Charles Chamberland (1851–1908). (Courtesy, Institut Pasteur.)

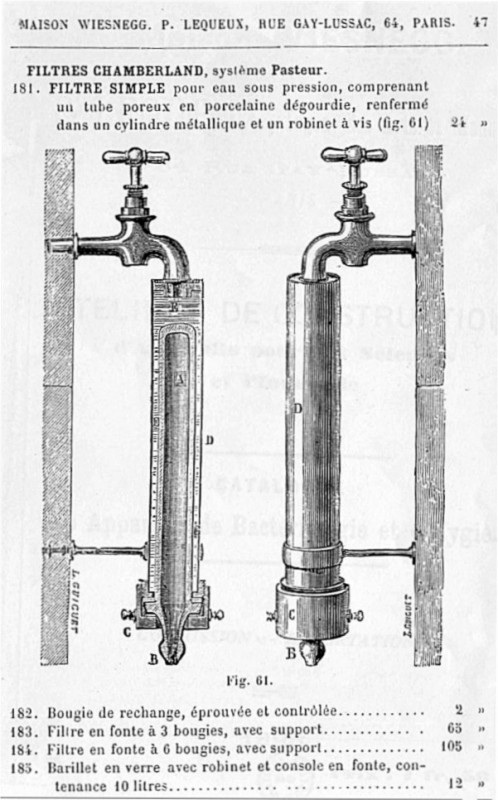

“Filtre Chamberland, Système Pasteur,” 1894 U.S. patent drawing.

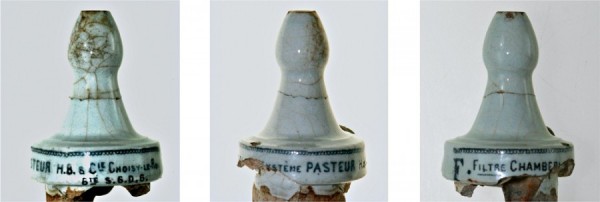

Filter nipple for the “Filtre Chamberland, Système Pasteur,” Choisy-le-Roi, after 1884. Porcelain. H. 1 5/8". Marks: “F: FILTRE CHAMBER[LAND] . . . [S]YSTÈME PASTEUR . . . H. B. & CIE CHOISY-LE-ROI / BTÉ S.G.D.G.” (Photos, the author.)

Filter sherds, including the porous bougie and the glazed nipple.

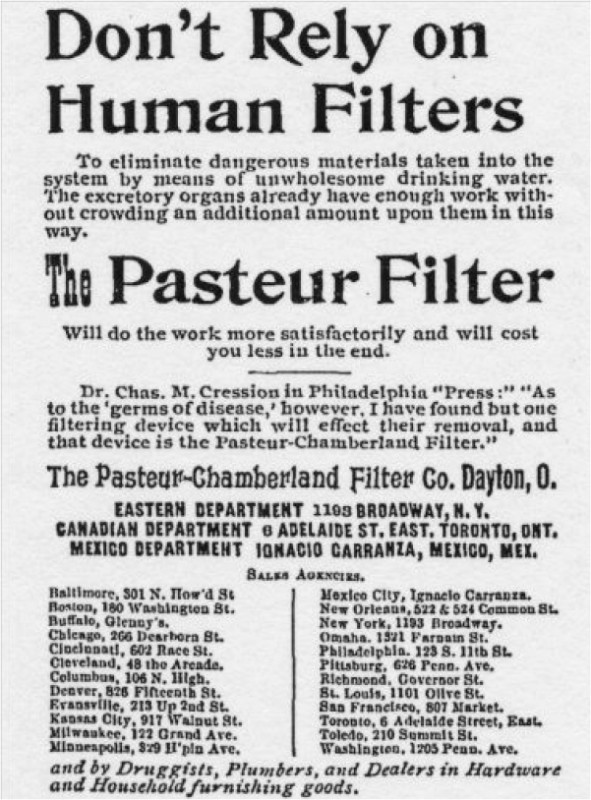

Advertisement, published in Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly 36, no. 2 (August 1893): 133. The ad confirms that the Chamberland filter was being sold in Canada, Mexico, and the United States by early 1893.

During the excavation in Sacramento of a trash pit at the site of the home of Leland Stanford, nineteenth-century railroad magnate and onetime governor of California, sherds of an odd-looking ceramic object were found. One fragment was marked “Filtre Chamberland, Système Pasteur”; there were also marks related to the ceramics maker, identified as Hippolyte Boulenger et Cie of Choisy-le-Roi.

The sherds are from a ceramic filter developed by Charles Chamberland (1851–1908), a physician and biologist who worked at the Pasteur Institute (fig. 1). The institute, created by Louis Pasteur in France in the latter part of the nineteenth century, was at the forefront of medical technology focused on the prevention of a variety of diseases. After proving his theory that illness was caused by microbes, Pasteur’s laboratory was responsible for developing a number of devices to remove germs from drinking water.

In 1884, with the aim of countering the typhoid epidemic then raging in Paris, Chamberland invented a filter that was attached to the end of a porous porcelain cylinder. Called “Filtre Chamberland—Système Pasteur,” this novel device also facilitated the discovery of diphtheria and tetanus toxins. Chamberland’s note on his invention was formally presented to the French Academy of Sciences in 1884.[1] His introductory remarks emphasized the importance of Pasteur’s discovery that most germs were passed via water, not air, and therefore an effective filter to rid drinking water of germs and microbes was a great boon to public hygiene:

The apparatus that I have the honor to present to the Academy adapts itself directly to water taps and functions by way of the pressure in these taps. Under a pressure of approximately two atmospheres, which is the level of pressure at the Pasteur Laboratories, using a single porous cylindrical tube or “filter-candle,” 20 centimeters long by 25 millimeters in diameter, one can obtain 20 liters of clean water a day, which would seem to me to be adequate for the ordinary needs of a household. By multiplying the number of tubes formed into batteries, one could obtain enough purified water to accommodate a school, a hospital, a barracks, etc. The filter makes possible a veritable clean source of water for the household similar to water from a pure spring, devoid of microbes.

The cleaning of this filter is extremely easy. Not only can one brush the exterior surface of the tube that becomes soiled by the suspended materials in the water, but in addition, one can immerse the tube in boiling water and so destroy the microbes that it has filtered out. This re-establishes its original porosity and the tube may thus be used indefinitely.

The filter was designed to be attached directly to a spigot and thus to deliver clean water directly from a tap; its effectiveness could be increased by using multiple filters (fig. 2).

In an article published in Medical News on June 6, 1885, Dr. Alfred Girard touted the Chamberland filter, pointing out the advantages of the filter over boiling as a means of purifying water, and also warning of the need for careful testing of the devices by the manufacturer during fabrication.

The principle of the filter is to force the water through porcelain porous enough to allow the passage of the liquid, but barring that of even the minutest germs. The apparatus consists of one or more porous porcelain cylinders, set in metallic tubes of about two inches diameter, and twelve inches length, which are in communication with the water supply,—the whole being encased in a metallic frame attached to a tap. The water enters the interval between the porcelain and metal tubes, and percolates through the walls of the former, which drain into an outlet pipe. All there is needed is a pressure of at least two atmospheres (a difference of level of about sixty feet). With this each tube will allow the percolation of about a quart an hour, and with the apparatus I examined, and which, probably, is the one intended from practical use, containing six tubes, a daily supply of about 36 gallons of biologically pure water can be obtained.

Regarding defects in the filter, Girard quotes from a letter he received from an eminent European hygienist, Professor E. Vallin:

The Chamberland filter is of great service, but has also defects. It requires great water pressure, at least two atmospheres. . . . It filters slowly, and it is necessary to place under it a glass receptacle, holding 25–50 liters, with a stopcock, to provide always for a good supply. The filtration is thorough, and no proto-organisms even of the smallest kind, can pass, provided the tubes of porcelain have been properly tested, otherwise they may have fissures imperceptible to the eye, but sufficiently large to permit a free flow of water. Sometimes the tubes are faulty, on account of being too porous, so that the microscopic germs can pass through. . . . I told Mr. Chamberland he should not allow any apparatus bearing his name to be sold without their first being tested by the manufacturer. I believe he will watch the manufacturer carefully, for you know that Mr. Chamberland is a very distinguished savant; he is the director of Pasteur’s laboratory, and has been associated with Pasteur in most of his researches on anthrax and hydrophobia; he is Professor of Physics, Doctor of Sciences, and graduated among the first from our Superior Normal School.

In his conclusion Girard announces that he has “drawn the attention of a New York importer to the advantages of the Chamberland filter, and doubtless a number of these filters will soon be brought to this country and exhibited.”[2]

In an article published in 1897, Dr. C. G. Currier singled out typhoid fever as one of the worst aZicting the United States and called for a major effort to be put into protecting the water supply. Currier particularly noted the efficacy of the Pasteur-Chamberland filters, although he also recommended the Berkefeld brand.[3]

Artifact Inscriptions

The markings on the artifact provide a great deal of information (fig. 3). “H. B. & Cie, Choisy-le-Roi” refers to the manufacturer, Hippolyte Boulenger and Company, in Choisy-le-Roi, an industrial suburb of Paris. Hippolyte Boulenger succeeded his uncle Louis Boulenger in 1863 and retained sole proprietorship of the company until 1878, when it was transformed into the Société The. [Hippolyte] Boulenger et Cie, with Hippolyte Boulenger as sole manager until his death in 1892.[4] According to Bernard André, secretary-general of Comité d’Information et de Liaison pour l’Archéologie (CILAC), the company kept the same name even after Boulenger’s death.

The filter is also marked with the letters Bté S.G.D.G. André explained that this stands for “Breveté Sans Garantie du Gouvernement” (Patent without the Guarantee of the Government)—perhaps something like “Patent Pending.”[5]

Whereas the nipple had numerous inscriptions, the bougie had no identifying marks, so once it broke away from the nipple the two objects were not interpreted as being part of one piece—especially because the nipple was of a glazed porcelain and the bougie was of a porous, unglazed ceramic. Fortunately, the detailed image of the full filter as shown in the Wiesnegg catalog made it possible to associate the pieces of the bougie found in the same deposit (fig. 4, top). The portion that would have been attached to the nipple was glued in place (fig. 4, bottom) based on this documentary evidence.

U.S. Distribution

On February 16, 1886, U.S. Letters Patent No. 336,385 was issued to Charles Edward Chamberland “for a filtering compound composed of pipe clay, or other suitable clay, diluted with water, and then mixed with porcelain earth or its equivalent, the latter being first baked and then reduced to a fine powder.”[6] In advertisements for the filter published in 1893, the Pasteur-Chamberland Filter Company, a company based in Dayton, Ohio, claimed to be the “sole licensee for the United States, Canada, and Mexico” (fig. 5).[7] Given the fearsome nature of typhoid and the fact that the filter had been issued a patent in 1886, it is likely that it was on the market in the United States earlier than 1893—perhaps as an import directly from France—but this has not been determined by the author.

Leland Stanford Jr.

The presence of the Chamberland filter at the Sacramento excavation site is intriguing. While on an extended European tour with his family, the Stanfords’ only son, Leland Stanford Jr., contracted typhoid fever and died in Italy in 1884, the same year the filter was patented.[8] Although the Stanfords had left Sacramento when their son was only five years old, ten years before he died, their mansion had been donated to the Sisters of Charity as a home for orphans, so there is a possibility that Mrs. Stanford purchased the filters for the welfare of the children. However, as the cistern was not on Stanford property but on an adjacent parcel, this is somewhat unlikely. Whatever the actual course of events, the discovery of these unusual artifacts—to my knowledge unreported in other historic sites in the United States—at this site is remarkably coincidental and poignant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank archaeologist Richard Hastings and his assistant, Daniel Barr, for bringing to my attention these artifacts from the Stanford House excavations. My thanks also go to Peter Schulz, Senior State Park Archaeologist, for his assistance with references concerning medical technology of the late nineteenth century. Special appreciation is directed to Bernard André, secretary-general of CILAC, for his assistance in translating the various abbreviated acronyms used on the filter, and also to Annick Perrot, Conservator, Pasteur Institute Museum, Paris, for providing images of the Chamberland filters.

Glenn J. Farris, Research Associate, University of California, Berkeley;

farris@dcn.org

The paper was presented by the academy’s president, Henri Bouley, on Chamberland’s behalf. Henri Bouley, “Chimie physiologique—Sur un filter donant de l’eau physiologiquement pure,” Comptes Rendus des Sciences de l’Académie des Sciences 33 (1884): 247–48.

Alfred C. Girard, “The Chamberland Filter,” Medical News 46 (June 6, 1885): 24.

C. G. Currier, “Water Purification Hygienically Considered,” Medical News 71 (November 6, 1897): 19.

Hélène Bougie, “La Faïencerie de Choisy-le-Roi (Société Hippolyte Boulenger et Cie) à la fin du XIXe siècle,” Archéologie Industrielle en France 10 (1984): 1–15.

Bernard André, personal communication with author, 2006.

“Decisions Relating to Patents,” Scientific American 68 (March 25, 1893): 12.

Advertisement, Frank Leslie’s Popular Monthly 36, no. 2 (August 1893): 133.

Archaeologists may find it of interest that during the visit to Turkey, Leland Jr. was given a personal tour of the excavations of Troy by its excavator, Heinrich Schliemann, who had very possibly been acquainted with Leland Stanford Sr. when they were both merchants in gold-rush Sacramento in the early 1850s. Theresa Johnston, “About a Boy,” Stanford Magazine (July–August 2003), www.stanfordalumni.org/news/magazine/2003/julaug/features/junior.html (accessed March 23, 2008).