David Stuempfle at his kiln during a firing in the spring of 2016. (Unless otherwise noted, all photos by Robert Hunter.)

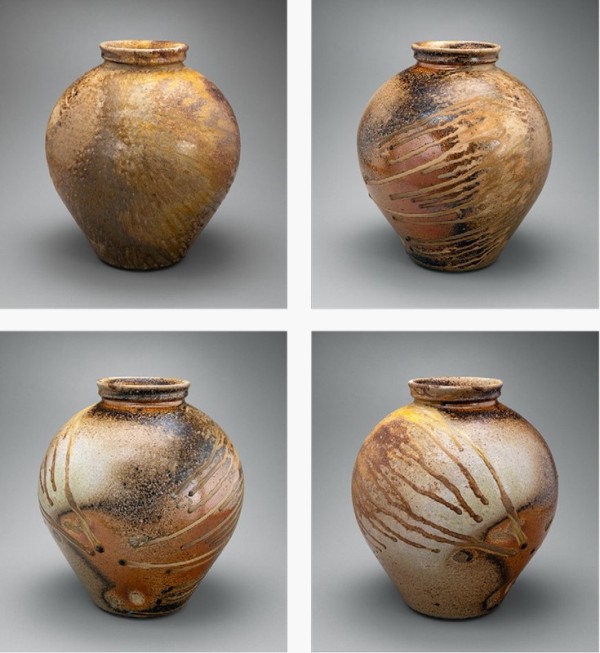

“Chinese” jar, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2016. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 34". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the jar illustrated in fig. 2.

Storage jar, Shigaraki Valley region, Japan, Muromachi period

(1392–1573). Stoneware with natural ash glaze. H. 18 3/8”. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard, and Purchase, Fletcher, Rogers, Harris Brisbane Dick, and Louis V. Bell Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, 1975.)

Onggi jar, Oh Hyang Jong, David Stuempfle Pottery, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2001. Wood-fired stoneware. H. 60". (David Stuempfle collection) This massive jar was made by a visiting South Korean artist and fired in David’s kiln. Oh Hyang Jong came to Seagrove three or four times in the early 2000s and often brought other Korean artists with him.

Map showing the location of the town of Seagrove within Randolph County in North Carolina’s Piedmont (Map, Wynne Patterson.)

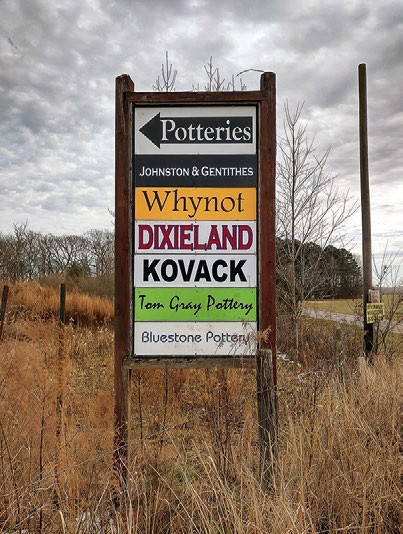

Highways signs in Seagrove,

at exit 45 off i-73/i-74. (Photo, Lindsey Lambert.) North Carolina Highway NC 705 is designated as the Pottery Highway or Pottery Road, and is a registered North Carolina Scenic Byway.

Signs seen along the Pottery Highway at nearly every crossroads direct visitors to the many potteries that dot the landscape. (Photo, Lindsey Lambert.)

David Stuempfle’s kiln shed and potting workshop during a firing in 2016.

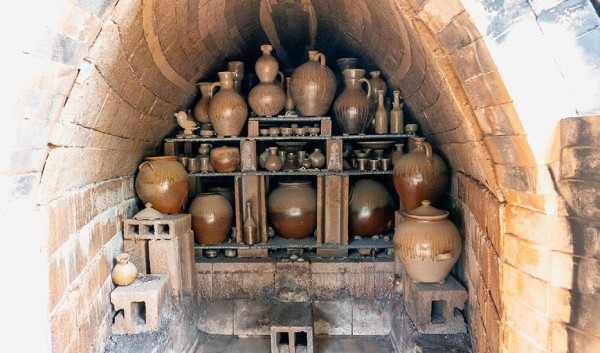

Groundhog kiln being fired at the North Carolina Pottery Center, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2016. This working kiln is used for demonstrating the wood-firing process. The firing takes approximately fifteen hours and requires two cords of wood.

David Stuempfle at a firing of the groundhog kiln at the North Carolina Pottery Center, Seagrove, 2016. The single doorway facilitates both loading the ware and stoking the kiln.

Michelle Erickson unloads a fired pot through the narrow door of the groundhog kiln at the North Carolina Pottery Center, 2016.

Nancy Gottovi with bloodhound friend, 2016.

Nancy Gottovi opening a side port to the kiln during a firing in May 2016.

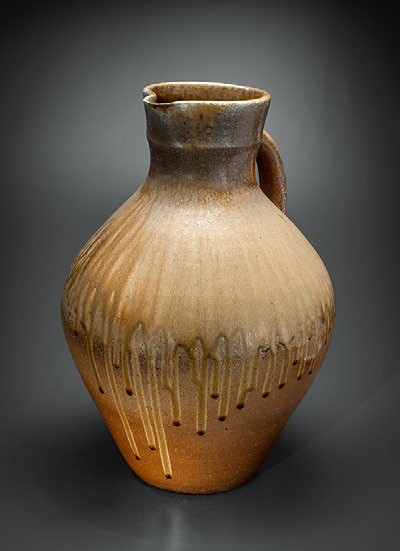

Pitcher, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 1995. Salt-glazed stoneware with applied ash glaze. H. 14". (Private collection.) The tapering cylindrical form of this tall pitcher is reminiscent of English medieval pottery. The ash encrustation is the result of being buried in the kiln’s ember pile.

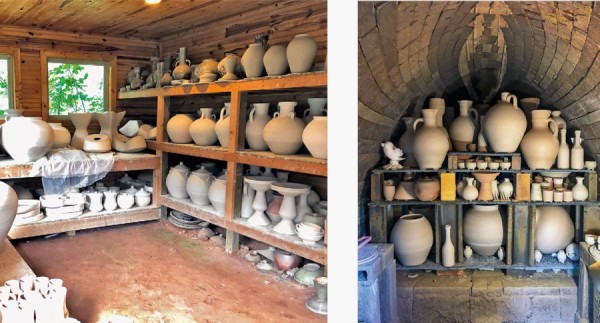

Greenware drying on the shelves in David Stuempfle's workshop (left) and arranged on the shelves of the kiln during loading (right). (Photos, Michelle Erickson.)

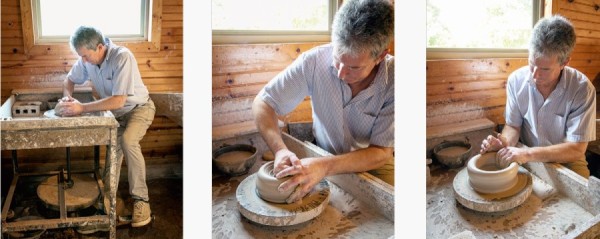

Throwing on a traditional treadle wheel. For his small work, what he calls “tableware,” David uses this foot-powered wheel to raise his vessels.

A flower pot being raised on the treadle wheel.

Drawing, Kim Jun-Geun (Kisan) (Korean, 1850/1950), Korea, ca. 1880–1890. (© British Library Board, acc. no. 14344.) This nineteenth-century drawing shows an onggi potter raising a jar on a treadle wheel using a wooden paddle and an anvil to stretch and shape the pot.

Large ropes or coils of clay are formed and rolled by hand.

The coil is attached to the rim of the pot and thumbed into the wall of the pot.

The coil is further worked by hand into the wall of the pot.

The pot is slowly rotated as the attached coil is compressed using a series of carved paddles. A wooden “anvil” is used to compress the interior wall during this process (see fig. 19).

A wooden rib helps shape the final contours of the body.

Using a propane torch, the newly applied and shaped section must dry for several minutes to stiffen the wall before the next coil can be applied.

After the final form of the vessel is achieved, the rim is shaped and handles are applied.

A group of greenware pots dry in the shop before being loaded into the kiln for firing.

A large Han-style jar with glass runs being removed from David Stuempfle’s kiln by Owen Laurion as Rose Hardesty awaits her turn to enter the kiln.

The large kiln during firing in 2016.

Seagrove potter Chad Brown during the loading of greenware into the kiln. Note the use of shelves to create layers of firing space. (Photo, Michelle Erickson.)

Stoking the main firebox. Access holes beneath the door allow venting of the kiln to remove excess cinders and ash during firing.

Seagrove potter Takuro Shibata stokes one of the side ports.

Storage jar, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2020. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 15". (Private collection.) This ovoid jar was placed on its side on the kiln floor, which allowed ash to accumulate on the side facing up, creating dramatic runs from the melted wood ash.

An electronic digital pyrometer is used to monitor the temperature inside the kiln. The temperature is gradually increased over the four- or five-day firing period until the kiln reaches its peak temperature, about 2435 °F.

A series of pyrometric “cones” are placed in the firing chamber to gauge when sufficient temperature has been achieved. The cones will bend to indicate temperatures between Cone 12 (2435 °F) in the front of the kiln and Cone 10 (2381 °F) in the back.

The color and quality of the flames as observed through the firebox are additional indicators of temperature and the amount of carbon contained in the atmosphere. Protective eyewear is essential.

The first view of the fired kiln immediately after opening.

Seagrove ceramic artist Fred Johnston works with David to remove a large storage jar from the kiln using a bedsheet sling. (Photo, Michelle Erickson.)

First view of a large jug/bottle as it emerges from the kiln. Often pots are extremely warm at this stage, necessitating insulated gloves to carry them.

The still-warm pots are systematically laid out on the lawn adjacent to the kiln.

David emerges from the kiln carrying a large jar.

David closely inspects the base of a large jar.

Michelle Erickson and David Stuempfle assess a group of wares.

Stillman Browning-Howe, a regular member of David’s firing team, inspects a jar after it has emerged from the kiln. The circular marks on the bottom are from the wadding spacers.

Anne Pärtna (left) examines a bowl removed from the kiln. Anne is a native Estonian and has her own ceramic practice in Seagrove but often fires some of her larger works (right) in David’s kiln.

Michelle Erickson showing two of her stoneware jugs fired in David’s kiln in 2019.

A 2020 firing and kiln unloading crew during times of Covid 19. Left to right: Stillman Browning-Howe, Hamish Jackson, Miki Palchick, John Freeman, David Stuempfle, and Michelle Erickson.

A selection of vessel forms just unloaded from the 2020 firing of David Stuempfle’s kiln.

David examines one of his traditional pitcher forms immediately after it was unloaded from a kiln firing.

Ovoid pitcher, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2016. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 19". (Private collection.)

Medieval pitcher, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2018. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 18". (William C. and Susan S. Mariner Collection.)

Storage jars, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2015. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/2“. (Private collection.) Two ovoid storage jars as they appear immediately after firing, with well‑developed wood-ash glaze and carbon deposits.

Storage jars, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2019. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 24". (Private collection.)

Jar, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2018. Slip and ash-glazed stoneware. H. 25". (Asheville Art Museum; Gift of Robert Williams in memory of Warren Womble, 2020.17.02. © David Stuempfle.)

Two-handle jug, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2018. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 24". (Private collection; photo, Jason Dowdle.)

Gourd-shaped vase, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2016. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 20". (Private collection; photo, Jason Dowdle.)

Pedestal bowl, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2018. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 12". (Private collection; photo, Jason Dowdle.)

Stemmed bowl, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2016. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 9" (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Stirrup vessel, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2017. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/2. -(Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Storage jar, Thomas Chandler, Edgefield County, South Carolina, 1840–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16 3/8“. (William C. and Susan S. Mariner Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This large jar is embellished with Chandler’s distinctive two-color

slip-decorated swag design.

Syrup jug, Thomas Chandler, Edgefield County, South Carolina,

1840–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16 3/8“. Mark: “CHANDLER / MAKER” (Private collection.) This classically shaped jug is embellished with a white slip-decorated design.

Detail of storage jar, Thomas Chandler, Edgefield County, South Carolina, 1840–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16 1/2“. (The Joseph P. Gromacki Collection.)

Detail of storage jar, Frederick Carpenter, Little Brothers Pottery, Charlestown, Massachusetts, ca. 1800–1810. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/2“. (The Joseph P. Gromacki Collection.)

Storage jug, Frederick Carpenter, Charlestown, Massachusetts, ca. 1812–1827. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16". Impressed with three hearts, indicating three gallons. (The Chapman Collection.) This jug is illustrated in Mark Hewitt and Nancy Sweezy, The Potter’s Eye: Art and Tradition in North Carolina Pottery (Chapel Hill: Published for the North Carolina Museum of Art by the University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

David Stuempfle examines a three-gallon jug from his collection, made by Frederick Carpenter in Charlestown, Massachusetts, ca. 1812–1827.

Jug, David Drake, Lewis J. Miles Pottery, Edgefield County, South Carolina, ca. 1850s. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 17". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; 1939-137.)

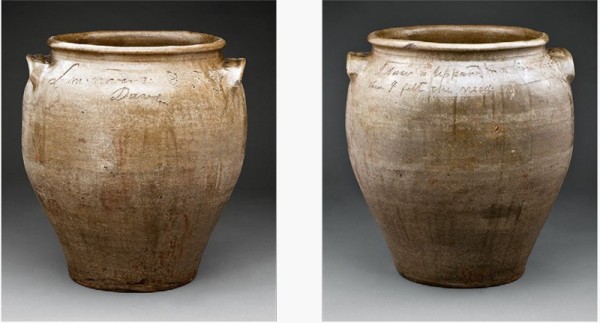

Storage jar, David Drake (1800–ca. 1873), Edgefield County, South Carolina, dated 1858. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 24 1/4.” (Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, MESDA Purchase Fund, 4317.) One side of this jar is inscribed “L.m. nover 3, 1858 / Dave.” The other is marked “I saw a leopard & a lions face/ then I felt the need—of grace,” an adaptation from the Book of Revelation.

Storage jar, Daniel Seagle, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 19 3/4 Stamped twice: DS (Private collection.) This storage jar holds 16 gallons.

Storage jug, Daniel Seagle, Lincoln County, North Carolina, 1830–1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16". (Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; Loan courtesy of Beverly Owens Jaynes.)

Storage jar, Isaac Lefever, Lincoln County, North Carolina, 1850–1860. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16". (William C. and Susan S. Mariner Foundation.)

Jug, attributed to Edward Webster, Fayetteville, North Carolina, 1820–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16 1/2“. (William C. and Susan S. Mariner Foundation; photo, Crocker Farm, Inc.)

Storage jar, Chester Webster, Randolph County, North Carolina, dated 1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/8“. (Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the jar illustrated in fig. 72.

Michelle Erickson stokes the kiln with slabs while firing crew Bill and Susan Mariner wait their turn. Potter Matt Levy looks on.

David emerges from the kiln with one of his signature gourd-shaped vases.

A group of gourd-shaped vases in the workshop awaiting sale.

David and Josephine with an assortment of his ash-glazed stonewares after a kiln firing in 2019.

My work is at the intersection of traditional art and contemporary studio pottery. I have been influenced by extensive travel in Europe and Asia, and by studying historical and contemporary American pottery in order to create work that is unique to me. Using local clays and firing with wood connects me to the geology and ceramic culture of the area. [1]

—David Stuempfle

One of the most ancient man-made magical acts is the transformation of raw clay into something useful, beautiful, and permanent through the transformative agency of fire. This potter’s trick has been appropriated by many cultural groups throughout the world to represent a metaphor for the supernatural creation of the human race. Requiring little more than the clay, water, and fuel for a fire, prehistoric potters created vessels for food preservation, preparation, even burial receptacles, and they intertwined the craft with aesthetic choices that makes ceramics among the oldest of mankind’s art objects. Today, a devoted worldwide community of acolytes keeps the fires burning, thus preserving the art and mystery of wood-fired stoneware.[2] This article features the work of one such devotee, stoneware potter David Stuempfle, whose practice is ensconced in the small North Carolina town of Seagrove (fig. 1).

David is a central pillar of the Seagrove ceramics community of just over two hundred residents. His own ceramics practice transcends both time and space, channeling the historical stonewares of Great Britain, Germany, and the eastern United States and the ash-glazed stonewares made in China, Japan, and Korea (figs. 2, 3). His strong, at times imperceptibly irregular forms with their otherworldly, volcanic glazes—born of fire and ash—can be described using the same poetic language used by connoisseurs of Japanese stoneware from the traditional ash-glazed kilns of the Shigaraki Valley region (fig. 4).[3] David worked in one of those very kilns in 1998.

Beyond his mastery of form and material, David is an energetic educator and advocate for the tradition. He lectures widely and provides intimate demonstrations of his monumental jar making throughout America. He is active in the North Carolina Pottery Center where, as exhibitions chair, he has curated several exhibits. David was a principal organizer of the 2017 International Wood Fire Conference held at STARworks in Star, North Carolina, where invited ceramic artists and speakers from across the globe came to discuss all aspects of the craft.[4] Most recently he curated an exhibition for North Carolina’s Mint Museum devoted to world pottery traditions.[5]

David’s ceramics have been featured in numerous articles and books.[6] His work can be found in major museum and private collections throughout the United States and abroad—the Mint Museum of Craft and Design, the Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park Museum (Japan), the Museum of American Ceramic Art, the Mobile Museum of Art, the Fuller Craft Museum, the Asheville Museum of Art, the Chipstone Foundation, and the Museum of International Folk Art, among others. He has traveled through Europe, and worked in Estonia, Japan, and South Korea to learn from other working potters, absorbing and adapting the intricacies of his international colleagues’ techniques. Those investments in travel have been reciprocated many times over as international potters from Canada, England, Estonia, Finland, Japan, Mexico, Russia, South Korea, Sweden, and Taiwan have made pilgrimages to David’s workshop and kiln (fig. 5).

Seagrove

The history of ceramics making runs deep in North Carolina. Native Americans were making pottery for nearly three thousand years in many parts of the region, and European arrivals have been supplying local communities with their pots and pans since the eighteenth century. Among the better-known traditions are the Moravian potters of Bethabara and Salem, who started producing utilitarian and decorative earthenware in 1754 for those newly formed piedmont communities.[7] Other Germanic and Quaker immigrants also brought their ceramics traditions to newly settled communities through North Carolina’s Piedmont.[8] Smaller-scale potters have worked in the greater Seagrove area since the eighteenth century, taking advantage of widespread deposits of native clays and stands of timber (fig. 6). Much of the early ceramic history of the area has yet to be written, but these earliest potters produced lead-glazed earthenware with the red clays and (later) salt-glazed stoneware in the mid-nineteenth century using the higher-firing white and gray clays.

For much of its preindustrial past, most Seagrove area potters were farmers who seasonally produced utilitarian jars and jugs that were sold in the extended community. But in 1895 a full-time pottery shop was established by James H. Owen, still in operation and often called “the oldest, continuously operating pottery in North Carolina,” now owned and operated by sixth-generation descendant Boyd Owens. It was the establishment in 1917 of the Jugtown pottery by Jacques and Juliana Busbee from nearby Raleigh, North Carolina, however, that put Seagrove on the map. Its founding marked the modern history of ceramics-making in Seagrove and brought national recognition to the area’s long-standing ceramics tradition.[9] Most important, the launch of Jugtown began to attract other ceramicists to the Seagrove area who shared a love of the traditional methods. Those newly arrived potters augmented the area’s multi-generation family dynasties whose surnames include Albright, Auman, Cole, Craven, Owens, and Teague.[10]

Although the tradition of making functional wares continued, the twentieth century brought a shift toward more artistic innovation, with new designs, shapes, and highly decorative glazes.[11] These so-called art wares were initially marketed to resorts and gifts shops, but by the 1950s tourists and collectors were making regular visits to Seagrove potters, whose wares began to enjoy national attention. While the potters themselves maintained fierce independence, guarding their designs and glaze secrets, they formed alliances to establish community-wide sales and exhibitions to promote their works.

Today a single stoplight greets both casual tourists and serious ceramics collectors from across the country as they exit i-74 to explore the more than eighty working potteries in a twenty-mile radius. The State of North Carolina has designated the primary route through Seagrove and its environs as “Pottery Highway” or “Pottery Road,” and it is recognized as a North Carolina Scenic Byway (fig. 7). The greater Seagrove community is sprawled across the rural landscape, linked by a spiderweb of country roads. As one drives through the modest farmlands, potteries with signs just large enough to identify the owners dot the scenery.

At almost every crossroads is a cluster of signs pointing to a half dozen of the area’s potteries (fig. 8). Paradoxically, but in keeping with David’s low-key temperament, no sign marks the Stuempfle pottery on Dover Church Road; unless you knew his entrance to the property was just opposite the volunteer fire department, you would never find it. Once you turn onto the narrow but well-maintained gravel driveway, it is another quarter-mile drive before the umber-stained frame house, workshop, and kiln shed rise up in a meadow (fig. 9).

Background

David was pre-adapted to the life of a potter. Born and raised in rural Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by socially progressive parents, Herman and Gretchen Stuempfle, he was encouraged in the arts and came to pottery making in the New England boarding-school experience of the High Mowing School, a private, independent school whose curriculum is based on “Waldorf education,” founded by the Austrian philosopher and scientist Rudolf Steiner, and is designed to develop pupils’ intellectual, artistic, and practical skills in an integrated and holistic manner.[12] Underpinning the teaching method is an emphasis on rhythm:

Human life is filled with rhythms. They play an essential role in all life processes and in processes of cognition as well. Every rhythmical exchange is at the same time a process of transformation. The air we breathe out is quite different from that which we breathe in. We can discover such moments of transformation in the child’s learning. When writing, we no longer think of the struggles we had to learn the individual letters [sic]. All this has been forgotten and becomes the ability to write. This rhythm of remembering and forgetting can be used consciously by teachers to support the child’s learning. Waldorf education strives to support these processes not only through rhythm in movement, but also through teaching methods which take the rhythmical nature of learning into account.[13]

In this setting, David was mentored by the iconoclastic ceramic teacher Isobel Karl, a 1945 graduate of Alfred University’s celebrated ceramics program. She has taught many students who have gone on to become highly successful ceramic artists, and while she had many students who studied ceramics in academia, she was open to other ways of learning as well. Karl introduced David to the possibility of apprenticeship and journeymanship as an alternative to a university program.

The jumping-off point for David’s professional journey began with a two-year apprenticeship with potter Lewis Snyder, a master potter and director of the Crafts Division of the Tennessee Arts Commission in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. During his six-days-a-week training, David learned the workings of the trade from Snyder. This early internship exposed David to all aspects of the pottery business, from sweeping floors to the selling of the wares. Perhaps most important, being instrumental in the International Ceramic Symposium, Snyder exposed David to working ceramics artists from around the world. A telling quote from a 1972 interview with Snyder, “Pottery is a sharing and learning-from-each-other art,” also pervades David’s philosophy of his own practice.[14]

From the creative hive of Snyder’s Tennessee studio, David took on the life of a journeyman production potter, which included a four-year stint in several of Wisconsin’s ceramics factories, among them the large-scale potteries Rowe Pottery and Rockdale Union in Cambridge. At that time, in the 1980s, there was great interest in the public eye for collecting historic American stoneware, and both of those large firms made and marketed museum-quality reproductions of cobalt-decorated salt-glazed jars and jugs. For David it was, in addition to gainful employment, an opportunity to develop his throwing skills through the daily repetition and rhythms of making vessels to exacting sizes and shapes. Furthermore, he says, this is where his interest in making larger pots was developed, as he was making “thirty- to forty- pound pots all day long.”[15] However, his tenure at the Wisconsin factories also convinced David that the life of a reproduction potter was not for him. He consciously endeavored to “look ahead” and seek his own artistic path, eschewing merely making other people’s pots.

David became aware of the Seagrove community in the mid-1980s, when he worked for a short period with Vernon Owens and his wife, Pam, at their historic Jugtown Pottery in Seagrove. Pam had grown up in New Hampshire and also had been a student of Isobel Karl at the High Mowing School. Looking for a more creative situation, David returned to Seagrove again in 1989 where he worked as a journeyman potter at Jugtown and at the late Melvin L[ee] Owens shop. He believed that if he was going to really learn about making pots in the American tradition, he had to understand the materials and methods of wood firing.

With prior experience limited to electric and gas kilns, David wanted to absorb the wood-firing technologies used by the Owens, a multigenerational Seagrove potting family that was immersed in the traditional methods of the craft.[16] Used by utilitarian potters in all parts of the South, the “groundhog” kiln was the de facto kiln design for much of Seagrove’s ceramics history (fig. 10). It is a low, semi-subterranean brick or stone structure with a firebox at one end and a chimney at the other for creating the draft (fig. 11). A single doorway facilitates the loading and unloading of the ware as well as the stoking the kiln with fuel (fig. 12). The Owenses fired their groundhog kilns dozens of time during the year, which gave David extensive experience in the varied properties of wood as a fuel.

As important, David studied the building and firing properties of the local clays, particularly the white firing clays from the Auman Clay Pond in the Michfield area of Seagrove.[17] When dug from the ground, these indigenous clays are a light grayish-blue color, but when fired to temperature they turn almost white.

David also perceived that while the Owenses were steeped in tradition, they pursued their personal visions of artistic expression with innovations in new forms, glazes, and designs. After being immersed in the process of matching materials to firing techniques, David brought with him a wealth of practical knowledge when he started his own practice.

In 1990 David bought twenty acres of undeveloped land to begin building both a dwelling and workshop. By 1992 his life partner, Nancy Gottovi (fig. 13), had joined him and has been integral to the workings of the pottery ever since. With a Ph.D. in cultural anthropology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Nancy oversees a large craft community of glass and ceramic artists as executive director of STARworks in nearby Star, North Carolina. Despite her busy career, Nancy helps David with firings, and oversees sales and promotions plus the business’s bookkeeping (fig. 14).

The first kiln David built was a highly modified, thirty-foot-long groundhog-type kiln for making salt-glazed ware. The pitcher illustrated in figure 15 is a product of that kiln.[18] The kiln remained in service until 2010, when David built a second kiln intended for only wood-ash firings. That second large kiln is a flame-shaped anagama—a design based on his research and experience in Asia—that he built with the help of Estonian kiln builder Andres Allik.[19] David added a small rectangular downdraft kiln in 2019, which he uses for periodic firings of smaller vessels.

Making Pots

For David, making pots is a solitary endeavor, and the formula for his production schedule is simple: build enough to fill the kiln, fire the kiln, sell the pots, repeat. Every step in the process has a rhythm, measured by time—the mixing of the clay, the turn of the wheel, the stoking of the kiln—so it is not surprising that David’s other passion is music, and he is an avid Irish uilleann piper. Like most Seagrove pottery shops, the majority of his pots are sold right at the kiln, usually immediately after its unloading. His current schedule is three firings a year.

David’s workshop often appears alarmingly empty, with a hard-packed clay floor and empty shelves and benches. He prefers to work in an austere room with lots of natural light. A lone pug mill, a machine for mixing and working raw clays, stands out as the only mechanized equipment in the shop, save a couple of floor lamps and a muddy radio. Only when he is building do the raw materials of his craft become visible in the shop. The search for local clays is part of the balance of achieving both functional and aesthetic success. For the most part, he continues to use Seagrove’s Michfield fire clay, Cameron ball clay, and Okeeweemee red clay mixed with commercial clays, grog, and feldspar. Takuro Shibata, who oversees the STARworks clay business, makes David’s custom clay bodies, and David is constantly experimenting with new clay mixtures in his studio.[20]

Although David sketches regularly and keeps notebooks for clay and glaze recipes, kiln-firing schedules and other information are kept out of sight in the work areas. The template for every form seems to be etched in his mind, his eye, and the muscle memory of his arms and hands. The constraints of the kiln chamber are the guiding concern as to what sizes and shapes David creates for each firing. A half dozen massive jars for the central spaces are augmented with perhaps two dozen jars and pitchers in the five- to ten-gallon ranges, and an assortment of gourd-shaped vases, flowerpots, bottles, and some smaller “tablewares” (fig. 16).

Throughout his career, David has developed a number of building techniques that are well suited to his interest in traditional shapes and larger forms. The smaller work is thrown on a traditional treadle wheel, the kind used by potters the world over since antiquity. As the name implies, the device relies on leg power to drive a heavy flywheel, which subsequently turns the wheel head. Unlike throwing on an electric wheel, the entire body engages in the kinetic rhythm of the treadle wheel (fig. 17). Clay forms are raised quickly with an economy of motion (fig. 18). For larger forms—jars, pitchers, and bottles that are up to twenty inches in height—David often joins together individually thrown wall sections which subsequently are shaped into final form on an electric wheel.

For his signature large vessels, David has adapted the techniques of the Korean onggi potters using a combination of coiling and wheel throwing.[21] Onggi was an important part of Korea’s traditional culture, providing large storage jars for making fermented foods, such as kimchi, gochujang (red chili paste), and makgeolli (rice wine).[22] The techniques of the onggi potters are used by a number of big-pot makers in both America and England (fig. 19).

David first prepares a wheel-thrown base for his large pots to which he adds successive coils of clay to build up the walls. The large coils are prepared by hand and rolled out on his bench (fig. 20). Then they are laid on the rim and attached by thumbing the coil into the body (fig. 21). The coil is further flattened by hand to consolidate the coil into the body (fig. 22).

Once a coil is firmly attached, the pot is slowly rotated on a wheel as the clay wall is beaten with a series of carved wooden paddles (fig. 23). A wooden “anvil” is used on the interior of the wall, applying equal force as the exterior paddle in order to compress the clay evenly. The final exterior contours are shaped with a wooden rib (fig. 24).

Little or no water is used during the forming of the walls. Onggi potters kept a charcoal-fueled burner suspended by a rope in the interior of the vessels to help stiffen the walls (see fig. 19). Most modern-day practitioners use a propane torch; a short blast from the torch on the interior and exterior surface of the newly applied and shaped section facilitates rapid building of the vessel (fig. 25). The finishing of the rim is the last stage of the building. A larger jar or jug can be raised in about half a day. On occasion, David will let a large jar stay on the wheel overnight before he applies a final finish through paddling. Handles are then pulled by hand, shaped, and attached to the final form (fig. 26).

David will continue to make vessels over a several-month period, carefully organizing the finished vessels within his workshop where they must completely dry (fig. 27). David estimates that ninety-five percent of his pots are fired as greenware, intended only to receive the ash glaze of the kiln. Some of his smaller vessels are bisque fired in an electric kiln in order to directly apply simple wood ash or iron glazes. On rare occasions he has used glass cullet to create glass runs for decoration, a tradition developed by nineteenth-century stoneware potters in North Carolina’s Catawba Valley (fig. 28).[23]

Firing the Kiln

Change, risk, and growth are fundamental underpinnings of David’s philosophy of working with clay. While the universal process of wood firing has many shared characteristics, he feels it is important to recognize a kiln’s own unique personality and peculiar firing traits.[24] David tries to use the kiln a little differently each time he fires it, by trying different woods, stacking patterns, and firing schedules.

The flame-shaped kiln David currently uses is a cross-draft style with a chimney stack at one end and the open loading door at the other end (fig. 29). It is approximately thirty feet long and six feet across, and rises to a height of six feet in the center before tapering back down. Five side stoking ports are located on each side. The kiln and adjacent works area are covered by an open-air framed shed.

In contrast to the months spent in solitude in the potting workshop, kiln firing becomes a time of communal activity and close human interaction, necessitated by the twenty-four-hour firing times spanning four or five days. A number of trusted colleagues participate in the firings, usually exchanging their time and labor for coveted kiln space for their own wares (fig. 30).[25] Before loading, the kiln is meticulously swept clean and all of the kiln shelves are inspected for cracks. The inspection and cleaning of kiln shelves and other props is paramount to successful loading of the greenware pots. Clay wadding with a high proportion of sand is prepared and attached to the bases of the pots that go into the kiln to prevent them from fusing to the shelves or floor bricks. Those props are later removed after firing, although occasionally they have to be ground off.

The strategy for loading is one of the most crucial parts of a firing, and David closely supervises that activity. Large-scale pots have to be loaded by two or more people. Fuel of soft pines and mixed hardwoods are sourced from local lumber mills, sorted, and systematically stacked adjacent to the kiln.

After the pots have been loaded, the kiln entrance is bricked up and a heavy metal door is installed for the loading of the fuel. The door can be raised and lowered through a system of cables and pulleys. The firing begins with a small fire started at the mouth of the kiln, which will very gradually warm the interior and the pots.

This primary firebox is continually fed through the front of the kiln, the opening secured by the metal door during the firing (fig. 31). A series of smaller ports on each side of the kiln are also used for stoking during the last three days of a firing, to help ensure even distribution of heat and flames throughout the length of the kiln (fig. 32). Side stoking also helps draw the main flames from the kiln box to the stack end of the kiln, and builds up ember piles in which some of the pots on the floor of the kiln are buried.

Two-person, eight-hour shifts are the standard for these firings, which are hot and exhausting. Mental attentiveness is paramount to constantly monitor the temperature, re-stoking the kiln every 15–20 minutes to achieve a slow, even rise of temperature. David orchestrates the eight shifts over the five-day period, giving instruction, making adjustments, and grabbing sleep when he can. How restful his naps are during firings is questionable, since several months of work is always at stake.

All kilns have different zones that vary in degree of flame, heat, and ash, all of which affect the outcome of the final appearance of the pots. The placement of the pots in the kiln considers those zones, that is, which pots will receive flames directly and others that might be blocked. As a consequence, pots can have a “hot” face and a “cold” face. In addition to stacking the ware in an upright position, some pots are placed on their sides, which affects how the airborne ash is deposited on the pot’s surface and, consequently, its final appearance. As the kiln reaches its highest temperatures, the accumulated ashes in the kiln’s atmosphere begin to melt to form a natural glaze and create dramatic drips and runs down the sides of the pots. The extraordinary jar illustrated in figure 33 was deliberately fired on its side to create a stunning 360-degree galactic landscape of ash, fire, and texture.

The interior temperature of a kiln during firing is monitored in three different ways. The most conspicuous to outside observers is the electronic pyrometer, an instrument which indicates the temperature through a digital readout taken via a metal probe installed in the roof of the kiln (fig. 34). All eyes watch the readout throughout the firing, watching for any sudden upticks or downturns. A slow and steady climb to 2200 °F is usually the desired goal. The pyrometer is not very accurate, however, and is the least important way of gauging temperature.

Since large kilns have temperature differences from top to bottom and horizontal variation, David relies on a series of ceramic pyrometric cones that are placed in various places inside the kiln to provide visual cues about the temperature. He makes up “cone packs,” each with a series of four cones (fig. 35) to better monitor when a specific temperatures is achieved. The temperatures range from Cone 12 (2435 °F) in the front of the kiln to Cone 10 (2381 °F) in the back at the chimney stack. He tries to use these differential temperatures to his advantage, arranging the kiln load knowing that certain pots might fare better in cooler zones of the kiln.

Throughout the firing, the color and quality of the fire’s flame provide visual cues as to the heat of the firing, the customary practice relied on by potters since antiquity (fig. 36). The flames of a fire have several different colors. Depending on the amount of oxygen in the kiln atmosphere and the type of wood used, flame color progresses from a dark red when first started to gradations of orange as the fire reaches its peak temperature. Around 2100 °F, the flames begin to turn a bright yellow. At this temperature, the pots themselves are glowing yellow as well. Eye protection is essential for the firing team when they are monitoring the cones or flame color.

Once the maximum temperature of the firing has been reached, stoking ceases and the kiln vents are sealed. After several days of cooling, the kiln’s door is taken down and the accumulated piles of ash and cinders are swept from the firebox. Excitement is palpable for the first glimpse of the kiln contents, the pots with varying hues of brown, orange, and drippy runs of ash (fig. 37). Vents are opened to help cool the contents but insulated gloves are needed to remove the still warm pots from the shelves. David’s massive jars require several sets of hands and a sling made from an old bedsheet, a technique also used by the Korean onggi potters for handling large pieces (fig. 38). For the smaller pieces, up to a half-dozen sets of hands help carry out the pots carefully laying them out on the adjacent lawn (figs. 39, 40).

Throughout this process, David’s expression rarely changes as he maintains the straight face of a champion poker player (fig. 41). He and his team carefully inspect for any sign of firing flaws as the pieces are removed (figs. 42, 44). The wares from the other potters who have shared kiln space add to the excitement and diversity of the forms and shapes emerging from the kiln (figs. 45, 46).

Sometimes it is obvious that pots have cracked or warped in the firing, and David accepts even the most catastrophic loss as an expected part of the experience. Unlike many potters who are willing to accept small cracks, David sets a high standard for his finished wares. Using a small mallet, he unhesitatingly dispatches those pots he deems unacceptable. The wooded hillside behind his potting workshop is littered with the beautiful culls from David’s firings. Future archaeologists will revel one day at having such a rich repository of David’s firing history to dig through.

After the kiln is fully unloaded the tired, ash-covered crew usually takes a break to celebrate the firing (fig. 47). On one occasion, freshly fired sake cups made by one of the crew members were used to oVer a toast. However, much work remains. The kiln shelves and props have to be scraped clean and carefully restacked. The pots themselves must be cleaned and any residue from the waddings has to be ground off.

Once the pots are ready for sale, the public is invited to the kiln to purchase directly from David (fig. 48). These “kiln openings” are sometimes coordinated with other Seagrove potters’ kiln openings, to be held on highly publicized dates in both the spring and the fall. Occasionally pieces are reserved to be sent off to a gallery or held back for special clients. Once the public visits are over, the cycle renews for David, who begins making new pots for the next firing, which will take place after several months have passed.

The Forms

Typically David creates a broad range of forms, but his signature pots are his distinctive pitchers and jars (fig. 49). He employs two shapes for the pitchers. The first is a more traditional large, ovoid shape with wide shoulders and high-collar necks and rims which echoes British country pottery traditions and nineteenth-century American stoneware forms (fig. 50). The second shape echoes regal English medieval earthenware forms most often seen in British archaeological and museum collections. David experiments with these shapes, throwing both baluster and tapering, conical examples (fig. 51).

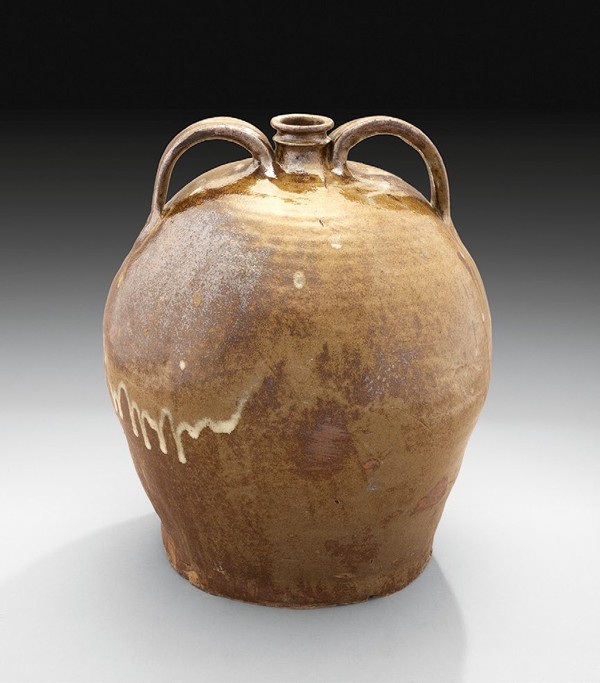

David’s most striking forms are his ovoid jars. Many of the smaller examples mimic the shapes made by traditional potters the world over (fig. 52). His larger examples seem divided equally between American Southern stoneware forms and their Asian counterparts. Variations in rim, handles, and glazing make each example from the firing virtually unique, however (fig. 53). The wide bellies and broad shoulder surfaces provide a marvelous canvas for the accumulation of ash, drip, and flashes created by the flames roaring through the kiln (fig. 54). One of David’s very distinctive jar forms is inspired by earlier traditional Chinese forms that appeared in the Han and Song dynasties—jars with wide bodies tapering to a narrower foot and topped with a tall neck, flaring rim, and three applied handles on the shoulder (see figs. 2, 3). He uses the same ovoid body to create several forms of jugs as well (fig. 55).

David augments his large jars, jugs, and pitchers with a variety of smaller thrown forms that he calls his “tablewares.” They include cylindrical, elongated bottles, pedestal bowls, and gourd-shaped vases (figs. 56 to 57). While at home in any modern setting, the small stemmed bowl illustrated in figure 58 takes its inspiration both from early Korean earthenware examples and porcelain ones made in China during the Yuan and Ming eras. The spouted vessel illustrated in figure 59 is a good example of David’s ever-expanding interests and exploration of vessel forms. Inspired by so-called hand-built earthenware stirrup cups from the ancient Moche culture (100–700 AD) of Peru’s North Coast, this intriguing stoneware version takes on a marvelous contemporary appearance with its runny ash glaze.

Ceramic Inspirations: In His Own Words

I see things from the potter’s perspective—as someone involved in materials and the making process.—David Stuempfle

Ceramics in America editor Robert Hunter asked me to write about some of the historical pottery that has influenced my work. That proved to be a challenging assignment as my tastes are eclectic, global, and span thousands of years of human making. In the interest of clarity, we decided to focus on a small number of potters working along the east coast of America in the nineteenth century. My affinity with their work is based on shared materials and processes, tools and techniques, and my desire to learn from history.

These people were second- and third-generation Americans trained in the United States and working at a time when American stoneware was coming into its own, distinct from its British and European precedents. Beyond the excellence of their work, these makers were agents of change in their local communities and played a pivotal role in the broader stoneware tradition. Some of their work has survived but its meaning has evolved. Pots that were made as household necessities became family heirlooms, then collectors’ items, and finally museum showpieces. What was once a utilitarian container has become a cultural icon, which is asking a lot of pottery. These old pots are like shape shifters traveling through ceramic history.

Thomas Chandler (1810–1854)

Baltimore, Maryland; Edgefield, South Carolina

For me, Thomas Chandler’s work has all the hallmarks of great pottery: beautiful shapes, lively decorations, exquisite glazing, success with fire, and a deep curiosity for materials.[26] Born in Virginia and trained in Baltimore, Maryland, Chandler was a scion of the urban, mid-Atlantic style of salt-glazed stoneware. He arrived in South Carolina in the 1830s as a wounded war veteran. By this time, the basic elements of the Edgefield alkaline-glaze stoneware tradition were in place, and he used his perspective as an outsider to recognize new possibilities for South Carolina stoneware. He was able to blend his own different influences together to form a highly personal style that would continue to develop throughout his career. Other potters absorbed Chandler’s innovations and assimilated them into the Edgefield style. I see this kind of growth often in the Seagrove pottery community where I live; it is a sign of a healthy tradition.

Chandler’s crisply executed forms are both sturdy and graceful, and point to his early training and high standards (fig. 60). His use of slips worked well with the alkaline glaze and his decorations ranged from fluid trailing to figurative brushwork (fig. 61). Glazing must have been a priority for him, as he clearly spent more time formulating, refining, and applying his materials than did his contemporaries. His final product, “patented flintware,” is a tightly vitrified body with a well-fitting celadon glaze (fig. 62).

Chandler is remembered by most for his beautiful pottery, but for me, his greatest quality was his material intelligence and inquisitive mind. This understanding of technology and process was a precursor to what we now call ceramic science.

Frederick Carpenter (1771–1827).

Boston and Charlestown, Massachusetts

A native of Connecticut and trained at the Fenton pottery in New Haven, Frederick Carpenter worked most of his life in Boston and Charleston, Massachusetts. His jugs and jars were some of New England’s first stoneware pots and were made in direct competition to British import pots. The market was ready for American-made products, and a high import tax offset the cost of shipping high-temperature clay from New Jersey and Long Island. The work has a patriotic, almost triumphant nature, and was often stamped with swag and tassels, eagles, shields, and cannons. This work represented a new spirit and marks the ascendency of American manufacturing. Carpenter never owned the shops in which he worked, but was part of a tradition of pottery masters working for investors. At his death in 1827 his identity was lost, only to be rediscovered in the 1950s by the historian Lura Woodside Watkins, and today his work is widely revered and collected. [27]

Frederick Carpenter was a potter of extraordinary talent and skill. From a potter’s perspective, his work is characterized by beautifully proportioned, fully realized shapes with sturdy handles and a deft touch (fig. 63). Often the pots were enhanced by tooled feet, reeded necks, stamped and coggled impressions (fig. 64). His use of iron wash and lack of more elaborate decorations highlighted his masterful shapes and distinctive style. The abundance of kiln scars showed the transformative power of fire and document its mark on the clay.

Carpenter’s clear, articulate pots had a strong impact on me as a young man and were an influence on my early work. Later I was able to handle and photograph many of his pieces at the Smithsonian Museum of American History, and eventually I was in a position to purchase one of his jugs (fig. 65). I know quite a few contemporary potters who keep a Carpenter pot in their collections as a benchmark of excellence and a touchstone to the past.

David Drake (ca. 1800–ca. 1870)

Edgefield, South Carolina

David Drake’s singular expression as a potter and poet has made him the most celebrated American potter of the nineteenth century.[28] Born a slave and died a free man, his life revolved around the pottery community of Edgefield, South Carolina.

Most of Drake’s pots that I have seen and handled have a freshness and immediacy about them that belie their age (fig. 66). He had a relaxed, fluid way of handling clay that retained the softness of the material and left the maker’s mark. The monumental scale of his work exerts a strong physical presence, unusual in his tradition (fig. 67). If Drake never wrote a word on his pots, they would still be pure poetry.

When Drake did decide to write on his pots, he was ready, literacy being something he broke the law to achieve as a young black man. The rhymed couplet was a good fit for the size of his large jars, and the incised words were enriched by the flowing alkaline glaze. His poetry can be read as an act of protest, keen observation, or personal expression. Some of his themes, including war and peace, food and family, race relations and artistic identity, are issues still relevant today. It’s easy to mythologize the story of a one-legged slave potter but wrong to gloss over the harsh realities of the time. That Drake was able to create such beauty under those conditions is a testament to his character and perseverance against all odds. Like many Black artists, he paid the price and others reaped the rewards. In 2007 I was invited to teach a bigware class at the Edgefield Community College. It was an honor to walk in Drake’s footsteps and learn more about his work. I decided to make my first and only “tribute” piece, a fifty-gallon jar with four handles and new rhymes:

This jar was made by Dave for Dave,

The potter is master not slave.Edgefield clay fat and clean

Chinese glaze a sight to be seen.Groundhog kiln burning bright

Like long ago on a starry night.

Daniel Seagle (1805–1867)

Lincoln County, North Carolina

Daniel Seagle was one of North Carolina’s most revered potters and today is still the standard bearer of Catawba Valley pottery.[29] Born in Virginia and brought to North Carolina as a child, Seagle was of Pennsylvania German Lutheran heritage. He was part of the pivotal generation of makers who changed from earthenware to stoneware in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, and worked in a community with dozens of active kilns.

Seagle had the vision and ability to balance utility with beauty. His generous pots are characterized by wide, stable bases that swell into full round shapes with sturdy handles (fig. 68). The clay from the south fork of the Catawba River is a high-temperature, plastic, iron-rich material that was a perfect match for the area’s recently developed alkaline glazes. Seagle also used iron cinders and glass sherds with his glazes, and the flowing surfaces enhanced his monumental forms (fig. 69).

Daniel Seagle was able to pass his craft on to a number of fine potters, among them his son and at least three apprentices. Isaac Lefever in particular made pots that equaled or surpassed the quality of his teacher before his death in the Civil War at age thirty-three. Lefever’s work has attributes often seen in young potters: expectant, energetically athletic, and technically precise. His early death gives his career the aura of unrealized potential and the possibility of what might have been. Of all the Catawba potters, Isaac Lefever’s jugs and jars have had the most influence on my shapes (fig. 70).

By the end of the twentieth century, the Catawba Valley tradition had come down to just one person, the late Burlon Craig. Craig was a powerful teacher and mentor, and during the 1980s and 1990s he was able to pass this tradition on to a new generation. Through Seagle’s influence on Craig, Seagle’s apprentices and neighbors started a tradition in the Catawba Valley that is still producing, and, along with Seagrove, is one of the oldest non-Native pottery communities in America.

Chester Webster (1799–1882)

Hartford, Connecticut, and Randolph County, North Carolina

Brothers Edward, Timothy, and Chester Webster were members of a prominent traditional pottery-making family in Hartford, Connecticut. Seeking to expand their business opportunities in the South, the brothers eventually relocated to Fayetteville, North Carolina, to open a new pottery.[30] With the backing of investors, they started to make some of the first salt-glazed stoneware in the Carolinas (fig. 71). Their early Fayetteville work was a direct continuation of the Hartford style: fully ovoid shapes, jump handles with backfilled terminals, and the incised decoration that was a Connecticut Valley specialty. Their wares were coated with an iron wash and fired in Northern-style upright kilns.

By the end of the 1820s, the venture in Fayetteville had failed for a variety of reasons, and Chester had moved to what is now the Coleridge community of Randolph County, North Carolina, where he spent the rest of his career working with the Craven pottery family, who had excellent clay and an established market. Edward continued to work in Fayetteville for the next decade, and eventually he and Timothy worked some in Randolph County.

Chester Webster was flexible and able to adapt his work to his new circumstances and made pottery that was both compelling and highly personal. Much like Thomas Chandler in South Carolina, Webster brought a Northern influence to Southern stoneware and created a fusion ware that incorporated the best of both styles that is still apparent today. Both men’s work exhibited a self-awareness, as though they knew they were making work that was outstanding and would be influential in the future. Clearly, they were trying to communicate more of a sense of artistic identity than their contemporaries.

Webster’s New England ovoid shapes gradually became classic Southern beehives; jump handles evolved toward the Craven fold style; and cross-draft groundhog kilns marked his work with dramatic firing effects. He continued to decorate some of his pots with animated incisions: birds tweeting tunes with captured insects; fish flashed their teeth as they went for the hook; and rhythmic stamped patterns punctuated the figurative drawings and accentuated the strong proportions of the pots (figs. 72, 73).

I have always felt a kinship with Chester Webster; I work within ten miles of where he worked, and use some of the same materials, tools, and techniques. Those include local silica rich clays, stand-up treadle wheels, and wood-fired cross-draft kilns. Like him, I am a Northern potter navigating a strong Southern tradition. Working in a traditional pottery community has given my work a sense of place and history while providing broad perimeters and the encouragement to innovate. I think of Webster every time I cross the Deep River. Coleridge is an unincorporated community along the Deep River in Randolph County, North Carolina. This is where he worked—the site of the old Craven family homestead and the original Seagrove area pottery.

David Stuempfle’s Legacy

David’s ceramic career has touched the lives of many. He has gained the notice of ceramic art critics, museum curators, and collectors, but most importantly he has cultivated a legion of colleagues from around the world. While all are spellbound by the great strength and beauty of his pots, it is truly David’s personality, spirit, and generosity that is called out time and time again among his admirers. It is appropriate to conclude this article with some of those voices.

Charlotte Vestal Brown has written extensively on North Carolina potters and pottery, and has curated numerous shows as the former director of the Gregg Museum of Art & Design at North Carolina State University. She was an early chronicler of David’s artistic vision in her encyclopedic The Remarkable Potters of Seagrove (2006).

He desires to create work that expresses universal values and gathers traditions from many places. . . . He simply permits wood ash and the fire itself to enhance the work with a variety of textures, color graduations, and shimmering ash runs that delight the eye. His pieces are as individual as people, reinforcing the obvious: that every handmade pot is different from every other, and therein lie their powerful beauty and their purpose.[31]

Mark Hewitt is a fellow potter living and working in the nearby town of Pittsboro, North Carolina. Born and trained in England, Mark was taught by the famed woodfire potter Michael Cardew, who himself was trained by Bernard Leach. Like David, Mark has traveled and worked abroad. He is a scholar and writer whose publications and ceramic art have earned him international acclaim. Of particular note is his 2005 publication The Potter’s Eye: Art and Tradition in North Carolina Pottery, coauthored with Nancy Sweezy. More recently he organized an exhibit and book, Great Pots from Traditions of North & South Carolina, for the North Carolina Pottery Center.

Dave Stuempfle’s pots assimilate several strands of ceramic excellence and have as a foundation the stoneware traditions of New England, North Carolina, Korea, and Japan. His early training at Seagrove’s Jugtown honed his eye, stints as a production potter at Rockdale Pottery in Wisconsin sharpened his exemplary throwing skills, and time in Korea learning how to make large kimchi jars helped him develop the scale for which he is greatly admired. Using good local clays, developing excellent making skills, and building a large wood-burning kiln which is fired for several days is not easy. Stuempfle has never shortchanged the process and the results are a testament to his tenacity. Clean-lined and robust, his handsome pots have luscious surfaces of great complexity, and they have an integrity which radiates patience, kindness, and generosity.

Michelle Erickson is an independent ceramic artist and scholar working in Tidewater, Virginia. She is internationally recognized for her mastery of colonial-era ceramic techniques and her twenty-first-century social, political, and environmental narratives.[32] In 2018, her exhibit “Michelle Erickson: distilled” at the North Carolina Pottery Center featured her contemporary work that revolves around the topics of alcohol consumption and historical ceramic drinking vessels.[33] She has collaborated with David in many of his firings, adding wood-fired technology to her repertoire of ceramic tools. Some of her recent works, fired in David’s kiln, appear in her exhibition “Wild Porcelain” at the Legion of Honor’s Bowles Porcelain Gallery in San Francisco and were published in British Art Studies.[34]

David Stuempfle and Nancy Gottovi are the quietly remarkable power couple of Seagrove, North Carolina, neither seeking the spotlight but both investing their considerable creative forces in the Seagrove pottery diaspora. My first introduction to David was through an example of his work on display at the North Carolina Pottery Conference in 2013, where I was a guest demonstrating artist. A pedestal bowl caught my attention, the self-possession of the piece visible from across the room and when held on closer inspection—a work of art in clay. When David introduced himself to me at the conference I was unaware he was the artist whose work I had just admired and he was unaware of my interest. He had approached me after seeing my demonstration to encourage me to come to Seagrove to practice and explore the region’s unique ceramic history, and extended his and Nancy’s hospitality to help facilitate the idea. David and Nancy’s austere powers of persuasion initiated my 2016 artist residency at STARworks and began a now six-year friendship and extraordinary experience of learning to crew on and fire with David in his biannual five-day wood firings. Plus it has to be said he makes a mean double expresso.

Susan and Bill Mariner are eminent collectors of historical pottery and have established the William C. and Susan S. Mariner Southern Ceramics Gallery at the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts in Winston-Salem.[35] The gallery is home to the most comprehensive collection of antebellum pottery made in the Carolinas, Georgia, Kentucky, Maryland, Tennessee, and Virginia. They have long admired the work of David and have collected a number of pieces for their personal collection. Both were excited to participate in a recent firing, assisting with the stoking and other tasks.

The first time we saw David’s pottery we were intrigued. The two jars we encountered shared a very traditional form yet the glaze on each one was something we had never seen before. We were so captivated by the jars that we decided to visit him the next time we were in Seagrove. We love his work and have now collected several pieces of his art, from very large jars and jugs to small bowls and pitchers. David also let us participate in one of his burnings, which was so very generous (fig. 74). We spent most of one day helping to load wood into his kiln, an experience we will never forget and are very glad to have been given the opportunity. Another interesting thing about visiting David and Nancy is that they have rescue dogs (Great Pyrenees and basset hounds) that live out their days in this wonderful spot in North Carolina.

Stephen Compton is a prominent researcher and historian of North Carolina pottery. He has authored numerous articles and books, including Seagrove Potteries through Time and It’s Just Dirt! The Historical Art Potteries of North Carolina’s Seagrove Region. His interests include the full range of North Carolina pottery making, from those of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to the contemporary potters who still carry on the tradition. He recently organized at the North Carolina Pottery Center an exhibit of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century vessels titled “In the Pale Moonlight: Jugs and Alcohol in North Carolina.”[36]

Had they considered it an undesirable trait, North Carolina’s highly skilled nineteenth-century stoneware makers could have prevented firing scars, burns, streaking runs, and patches of glass from marring otherwise uniformly glazed surfaces. Enough of the Seagrove region’s old pots bear such signs of fire’s fury to suggest that their creation was anticipated, tolerated, and may have been, at times, intentional. Collectors eagerly vie for them. David Stuempfle has undoubtedly seen many of these pots “decorated” by a kiln’s fiery dragon’s breath, and he must draw some inspiration from them. With every kiln-load of ware, he expects fire and whorls of wood ashes to do the decorating. But no amount of planning or manipulation can predict what art the fire will lay down on the clay, making each piece unique. His knowledge and experience, in league with the fire, make it likely that “art” will occur, and that connects his work to that of local folk potters a century ago. Theirs was utilitarian, but was it ever art? David’s is indisputably art. Very fine art.

Henry Glassie is a renowned folklorist who is College Professor Emeritus at Indiana University Bloomington. Henry has conducted fieldwork on five continents and written widely in the fields of material culture and vernacular architecture. His work with potters from Bangladesh, Japan, Sweden, Turkey, and various parts of the United States provided the basis for his highly acclaimed book The Potter’s Art.[37] He is particularly invested in the history of the Southern wood-fire tradition and has recently completed a biography about a like-minded ceramic artist, Daniel Johnston: A Portrait of the Artist as a Potter in North Carolina.[38]

From his home in Pennsylvania, David traveled to learn through the United States and eastern Asia, settling on a farmstead in the vibrant potters’ district of Seagrove in North Carolina, where magnificent works of art spin from his hands. A skilled musician and a master of the potter’s art, David works alone to the highest standard, but he is a treasured member of his community, always generously praising the work of his colleagues. Local clay in David’s hands becomes at once bold and controlled, vital, wild, and spiritually centered. His pots contain the intricacy of an Irish reel and the swelling solemnity of a shape-note hymn. Working at a monumental scale, David strives for impeccable precision, then surrenders his masterworks to the kiln where, fired hard and long, they gather flying ash onto surfaces of exhilarating, energetic surprise.

Epilogue

This article has presented a summary overview of the David Stuemfple’s wood-fired ceramic practice in Seagrove, North Carolina. Of particular emphasis is the international scope of his work, both with his research of world traditions that he draws on for inspiration, and his face-to-face networking with other working potters from around the globe.

For the foreseeable future, David plans to continue his semiannual firings in Seagrove and to pursue more focused marketing with galleries and museums (figs. 75, 77). He maintains an active online presence with a website and social media postings.[39] Travels plans include visits to Portugal to explore the rich ceramic heritage of that country.

Future educational initiatives where David will be participating include the planned Woodfire NC: Envision, an International Wood Fire Conference.[40] The 2022 conference will kick off in May with two pre-conference events in separate locations in the state: preHEAT: Mountain and preHEAT: Seagrove, where local and visiting artists will load and then fire dozens of kilns located around the Asheville area and Seagrove. The main conference will begin on May 27 at STARworks with topics ranging from kiln design to group firings and community engagement.

https://www.stuempflepottery.com/process.

Jack Troy, Wood-Fired Stoneware and Porcelain (Radnor, Pa.: Chilton Books, 1995).

https://kogeijapan.com/locale/en_US/echizenyaki/ states that “Echizen ware (called Echizen yaki in Japanese) is a type of pottery produced in the town of Echizen, Fukui prefecture.” Echizen ware is notable for its natural glaze, which comes from wood ash. Louise Allison Cort, Shigaraki, Potters’ Valley (1979; Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1981); Donald Alan Wood, Echizen: Eight Hundred Years of Japanese Stoneware (Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Museum of Art, 1994).

The 2017 International Wood Fire Conference was held June 8–10, preceded by a series of three regional pre-conference wood firing workshops across the state near Asheville, Seagrove, and Bailey, North Carolina from May 26 to June 7. The conference was sponsored by STARworks, the North Carolina Pottery Center, and the woodfire potters of North Carolina. More than sixty artists and leaders in the field of ceramics presented lectures, demonstrations, and panel discussions examining the foundational role that clay has in the practice, and a variety of technical and aesthetic concerns.

In 2016 the Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina, invited David Stuempfle to create a yearlong exhibit devoted to North Carolina pottery in the context of other pottery traditions across time and space. He selected North Carolina objects paired with ceramics from ancient America, Asia, and Africa. Stuempfle stated: “There’s a universal quality to great pots and I wanted to show the similarity. Instead of segregating these pots based on cultural geographies, we chose to bring these pots together to show that universality.” https://mintmuseum.org/david-stuempfle-selects-north-carolina-pottery-in-a-global-context/

David Stuempfle, “Risk Tradition and Growth,” The Log Book, no. 69 (February 2017), pp. 18–21; Charlotte V. Brown, The Remarkable Potters of Seagrove: The Folk Pottery of a Legendary North Carolina Community (New York: Lark Books, 2006); Mark Hewitt and Nancy Sweezy, The Potter’s Eye: Art and Tradition in North Carolina Pottery (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the North Carolina Museum of Art. 2005), pp. 248–62.

John Bivins Jr., The Moravian Potters in North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for Old Salem, Inc., 1972); Luke Beckerdite and Johanna Brown, “Eighteenth-Century Earthenware from North Carolina: The Moravian Tradition Reconsidered,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2009), pp. 2–67.

Hal Pugh and Eleanor Minnock-Pugh, themselves working potters, further the story of North Carolina earthenware in “The Quaker Ceramic Tradition in Piedmont North Carolina,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2010), pp. 66–105.

Jay Althouse, “An Introduction to Seagrove Pottery,” Folk Art Society of America 24, no. 2 (2013), https://folkart.org/mag/introduction-seagrove-pottery.

Stephen C. Compton, Seagrove Potteries through Time, America through Time ([Stroud, Eng.]: Fonthill Media, 2013).

Stephen C. Compton, It’s Just Dirt! The Historic Art Potteries of North Carolina’s Seagrove Region ([Stroud, Eng.]: Fonthill Media, 2014).

Jack Petrash, Understanding Waldorf Education: Teaching from the Inside Out (Beltsville, Md.: Gryphon House, 2002).

Quoting Jon McAlice, https://www.freunde-waldorf.de/en/the-friends/publications/catalogue-waldorf-education/learning-through-rhythm/

Jane Powell, “ ‘S’ Stands for ‘Super’, ” Nashville Magazine 4, no. 8 (November 1976).

Hewitt and Sweezy, Potter’s Eye, p. 249.

Compton, It’s Just Dirt!, pp. 95–102.

Nancy Sweezy, Raised in Clay: The Southern Pottery Tradition (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1984).

See https://www.ashevilleart.org/work-of-the-week/jar-david-stuempfle/ for a 1994 example of a large jar now in the Asheville Art Museum (Gift of Robert Williams in memory of -Warren Womble, 2020.17.02).

Stuempfle, “Risk Tradition and Growth,” pp. 18–21.

https://www.starworksnc.org/starworks-clay.

Nic Collins, Throwing Large (London: A&C Black, 2011), pp. 105–8.

Robert Sayers and Ralph Rinzler, The Korean Onggi Potter, Smithsonian Folklife -Studies 5 (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987).

Jason Harpe and Brian Dedmond, Valley Ablaze: Pottery Tradition in the Catawba Valley (Conover, N.C.: Goosepen Studio & Press, 2012).

http://www.woodfirenc.com/david-stuempfle-1.

There have been over one hundred people who have helped fire David’s kiln over the years. It takes about twelve people to do a five day burn. In addition to a trusted local crew, David has welcomed guests from further afield and overseas. Increasingly, residents from STARworks and the North Carolina Pottery Center have helped.

Phillip Wingard, “From Baltimore to the South Carolina Backcountry: Thomas Chandler’s Influence on 19th-Century Stoneware,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2013), pp. 38–76; “Swag & Tassel: The Innovative Stoneware of Thomas Chandler,” McKissick Museum, Columbia, South Carolina, Exhibit Catalog, August 2018.

Lura Woodside Watkins, “New Light on Boston Stoneware and Frederick Carpenter,” The Art of the Potter: Redware and Stoneware, edited by Diana Stradling and J. Garrison Stradling (New York: Main Street/Universe Books, 1977), p. 82; Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (1950; [Hamden, Conn.]: Archon Books, 1968), p. 81; Lorraine German, “Eighteenth-Century Boston Stoneware: Appealing to a Local Market,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Havertown, Pa.: Casemate Publishers for the Chipstone Foundation, 2019), pp. 85–106; Lorraine German, “The Little Pottery of Charlestown, Massachusetts,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Havertown, Pa.: Casemate Publishers for the Chipstone Foundation, 2021), pp. 88–101.

Cinda K. Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar: Traditional Stoneware of South Carolina (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993); Arthur F. Goldberg and James Witkowski, “Beneath His Magic Touch: The Dated Vessels of the African-American Slave Potter Dave,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2006), pp. 58–92; Michael A. Chaney, Where Is All My Relation? The Poetics of Dave the Potter (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018); Todd Leonard, Carolina Clay: The Life and Legend of the Slave Potter Dave (New York: W.W. Norton, 2009).

Charles G. Zug III, Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986); John Nash, “Daniel Seagle and James F. Seagle,” in Potters of the Catawba Valley, edited by Daisy Wade Bridges (Charlotte, N.C.: Mint Museum, 1980), p. 16.

Quincy J. Scarborough, North Carolina Decorated Stoneware: The Webster School of Folk Potters (Fayetteville, N.C.: Scarborough Press, 1986); Quincy Scarborough and Samuel Scarborough, The Webster School of Folk Potters (1986; Fayetteville, N.C.: Privately published, 2009); Quincy Scarborough, “The Webster School of Folk Potters,” Journal of Early Southern of Decorative Arts (1984): 36–37.

Brown, Remarkable Potters of Seagrove, p. 103.

http://www.michelleericksonceramics.com.

Robert Hunter, “Michelle Erickson DISTILLED,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2018), pp. 46–67.

“Wild Porcelain,” British Art Studies, no. 21, https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-21/covercollaboration.

https://mesda.org/exhibit_category/mariner/.

Stephen C. Compton, “In the Pale Moonlight: Jugs and Alcohol in North Carolina,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2018), pp. 68–93.

Henry Glassie, The Potter’s Art (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1999).

Henry Glassie, Daniel Johnston: A Portrait of the Artist as a Potter in North Carolina (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2020).

https://www.stuempflepottery.com, https://www.facebook.com/stuempflepottery, https://www.instagram.com/davidstuempflepottery/?hl=en.

www.woodfirenc.com.