Pitcher, possibly Medford, Massachusetts, ca. 1840. Earthenware. H. 13". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This slip cast pitcher is one of four known. Two are impressed on the base with “MEDFORD” suggesting Medford, Massachusetts, as their place of manufacture. Nothing is known about the modeling of the original or the subsequent production of the molds. All of these jugs have a characteristic buff earthenware body with a thick Albany slip glaze that varies from shades of dark brown to almost black. The illusion of teeth is the result of scraping away the Albany slip to expose the buff color of the clay body.

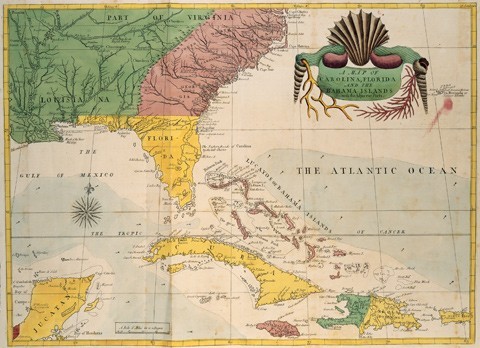

Mark Catesby, Map of Carolina, Florida, and Bahama Islands with the Adjacent Parts, London, 1754. (Private collection.)

Detail of the map illustrated in fig. 2 showing the island of Hispanola. Its aboriginal inhabitants originally knew the island as Haiti. The Spanish changed the name to Santo Domingo, and in 1697 the formal division of the island into Santo Domingo and Saint-Domingue took place. In 1804, Saint-Domingue ceased to exist and was renamed using the early term Haiti.

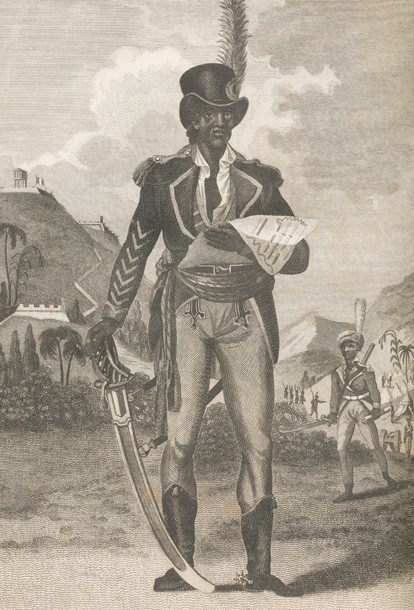

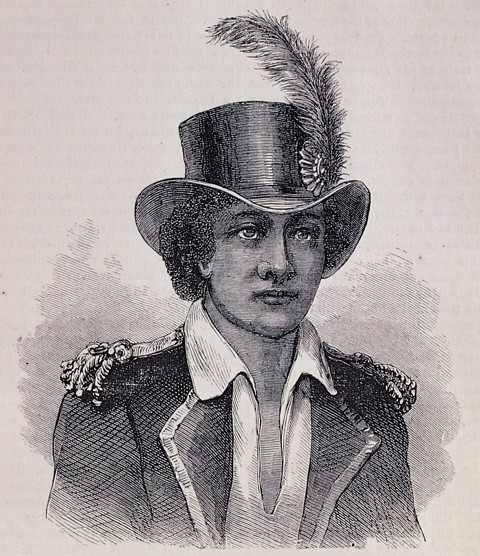

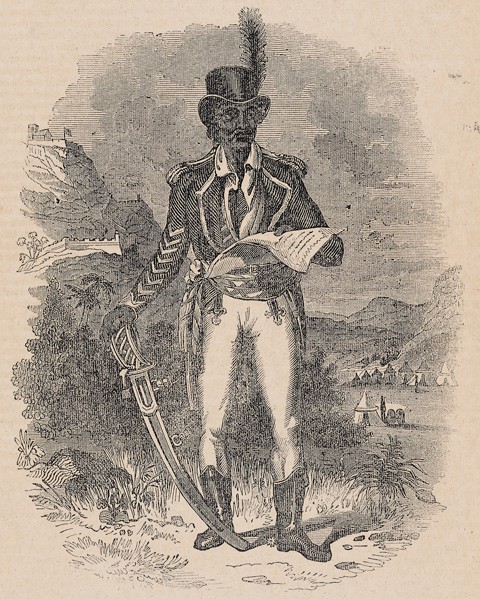

Marcus Rainsford, Toussaint L’Ouverture, London, 1805. (Courtesy, Archives & Special Collections, University of Miami Library.) This is the earliest known image of Toussaint L’Ouverture taken from sketches made by Marcus Rainsford. It appeared as an illustration in Rainsford’s An Historical Account Of The Black Empire Of Hayti: Comprehending A View Of The Principal Transactions In The Revolution Of Saint Domingo; With Its Ancient And Modern State. Toussaint is represented as a dignified military leader with a sword in one hand and a battle map in the other.

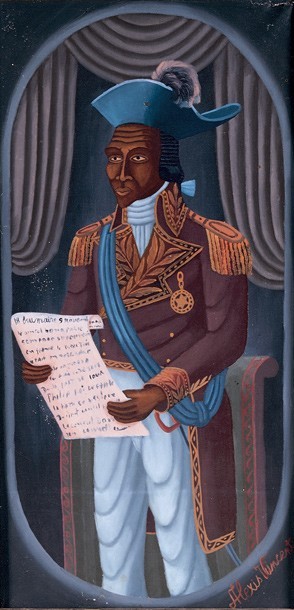

Alexis Vincent, Toussaint L’Ouverture, Haiti, ca. 1970. Oil on canvas. (Private collection.) The image of Toussaint is commonly evoked by contemporary Haitian folk painters. Vincent’s painting is reflective of the twentieth-century self-taught Haitian artists who began to make their contribution to Haitian life and cultural expression in the 1940s and 1950s. In this painting, Toussaint is depicted in a similar pose to the Marcus Rainsford engraving except that a commemorative scroll or proclamation has taken the place of the map.

Detail of the impressed “medford” stamp on the base of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 8. (Private collection; photo, Jay Lewis.)

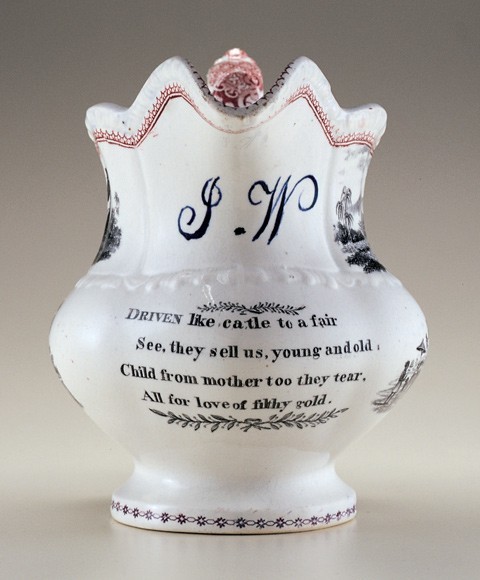

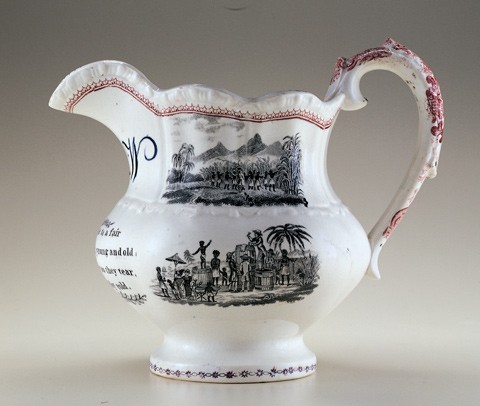

Pitcher, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1840. Earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Inscribed with the initials “J.W.” and the verse “DRIVEN like cattle to a fair; See they sell us, young and old. Child from mother too they tear, All for love of filthy gold.” This rare transfer-printed jug made for the abolitionist market contains graphic scenes of slavery in the West Indies. Note the general overall shape, handle, and rim characteristic of ca. 1840 classical or Greek Revival styles in English and American pottery and porcelain.

Pitcher, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1840. Earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Inscribed with the initials “J.W.” and the verse “DRIVEN like cattle to a fair; See they sell us, young and old. Child from mother too they tear, All for love of filthy gold.” This rare transfer-printed jug made for the abolitionist market contains graphic scenes of slavery in the West Indies. Note the general overall shape, handle, and rim characteristic of ca. 1840 classical or Greek Revival styles in English and American pottery and porcelain.

Pitcher, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1840. Earthenware. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, Rex Stark; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Inscribed with the initials “J.W.” and the verse “DRIVEN like cattle to a fair; See they sell us, young and old. Child from mother too they tear, All for love of filthy gold.” This rare transfer-printed jug made for the abolitionist market contains graphic scenes of slavery in the West Indies. Note the general overall shape, handle, and rim characteristic of ca. 1840 classical or Greek Revival styles in English and American pottery and porcelain.

Pitcher, possibly Medford, Massachusetts, ca. 1840. Earthenware. H. 13". (Private collection; photo, Jay Lewis.) This example of the Toussaint L’Ouverture pitcher has an extremely dark brown, almost black, Albany slip. The outline of the eyes have been highlighted by scratching through the slip suggesting that although these pitchers were made from the same model, they could be individualized by the potter.

Detail of the unmarked base from pitcher illustrated in fig. 1. The fingerprints of the potter who dipped the pitcher in Albany slip have been recorded on its base.

Side view of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 1. (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

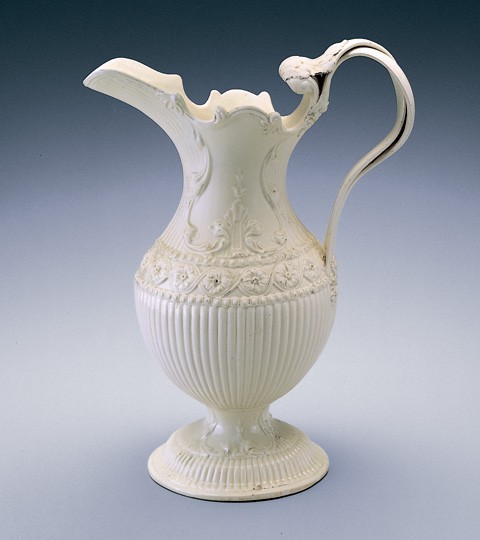

Ewer, Leeds, ca. 1790. England. Creamware. H. 11 1/4". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This late eighteenth-century ewer, inspired by antique Greek and Roman examples, exhibits molded frieze-like elements on the neck and body similar to the grammar of the design elements representing the military cap on the L’Ouverture pitcher.

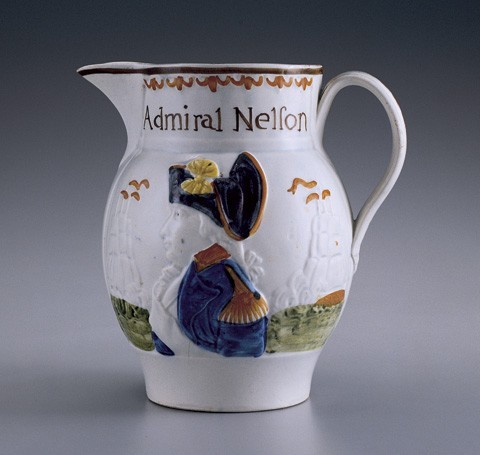

Jug, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1805. Pearlware. H. 6 1/8". (Chipstone Foundation, Noël Hume Collection.) Drinking jugs and pitchers have been made to commemorate cultural heroes and promote political messages since antiquity. In the late eighteenth century, with the rise of the Staffordshire potteries, large quantities of molded commemorative wares were made for middle-class consumers in the Anglo-American market.

Pitcher, possibly Medford, Massachusetts, ca. 1840. Earthenware. H. 13". (Courtesy, Arthur Goldberg.) Also marked “MEDFORD,” this pitcher has the illusion of teeth like the example shown in fig. 1.

Rear view of the pitcher illustrated in fig. 13. (Courtesy, Arthur Goldberg.)

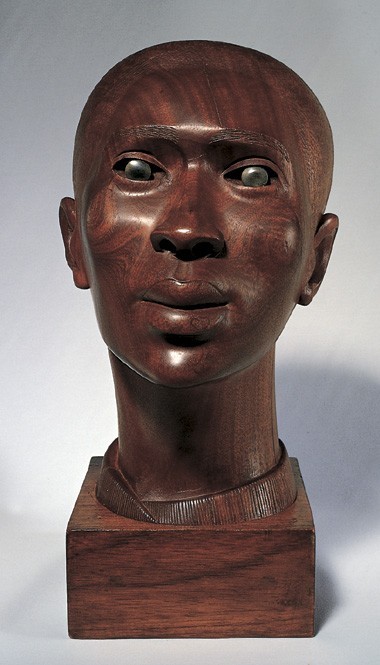

Elizabeth Catlett, Negro Woman, ca. 1956. Wood and onyx. H. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, Clark Atlanta University Art Galleries ©.)

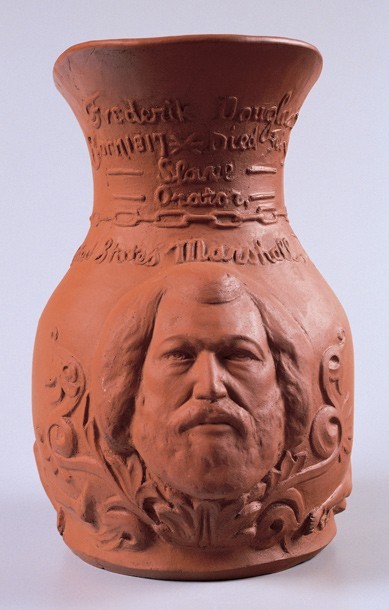

Pitcher designed and copyrighted by J. E. Bruce, Albany, New York, 1896. Unglazed red earthenware. H. 10 1/4". (Courtesy, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Although not directly related to the Toussaint L’Ouverture pitcher, this object attests to the use of ceramics vessels as the means for conveying important historical and political concerns. Hand modeled and molded, the pitcher bears the inscription: “Frederick Douglass/Born 1817/Died Feby 20 1895/Slave Orator/ United States Marshall, Recorder of Deeds D.C./Diplomat.”

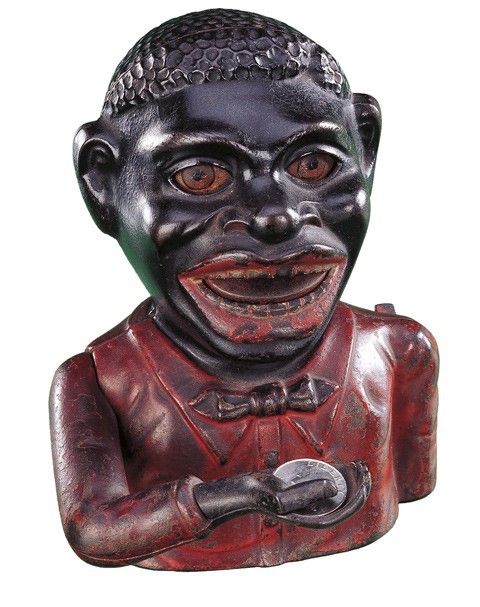

Jolly Nigger Mechanical Bank, J. & E. Stevens Co., Cromwell, Connecticut, patented March 14, 1892. Cast iron. H. 6". (Courtesy, Larry Vincent Buster, The Art and History of Black Memorabilia [New York; C. Potter, 2000]; photo, Kenneth Paul, Sr.)

Face jug, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1860. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 6". (Private collection.

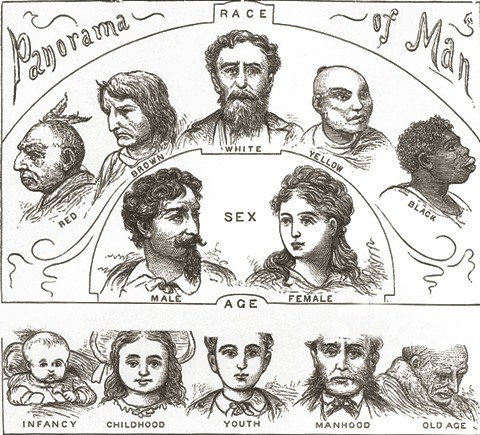

by Nelson Sizer and H. S. Drayton, A.M., M.D., Heads and Faces and How to Study Them (New York: Fowler & Wells Co., 1891.) (Chipstone Foundation.

Eugenie Lebrum, Toussaint L’Ouverture, General en chef à St. Domingue, Paris, 1825. (Private collection.) This image of Toussaint appears as the frontispiece in a history of Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition in Haiti.

Toussaint L’Ouverture from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine 43, no. 253 (1871). (Private collection.) In contrast to the image portrayed in the 1838 Penny Magazine, this image, also after the Rainsford engraving, shows a young, almost boyish, Toussaint.

Engraving from The Penny Magazine, (London: Published by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, 1838). (Private collection.) This depiction of Toussaint L’Ouverture appeared on the cover of Penny Magazine in 1838. The magazine contained a wide range of informative illustrated articles and was aimed at the working class. The 1805 Rainsford engraving is the obvious source of this image although Toussaint’s facial features have been given a much harsher look.

Nicolas Eustache Maurin, Toussaint L’Ouverture, from Iconographie des Contemporains, Paris, 1832. Lithograph. (Courtesy, Print & Picture Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia.) With its “ape-like” profile, this was the most frequently reproduced image of Toussaint during the period in which the portrait pitcher was modeled.

Engraving of Harriet Martineau, 1802–1876. (Chipstone Foundation.)

Jacob Lawrence, The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture, No. 21: General Toussaint L’Ouverture attacked the English at Artibonite and there captured two towns, New York, 1938. Tempera on paper, 11 1/2" x 19". (Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans. Aaron Douglas Collection. Artwork © Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, courtesy of the Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation.)

Jacob Lawrence, The Life of Toussaint L’Ouverture, No. 20: General Toussaint L’Ouverture, Statesman and military genius, esteemed by the Spaniards, feared by the English, dreaded by the French, hated by the planters and reverenced by the Blacks, New York, 1938. Tempera on paper, 19" x 11 1/2". (Amistad Research Center, Tulane University, New Orleans. Aaron Douglas Collection. Artwork © Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, courtesy of the Jacob and Gwendolyn Lawrence Foundation.) Toussaint L ‘Ouverture was the first of Lawrence’s many major series. Researched and created from 1937–1938, and completed when he was only twenty-one, the paintings thrust Lawrence onto the national art scene.