A portion of the Bruce Coleman Perkins Collection on display in his home.

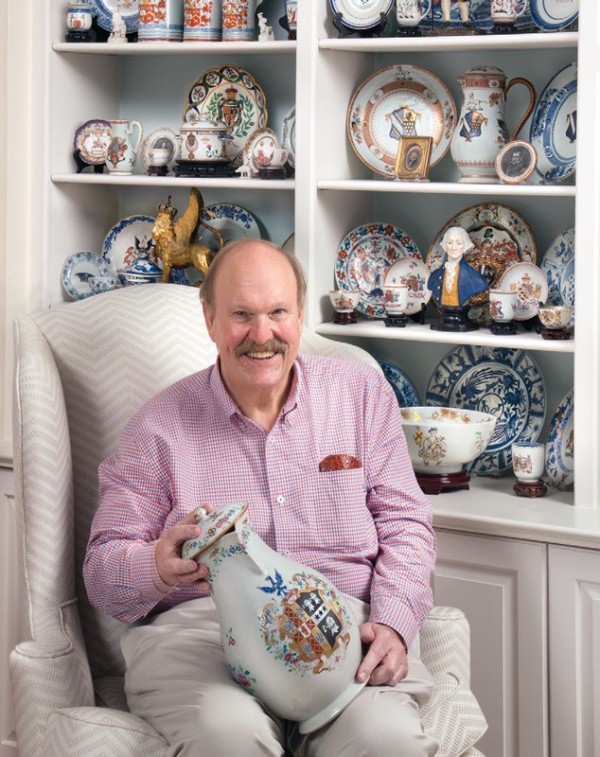

The collector with one of his favorite pieces.

Tureen, made in Jingdezhen and decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, 1820–1825. Hard-paste porcelain. L. 13 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This tureen, decorated in the Fitzhugh pattern, is from a service that belonged to Charles Irénée

du Pont (1797–1869) and his wife, Dorcas van Dyke (1806–1838). They married in 1824 and the service is thought to have been a wedding gift.

Plate with the arms of Cutler, made in Jingdezhen and decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, ca. 1790. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 9 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This plate is from a service made for Henry Cutler of Sidmouth, England, who married Katherine Olive in 1788. The service may have been made to celebrate their wedding.

Mugs with the arms of Gough impaling Hynde, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1720. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 6 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These three mugs are decorated in the Imari palette of underglaze blue and overglaze red and gold. They are from one of the four Chinese armorial porcelain services that were made for Harry Gough (1681–1751) and his wife, Elizabeth Hynde (1699–1774). Gough spent his career working for the East India Company, which gave him the wealth and connections needed to commission armorial porcelain.

Plate with the arms of the Duke of Clarence, Flight’s Worcester Porcelain Factory, Worcester, England, ca. 1789. Soft-paste porcelain. D. 10". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This plate, which comes from the first royal armorial service made at Worcester, was commissioned by William Henry, Duke of Clarence and Saint Andrew, who later became King William IV of Great Britain and King of Hanover (1765–1837). It was made to celebrate his elevation to the Dukedom of Clarence and Saint Andrew in 1789.

Charger with the arms of Pitt, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1705. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 14 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This charger is from a service made for the China trade merchant Thomas Pitt (1653–1726. Pitt’s wealth helped establish a political dynasty that included two prime ministers: his grandson William Pitt the Elder (1707–1778) and his great-grandson William Pitt the Younger (1759–1806).

Plate with the arms of Pitt with Ridgeway in pretence, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1720. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 8 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This plate is from a service made for Thomas Pitt, Baron (later Earl) of Londonderry, and Frances Ridgeway, who married in 1718. Frances had no brothers, meaning she would inherit her father’s estates, which is shown by her arms being placed on a small shield “in pretence” or on top of her husband’s shield.

Plate with the arms of Pitt impaling Grenville, made in Jingdezhen and decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, ca. 1772. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 8 7/8". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The service from which this plate comes was a gift from the British East India Company to William Pitt the Elder (1707–1778), Great Britain’s first prime minister, and his wife, Hester Grenville, Viscountess Cobham (1720–1803).

Ecuelle with arms of France, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1725. Hard-paste porcelain. L. 6 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This ecuelle, or covered bowl, is from a large service possibly made for Louis XV (1710–1774), king of France.

Detail of the ecuelle illustrated in fig. 10.

Plate, teabowl, and saucer with monogram of the VOC, made in Jingdezhen, China, 1728–1730. Hard-paste porcelain. D. of plate 9". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These pieces are decorated with the arms of the Dutch Republic with the motto Concordia res parvae crescent (through unity small things become greater). The design is copied from a silver ducatoon, a coin struck for use by the Verenigde Oost-indische Compagnie, or Dutch East India Company, in Asia. The monogram of the VOC is painted in the interior of the cup.

Interior of the teabowl illustrated in fig. 12.

Soup plate with the arms of Elwick, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1730. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 8 1/2". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Combining an English coat of arms with a Chinese landscape scene, this soup plate comes from a service made for John Elwick (d. 1730) of London. Like many people who commissioned armorial porcelain in the first half of the eighteenth century, John had links with the China Trade, serving as a director of the East India Company.

Jug with the arms of Mawbey impaling Pratt, made in Jingdezhen and decorated in Guangzhou (Canton), China, ca. 1766. Hard-paste porcelain. H. 15". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This massive beer jug, one of a pair, was made for Sir Joseph Mawbey (1730–1798), an English distiller and member of Parliament and his wife, Elizabeth Pratt (d. 1790).

Detail of the arms on the jug illustrated in fig. 15.

Charger with the arms of Haldane, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1725. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 14". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This charger was part of a service made for a member of the Haldane family of Gleneagles, Scotland. Like many armorial services, the coat of arms is copied from a bookplate. Bookplates were a convenient way of sending an image of one’s arms to China to be copied, but in this, one of the earliest known uses of a bookplate as a design source, no one provided instructions that the printed border was not to be copied.

Coffee cup and saucer with the arms of Tower, and coffee cup and saucer with the arms of Skinner, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1730. Hard-paste porcelain. Saucer D. 4 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These two cups and saucers, which match except for the coat of arms, were commissioned at the same time and most likely were decorated in the same workshop. The one on the left was made for either Christopher Tower (1694–1771) or Thomas Tower (1698–1778), brothers who served as lawyers, politicians, and as trustees of the Colony of Georgia. The one on the right was made for Matthew Skinner (1689–1749), a sergeant at arms, judge, and member of Parliament.

Punch bowl, Jingdezhen, China, 1743–1750. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 11 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Probably made for a Jacobite sympathizer—someone who supported the deposed Stuart dynasty of England, Ireland, and Scotland—the exterior of this bowl is decorated with a Scottish private and piper (seen here) from the First Highland Regiment of the British army. The image of the piper is based on the frontispiece of A Short History of the Highland Regiment, published in London in 1743, which was also sold as an individual print. Drinking toasts to the exiled Stuarts was a popular way for Jacobites to show their support, and wine glasses, beer mugs, and punch bowls with Jacobite imagery were made to facilitate those rituals.

Punch bowl, Jingdezhen, China, 1743–1750. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 11 3/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Probably made for a Jacobite sympathizer—someone who supported the deposed Stuart dynasty of England, Ireland, and Scotland—the exterior of this bowl is decorated with a Scottish private and piper (seen here) from the First Highland Regiment of the British army. The image of the piper is based on the frontispiece of A Short History of the Highland Regiment, published in London in 1743, which was also sold as an individual print. Drinking toasts to the exiled Stuarts was a popular way for Jacobites to show their support, and wine glasses, beer mugs, and punch bowls with Jacobite imagery were made to facilitate those rituals.

Detail of the interior of the punch bowl illustrated in fig. 19. (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Within the bowl is a portrait of Charles Edward Stuart (1720–1788), popularly known as Bonnie Prince Charlie. The grandson of King James, the deposed king of England and Scotland, he claimed the throne of Great Britain. In 1745 he led an invasion of Britain that came close to succeeding; he gathered supporters in Scotland and led an army as far south as Derby in England before retreating back into Scotland, where he was defeated at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. He remained in exile in Europe for the rest of his life.

Charger and coffeepot with the arms of Krueger,made in Jingdezhen and decorated in Guangzhou (Canton),China,ca. 1740. D. of charger 15 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) These pices are decorated with an elaborate Continental European armorial, probably that of Krueger family of Austria.

Soup plate with the arms of Van Hardenbroeck, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1734. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 8 1/4". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This eggshell-thin soup or dessert plate was probably made for Johann Louis van Hardenbroeck (1691–1747), a ship’s captain who served in the Admiralty of Amsterdam and later as a member of the States-General, the governing body of the Netherlands

Plate with the arms of Lee, made in Jingdezhen, China, ca. 1733. Hard-paste porcelain. D. 9". (Photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Much of the armorial porcelain illustrated in this article would have gone through the two ports—London and Guangzhou (Canton)—painted on the rim of this plate. In the center is the arms of the Lee family of Coton, England. The Lees of Virginia, including Robert E. Lee, one of the namesakes of Washington and Lee University, used these arms from the time they arrived in Virginia in the seventeenth century.