A portion of the Bruce Coleman Perkins Collection on display in his home.

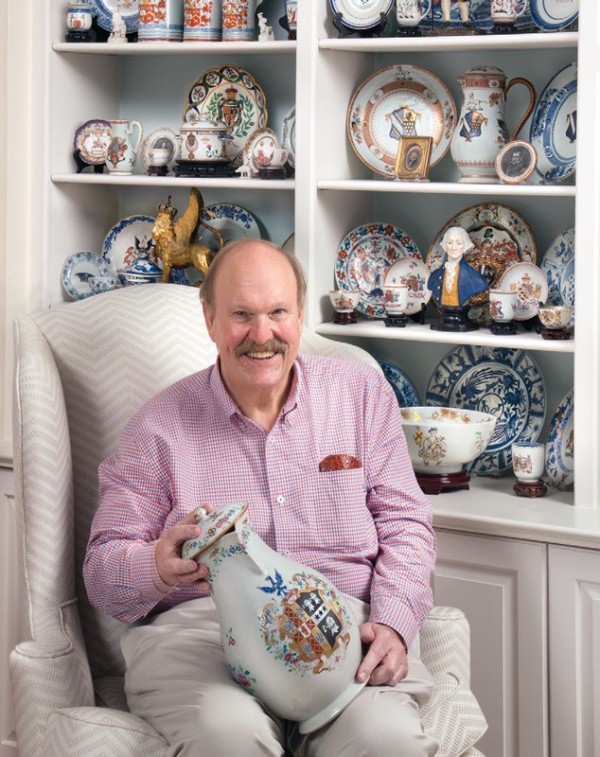

The collector with one of his favorite pieces.

Tureen, made in Jingdezhen and decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1820–1825. Hard-paste porcelain. L. 13 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This tureen, decorated in the Fitzhugh pattern, is from a service that belonged to Charles Irénée

du Pont (1797–1869) and his wife, Dorcas van Dyke (1806–1838). They married in 1824 and the service is thought to have been a wedding gift.

Plate with the arms of Cutler, made in Jingdezhen and decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, ca. 1790. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 9 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This plate is from a service made for Henry Cutler of Sidmouth, England, who married Katherine Olive in 1788. The service may have been made to celebrate their wedding.

Mugs with the arms of Gough impaling Hynde, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1720. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 6 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These three mugs are decorated in the Imari palette of underglaze blue and overglaze red and gold. They are from one of the four Chinese armorial porcelain services that were made for Harry Gough (1681–1751) and his wife, Elizabeth Hynde (1699–1774). Gough spent his career working for the East India Company, which gave him the wealth and connections needed to commission armorial porcelain.

Plate with the arms of the Duke of Clarence, Flight’s Worcester Porcelain Factory, Worcester, England, ca. 1789. Soft-paste porcelain. D. 10". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This plate, which comes from the first royal armorial service made at Worcester, was commissioned by William Henry, Duke of Clarence and Saint Andrew, who later became King William IV of Great Britain and King of Hanover (1765–1837). It was made to celebrate his elevation to the Dukedom of Clarence and Saint Andrew in 1789.

Charger with the arms of Pitt, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1705. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 14 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This charger is from a service made for the China trade merchant Thomas Pitt (1653–1726. Pitt’s wealth helped establish a political dynasty that included two prime ministers: his grandson William Pitt the Elder (1707–1778) and his great-grandson William Pitt the Younger (1759–1806).

Plate with the arms of Pitt with Ridgeway in pretence, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1720. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 8 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This plate is from a service made for Thomas Pitt, Baron (later Earl) of Londonderry, and Frances Ridgeway, who married in 1718. Frances had no brothers, meaning she would inherit her father’s estates, which is shown by her arms being placed on a small shield “in pretence” or on top of her husband’s shield.

Plate with the arms of Pitt impaling Grenville, made in Jingdezhen and decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, ca. 1772. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 8 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The service from which this plate comes was a gift from the British East India Company to William Pitt the Elder (1707–1778), Great Britain’s first prime minister, and his wife, Hester Grenville, Viscountess Cobham (1720–1803).

Ecuelle with arms of France, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1725. Hard-paste porcelain. L. 6 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This ecuelle, or covered bowl, is from a large service possibly made for Louis XV (1710–1774), king of France.

Detail of the ecuelle illustrated in fig. 10.

Plate, teabowl, and saucer with monogram of the VOC, made in Jingdezhen, China, 1728–1730. Hard-paste porcelain. D. of plate 9". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These pieces are decorated with the arms of the Dutch Republic with the motto Concordia res parvae crescent (through unity small things become greater). The design is copied from a silver ducatoon, a coin struck for use by the Verenigde Oost-indische Compagnie, or Dutch East India Company, in Asia. The monogram of the VOC is painted in the interior of the cup.

Interior of the teabowl illustrated in fig. 12.

Soup plate with the arms of Elwick, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1730. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 8 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Combining an English coat of arms with a Chinese landscape scene, this soup plate comes from a service made for John Elwick (d. 1730) of London. Like many people who commissioned armorial porcelain in the first half of the eighteenth century, John had links with the China Trade, serving as a director of the East India Company.

Jug with the arms of Mawbey impaling Pratt, made in Jingdezhen and decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, ca. 1766. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 15". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This massive beer jug, one of a pair, was made for Sir Joseph Mawbey (1730–1798), an English distiller and member of Parliament and his wife, Elizabeth Pratt (d. 1790).

Detail of the arms on the jug illustrated in fig. 15.

Charger with the arms of Haldane, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1725. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 14". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This charger was part of a service made for a member of the Haldane family of Gleneagles, Scotland. Like many armorial services, the coat of arms is copied from a bookplate. Bookplates were a convenient way of sending an image of one’s arms to China to be copied, but in this, one of the earliest known uses of a bookplate as a design source, no one provided instructions that the printed border was not to be copied.

Coffee cup and saucer with the arms of Tower, and coffee cup and saucer with the arms of Skinner, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1730. Hard-paste porcelain. Saucer D. 4 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These two cups and saucers, which match except for the coat of arms, were commissioned at the same time and most likely were decorated in the same workshop. The one on the left was made for either Christopher Tower (1694–1771) or Thomas Tower (1698–1778), brothers who served as lawyers, politicians, and as trustees of the Colony of Georgia. The one on the right was made for Matthew Skinner (1689–1749), a sergeant at arms, judge, and member of Parliament.

Punch bowl, Jingdezhen, China, 1743–1750. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 11 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Probably made for a Jacobite sympathizer—someone who supported the deposed Stuart dynasty of England, Ireland, and Scotland—the exterior of this bowl is decorated with a Scottish private and piper (seen here) from the First Highland Regiment of the British army. The image of the piper is based on the frontispiece of A Short History of the Highland Regiment, published in London in 1743, which was also sold as an individual print. Drinking toasts to the exiled Stuarts was a popular way for Jacobites to show their support, and wine glasses, beer mugs, and punch bowls with Jacobite imagery were made to facilitate those rituals.

Punch bowl, Jingdezhen, China, 1743–1750. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 11 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Probably made for a Jacobite sympathizer—someone who supported the deposed Stuart dynasty of England, Ireland, and Scotland—the exterior of this bowl is decorated with a Scottish private and piper (seen here) from the First Highland Regiment of the British army. The image of the piper is based on the frontispiece of A Short History of the Highland Regiment, published in London in 1743, which was also sold as an individual print. Drinking toasts to the exiled Stuarts was a popular way for Jacobites to show their support, and wine glasses, beer mugs, and punch bowls with Jacobite imagery were made to facilitate those rituals.

Detail of the interior of the punch bowl illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Within the bowl is a portrait of Charles Edward Stuart (1720–1788), popularly known as Bonnie Prince Charlie. The grandson of King James, the deposed king of England and Scotland, he claimed the throne of Great Britain. In 1745 he led an invasion of Britain that came close to succeeding; he gathered supporters in Scotland and led an army as far south as Derby in England before retreating back into Scotland, where he was defeated at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. He remained in exile in Europe for the rest of his life.

Charger and coffeepot with the arms of Krueger,made in Jingdezhen and decorated in Guangzhou (Canton),China,ca. 1740. D. of charger 15 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These pices are decorated with an elaborate Continental European armorial, probably that of Krueger family of Austria.

Soup plate with the arms of Van Hardenbroeck, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1734. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 8 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This eggshell-thin soup or dessert plate was probably made for Johann Louis van Hardenbroeck (1691–1747), a ship’s captain who served in the Admiralty of Amsterdam and later as a member of the States-General, the governing body of the Netherlands

Plate with the arms of Lee, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1733. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 9". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Much of the armorial porcelain illustrated in this article would have gone through the two ports—London and Guangzhou (Canton)—painted on the rim of this plate. In the center is the arms of the Lee family of Coton, England. The Lees of Virginia, including Robert E. Lee, one of the namesakes of Washington and Lee University, used these arms from the time they arrived in Virginia in the seventeenth century.

I WAS FORTUNATE TO HAVE been born into a family of collectors (figs. 1, 2). I grew up in a beautiful home in a Washington, D.C. suburb. My home was full of wonderful period American art and antiques inherited from my mother’s family: Philadelphia Chippendale, Baltimore Federal, and paintings by Homer, Hassam, and Prendergast. Strongly influenced by the work done at the Winterthur Museum and Colonial Williamsburg, our house was a big red-brick colonial with the front hall and living room painted Hammond Harwood Green.

One of four brothers, I was the only one to get the collecting bug and, like many of my fellow collectors, I started early, first with Steiff stuffed animals, then rocks and shells, pocketknives, beer cans, beer mugs, and eventually Chinese export porcelain. I was thrilled when my older brother Howard moved into a bedroom of his own and I, at age eight, got a room to myself and immediately began filling it with my treasures. The room had twin beds and all my stuffed animals were carefully displayed on the spare bed, and my other objects were carefully displayed in my bookshelves. I am still teased for not using bookshelves to hold my books! After a long day at school, I loved to retreat to my third-floor bedroom, separated from everyone else, surrounded by my precious objects.

My mother was from Wilmington, Delaware, and we made regular visits to my grandmother’s home there. Every year we would stay there for a week or two so that my parents could go away on vacation. Granny’s house, Goodstay, was an eighteenth-century house that had been the boyhood home of the artist Howard Pyle. It had been acquired by my family in the 1860s, and in the 1920s and 1930s my grandmother greatly expanded it. She too was a collector, so every nook and cranny were full of wonderful objects. One rainy day I was exploring the third floor and found a small doorway that led to a large attic storage space. Under the eaves were trunks, suitcases, and boxes that had not been opened for generations. Each one was packed full of wonderful objects that had belonged to my ancestors. For me, it was a dream come true and I spent many happy hours digging through everything looking for treasures. After discovering this space, I looked forward to all visits to Granny’s house.

My first recollection of seeing Chinese porcelain was in Wilmington. We routinely went to Granny’s house for major holidays: Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter. On those special occasions we would have dinner served on “The Admiral’s China,” a beautifully painted brown Fitzhugh service that had descended in the family and was highly revered (fig. 3). Admiral Samuel Francis du Pont (1803–1865) was my grandmother’s great-great uncle, and in the course of his long naval career he had gone to Asia right after Admiral Perry and brought back a number of pieces of Chinese and Japanese furniture and accessories. The story I was told was that he had purchased this service on that trip. However, the service predates his trip by decades, so the story that I grew up hearing was wrong. In fact, the service had belonged to his brother Charles Irénée du Pont (1797–1869) and his wife, Dorcas van Dyke du Pont (1806–1838), who married in 1824. Most likely it was a wedding present to them.

My grandmother also had a green Fitzhugh service that was used for special occasions. It was explained to me that the Fitzhugh pattern had been available in many other colors—blue, yellow, and orange.

I attended Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia, along with one of my brothers. During my junior year there, my parents happened to attend a dinner party at Winterthur Museum where they heard about a wonderful collection of ceramics that had been left to the university by Euchlin Reeves, a graduate of the law school, and his wife, Louise Herreshoff. They decided to kill two birds with one stone: go to Lexington and visit their sons, and see the collection. At that time I was more fascinated with American furniture and paintings, but at my mother’s urging I reluctantly went along for the tour. On that fateful day I met the man who changed my life, James Whitehead. Mr. Whitehead was the treasurer of the university and had been given the task of dealing with this unusual gift. The collection contained almost every type of ceramic imaginable, but it had an especially large and impressive assortment of Chinese export porcelain. While we were rooting through one of the large barrels, Mr. Whitehead asked me if I would like to come and work for him, to help catalog, clean, research, and sort out this wonderful collection. My mother immediately said, “Bruce would love to!” I was not sure what I would be getting into, but with a lot of hesitation, I agreed.

Within a week, Mr. Whitehead’s infectious enthusiasm began rubbing off on me. They had brown Fitzhugh like my grandmother’s, but also orange, yellow, black, and mulberry! At first, I was drawn to the pieces that had ships, flags, and/or other patriotic themes. However, I also became fascinated by the eighteenth-century pieces decorated with coats of arms, an interest that has remained strong to this day.

Mr. Whitehead and I decided that I should concentrate on the Chinese export since I was already familiar with it. At the time (1972–1973) there were not many scholarly books on the subject, so we decided that I should take some of the unknown pieces to experts for help with identification. Whenever I would head back to Washington, D.C., I would load up the trunk of my Camaro with twenty or thirty pieces of porcelain packed in cardboard boxes with tissue and head north. Mr. Whitehead had befriended a very knowledgeable dealer in Georgetown by the name of Michael Arpad. With his valuable assistance, we were able to better understand and identify the treasures that Washington and Lee had been given.

Another dealer who was extremely helpful to us was Elinor Gordon. She and her late husband, Horace, had sold the Reeves several important pieces. Mrs. Gordon was very generous with her knowledge and time, and was of tremendous assistance to us as we sorted out what was good and what was not. I was very lucky to have spent the next year and a half working with Mr. Whitehead, learning more and more about this porcelain that I loved.

I turned twenty-one while still a student at Washington and Lee, and my parents gave me $500 for my birthday with the instructions to buy whatever I wanted. I immediately went to Georgetown to see Mr. Arpad, who told me about another dealer in Georgetown who had a good selection of armorial porcelain. As I walked into that store, I saw a pair of plates with the arms of Cutler circa 1790 (fig. 4).[1] I loved them and they were in my price range, so I purchased them and brought them home. My mother was thrilled, although my father, who loved wood working, was disappointed that I had not purchased something practical like a bandsaw. I, of course, was very pleased with my purchase.

I attended graduate school at the University of Delaware studying art history. While there I was able to take a few of my classes at Winterthur and was fortunate to get to know Arlene Palmer, the new curator of ceramics at the museum. She was incredibly kind to me and took me through the museum’s comprehensive collection of porcelain, about which, thanks to her, I began to learn more and more. Her kindness helped spark my fifty-year love affair with Winterthur. I’m proud to say that I have now served on Winterthur’s board for thirty years.

After my time at the University of Delaware, I returned to Washington, D.C. and attempted to determine how I was going to make a living. After my first “real” job as an insurance claims adjuster, I worked in the trust department of a large local bank, then went through management training program at Garfinkel’s (the high-end local clothing store in Washington). While at Garfinkel’s, I learned a great deal about the retail business, but most importantly I learned that I was never going to make enough money in that field to allow me to continue collecting. It was at that point that I had the brilliant idea of having my own antiques business. Through this newest venture, I thought I would be able to live well and continue to collect. Good family friends lived outside of Middleburg, Virginia, which seemed like a perfect place to start my new business. Over the next five years I attempted to live my dream and sell fine antiques. Business was not too bad, and I loved living in the countryside. However, I discovered that most of the better clients were buying in New York, London, or Paris, not Middleburg. I had a good assortment of antique English and American furniture, and Chinese export porcelain (mostly late-eighteenth-century pieces). I learned quickly that the clients I assumed I would be dealing with had no interest in dealing with me; their main concern was to get the best possible price. While my knowledge expanded greatly and I made many friends, I realized that financially I was not going to be able to add to my personal collection the way I wanted to if I was to succeed as a dealer! It slowly became apparent to me that I would be better off working for someone else and making enough money to pay my bills and collect porcelain.

They say that good things come to those that wait, and in 1982 my old boss at Washington and Lee, James Whitehead, contacted me and informed me that he was on the board of a new group, the Decorative Arts Trust, and they were putting together a major symposium at Washington and Lee on Chinese export porcelain that he thought I should attend. I signed up immediately and was excited at the prospect of meeting the key players in the Chinese export porcelain world. The lecturers were all the great scholars, dealers, collectors in this specialized area. I loved it and, more important, met and became friends with many of them, including the collectors Pamela Copeland and Jim and Nancy Flather, the dealer and scholar David Sanctuary Howard, and curators Bill Sargent and Crosby Forbes from the Peabody Essex Museum.

As I sat through that fabulous weekend, I fell even more in love with export porcelain. Early on, I decided that I wanted to focus on armorial pieces embellished with coats of arms. One of the speakers at the symposium was David Sanctuary Howard, and since I had decided to collect armorial porcelain, he was a “must know.” I explained to him that I had a very limited budget but really wanted to expand my collection. He told me that he too had a limited budget for his own collection, so he was collecting armorial coffee cups and, even though they are small, the quality of the painting was just as good as it was on a punch bowl. I learned so much from this weekend in Lexington, and it opened me up to collecting smaller pieces, which I have continued to do to this day.

At the Washington and Lee weekend I also met a person who became a big influence on my collecting. Charles B. Perry was a private dealer out of Atlanta. Charles was large and loud but a brilliant dealer who sold only export porcelain. He introduced me to many of the great eighteenth--century armorial services, and thanks to his encouragement I began collecting pieces from the mid-eighteenth century. As I transitioned from dealer to collector, Charles Perry became my main resource.

The Decorative Arts Trust meeting in Lexington changed my life. One of the lecturers that weekend was Jim Flather from Washington, D.C. Jim and his wonderful wife, Nancy, had put together a beautiful collection of Chinese porcelain decorated in the Imari palette of blue, red, and gold (fig. 5). We talked at that meeting and the Flathers invited me to see their collection. In the following months, we met for lunch and although the talk was mostly about porcelain, Jim offered me a job to come to his firm and specialize in fine arts insurance. At that time, my business was very slow, and the offer seemed like a wonderful idea. I had a sale at my antiques shop and sent the remaining items to auction. Early in July 1983, I transitioned from selling fine arts to insuring fine arts. I loved working for Mr. Flather, and over the next few years I began to build a base of top-level antiques dealers and collectors as clients. When I was still a dealer back in Middleburg, I had befriended a lovely collector from the Hartford area of Connecticut named Barbara Mayer who was also a fan of Chinese export porcelain. I had sold her several pieces and when I told her that I was going into the fine-arts insurance business, she immediately invited me to Connecticut to stay with her and her husband, and while I was there she introduced me to the top-level dealers, collectors, and museum people in this antique-rich state. I will be forever grateful to them for their generosity and kindness which helped start my new career.

While visiting with Barbara during the opening of the Hartford Antiques show, I found an exceptionally beautiful English armorial dish that was unlike anything that I had ever seen before, but I did not know what it was (fig. 6). Unfortunately, I was unable to come up with the money to purchase it (I had just returned from my first trip to England and was absolutely broke!). Being the kind of person that she was, Barbara offered to buy it and add it to her collection until I was ready and able to purchase it from her. I never stopped thinking about that dish until I was finally able to buy it from her several years later. Decades later, even after I had added several important and beautiful Chinese armorial pieces to my collection, this one English dish still stands out as one of my favorite pieces. When I bought it, I did not know exactly how good this piece was but felt that it had to be important. The American Ceramic Circle was having a meeting in Baltimore the following year, so I took it to the meeting. I showed it to the “Dish Queen” of Sotheby’s, Letitia “Tish” Roberts, and after one quick look at it she identified as part of the service ordered in 1789 by Prince William Henry (1765–1837, later King George IV of Great Britain) to commemorate his being made the Duke of Clarence. It was the first royal service made at Worcester and one of the most expensive ever ordered.[2] Although it was not Chinese and not quite what I was collecting, it has been a highly prized piece of my collection ever since.

The ACC meeting in Baltimore was important to me because I was surrounded by a group of scholars and collectors who loved to share their knowledge about ceramics. Jim Whitehead had decided to step down from two boards that he was on and he recommended that I be his replacement on not only the Ceramic Circle board but also the Decorative Arts Trust board. I gladly agreed to serve on both. At about that same time, I was asked to join the Friends of Winterthur (which I also accepted). The Friends was the support group for the museum and after a few years on the board of the Friends, I was asked to join the board of trustees of Winterthur.

One of the many great perks of being involved with a museum or a collector’s organization is that there is always an opportunity to travel and visit the wonderful private homes and collections and get to know them. My first international museum trip of this kind was a special tour for the Winterthur board that was guided by Thomas Savage, who at the time was running Sotheby’s education programs. Tom was asked to put together a trip for the Winterthur board to study how large, active English country estates managed themselves. Since I was mostly collecting armorial porcelain for the English market, this English country house tour seemed like a dream come true—and it was! Our group met in London, boarded a bus, and set out for County Devon where we were guests at Castle Hill, a beautiful house set in the middle of a 10,000-acre estate.

We entered the house, and in the front hall was a pair of large, early Chinese armorial chargers with the arms of Thomas Pitt (1653–1726), a China trade merchant who made a fortune purchasing an enormous diamond in India which he sold to the French royal family (fig. 7).[3] His armorial porcelain service was one of the earliest ever made for the English market, and I had never seen a piece in person. I said, “You have the Thomas Pitt service?” and our hostess was so pleased that I knew the service that she proceeded to explain that she was a direct descendant of Pitt and that they had inherited the family service.

As we entered the other magnificent rooms, we saw great armorial porcelain everywhere. All had been ordered by, or for, her family. I had been spoiled as a child visiting my grandparents’ large homes full of treasures, but this home was in a whole different category. Everything had a story, one better than the last! I will be forever grateful to Tom Savage for setting this trip up.

After visiting many other great English estates, both private and public, we returned home. Even though we saw so many wonderful places and things, I was haunted by the early rare Pitt service that we had seen at Castle Hill, and I was determined to somehow acquire a piece from it. Upon my return to the states, I also discovered there were two more Pitt services. One for Thomas Pitt’s son, also named Thomas, and one for his grandson William Pitt, the Earl of Chatham. William Pitt had been a well-known politician who went on to become the English prime minister during the American Revolution and supported the American cause (figs. 8, 9).[4] Since I also collect eighteenth-century prints relating to the American Revolution, it seemed logical that I should obtain a piece from his service as well. It took quite a while, but eventually I was able to purchase examples of the three generations of the Pitt family. I am now able to show and talk about the story of the remarkable family whose fortune started with one big diamond.

Up until this point, I was collecting very pretty armorial pieces from the second half of the eighteenth century, primarily plates and dishes. After the Winterthur trip to England, I realized that I needed to change my focus to the 1730s and 1740s, when the quality of porcelain and enameling was at its best. At the same time, a friend took some pictures of my shelves of porcelain and in looking at the photos I realized that if I wanted a very fine collection, I also needed to start buying the many different forms and shapes. Although I love plates, putting together a wall of them with no other forms can be very boring (see fig. 1).

As I was fine-tuning my collecting philosophy, I thought it would be interesting to add more porcelains made for royalty. I had been fortunate to purchase the Duke of Clarence (later King George IV) dish years before, so I had a great example of English royal ceramics. However, my piece was made in England and all the rest of my collection was made in China. After several years, I was finally able to purchase a Chinese export porcelain piece made for a young George III. Shortly after that, I was also able to acquire a dish made for King George III’s brother, the Duke of Gloucester. Christie’s January sale was a great resource for me and my next royal find was an ecuelle with the arms of France that may have been part of Louis XV’s porcelain used at Versailles (figs. 10, 11).[5] I fell in love with it, bit the bullet, and kept my paddle raised until it was mine! It now sits on a shelf with the British royals, and they look quite wonderful together.

While on another of my Winterthur tours in England, I was able to attend the Masterpiece Antiques show in London where I came across another one of my “must have” pieces. It was a cup and saucer decorated with the image of a Dutch East India Company 1728 coin in bold pinks and yellows (figs. 12, 13).[6] I had never seen them for sale, but they were fully priced and I was not sure I could afford them. After much contemplation, I knew that I would be haunted by those pieces if I did not buy them, so I did. Once I had them home and on the shelf with their peers, I loved them so much that I bought a dish from the same service when it became available a few years later.

By this time I had decided to try to add only exceptional pieces. When I had first started collecting, I bought some pieces from well-known services that I thought should be represented in my collection. When I realized that I wanted only the best examples, I decided I would try to upgrade if possible. For examle, early in my collecting I had purchased a piece from the beautiful 1730 Elwick service (fig. 14).[7] It was mostly grisaille with gilt highlights, and I was pleased with it—until I saw a piece for sale from the same service that had survived in better condition. The bodies of the two pieces were the same, but the new piece had beautifully crisp and bright enameling. Through my association with the Winter Show Circle, I had a friend who was interested in my original piece, so I was able to sell her my first piece and then upgrade to the brighter version. It was a win-win for all.

In New York City every January there is Antiques Week, a must for any antique collector. There are several different antiques shows around the city, among them the Ceramics Fair and Winter Show, and sales at Sotheby’s and Christie’s. The Chinese Export sale at Christie’s has long been the highlight of my collecting year. I head up there for four or five days and try to see everything. If I am lucky, I am also able to buy a few wonderful things. Since I had decided that I need to add different shapes and forms to my collection, I was delighted to find a large pair of covered armorial jugs with the arms of Mawbey impaling Pratt ordered circa 1766 (figs. 15, 16).[8] Although I had planned to purchase earlier items, this pair was so striking that I did not worry about their precise date of manufacture. I knew they would be a tremendous addition to my collection, and in retrospect I believe I was correct.

As a much younger collector I had seen and coveted a beautiful armorial dish with the arms of Haldane of Gleneagles, Scotland (fig. 17). Unfortunately, I did not have the money at that time, so I did not bid on it. The dish was not only a beautiful object, but was also a wonderful example of a mistake made by a Chinese artist. In order to ensure that the Chinese artists properly drew the family’s coat of arms, the family had sent along one of their bookplates. The artist did a beautiful job of copying, but mistakenly included the printed border. That mistake makes pieces from this service much more desirable than those with no errors.[9]

Years later, when another piece from this service appeared in Christie’s annual January sale, I was determined to obtain it, no matter what! I asked my good friend and dealer Henry Moog to bid on it for me, as I was scheduled to attend a board meeting that morning. I set a high limit to ensure that I would be the high bidder. The morning of the sale, however, I decided to miss my meeting just in case my high bid was insufficient, and I was quite happy I had done so since the bidding had quickly risen to my limit. I surveyed the room and found the culprit. It seemed that one of my collector friends was also interested in my charger. Henry pointed out that we were no longer the high bidders. In a split second I leaned over and told him that I did not care how much it would take, we were going to buy it! Fortunately, my friend quit bidding after just a few more bids and I was the lucky winner. Now, years later, I cannot recall how much I ultimately paid for it and it really does not matter. I have the pleasure of looking at this wonderful piece every day, and every day I chuckle about beating out my friend for this beautiful object.

As my collection grew and people started to come and see it, I wanted to share interesting stories about the different pieces. Early on I had acquired a few pieces from the Skinner family of 1728 and then realized that one of their friends, the Tower family, had ordered their family service at the same time. As early services, both were exquisitely painted, and identical except for the crests and the coats of arms. I felt that by adding a few pieces of the Tower service and displaying them together, they made a great little story (fig. 18).[10]

To every rule there is an exception, especially if it involves a great object. One day Henry Moog called me and said that he had just acquired a beautiful circa 1745 Scotsman bowl with a kilted private and bagpiper on the exterior and an image of Bonnie Prince Charlie in the interior (figs. 19, 20).[11] Although technically not an armorial, it was such a great object I felt that I had to add it to my collection. It also had a few hairline cracks which had been sealed, so I briefly hesitated because it was not perfect. However, I realized that this beautiful bowl would be such a positive addition to my collection that I had to have it. I am so glad that I decided to purchase it flaws and all!

Every serious collector must have a “hit list” of pieces they hope to add to their collection. Great objects are out there, but of course one must be prepared to pay more for the best. Acquiring the very best has been my goal all along, but when I first began I had a tiny budget and almost every “deal” in which I was involved turned out to be a matter of acquiring something with issues, especially if it were not expensive. I fully realized from then on that all new acquisitions had to be in the best possible condition, both structurally and decoratively.

One thing that draws me to an armorial piece of porcelain is the overall design incorporating the family coat of arms. The Krueger service for the Austrian market circa 1740 is, in my opinion, one of the better examples (fig. 21).[12] I was so taken with this service that over several years I was able to purchase a beautiful charger and a large coffeepot. As with many

of these special-order services, the pieces were made in Jingdezhen and decorated in Guangzhou, which was known to Europeans and Americans as Canton.

I have been asked many times which of the Chinese export pieces in my collection I covet the most. If I were forced to pick, I believe that it would be the soup plate with the arms of Van Hardenbroeck, made about 1734 (fig. 22).[13] It is very thinly potted and beautifully painted, and to me it epitomizes the quality of the porcelain and the care in the enameling that took place during the reign of Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1722–1735). It is as light as a feather, and it is beautiful. If the house caught fire, I think this would be the one piece I would be sure to carry out with me.

After many years of collecting, I finally decided to listen to the best dealers and collectors and buy only the finest objects in the best condition. As a fine-art insurance specialist for four decades now, I find that most of our clients who were “price buyers” wound up with mediocre collections that they believed had great value. Unfortunately, when their coveted objects were sold, they or their descendants were almost always disappointed with the results. Knowing this, I decided to improve my collection by including only the best possible examples.

My real “sweet spot” are pieces from the 1730s and one of my very favorite armorial services from that period is the 1733 Lee of Coton (fig. 23).[14] As a graduate of Washington and Lee, I very much wanted a piece of this well-known service, especially since it boldly featured the arms of the Lee family. My first piece was obtained from a dealer friend who convinced me to buy it even though it had some restoration. Once I got it home, I realized it was more extensively restored than I had been told. I kept trying to love it, but I just could not. So, I sold it at a loss. Fortunately, a few years later my friends at Christie’s offered a beautiful example from the same service in excellent condition and I was able to buy it. It sits in the same place as its predecessor, but now I do not have to apologize for it.

Years ago, one of the great American collectors Bill du Pont asked me if I owed anybody any money. I quickly responded that in fact I owed money to several people, all antiques dealers. He laughed, shook my hand, and said “Congratulations. You really are a collector.” He went on to say that true collectors are always looking for the next great thing, even before they have finished paying for the last one. Like Bill, I have found that my favorite items are the ones I will find tomorrow!

In closing, I would advise you to try to learn as much as you can about the area you collect. I encourage you to join wonderful groups like the American Ceramic Circle and the Decorative Arts Trust, and go to their fun, informative meetings and lectures and tour. Equally important, you should also visit and join the museums and historical societies that may collect the same things that you do. The rewards are endless.

David Sanctuary Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain (London: Faber, 1974), p. 717.

John Sandon, The Ewers-Tyne Collection of Worcester Porcelain at Cheekwood (Woodbridge, Eng.: Antique Collectors’ Club, 2008), pp. 98–99.

Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain, p. 176.

Ibid., pp. 184, 404.

Antoine Lebel, French and Swiss Armorials on Chinese Export Porcelain of the 18th Century (Bruxelles: Antoine Lebel, 2009), pp. 18–19.

Zhangshen Lü, ed., Passion for Porcelain: Masterpieces of Ceramics from the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum (Beijing: Zhonghua shu ju, 2012), pp. 100–101.

Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain, p. 234.

Ibid., p. 614.

David Sanctuary Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain Volume II (Chippenham, Eng.: Heirloom & Howard Ltd., 2003), p. 131.

Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain, pp. 170–71.

Ronald W. Fuchs II, Made in China: Export Porcelain from the Leo and Doris Hodroff Collection at Winterthur (Winterthur, Del.: Henry Francis DuPont Winterthur Museum, 2005), pp. 132–33; Zhangshen Lü, Passion for Porcelain, pp. 150–51; William R. Sargent, Treasures of Chinese Export Ceramics from the Peabody Essex Museum (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), pp. 322–23.

David Sanctuary Howard and John Ayers, China for the West: Chinese Porcelain & Other Decorative Arts for Export Illustrated from the Mottahedeh Collection (London: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1978), p. 454.

Jochem Kroes, Chinese Armorial Porcelain for the Dutch Market (Zwolle: Waanders, 2007), pp. 259–60.

Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain, p. 329.