Pitcher, possibly Medford, Massachusetts, ca. 1840. Earthenware. H. 13". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This slip cast pitcher is one of four known. Two are impressed on the base with “MEDFORD” suggesting Medford, Massachusetts, as their place of manufacture. Nothing is known about the modeling of the original or the subsequent production of the molds. All of these jugs have a characteristic buff earthenware body with a thick Albany slip glaze that varies from shades of dark brown to almost black. The illusion of teeth is the result of scraping away the Albany slip to expose the buff color of the clay body.

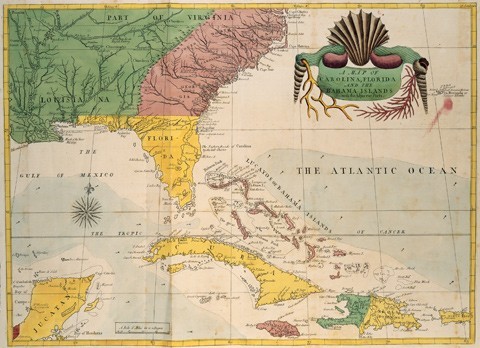

Mark Catesby, Map of Carolina, Florida, and Bahama Islands with the Adjacent Parts, London, 1754. (Private collection.)

Detail of the map illustrated in fig. 2 showing the island of Hispanola. Its aboriginal inhabitants originally knew the island as Haiti. The Spanish changed the name to Santo Domingo, and in 1697 the formal division of the island into Santo Domingo and Saint-Domingue took place. In 1804, Saint-Domingue ceased to exist and was renamed using the early term Haiti.

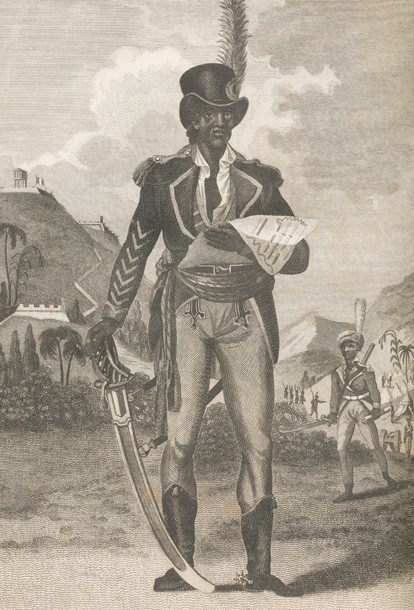

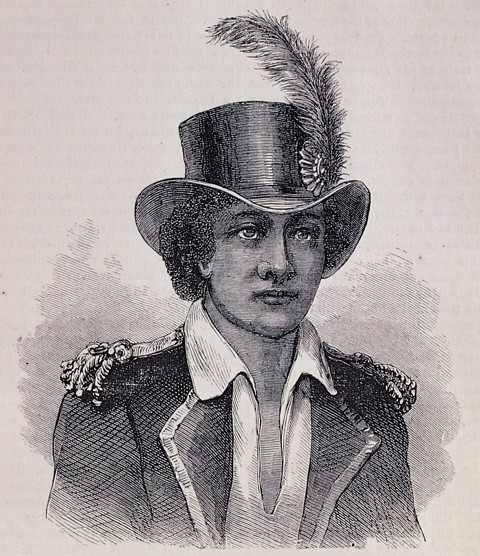

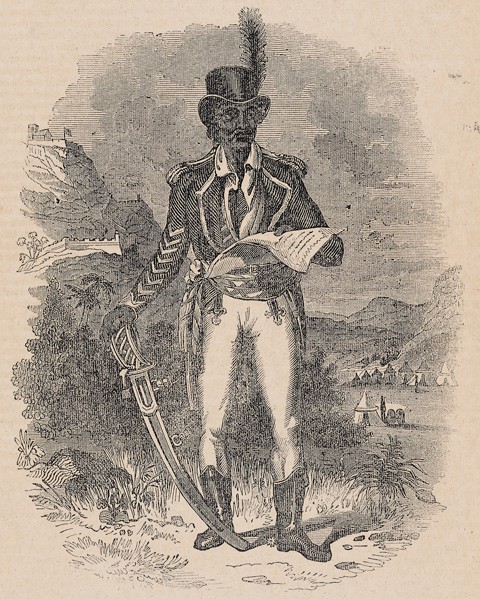

Marcus Rainsford, Toussaint L’Ouverture, London, 1805. (Courtesy, Archives & Special Collections, University of Miami Library.) This is the earliest known image of Toussaint L’Ouverture taken from sketches made by Marcus Rainsford. It appeared as an illustration in Rainsford’s An Historical Account Of The Black Empire Of Hayti: Comprehending A View Of The Principal Transactions In The Revolution Of Saint Domingo; With Its Ancient And Modern State. Toussaint is represented as a dignified military leader with a sword in one hand and a battle map in the other.

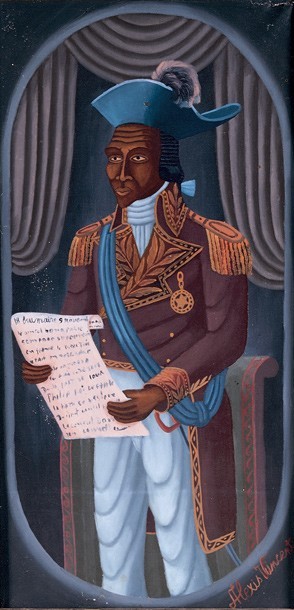

Alexis Vincent, Toussaint L’Ouverture, Haiti, ca. 1970. Oil on canvas. (Private collection.) The image of Toussaint is commonly evoked by contemporary Haitian folk painters. Vincent’s painting is reflective of the twentieth-century self-taught Haitian artists who began to make their contribution to Haitian life and cultural expression in the 1940s and 1950s. In this painting, Toussaint is depicted in a similar pose to the Marcus Rainsford engraving except that a commemorative scroll or proclamation has taken the place of the map.

Detail of the impressed “medford” stamp on the base of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 8. (Private collection; photo, Jay Lewis.)

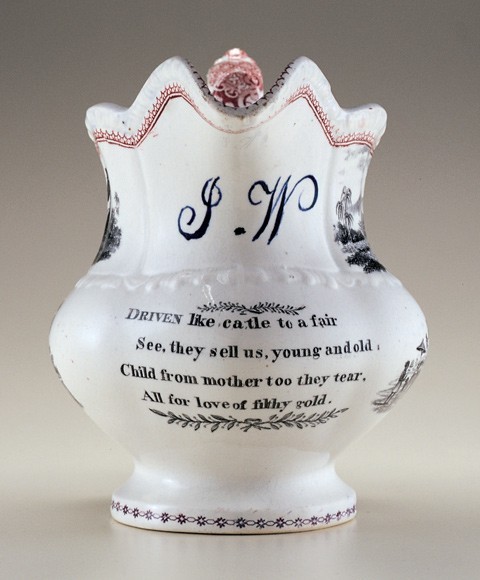

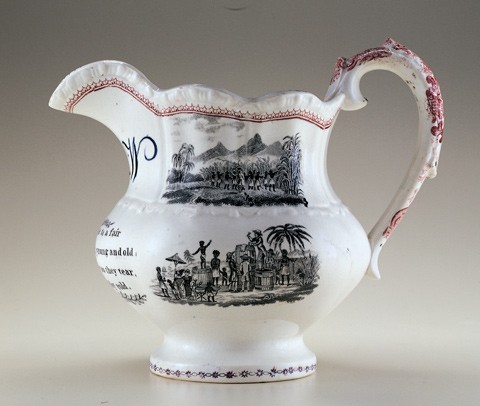

Pitcher, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1840. Earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Inscribed with the initials “J.W.” and the verse “DRIVEN like cattle to a fair; See they sell us, young and old. Child from mother too they tear, All for love of filthy gold.” This rare transfer-printed jug made for the abolitionist market contains graphic scenes of slavery in the West Indies. Note the general overall shape, handle, and rim characteristic of ca. 1840 classical or Greek Revival styles in English and American pottery and porcelain.

Pitcher, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1840. Earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Inscribed with the initials “J.W.” and the verse “DRIVEN like cattle to a fair; See they sell us, young and old. Child from mother too they tear, All for love of filthy gold.” This rare transfer-printed jug made for the abolitionist market contains graphic scenes of slavery in the West Indies. Note the general overall shape, handle, and rim characteristic of ca. 1840 classical or Greek Revival styles in English and American pottery and porcelain.

Pitcher, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1840. Earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Inscribed with the initials “J.W.” and the verse “DRIVEN like cattle to a fair; See they sell us, young and old. Child from mother too they tear, All for love of filthy gold.” This rare transfer-printed jug made for the abolitionist market contains graphic scenes of slavery in the West Indies. Note the general overall shape, handle, and rim characteristic of ca. 1840 classical or Greek Revival styles in English and American pottery and porcelain.

Pitcher, possibly Medford, Massachusetts, ca. 1840. Earthenware. H. 13". (Private collection; photo, Jay Lewis.) This example of the Toussaint L’Ouverture pitcher has an extremely dark brown, almost black, Albany slip. The outline of the eyes have been highlighted by scratching through the slip suggesting that although these pitchers were made from the same model, they could be individualized by the potter.

Detail of the unmarked base from pitcher illustrated in fig. 1. The fingerprints of the potter who dipped the pitcher in Albany slip have been recorded on its base.

Side view of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 1. (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

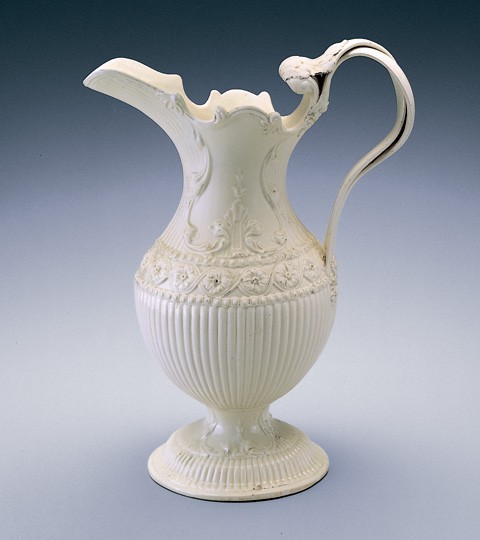

Ewer, Leeds, ca. 1790. England. Creamware. H. 11 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This late eighteenth-century ewer, inspired by antique Greek and Roman examples, exhibits molded frieze-like elements on the neck and body similar to the grammar of the design elements representing the military cap on the L’Ouverture pitcher.

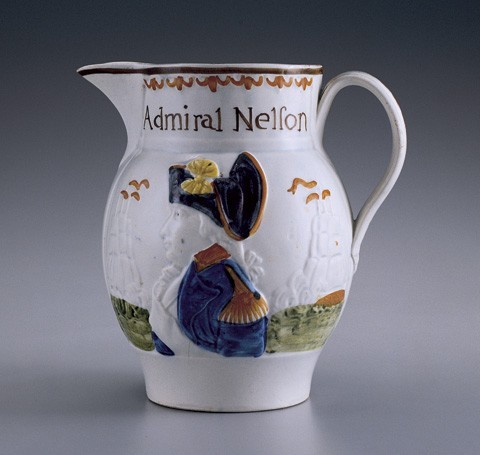

Jug, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1805. Pearlware. H. 6 1/8". (Chipstone Foundation, Noël Hume Collection.) Drinking jugs and pitchers have been made to commemorate cultural heroes and promote political messages since antiquity. In the late eighteenth century, with the rise of the Staffordshire potteries, large quantities of molded commemorative wares were made for middle-class consumers in the Anglo-American market.

Pitcher, possibly Medford, Massachusetts, ca. 1840. Earthenware. H. 13". (Courtesy, Arthur Goldberg.) Also marked “MEDFORD,” this pitcher has the illusion of teeth like the example shown in fig. 1.

Rear view of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 13. (Courtesy, Arthur Goldberg.)

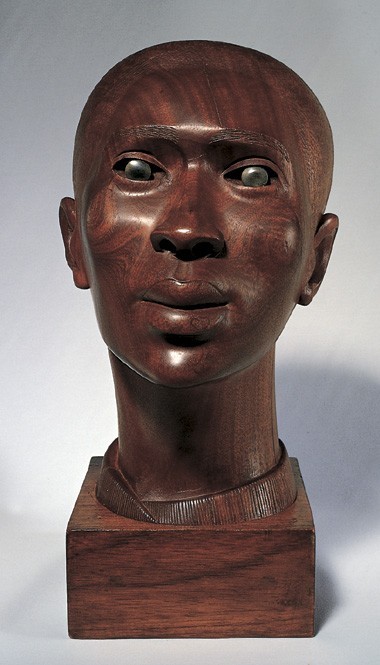

Elizabeth Catlett, Negro Woman, ca. 1956. Wood and onyx. H. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Clark Atlanta University Art Galleries ©.)

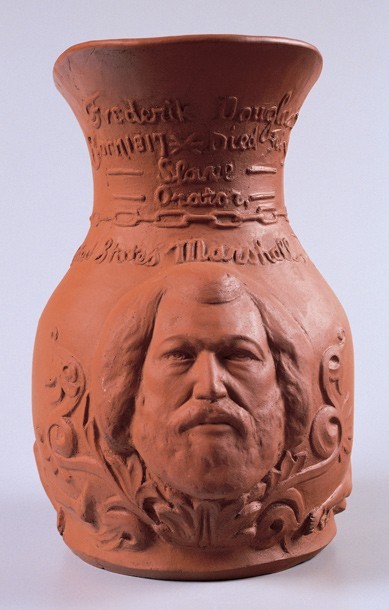

Pitcher designed and copyrighted by J. E. Bruce, Albany, New York, 1896. Unglazed red earthenware. H. 10 1/4". (Courtesy, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Although not directly related to the Toussaint L’Ouverture pitcher, this object attests to the use of ceramics vessels as the means for conveying important historical and political concerns. Hand modeled and molded, the pitcher bears the inscription: “Frederick Douglass/Born 1817/Died Feby 20 1895/Slave Orator/ United States Marshall, Recorder of Deeds D.C./Diplomat.”

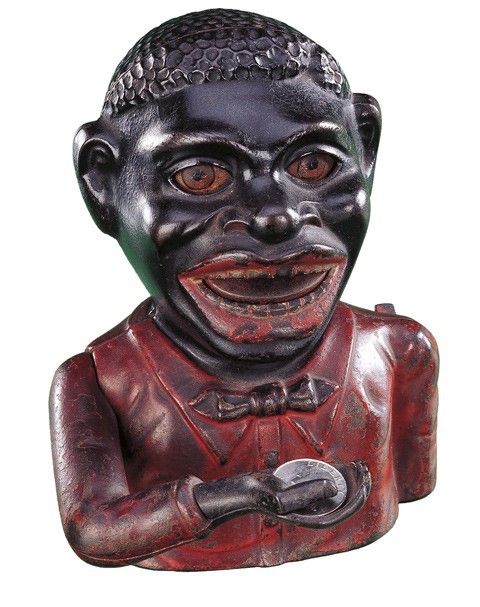

Jolly Nigger Mechanical Bank, J. & E. Stevens Co., Cromwell, Connecticut, patented March 14, 1892. Cast iron. H. 6". (Courtesy, Larry Vincent Buster, The Art and History of Black Memorabilia [New York; C. Potter, 2000]; photo, Kenneth Paul, Sr.)

Face jug, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1860. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 6". (Private collection.

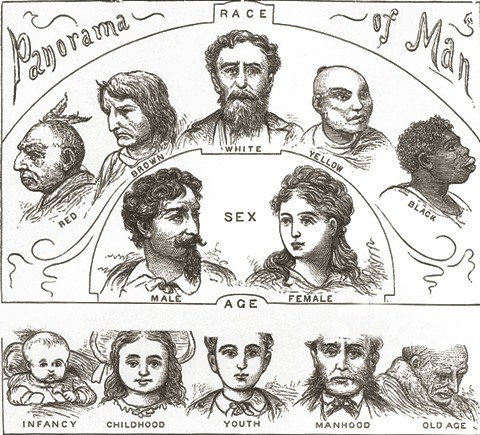

by Nelson Sizer and H. S. Drayton, A.M., M.D., Heads and Faces and How to Study Them (New York: Fowler & Wells Co., 1891.) (Chipstone Foundation.

Eugenie Lebrum, Toussaint L’Ouverture, General en chef à St. Domingue, Paris, 1825. (Private collection.) This image of Toussaint appears as the frontispiece in a history of Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition in Haiti.

Toussaint L’Ouverture from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 43, no. 253 (1871). (Private collection.) In contrast to the image portrayed in the 1838 Penny Magazine, this image, also after the Rainsford engraving, shows a young, almost boyish, Toussaint.

Engraving from The Penny Magazine, (London: Published by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, 1838). (Private collection.) This depiction of Toussaint L’Ouverture appeared on the cover of Penny Magazine in 1838. The magazine contained a wide range of informative illustrated articles and was aimed at the working class. The 1805 Rainsford engraving is the obvious source of this image although Toussaint’s facial features have been given a much harsher look.

Nicolas Eustache Maurin, Toussaint L’Ouverture, from Iconographie des Contemporains, Paris, 1832. Lithograph. (Courtesy, Print & Picture Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia.) With its “ape-like” profile, this was the most frequently reproduced image of Toussaint during the period in which the portrait pitcher was modeled.

Engraving of Harriet Martineau, 1802–1876. (Chipstone Foundation.)

Jacob Lawrence, The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture, No. 21: General Toussaint L’Ouverture attacked the English at Artibonite and there captured two towns, New York, 1938. Tempera on paper, 11 1/2" x 19". (Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans. Aaron Douglas Collection. Artwork © Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, courtesy of the Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation.)

Jacob Lawrence, The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture, No. 20: General Toussaint L’Ouverture, Statesman and military genius, esteemed by the Spaniards, feared by the English, dreaded by the French, hated by the planters and reverenced by the Blacks, New York, 1938. Tempera on paper, 19" x 11 1/2". (Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans. Aaron Douglas Collection. Artwork © Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, courtesy of the Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation.) Toussaint L ‘Ouverture was the first of Lawrence’s many major series. Researched and created from 1937–1938, and completed when he was only twenty-one, the paintings thrust Lawrence onto the national art scene.

Brothers and Friends: I am Toussaint L’Ouverture. My name is perhaps known to you. I have undertaken to avenge you. I want liberty and equality to reign throughout St. Domingue. I am working towards that end. Come and join me, brothers, and combat by our side for the same cause.—Proclamation of August 29, 1793

The traditional curatorial approach to ceramic analysis prioritizes the identification of quantitative data: ware and glaze type, date of manufacture, place of origin, artistic style, subject, and authorship. These descriptive categories offer the typological stability upon which a neat ordering of the past can be constructed. But many artifacts, as well as the cultural contexts from which they emerge, are not so easily defined. In search of a more complex understanding of ceramic artifacts, many scholars have come to utilize different methodologies, including archaeology, anthropology, and material culture, which offer more intuitive understandings of the meanings, needs, and beliefs of the makers and original users. Although none of these analytical approaches can claim interpretive authority, they can be usefully combined. This essay merges a variety of strategies to help decipher a newly discovered group of mid-nineteenth century portrait pitchers which depict the famed Haitian leader Toussaint L’Ouverture and which symbolize the complexity of attitudes about race in American history (see fig. 1).[1]

Historian George F. Tyson, Jr. describes Toussaint, a former slave who led the first successful slave revolt in the Americas, as a mutable historical figure whose precise legacy is “obstructed by the fact that he has been all things to all men, from blood thirsty black savage to the greatest black man in history.”[2] The portrait pitchers themselves similarly defy conventional understanding. Instead, they function as complex symbols that remain as potent today as at the time of their creation. To modern observers, the design is not only visually powerful but also offensive, distinguished by overtly racialized features that challenge contemporary sensibilities about appropriate representation and artistic license—reactions that are a significant part of coming to terms with this evocative object but necessarily shaped by our own historical context. A more thorough interpretation of this piece must also consider earlier historical contexts and, in particular, the racial ideologies that informed them.

When these pitchers were made in the 1840s, ideas about race were influenced by issues far more complex than the slavery debate; even the most vocal abolitionist sympathizers held diverse and ambivalent attitudes. Americans and European colonists in the Caribbean islands (figs. 2, 3) alike relied on complex and formulaic categories that could, for example, denote specific racial and legal identities of people down to 15/16th white or black. Another compelling challenge in reading this pitcher is Toussaint L’Ouverture’s intricate and even contradictory historical legacy—he has variously been remembered as either a heroic nation builder or as a complacent conspirator who did not effectively promote the cause of freedom (figs. 4, 5). The portrait on these pitchers similarly is hard to decipher. Although possibly meant to be an anti-slavery sympathizer’s ennobling depiction of an important historical figure, the image clearly is associated with a derogatory engraved image created in 1837.

A logical starting point for interpreting the pitchers’ meaning is to consider the strongest piece of objective evidence: the stamped mark “Medford” found on the underside of two of the four pieces (fig. 6). The stamp almost certainly suggests manufacture in Medford, Massachusetts, a town on the Mystic River just north of Cambridge. Recent research by Electa Kane Tritsch reveals that Medford’s abundant sources of local clay allowed it to become a major brick-making center during the middle and later part of the nineteenth century. The adjacent towns of Charlestown and Somerville also supported brick-making operations and several well known ceramic manufactories. In the mid-eighteenth century, Medford may have had a pottery business of its own that was run by the Tufts family, but nothing is known of their production. That potting occurred in the mid-nineteenth century is documented by a small group of simpler earthenware pieces that similarly are marked “medford.”[3]

The production of the Toussaint pitchers in Medford also relates to the emergence of eastern Massachusetts as a leading center of abolitionist activity. The region was home to William Lloyd Garrison, Lydia Maria Child, and Wendell Phillips, and several of the most influential abolitionist publications, including Garrison’s The Liberator, the National Philanthropist, and the Massachusetts Abolitionist, were produced in Boston. Also leading the way were organizations such as the Massachusetts Emancipation Society and the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society (later the Massachusetts Female Emancipation Society). In addition to promoting abolitionist ideology through the support of lectures and publications, the women’s groups sponsored fairs that sold a wide range of art works, craft goods, and manufactured items to raise funds. A newspaper advertisement for a fair in 1840 notes that in addition to drawings, expensive cloth and clothes, and autographs by well known abolitionists, attendees could buy “elegant anti-slavery china, made for the occasion.” Perhaps the Toussaint pitchers specifically were produced for this type of abolitionist fund raising event (fig. 7).[4]

One tantalizing, but currently unsustainable, attribution suggests that the pitchers were made in the Medford pottery that was opened circa 1838 by brothers John and Thomas Sables and their partner Job Clapp. That year all three men were listed as “all of Medford, Potters” on legal documents for their purchase of a group of former distillery buildings, which then became home to their pottery. Subsequent property sales over the next few years describe one or more of the men as “potters.” In 1841 Thomas Sables, described as a potter, sold the “land, wharf, dwelling house, pottery and other buildings” to a Maine ship captain, a transaction that apparently marked the end of the Sables and Clapp pottery. The short life of the Sables and Clapp partnership probably reflects the men’s diverse craft skills. In records both before and after the potting years, the three variously were recorded as housewrights, carpenters, and shipwrights—woodworking trades that, in theory, would have made the Sables and Clapp better suited to the production of slip-cast pottery than to wheel- or machine-turned work. One other intriguing clue is the Sables’ unusual last name, which suggests that they may have been African-American. Nineteenth-century writers and lecturers used the word “sable” as a synonym for “black.” An example of this usage is the British evangelist James Stephen’s 1804 distinction between the “sable heroes of Haiti” and the “debased slaves” in other British colonies. [5]

A close look at the pitchers’ formal elements suggests a number of additional facts about their origin, meaning, and function. All four are slip-cast earthenware, apparently formed in the same mold. There are minor variances in the manufacture of the pots, but nothing that would suggest production in different potteries. All are covered with a layer of lustrous Albany slip that ranges from a rich chocolate brown to near-black, colors which seem to have been deliberately chosen to suggest the skin tone of a person of African descent. The potter’s close attention to the coloristic effects of the materials is evidenced by areas in which the glaze deliberately has been removed to reveal the off-white color of the body. Such sgraffito marks delineate the eyes on one example (fig. 8), and on another pitcher (see fig. 1) an unglazed patch was left in the mouth, perhaps indicating white teeth. The sculpting of the back and upper portion is much more flat and schematic than the sophisticated rendering of the face. That the pitchers were made to be functional as well as sculptural is indicated by the fact that they are glazed inside and out. Their pronounced baluster shapes likewise duplicate the form of more conventional ceramic water pitchers.

The front corner of the military hat conveniently serves as a spout, while the handle awkwardly protrudes from the back of the head. Among the curious inconsistencies on the pitchers is the design of the hat. Because of the fragility of the clay, the plume that would normally protrude upward from the front of a genuine tricorner hat instead surreally turns downward. Also, in order to provide additional stability to the pitchers, the maker pinched out the clay at the bottom to form a continuous foot—a fleshy protrusion that creates the uncomfortable feeling that the man has been decapitated. The casting line that vertically encircles the vessel, bisecting the face, could have easily been smoothed out but instead was left intact—evidence, perhaps, of large-scale production by relatively unskilled workers. Finally, the pitcher illustrated in figure 1 has four smudgy slip marks on the base that poignantly preserve the fingerprints of the potter and suggest a speed of manufacture that is difficult to reconcile with the object’s sophisticated modeling (fig. 9). All of these inconsistencies suggest a collaboration between a skilled sculptor and a production-oriented potter.

Despite its unusual form, the overall design has much in common with the artistic conventions of classicism. The artist’s fluency in the language of ancient ornamentation is evidenced by the geometric arrangement of stylized foliage along the top edge of the hat, which emulates the much more intricately decorated gold-thread trim tapes used on cloth military hats of this sort. When the pitcher is viewed from the side, the horizontally delineated lines of the hat create an unmistakably frieze-like passage, consistent with the classically inspired decoration of many late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century pitchers (figs. 10, 11). Unlike other ceramic portrait pitchers made in this era, however, the careful rendering of the man’s face mirrors the individuation and formal bearing associated with classical sculpture (fig. 12).

Many of the facial details are fashioned with an apparent sensitivity to psychology, including subtle furrows that are cut into the forehead. The eyes shift slightly to one side, as if in expectation, and the mouth is parted, as though the man were on the brink of speech. Cords of muscle are carved into the neck, giving an impression of physical power (figs. 13, 14).

Other features—notably the wildly exaggerated brow, nose, and lips, along with the incised whorled lines that form the hair—are not in keeping with the Touissant pitcher’s more classical elements. When compared to the 1956 sculpture, Negro Woman, made by African-American artist Elizabeth Catlett (fig. 15), the pitcher’s overwrought facial elements appear not only racialized—meant to depict, as objectively as possible, racial identity—but also racist—meant to indicate racial inferiority. Discerning the precise meaning of these elements in the context of nineteenth-century material culture remains difficult. Although a number of commemorative wares were produced (fig. 16), a search for visual comparisons immediately brings to mind the type of artifacts known among collectors as “black memorabilia” (fig. 17). In its portrait of a full head, the design of the Toussaint pitcher also recalls southern face jugs, which were made by both black and white potters and often gruesomely depict African-American faces (fig. 18). When the Medford pitchers were potted, however, manufacture of black memorabilia and face jugs had only just begun. Far more common at the time were images of African-Americans in print media, which often showed viscously stylized imagery. Motivated by racist assumptions, such depictions also reflected an emerging belief among whites in the pseudoscience of phrenology, with its obsessive grouping of physiological and racial archetypes (fig. 19). Phrenologists argued that Africans occupied the lowest position in the hierarchy of races. This assertion was defended by emphasizing such supposedly African characteristics as large lips, wide noses, and most tellingly, a jutting lower brow—a feature that implied a connection to simian physiology and introduced into popular vocabulary the term “lowbrow.”[6]

The facial features on the Medford pitchers may be more accurately contextualized by establishing the specific identity of the subject as Toussaint L’Ouverture. To begin with, only a small number of black military figures might have been commemorated on a mid-nineteenth-century American artifact. Among the potential candidates is Crispus Attucks, the fugitive slave who in 1770 was the first American to die in the Boston Massacre. Thereafter he was hailed as a symbolic leader of the patriot cause and reemerged as a key historical figure in the rhetoric of abolitionists. However, Attucks was a sailor in Boston, not a soldier, and existing historical depictions do not show him wearing a military uniform or hat, so he seems an unlikely candidate. Another possibility is that the pitchers portray one of the small number of black troops who fought in the Revolutionary War. A Haitian regiment that battled alongside the colonists in Georgia, for example, included many subsequent leaders of the Haitian slave revolts. On the other hand, the majority of African-Americans in the Revolutionary War fought for the British and Loyalists.

In 1775 Lord Dunmore, the last Royal Governor in Virginia, offered freedom to slaves who would fight for the British, a strategy that ultimately failed but that aroused the fear of many Virginians. The manumitted slave soldiers wore uniforms that were adorned with badges inscribed “Liberty to Slaves.” But their story was not widely referenced by abolitionist writers and lecturers, so they too remain improbable candidates as the subject of the Medford pitchers. Haiti, on the other hand—along with the men who led its revolution at the end of the eighteenth century—occupied a prominent symbolic place in nineteenth-century American culture and remained at the center of debate among abolitionists and pro-slavery apologists alike. The most intriguing figure in the story of the Haitian revolution was Toussaint, who was, as Tyson suggests, “the very personification of its ideals and contradictions,” an inspired yet messianic military and political genius who “molded the revolutionary army of slaves into an efficient, disciplined fighting unit; who defended the revolution by an astute mixture of statecraft and diplomacy; who restored economic stability to his ravaged country; who, through his personal achievements, inspired in his people, and in black people everywhere, a renewed sense of pride and purpose.” For nineteenth-century Americans, Toussaint became the embodiment of the Haitian revolution and the various issues it brought to the forefront.[7]

A survey of the few surviving images of Toussaint not only supports the conclusion that he is the subject of the Medford pitchers but also offers some clues regarding the figures’ exaggerated features. Although no life portraits of the former slave are known, several widely distributed engraved depictions were created from written descriptions offered by Haitian, British, French, and American contemporaries, descriptions that often are not complimentary (figs. 20-22). Among these are the comments of abolitionist Victor Schoelcher, who noted Toussaint’s “repulsive ugliness and poor build.”[8] Other commentators likewise drew on the language of phrenology and frequently remarked on his pronounced, jutting jaw.

The most likely visual source for the design of the Toussaint pitchers is a lithograph created by French artist Nicolas Eustache Maurin for an 1832 portrait volume titled Iconographie des Contemporains (fig. 23). Maurin’s portrait likewise was intended as an explicitly antagonistic caricature, accounting for what art historian Hugh Honour calls its “deformed, almost simian profile.”[9] With an illegible signature added underneath the image to give it an air of authenticity, the lithograph became the most widely reproduced image of Toussaint. The modeling of the face on the Maurin engraving is comparable to that on the pitchers, as is the proportioning of the facial and decorative elements, including the hat and the parted lips. Additional shared elements include the protruding sidelong eyes, which correspond to period descriptions.

The early French biographer, Louis Dubroca, remarked on Toussaint’s “dark and taciturn” disposition and his “rapid and penetrating” glances. Another early description refers to a relatively small man who lost his upper front teeth in battle, which may partially explain the large underbite shown in the engraving. Maurin’s characterization of Toussaint is also specifically linked to its production for a French audience.[10] More than any other Haitian leader, Toussaint and his followers supported the French colonial authorities through the revolution only to sever ties very late in the conflict. Humiliated not only by losing their most profitable colonial outpost but also by losing it to a native army led by an ex-slave, French leaders such as Napoleon Bonaparte portrayed Toussaint as a villainous traitor whose rise to power was only made possible by French support. The Maurin portrait drew on these attitudes to create a racist image of a diminished historical figure.[11]

The available evidence makes it possible to conclude with some certainty that the pitchers were based on the Maurin portrait of Toussaint and were likely made for the abolitionist market in eastern Massachusetts. But other, ultimately more important, interpretive questions remain, particularly in regard to the Haitian subject matter and its potential meanings. In general, American interest in Haiti was linked to the fascinating details of the revolution itself, a mind-boggling series of cross-cultural and cross-racial revolts, alliances, and betrayals involving French, British, and Spanish colonizers and military leaders, and, of course, Haitians of every racial and social strain. African-Americans and abolitionist sympathizers could find much about the revolution that was inspiring. As historian Eugene Genovese notes, “as late as 1840 slaves in South Carolina were interpreting news from Haiti as a harbinger of their own liberation.”[12] On the other hand, white Americans—especially those in the South—found much to fear in the occurrence of racial instability so close to home and in Toussaint’s spectacular rise from slave to self-proclaimed “Life Governor” of the whole island of Hispaniola. To some, the Haitian revolution served as a potent symbolic reminder of the evils of slavery, but to most white Americans, the event functioned as a frightening reminder of the potentially violent consequences of slave revolt. In 1855 abolitionist William Wells Brown wrote, “Let the slave-holders in our Southern States tremble when they call to mind these events...that day is not distant when the revolutions of St. Domingo will be reenacted in South Carolina and Louisiana.”[13]

Though much of the historical credit for the slave revolution should be shared by other influential leaders, such as Henri Christophe and Jean-Jacques Dessalines, Toussaint was the Haitian leader Americans—white and black, pro- and anti-slavery—came to know and in many cases to fear. He was widely embraced as a contradictory symbol of both the liberating and the destructive potential of slave revolt. According to nineteenth-century historian James Brewer Stewart, abolitionists hoped that “every plantation had its own Toussaint.”[14] But other Americans remained fearful of the prospect of what was frequently portrayed as a racially-motivated bloodbath. Such fears were only fueled by the vehement rhetoric of southern pro-slavery ideologues, who in the aftermath of the Denmark Vesey and Nat Turner uprisings used the specter of revolt as an excuse for justifying increasingly brutal laws regulating slavery. In 1829 abolitionist David Walker published his widely distributed Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World, which encouraged other African-Americans to read “the history particularly of Hayti, and see how they were butchered by the whites, and do you take warning.”[15] Throughout the nineteenth century, cultural discourse surrounding the Haitian revolution centered on the possibility of a “race war,” as abolitionists and pro-slavery apologists alike adopted increasingly militant rhetoric. The Toussaint pitchers may have functioned in a similar way, as symbols of both the promise and the threat posed by the Haitian revolution.[16]

For abolitionists in the 1840s, Haiti not only was the site of a watershed event in the fight against slavery but also a nation whose story could be used for their own strategic ends. Historian David Geggus notes that in the early nineteenth century “Haiti became both a political issue in itself and crucial test for ideas about race and about the future of colonial slavery.”[17] In 1842 the Massachusetts chapter of the Anti-Slavery Society sent leading abolitionists Maria Weston Chapman and her husband Henry Grafton Chapman to Haiti in the hopes of Wnding confirmation for the principle of black freedom. The pair returned with ebullient news regarding the Haitians’ “intelligent acquaintance with the character of the anti-slavery men and measures of the United States.”[18]One reason that the Chapmans may have visited Haiti was to evaluate it as a potential home for emancipated slaves. By the 1840s, the so-called “colonization” scheme had become an important, if controversial, part of the abolitionist crusade. Those favoring colonization argued that the slaves should be freed and “returned” to Africa despite the fact that by the mid-nineteenth century the vast majority were American-born. Though the colonization idea was initially promoted by African American activists, many whites soon embraced it enthusiastically.

The primary engine of the new movement was the American Colonization Society, dedicated to relocating the slaves to the African colony of Liberia. The organization achieved some success, providing for the transportation of over 15,000 African-Americans to Liberia over the course of the nineteenth century, with peaks in emigration during the 1840s and 1860s. But the Society had powerful opponents. William Lloyd Garrison, publisher of The Liberator, was a sworn enemy of the “colonizationalists,” a group he blamed for diluting the anti-slavery message. Writing that the Society “rivets a thousand fetters where it breaks one,” Garrision exposed the latent racism of the colonization movement, which tacitly held that America was better off without its black population.[19]

The plan to relocate people to Liberia also had logistical problems, and many adherents of the colonization movement thought that the proximity of Haiti might make it a better site for settlement. In an 1818 address in Philadelphia to the American Convention for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and Improving the Condition of the African Race, Prince Saunders boldly declared that a return to the “paradise of the New World” was in “the best interests of the descendants of Africa.”[20] Mid nineteenth-century Haitian leaders also generally welcomed the idea in hopes of rebuilding their war-decimated population and reviving some semblance of the nation’s former economic stability and diplomatic connections, which effectively ended after the formation of a native government in 1804. King Henri Christophe even offered to defray the costs of transportation because he hoped that the colonization effort would help revive the country’s trade-based economy on far more equitable terms than previously offered by the Spanish and French colonial authorities.[21] Although American fears about the island’s unstable government ultimately discouraged the effort, the fantasy of Haitian colonization was never far from the center of abolitionist discourse—as late as 1863, President Lincoln signed a contract providing for an expatriate colony at Ile á Vache in Haiti, but the attempt proved disastrous due to the corruption of the white leaders of the project.[22]

In short, abolitionists viewed Haiti through a variety of rhetorical and political perspectives that were intended to serve a number of different ends. Abolitionist novels and histories similarly used Toussaint and his country as symbols intended to serve various political and personal agendas. Especially notable is the fictional biography, The Hour and the Man, published in 1843 by English novelist Harriet Martineau (fig. 24). Introduced to his story by Maria Weston Chapman, Martineau recorded her laudable, albeit self-serving, motivations for writing the book: “it flashed across me that my subject must be the Haytian revolution, and Toussaint my hero. Was ever any subject more splendid or fit than this for me and my purposes?” The book, she continued, “will prove my first great work of fiction. It admits of romance, it furnishes me with a story, it will do a world of good to the slave question, it is heroic in its character, and it leaves me English domestic life for a change hereafter.”[23] Other abolitionists, such as Wendell Phillips, were less interested in using Toussaint’s legacy for personal gain than they were in using it to further their cause. In the 1850s, Phillips began lecturing widely on Toussaint and his accomplishments. He extolled Toussaint’s military genius—which in the eyes of detractors was evidence of his “bloodthirsty,” megalomaniacal ways—as proof of the intellectual capacity of the black race. To allay fears about white massacre by freed slaves, Phillips emphasized Toussaint’s kind treatment of white land owners in Haiti. Phillips, like Martineau and other abolitionist thinkers, played an important role in furthering Toussaint’s role as an iconographic figure who could be understood in a variety of ways.[24]

Ultimately, the Toussaint pitchers are as difficult to decipher as the diverse literary and historical depictions of the man and his world. Perhaps they are best understood in light of the famous series of the Haitian leader by artist Jacob Lawrence, painted in the late 1930s.[25] In this cycle of forty-one oil paintings, Lawrence depicts Toussaint in a variety of celebratory ways: as a daring warrior, riding into combat with sword drawn; as a studious intellectual; as a pathetic victim; and, in an image likely based on the 1832 Maurin lithograph, as a commanding general (figs. 25, 26). Lawrence never gives Toussaint definite facial features. Instead, he is a subject on whom viewers can project their own ideas about race and heroism, and the same is true for the Toussaint pitchers. The indeterminacy of Lawrence’s depictions strikes at the heart of the historical legacy of Toussaint. The mid nineteenth-century American orator and colonization advocate James Theodore Holly declared that at the time of the Haitian revolution Toussaint was “the very man for the hour.”[26] Ever since he has continued to fulfill this prophecy. The Toussaint pitchers symbolize the complexity of race in mid-nineteenth century America and, in a very visceral way, arouse the sensitivity of modern viewers to America’s legacy of slavery and racism. On one level, the pitchers embody the racist and stereotypical attitudes that allowed for the institution of slavery in America and the lingering subjugation of African-Americans ever since. On another, they can be read as an abolitionist’s attempt at a more ennobling depiction of a historical figure widely admired by anti-slavery activists in Medford and elsewhere. In fact, the Toussaint pitchers embody both of these contradictory meanings—and until better evidence emerges, they will mirror the historical legacy of the great revolutionary himself and remain all things to all people.

The following—one of the more concise and understandable descriptions of the geographic names used to describe the lands that comprised the island now made up of Haiti and the Dominican Republic—appears in Rayford W. Logan, Haiti and The Dominican Republic (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968), p. 3: “Precise terminology will clarify much confusion about the island on which Haiti and the Dominican Republic are situated. The aboriginal Indians called it Quisqueya or Hayti, The Land of the Mountains. Columbus named it Española, later Anglicized to Hispaniola. Nomenclature became particularly confusing after Spain ceded the western part of the island to France in 1697. In this book, except in quotations, ‘Hispaniola’ means the whole island until 1697, ‘Santo Domingo’ means the Spanish colony before and after partition, and the Dominican Republic, the independent nation. Saint Domingue is the French colony from 1697 to 1804, and Haiti the independent nation.” In an effort to bring clarity to this essay, which considers both pre-Revolutionary Saint Domingue and its post-Revolutionary incarnation as Haiti, the latter designation, which is more familiar to contemporary readers, will be used exclusively

George F. Tyson, Jr., Toussaint L’Ouverture (Englewood CliVs, N. J.: Prentice Hall, 1973), pp. 2–3.

Thanks to Electa Kane Tritsch for her considerable research into Boston-area abolitionist history, associated publications and advertisements, and records of ceramic production in Medford. For mention of Medford brick manufactories, see John Hayward, A Gazeteer of Massachusetts (Boston: John Hayward, 1846); James M. Usher, History of the Town of Medford From 1630–1885 (Boston: Rand, Avery, & Co., 1886).

The quoted passage is in The Massachusetts Abolitionist 2, no. 43 (December 10, 1840). There is also mention in the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society Reports of Anti-Slavery Fairs with “bazaars” being staged during the 1840s at Boston’s Faneuil Hall, as well as Salem, Fitchburg, Upton, Uxbridge, Milford, Hingham, Nantucket, Worcester, West Winfield, New Bedford, Weymouth, and elsewhere. The largest seems to have been an annual Christmas fair, held at Amory Hall and then at Faneuil Hall. In the 1843 report it is mentioned that the Christmas fair “was furnished from many towns in the State.” On August 1, 1843, a celebration with a parade, banquet, and “an elegant collocation furnished by general contribution” was held in Dedham in honor of the anniversary of the emancipation of the West Indian slaves. The Dedham celebration is mentioned in Twelfth Annual Report Presented to the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, January 24, 1844, pp. 44–45.

Middlesex Deeds, 384:118 and 408:515. Stephen’s use of the term “sable,” which originally appeared in The Opportunity (London, 1804), is quoted in David Geggus, “Haiti and the Abolitionists: Opinion, Propaganda and International Politics in Britain and France, 1804–1838,” in David Richardson, editor, Abolition and Its Aftermath: The Historical Context, 1790–1916 (London: Frank Cross, 1985), p. 115.

Lawrence W. Levine, Highbrow/ Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988), pp. 1–22.

George F. Tyson, Jr., Toussaint L’Ouverture, pp. 1–2.

The physical descriptions of Toussaint noted in this paper, and many additional period references, appear in Tyson, pp. 89–154.

Hugh Honour, The Image of the Black in Western Art, vol. 4, From the American Revolution to World War I, part 1, Slaves and Liberators (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989), p. 109.

David Geggus, “The Haitian Revolution,” in Hilary Beckley and Verene Shephard, Caribbean Slave Society and Economy: A Student Reader (Kingston, Jamaica: Ian Randle, 1991), p. 413.

The earliest known image of Toussaint was a hostile caricature, published in Francois Bonneville’s Portraits des Personnages Célèbres de la Revolution (Paris, 1802); Bonneville also published a pamphlet attacking Toussaint and his “horrible crimes” in the same year. Tyson’s book records most of the known period descriptions of Toussaint. Tyson, Toussaint L’Ouverture, pp. 132, 79. See also Honour, The Image of the Black in Western Art, pp. 105–9.

Eugene Genovese, From Rebellion to Revolution: Afro-American Slave Revolts in the Making of the Modern World (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979), p. 95. Thanks to Susan V. Donaldson for this reference and for providing a copy of a lecture, entitled “Southern Narrative and Haitian Shadows.”

William Wells Brown, St. Domingo: Revolutions and Its Patriots (Boston: Bela March, 1855), p. 32, quoted in Donaldson, “Southern Narrative.”

James Brewer Stewart, Wendell Phillips: Liberty’s Hero (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1986), pp. 104–5.

David Walker, Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World (1829; reprint, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2000 ), p. 23.

Tyson, Toussaint L’Ouverture, p. 132.

Geggus in Richardson, ed., Abolition and Its Aftermath, p. 114.

Eleventh Annual Report Presented to the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society by Its Board of Managers (Jan. 25, 1843), p. 27. Five years previously, two men had been sent by the American Anti-Slavery Society on a similar trip to the free English-speaking islands of the West Indies, and they concluded that “the emancipated people are perceptibly rising on the scale of civilization, morals, and religion. Reason cannot fail to make its inferences in favor of two and a half millions of slaves in our republic.” Horace Kimball and James A. Thome, Emancipation in the West Indies: A Six Month Tour in Antigua, Barbadoes, and Jamaica, in the Year 1837 (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1838).

On colonization, see P. J. Staudenraus, The African Colonization Movement 1816–1865 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), pp. 82–87; Ludwell Lee Montague, Haiti and the United States 1714–1938 (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1940); William Lloyd Garrison, Thoughts on African Colonization (Boston: Garrison and Knapp, 1832); G. B. Stebbins, Facts and Opinions Touching the Real Origin, Character, and Influence of the American Colonization Society (Boston: John P. Jewett & Co., 1853); Early Lee Fox, The American Colonization Society 1817–1840 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1919).

Saunders is quoted in Alice M. Dunbar, Masterpieces of Negro Eloquence (New York: Bockery, 1914), p. 14.

Earl Leslie Griggs and Clifford H. Prator, Henry Christophe – Thomas Clarkson: A Correspondence (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1952), p. 68.

James Redpath, editor, A Guide to Hayti (Boston: Thayer & Eldridge, 1860); Staudenraus, The African Colonization Movement, pp. 244, 247.

Maria Weston Chapman, Memorials of Harriet Martineau (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Co., 1877), pp. 334–52; Harriet Martineau, The Hour and the Man: A Historical Romance (London: Edward Moxon, 1843). For more on Martineau see Adam Lively, Masks: Blackness, Race and the Imagination (London: Chatto & Windus, 1998), pp. 84–85.

Wendell Phillips, “Toussaint L’Ouverture,” in Wendell Phillips, Speeches, Lectures, and Letters (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1863), pp. 468–94; Maria Weston Chapman, Memorials, p. 352. For a competing but less frequently stated abolitionist use of the Haitian revolution, which presented the event as a cautionary tale about the inevitable violence created by slavery, see An Essay on the Late Institution of the American Society for Colonizing the Free People of Color, of the United States (Washington, 1820), pp. 33–59.

Peter T. Nesbett and Michelle DuBois, editors, Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000); Nesbett and Michelle DuBois, Jacob Lawrence: Paintings, Drawings, and Murals (1935–1999), A Catalogue Raisonné (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000), pp. 27ff. The cycle of paintings has also been used as the basis of a children’s book, Walter Dean Myers’ Toussaint L’Ouverture :The Fight for Haiti’s Freedom (New York : Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 1996).

James Theodore Holly, A Vindication of the Capacity of the Negro Race for Self-Government, and Civilized Progress, as Demonstrated by the Events of the Haytian Revolution (New Haven, Conn.: Afric-American Printing Co., 1857), p. 48.