list,[44] which will be discussed later. Copies of the 1814 price-fixing list were sent to American importers and transcribed into the minutes of the Boston earthenware dealers association.[45] The lasting significance of this list is well illustrated by the 1846 printed revision of it, titled “Prices Current of Earthenware, 1814; Revised and Enlarged December 1st, 1843 and January 26th, 1846 in Public Meeting of Manufacturers.”[46]

Falling prices had a major impact on the choices that consumers made and, ultimately, on the quality of the wares produced. The prices of decorated wares were falling toward the cost of plain CC ware, which was the cheapest refined ware available. Figure 9 illustrates the declining cost for painted teas, dipped bowls, and edged plates toward the cost of CC ware from 1796 to 1859. For example, painted teas, which were 80 percent more expensive than CC teas in 1796, by 1859 had fallen to only 13 percent more. In the same period, dipped bowls went from costing 60 percent more than CC bowls to only 8 percent more, and edged plates went from costing 28 percent more than CC edged plates to only 5 percent more.

Staffordshire potters were pummeled by the “invisible hand” described by Adam Smith, a brutal price competition that grew out of the potters’ ability to produce more ceramics than the market could absorb. Throughout his Encyclopedia of British Pottery and Porcelain Marks (1964), Geoffrey Godden lists many companies that only briefly survived in this harsh market.[47] A long series of price-fixing agreements, dating back to 1770 and usually initiated in times of economic distress, when prices were falling (for example, in 1770, 1783, 1796, 1814, and 1846), were an attempt to keep prices steady. In theory the potters agreed to the prices set in the lists, but in practice many circumvented the list in a variety of ways—by making their vessels a bit larger than the listed size, by classifying wares as seconds in quality, or by giving a higher percentage of discount from the prices in the 1814 price-fixing list than that being offered by other potters. In addition to falling prices for all wares, the listed price for decorated wares was being lowered toward the cost of plain CC ware.

In an effort to control their local market, set prices, and deal with manufacturers who were sending wares to commission merchants to be sold at auction, importers of ceramics formed trade associations in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Fortunately, the minutes book of the Association of Earthen Ware Dealers of Boston has survived in the archives of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Covering the 1817–1835 period, the minutes refer to anti-auction activities, ranging from boycotts to attempts to purchase all of the consigned ceramics at an advance over import costs or to appoint one or two of their members to attend the auction and bid on behalf of the association to limit internal competition among the dealers and to purchase the wares selling below market prices.[48]

In May 1842 the Importers and Dealers in Earthen Ware in the City of New York sent a printed circular to various Staffordshire potters concerning the consignment of wares to the auction market. The circular, which names thirty-eight New York importers, states:

We allude to the system of Consignment of your products to the American market, for sale on your own account . . . . This system is so utterly at variance with the correct principles of the trade, viz. that “demand should regulate supply.” . . . Such is the uncertainty as to the quantity of goods that may be thrown on the market for an immediate and forced sale, that we have no confidence that we can order direct from you, without running the risk that articles of an equal value may be forced off at auction, at a far less sum than our own costs to import.[49]

The sending of ceramics on consignment to be sold at auction seems to have been much more common during periods of economic panic, such as 1819, 1837, and 1857. War, embargoes, economic panic, deflation, and inflation are all elements that affect ceramic consumption patterns. The impact of various economic events can be seen in figure 10, which shows the value of English ceramics imported to the American market from 1828—when these statistics began being reported—to 1886.[50] It is easy to see the drop in export value during the Panic of 1837 (which lasted until 1843) and the steep decline that took place during the Civil War. The dip in the 1870s occurred when England began to lose market share to ceramics from other countries and when the emerging American ceramics industry began supplying local markets. Figure 11 illustrates the English market share of imported ceramics. Treasury records for ceramics imports began in 1828, but it is clear that England was the dominant source of American imported ceramics well before then. Its market share went from 96 percent in 1828 to 57 percent in 1890.

One of the problems for those studying ceramics is that market share and dollar values do not easily translate into vessels, though clearly, with prices falling, the number of vessels per dollar was going up. The percentage of the market for each country probably would be different if it were possible to know the number of vessels represented by the dollar value. For example, the imports from France probably included a lot of porcelain that was more expensive than English earthenware. If we knew the number of vessels and ranked the market that way, the English share of the import market would be at a higher level than the dollar share.

Given all of these complex factors, it is probably naive to think that our sample of 101 invoices from New York importers to the country trade is large enough to reflect these continuing changes in the ceramics market. Nevertheless, it is a start.

Table 4 presents the distribution of invoices grouped by years according to economic conditions. There are periods for which we do not have invoices: 1807–1814, 1828–1829, 1849–1850, 1864–1866, and 1874–1881. If the number of invoices had been large enough, they would have been listed by year, but given the limitation it was felt best to bundle them together based on the best estimate of the economic conditions of the periods in which they were created. The second reason for bundling the invoices was to generate an adequate sample size to even out the distribution of the teas, plates, and bowls. Because there were five invoices for 1860, it was decided that year did not need to be lumped with other time periods. From Table 4 it can be seen that the numbers of teas, plates, and bowls represent a sizable sample for almost all of the grouped periods in this study.

Impact of the American Civil War

As in the period following the War of 1812, the deflation that followed the Civil War brought about changes in ceramic consumption patterns that must be understood in the economic context of the period. From the 1790s through most of the nineteenth century the American monetary system was bimetallic—that is, both gold and silver constituted legal tender at a predetermined ratio. Under that system, the dollar’s exchange rate in English pound sterling fluctuated around $4.80. In February 1862 Congress issued $150 million in “greenback” currency, paper money that was to be considered legal tender for all debts with the exception of import duties, which were to be paid in specie—coin, or hard, currency.[51] Tariff duties were the U.S. government’s primary revenue source before the establishment of an income tax in 1913, and hard currency was needed to help finance the Civil War. This hard currency requirement also helped suppress the volume of imported goods.

Five months after greenbacks were put into circulation in 1862, there was a 20 percent premium on the gold dollar. Proving the maxim that “bad money drives out good,” gold and silver coin currency was hoarded out of circulation.[52] At one point in the 1860s the value of the English pound rose to $7.00, almost 46 percent higher than its prewar value.[53] Figure 10 shows that the importation of English ceramics dropped significantly in 1862, which is when Civil War inflation began. Another major factor in this decrease was the Union naval blockade of the South, which cut off a major part of the American market for imported goods and nearly eliminated the cotton trade that generated much of the income used to buy imported goods. Congress also increased tariffs on a variety of goods to help pay for the cost of the war.[54] The U.S. tariff rates on ceramics in 1862 and 1864 are given in Table 5.

The higher exchange rates and increased tariff costs created a turning point in the types of wares being imported from mostly those with decoration to white granite wares. These changes are illustrated in figures 13 through 18. Figure 12 is a transcription of a printed notice dated July 1, 1864, from D. B. Stedman and Co., a Boston importer, to his country trade customers announcing a 50 percent advance in his prices.[55]

It was during the Civil War that the American pottery industry went through a takeoff period. The high exchange rate of the dollar to the English pound, the requirement that tariffs be paid in hard money, and the high tariff level all played a part in this development. The Staffordshire pottery industry was in the doldrums from the drop in exports, and it was during this period that many English pottery workers migrated to the United States to work in Trenton, New Jersey, and East Liverpool, Ohio.

Purchase Patterns for Tea, Table, and Kitchen Wares

Beyond the impact of economics on distribution, it is important to keep in mind the purchasing patterns that existed for teaware, tableware, and kitchenware. Staffordshire potters’ price-fixing lists group tablewares and teawares separately, usually followed by bowls, mugs, jugs (the English term for pitchers), and toilet wares. All of these functional wares were available in CC and printed ware. However, some of the decorative types were almost always limited to one of the functional groups. For example, edged wares were tableware; painted wares were primarily teaware; and dipped wares were limited to hollow wares such as bowls, mugs, jugs, and chamber pots. When tea drinking was introduced in England, it was not part of dining but a separate activity.[56] The combination of teawares and tablewares into large matched services does not become common until the 1880s. Such services, ranging from 80 to 110 vessels, with matching teas, plates, and bowls, began to be listed in Montgomery Ward, Sears and Roebuck catalogs, and other sources at this time. These large services commonly were offered in white granite or printed wares and later in bone china and Continental porcelain.

Because purchases of teas, tablewares, and bowls were independent of each other, the quantifications of the changing mix of these wares offer insight into how consumption patterns were affected by economic events and falling prices. Our study documents that changes in teaware purchases generally preceded changes in the purchases of tablewares, and bowl purchase patterns changed the least.

Distribution of CC and White Granite Teas, Plates, and Bowls, 1806–1886

To see the difference in purchasing patterns one can look at the changing proportion of undecorated plates, teas, and bowls listed in the invoices. By the 1790s creamware had devolved into what the potters called CC ware. It was undecorated and the cheapest type available. The ratio of CC wares to decorative ones, which varies considerably between teas, plates, and bowls, reflects different purchase patterns and the roles that these functional types played over time.

“Teas” in the Staffordshire price-fixing lists, invoices, and the importers’ invoices refers to cups and saucers. Teas listed in the invoices to the country trade show the lowest ratios of CC ware purchased, followed by plates and bowls. Figure 13 shows that sales of CC teas were very low prior to the Embargo of 1807, and they do not reappear in the invoices until after the Civil War. White granite (WG) was the other undecorated ware, though it came in a great variety of molded patterns. It first appeared in the early 1840s and dominated during the Civil War and into the 1880s. CC and WG teas have been plotted as the undecorated wares. Decorated teas were the dominant types after the War of 1812 until the Civil War.

CC plates continued being sold into the early nineteenth century, long after the market for CC teas had ended (fig. 14). Our data suggest that CC plates were the dominant type until about 1820, by which time shell-edged plates became most common. CC plates reappeared during the Civil War, with inflation and high tariffs. Some of the later CC and WG wares might have been made in America, as both wares appear frequently on American potters’ price lists and invoices. As with teas, white granite plates were, as with the teas, the dominant type following the Civil War.

The distribution of undecorated bowls provides a further contrast with that of teas and plates (fig. 15). CC bowls were purchased throughout the period 1806–1873, and in general they represented more than 30 percent of all the bowls being sold. The impact of white granite in bowl sales is much more limited. Bowls played a dual role of food preparation and food service; given their utilitarian nature, the desire to have them with decoration was not as strong as for teas and plates.

Decorated Teas, Plates, and Bowls

Declining ceramic prices brought about by deflation following the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812 neatly correlates with a shift in consumption patterns. Figure 16 shows that from 1815 to 1861 painted and printed teas constituted between 70 and 100 percent of these wares. This is followed by a dramatic shift to white granite teas, which became dominant from 1862 to 1886, correlating with the inflation brought about by the Civil War, the unfavorable exchange rate for the pound sterling, higher tariffs, and the development of an American ceramics industry. American-made white granite became more common on American sites after the 1870s.

Painted teas, dominant until the beginning of the Civil War, were the least expensive teaware with color decoration. In today’s antique market painted teas are scarce, whereas printed teas are very common. This has led to the misconception that printed teawares dominated in the nineteenth century. Clearly, the antique market is skewed toward the more expensive wares, which suggests that the archaeological assemblages are skewed toward the less expensive wares.

Teas constitute a significantly greater proportion of decorated ware than do plates and bowls (figs. 16-18). This can be seen in the average cost of these wares above the cost of CC ware. Table 6 shows the average percentage above the cost of CC ware for vessels sold by George M. Coates, a Philadelphia earthenware dealer, to country merchants.[57]

Shell-edged plates (listed as “edged”) were the dominant type for most of the periods between the wars until both edged and printed plates gave way to white granite. Again, the economic conditions brought on by the Civil War appear to have ended the life cycle for edged wares. Printed wares also died out but only temporarily, making a comeback after the 1870s. While not reflected in the invoices in our sample, this is known from archaeological assemblages from that later period (fig. 17). Because edged plates were cheap and common, a relatively small percentage of them has survived. In contrast, as with painted teas, printed plates are commonly seen on the antiques market and therefore have been misconstrued to be the dominant type.

CC bowls were purchased throughout the 1806–1886 period and in general represented more than 30 percent of the bowls being purchased. Decorated bowls begin to dominate by the late 1820s, but there were three common decorative types, rather than the two types available in teas and plates. Painted bowls remained common until the mid-1830s, at which point the dipped wares surpassed them in popularity. Dipped wares were the cheapest type of bowl with color decoration and are almost always hollow wares, such as bowls, mugs, pitchers, and chamber pots.[58] Printed bowls were relatively rare (fig. 18).

Life Cycles of English Pottery Types

In her 1994 article on declining English textile prices, Carol Shammas shows that between 1816 and 1859 the cost of cotton sheeting fell slightly more than 60 percent and cotton check fell about 64 percent.[59] When comparing textile prices over time, she astutely observes, “[i]t has to be admitted that the numerous grades of any given fabric make it difficult to chart prices because of the impossibility of knowing whether a particular named cloth in one year is the same quality and type 50 years later.” Shammas and other material researchers face the difficulty of finding surviving examples of the range of material being produced over time. Museum collections are rarely representative of the range of what was produced because of their approach to collecting. The connoisseurship approach to material culture often defines wares that are worthy of acquisition and curation according to a scale of “Good, Better, Best.” Even the “Best” drops down the scale of appreciation if it has been broken and mended, since most museums and collectors are focused on collecting vessel “virgins” that have survived the ravages of time. Context information for most museum objects is usually limited to where the object was produced and when it was made. Adding to these difficulties is the fact that most types of material culture do not survive in the ground or have been heavily recycled. Metal artifacts are underrepresented in archaeological assemblages because they had value as scrap and thus could be sold for money. Textiles were also recycled, to an extent—cotton rags, for example, were collected for making paper, and wool rags could be used to make shoddy, a cheap type of cloth. Common, cheap objects rarely were considered heirloom items, and thus their survival is rare.

Because of their intrinsic characteristics, ceramics present an opportunity to study an evolving product that is unmatched by almost all other types of material culture. Ceramics have long been studied by collectors, curators, and social historians who have access to historical documents as well as surviving pieces, which has yielded a massive body of literature on the subject. Excavations over the past half century have produced a plethora of ceramic assemblages ranging from the seventeenth through the twentieth centuries and from all economic classes. Thus, we have documents and examples of the wares described in them as well as contextual information tying them to the consumers.

It is the combination of documents and objects that enables us to look at pottery life cycles and follow the declining demand caused by the invisible hand of price competition. Whenever a successful new ware or decorative type was introduced, its life cycle began. The other Staffordshire potters were quick to produce their versions of the product, and, in order to gain competitive advantage, they would find ways to produce it less expensively or to sell it for less money. This often led to such a debasement of the product that, even at lower prices, there was no longer a demand for it. As shown in figures 27 and 28, the prices of the decorated wares were being brought down to the cost of CC ware over a period of roughly sixty years. If one had only the documents, it would appear that these wares were getting cheaper, but there would not be any evidence of the impact of lowering the prices on how the wares changed over time.

The Staffordshire potters’ price-fixing lists from 1796 to 1859 document the standard types—CC, edged, painted, dipped, printed, and later white granite. These types and the terminology used to describe them are consistent in the price-fixing lists, potters’ invoices, and importers’ invoices for wares sold to the country trade. Noticeably absent from these types of documents are terms such as pearlware (that great pigment of our imagination) and whiteware. Vessels are not specified as “hand” painted, because by hand was the only way things got painted; by the same token, vessels are not specified as “transfer” printed, but rather just called printed. While the terminology was fairly fixed, the wares were evolving. All of these wares went though a process of simplification (some would say debasement) that helped cut production costs and selling prices during the long period of deflation, which is what will be illustrated in the rest of this paper.

Edged Wares

Simplification of the molded edges to blue- and green-edged plates from the 1770s to the 1860s has been documented by Miller and Hunter.[60] Early edged wares had elaborate rococo molded rim patterns that by the 1790s had become simplified and by about 1810 gave way to an edged ware with even-scalloped rims. In the 1820s embossed-edged wares were introduced in an attempt to bring the prices up, but that short-term measure failed as the embossed-edged wares were soon selling at the same price as the regular edged wares. By the 1840s unscalloped-edged plates with simple molded patterns were replacing scalloped-edged wares, and by the 1850s unmolded edged wares were taking over. In the 1780s edged plates were 67 percent more expensive than CC plates; by 1866 that ratio was down to only 12 percent more expensive.[61] One can imagine the resistance to paying more for edged plates because of the inflation brought about by the Civil War when prices for these wares had been falling during the previous two decades.

Dipped Wares

Slip decoration on creamware and pearlware was a carryover of the traditional Staffordshire slip-decorated wares that were made on buff-firing coarseware bodies from at least the 1660s. When traditional slip decoration was extended onto creamware, it continued to use different types of clays to provide color decoration. This was an easy transition for the Staffordshire potters because they already had the colored clays, tools, and techniques to apply the decoration to creamware. Slip clays were sometimes darkened by adding such things as finely ground blacksmith’s iron scale. The resulting colors are generally earth tones of tan, buff-yellow, brown, and dark brown; blue and other mineral colors are rather rare. Dipped styles of decoration continued to be produced on creamware into the 1820s, when almost all other decorative types had the blue tint of pearlware. For example, edged and painted wares are rarely found on a creamware body after about 1785.

Dipped wares were the cheapest hollow ware available with color decoration. In some invoices and account books they are listed as “colored” ware. The price for dipped bowls, like edged plates, was 8 percent higher than CC bowls in 1859, whereas in the 1790s it had been 60 percent higher.[62] Like edged wares, the dipped wares became simplified over time. From the 1840s on they were mostly decorated with simple blue bands. Figure 19 illustrates complex dipped wares with variegated, fan, and mocha decoration. Variegated is a term for a type of dipped ware that was made by the early 1780s but seems to have gone out of production before 1800. We do not know what the potters called the “fan” pattern. Fan pattern is a descriptive name given to this type of decoration by collectors. This type of decoration dates mainly from about 1780 to 1820. Mocha began being produced in the mid-1790s and was in production into the early 1840s. Later mocha was produced on yellowware into the early twentieth century. These once cheap wares are rare and expensive on the antiques market, which is why examples in our collection are reproductions by Don Carpentier.

Dipped wares are well documented in Jonathan Rickard’s Mocha book and in an article by Carpentier and Rickard that illustrates Carpentier making some of these reproductions.[63] By the 1840s the elaborate dipped wares were giving way to “banded” dipped wares, which had simple blue bands. Figure 20 shows two blue-banded dipped bowls: the one on the left has been turned to make it thinner and to give it a sharper profile; the one on the right has been produced on a jolly and is much thicker. The inflation and rising prices brought about by the Civil War no doubt had an effect on the amount of dipped wares being imported in the postwar period.

Painted Wares

Underglaze blue painting went through a takeoff period beginning in the mid-1770s, due in part to the setting up of ovens to refine cobalt in Staffordshire and access to Cornish kaolin clay and Growan stone. Access to these materials came about in 1774, when Richard Champion applied for an extension of Cookworthy’s 1768 patent on the production of porcelain that was only partly successful. Parliament extended the patent, which gave Champion a monopoly in the production of hard-paste porcelain. The renewed patent made the clays and Growan stone available to everyone, however, as long as they did not use them to make porcelain. As a result, the Staffordshire potters knew how to make porcelain and had access to the materials but were prohibited by the Champion patent. During this period the Worcester porcelain factory began to move from painted to printed wares, and a number of the displaced “blue painters” wound up in Staffordshire. The success of creamware caused a downsizing of the English porcelain industry that added to the availability of trained painters. By the mid-1770s the market for undecorated creamware began to decline and the Staffordshire potters looked for a new product. The product they came up with was termed China glaze. It had a blue tint to the glaze and was painted in Chinese-style patterns; in short, it was an imitation of the porcelain they were barred from making because of Champion’s patent. This transition is documented and discussed in Miller and Hunter’s “How Creamware Got the Blues: The Origins of China Glaze and Pearlware,” published in the 2001 volume of Ceramics in America.[64]

Wedgwood’s refinement and brilliant marketing of creamware elevated this earthenware to a status that made it competitive with porcelain, a process well documented by Neil McKendrick.[65] For creamware to compete with porcelain in status, it could not be a copy of Chinese or other porcelain, and Wedgwood avoided such imitation. When he built his new Staffordshire pottery, Wedgwood called it “The New Etruria” and focused on classical Roman and Greek designs. By contrast, the Bow porcelain factory was called “The New Canton” and focused on Chinese-style patterns.[66]

Because China-glaze wares were copies of porcelain wares, they could not compete in status and, once again, the Staffordshire earthenwares were second class to porcelain. Under the pressure of the market, Wedgwood produced what he called “Pearl White,” and after publication of Ivor Noël Hume’s 1969 article “Pearlware: Forgotten Milestone of English Ceramic History,” any ware with a blue-tinted glaze has been called pearlware.[67] Minimal reference was made to pearlware before that article, but it went on to become a “pigment of our imagination.” Archaeologists, collectors, and curators talked of pearlware replacing creamware, but in actuality it was decoration that replaced creamware. This should be clear from the distribution of decorative types for teas, plates, and bowls we have presented. The terms China glaze and pearlware do not appear in the Staffordshire potters’ price-fixing lists, potter invoices, importer invoices, or any other such records. One must bear in mind that the vast majority of creamware, with the exception of some dipped wares, was undecorated. Pearlware, however, is rarely found without decoration, so the potters and merchants listed the wares by how they were decorated—that is, edged, dipped, painted, and printed.

The Life Cycle of Painted Teas

Painted teas were the dominant type from 1806 until the Civil War (see fig. 16). From 1806 until 1843 they constituted between 64 and 83 percent of the teas that were purchased. According to the invoices, sales of painted teas fell from 80 percent in 1860 to just over 21 percent in 1862–1863 and practically disappear thereafter. As with edged and dipped wares, the price of painted teas fell over time, in part because of deflation following the Napoleonic Wars but also because of fierce price competition brought about by periodic market gluts. In 1787 painted teas cost 150 percent more than CC teas; by the 1860s they cost only about 17 percent more. From the return of peace in 1815 and into the 1850s the price of Staffordshire wares gradually fell, as the discount off the 1814 price list went from 25 percent in 1816 to an average of 40 percent by the 1840s.[68] If the sole source of our information was the documents, all that could be said is that the prices for teas were going down. However, surviving contemporary objects enable us to track modifications in the wares against the falling prices.

Unfortunately, painted teas rarely have makers’ marks or pattern names, which makes it difficult to date surviving vessels and to place their manufacture in chronological order. When blue-painted China-glaze wares were introduced in the mid-1770s, they were produced as table- and teaware (fig. 21). In her recent publication Painted in Blue, Lois Roberts illustrated hundreds of blue-painted China-glaze decoration on a variety of vessel forms.[69] None—either marked or dated—is a cup or saucer. The dates on the vessels range from 1778 to 1800; most are in the 1790s. After 1800, however, a change took place and painted tablewares became much less common. This might have been due to the introduction of underglaze-blue transfer printing in the mid-1780s. Painted tablewares do not appear on any of the potters’ price-fixing lists from 1796 to the 1850s, whereas all list painted teas. For most of the nineteenth century, painted decoration was limited to teawares, bowls, and other hollow wares.

In 1796 painted teas cost only 80 percent more than creamware teas, but printed teas cost 240 percent more.[70] As the prices of printed wares fell, the decoration of painted wares was forced to become less labor intensive, resulting in simpler patterns. By 1810, if not a bit earlier, blue floral-painted pearlware patterns began to replace China-glaze patterns. They are difficult to date because they were so rarely marked, though occasionally we find marks from some of the larger manufacturers, such as Davenport, Enoch Wood, William Adams, and R. & J. Clews. Blue painted pearlware teas (fig. 22) apparently were the most common type from after the War of 1812 through the 1820s.

Blue floral-painted teas were in production during the transition from pearlware to whiteware. Blue tinting in the glaze is easy to see in the earlier teas; the later ones can be very white in their background. Archaeologists, collectors, and curators are obsessed with this transition and have made it a major part of their classification system. This transition appears to have been a very minor event in the Staffordshire potters’ minds. The term whiteware, like the terms China glaze and pearlware, is almost nonexistent in the price-fixing lists, invoices, and correspondence of the Staffordshire potters, where the wares were classified by how they were decorated—edged, dipped, painted, or printed. In addition to not being found in primary documents from the potteries, pearlware and the transition to whiteware is not very well documented in the histories of the potteries and collector literature. In his Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America, Noël Hume gives 1820 as the beginning date for whitewares, and that is the date cited most often. One cause for the switch to a whiter-looking ware appears to be the success of Josiah Spode’s bone china in the English market. Introduced about 1800, it was more translucent and whiter than Chinese porcelain. The Wedgwood Company developed a whiteware by 1805. The following letter from a Wedgwood salesman named Bateman, who sold wares to English merchants, conveys the impact of Spode’s bone china:

Cheltenham April 15th 1810

Our white ware enameled patterns stick on hand, the dealers say they never can dispose of them, it is admitted it surpasses any thing of the kind, but when the customer holds it up to the light to find a transparency they exclaim it is not china, and feel disappointed, of course they give preference to a daubed thing bearing the name china.[71]

It appears that the Staffordshire potters switched from copying Chinese porcelain with their China-glaze ware to copying Spode’s bone china with whiteware. Earthenware, competitive with porcelain when creamware was new, was now back in second place.

Where pearlware ends and whiteware begins will always be difficult to ascertain. When the glaze has no bluing the identification is easy, but when the blue tint was added to make the ware look whiter we are left to interpret the objective of the potter. Given the large number of potters producing these wares, it is not surprising that the methods used to make a whiter ware varied. In any event, the transition from pearlware to whiteware is not nearly as clear and as important as the transition from creamware to China-glaze ware.

Polychrome Painted Teas

The Staffordshire potters’ price-fixing list dated April 21, 1796, lists “Blue and Painted Ware in Colours Under the Glaze,” indicating that they were introduced sometime before that date.[72] The new palette of “high temperature colors” included brown, tan, olive green, yellow, and mustard yellow, in addition to the cobalt blue already in use. The colors are muted by the blue tint of the glaze. The vast majority of polychrome painted pearlwares are floral painted, and China-glaze polychrome wares are rather rare. Printed wares in this period were done almost exclusively in blue, and the polychrome wares thus went into an area where the printed wares were not able to go. A number of the early polychrome painted wares copied classical enamel-painted patterns that had been used by Wedgwood and others on creamware from at least the 1770s. Polychrome floral-painted pearlwares were very common from the 1790s until about 1830, when the chrome colors seem to make their appearance on a much whiter ware. Pottery importers’ invoices rarely distinguish blue-painted from polychrome-painted wares, so the painted wares in figure 16 would be a combination of blue- and polychrome-painted teas. Notice how much of the surface area was left undecorated (fig. 23). As the century progressed the painting became less complex, with simple repetitive floral patterns requiring fewer brushstrokes as a way to cut production costs and cope with falling prices.

Introduction of Chrome Colors

In the late 1820s a new color palette for underglaze painting and printing appeared in Staffordshire. In the preface to his 1829 History of the Staffordshire Potteries Simeon Shaw states:

Very recently several of the most eminent Manufacturers have introduced a method of ornamenting Table and Desert Services, similar to Tea Services, by the Black Printers using red, brown, and green colors, for beautiful designs of flowers and landscapes; on Pottery greatly improved in quality. . . . This pottery has a rich and delicate appearance, and owing to the Blue printing having become so common, the other is now obtaining decided preference in most genteel circles.[73]

These are the chrome colors, which had advantages over the older mineral colors. They expanded the range of available colors and could be fired at higher temperatures. Shaw states that the chrome green “without injury sustains any temperature to which it may be requisite to raise the ware” and remarks that “None of the ancient yellows was so durable, brilliant, and beautiful as this chrome yellow.”[74] The chrome colors are almost always found on whitewares (fig. 24) so the colors are not mutated by a blue-tinted glaze as is the case with polychrome-painted pearlware.

By the early 1830s new painted patterns in teas were being introduced that required much less color and very few brushstrokes. These were called “sprig” or “sprigged” patterns in advertisements and invoices. The earliest known mention of sprig teas is in an advertisement of September 10, 1831, from R. Wright, of Washington, D.C., which listed “printed and sprigged tea china” that might have been on porcelain.[75] An invoice from New York importer Joseph Cheesman and Son from April 14, 1841, lists “Sprig Teas.”[76] Sprig painting became common on whiteware teas from around 1835 until the beginning of the Civil War. They occur after that but are not as common, and none was listed in the invoices used in this study from the later period. Figure 25 is an example of how small the sprig painting became during the period circa 1835–circa 1860. Sprig patterns could be painted faster than any of the previous floral patterns and used a lot less color. It is about this period that painted plates reappear, also painted in sprig patterns. It is almost as if one were watching the stylized flowers shrinking in size.

Another approach taken to reduce the amount of labor and skill in painted teas was to use sponges that had been cut in patterns. They were used like rubber stamps to apply simple patterns to the vessel. Figure 26 shows a saucer decorated by using four cut sponges.

The introduction to England of cut sponges, attributed to Scottish potteries, occurred about 1845, when a Scottish worker familiar with making cut-sponge patterns was brought to the William Adams factory in Greenfield. William Hancock, the manager of the art department, was able to keep the process secret for some time.[77] Cut-sponge–decorated wares with Adams marks are fairly common. In 1866 James Torrington Spencer Lidstone published his The Thirteenth Londonaid: Giving a Full Description of the Principal Establishments, &c. in the Potteries, in which a poem describing William and Thomas Adams is reproduced. The following lines from it shed some light on wares decorated with the cut-sponge technique:

It shows our House is far from being weak

When it makes 73,000 dozen Plates per week.

With terms in Art I hope I am acquainted—

Their Sponge, so good, I could not tell’t from Painted![78]

The various cut-sponge patterns on these wares are usually connected with some degree of painting and usually are classified as painted teas. They became common from the late 1840s through the rest of the nineteenth century, although, surprisingly, the invoices used for this study do not list any after the 1860s. Sponged teas in 1848–1858 cost 50 percent more than CC teas, but by 1871 they cost only 16 percent more, about the same as painted teas.[79]

In summary, painted teas were the cheapest type available with color decoration. From the invoices used in this study, it is clear that they were the dominant teas from 1806 until the Civil War. In 1787 they cost 150 percent more than CC teas, whereas by 1871 they cost only 15 percent more.

Printed Wares

Unlike edged (plates), painted (mostly teas), and dipped wares (mostly bowls), printed wares were not limited to particular vessel forms. Given that they were generally the most expensive type listed in the invoices, it is not surprising that they almost never appeared in the greatest numbers. As can be seen in figures 16, 17, and 18, printed wares were most common in teas and least common in bowls, with plates falling in between. Figure 27 shows printed wares had a more dramatic price fall against that of CC wares than did the other decorative types (see fig. 9).

As the price of printed wares fell toward that of CC wares, it squeezed the prices for painted, edged, and dipped wares and was a force in the reduction of their market. Figure 28 plots the declining price of printed (1796–1855) and edged (1787–1855) plates toward the cost of CC plates. Knowing that by the 1850s the price for printed plates was only slightly higher than that for edged plates makes it easier to comprehend why shell-edged plates are rather rare after that period.

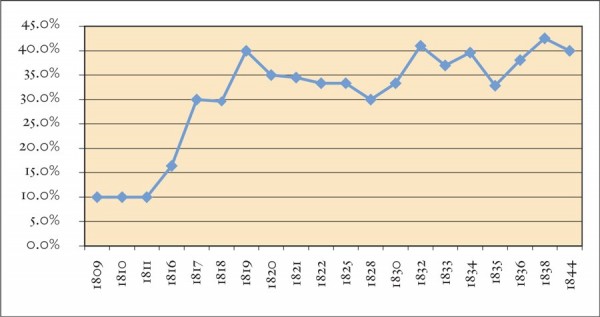

In figure 28 the price of shell-edged and printed plates are indexed to the cost of CC plates, which is why the CCs plot as a straight line. In fact, however, the prices for all ceramics were falling, which can be seen from the percentage of discounts from invoices for English ceramics sent to America.[80] Figure 29 presents the average discount from 122 invoices of English ceramics sent to America from 1809 to 1844. Eight invoices from 1809–1811 show the traditional discount—10 percent, to cover breakage and for cash payment—then the discount percentage rose sharply with the deflation that followed the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812. The discounts from 1814 to the 1850s—based on the prices listed in the 1814 Staffordshire potters’ price-fixing list—were calculated from the totals at the bottom of the invoices. When the 1814 list was revised in 1846, its header read: “Prices Current of Earthenware, 1814; Revised and Enlarged December 1st, 1843, and January 26th, 1846, in Public Meetings of Manufacturers.”[81] While the prices of all ceramics were falling, those for printed wares fell the most, from nearly 400 percent more expensive than CC ware to only 50 percent more (figs. 28, 29).

Fortunately, more information is available on the evolution of printed wares than of the other decorative types. A higher proportion of printed wares have maker’s marks, and many include a pattern name. After 1842 commercial designs could be registered in the London Patent Office, and registry marks are helpful in tracking style changes.[82] Several books have been published on printed wares tracing the origins of the patterns. Patricia Samford drew on these sources to create a seriation of the changing styles in printed wares from the 1790s to the 1890s.[83]

When blue-printed wares were introduced into Staffordshire in 1784, they imitated Chinese porcelain—a blue-tinted glaze, Chinese-shaped cups and bowls, and Chinese-style undercut footrings. These China-glaze printed wares were the most common types until about 1815. A large number of these patterns have been illustrated in Robert Copeland’s Spode’s Willow Pattern and Other Designs after the Chinese.[84] Figure 30 shows a blue-printed China-glaze plate by Turner of Lane End, Longton, who went bankrupt in 1806 because he was unable to collect money owed from French importers due to turmoil in France and the Napoleonic Wars.

By the second decade of the nineteenth century, the potters began to copy prints found in travel accounts and other sources. These wares, which made minimal effort to look like Chinese porcelain, were common until 1842, when the British Patent Office began a registry of designs that gave them a form of copyright protection.[85] The plate illustrated in figure 31, probably by J. and R. Riley of Burslem, is a composite of two street-scene prints from Oriental Scenery by T. and W. Daniell.[86]

Views of British and American landscapes and historical events began appearing on printed pearlware plates, and those produced from about 1818 to 1830 were often in a very dark blue created by use of negative patterns or by filling in the background with small engraved circles (fig. 32). This period of copying published artwork was followed by the production of imaginary exotic and romantic views with floral and Gothic patterns, created by embellishing elements taken from a variety of sources, among them the imaginations of artists and engravers in the potteries. The resulting patterns were less complex than the earlier ones and had a lot more white space between the central view and the pattern on the marley. Figures 2, 7, and 33 all show a white space between the marley pattern and the central design. This was the dominant style for printed wares from about 1835 to 1860. Using larger white areas reduced both the engraving time and the amount of the color oxides used to print the pattern from the copperplates.

One of the ways potters reduced their productions costs that facilitated reduction of the prices of printed wares was to use sheet patterns; like wallpaper, they do not have a border and the whole object is covered with a continuous pattern. The same sheet pattern could be used to decorate any type of vessel and thus cut down on the number of engraved copperplates required to decorate a range of vessels. Although Spode had produced some sheet-pattern printed wares by about 1812, they were more common after about 1850.[87] The later sheet patterns have simple repetitive patterns (fig. 35).

Further cost cutting was achieved by using patterns of small sprays or vignettes that were applied to the marley and other areas of the vessel. These required fewer engraved copperplates to decorate a variety of vessels than the earlier, more complex patterns. Printed wares with small vignettes and/or floral sprays become more common in the second half of the nineteenth century (fig. 36).

Ernest Albert Sandeman’s 1901 book on the manufacture of earthenware nicely sums up the ways in which costs could be cut for printed wares:

Care must therefore be taken in deciding on new patterns that, besides being effective, they can be arranged in a suitable manner of the copper for working. Formerly, patterns were designed in such a way that it was necessary to have a copper plate for every individual piece, and thus to print a full dinner service twenty to thirty coppers was required; with proper arrangement four or five coppers should now be sufficient for doing the same work, as the patterns most in demand are sprig and flower patterns, which one copper will suit several different purposes. If, in arranging a pattern, pieces of sprig, &c., have to be cut off, it is well to see if these bits cannot be applied to some other ware, such as bowls, basins &c, which is of advantage to both the manufacturer, as he uses up prints which would otherwise be wasted, and to the printer, as he thus does more ware with the same amount of work.[88]