David Stuempfle at his kiln during a firing in the spring of 2016. (Unless otherwise noted, all photos by Robert Hunter.)

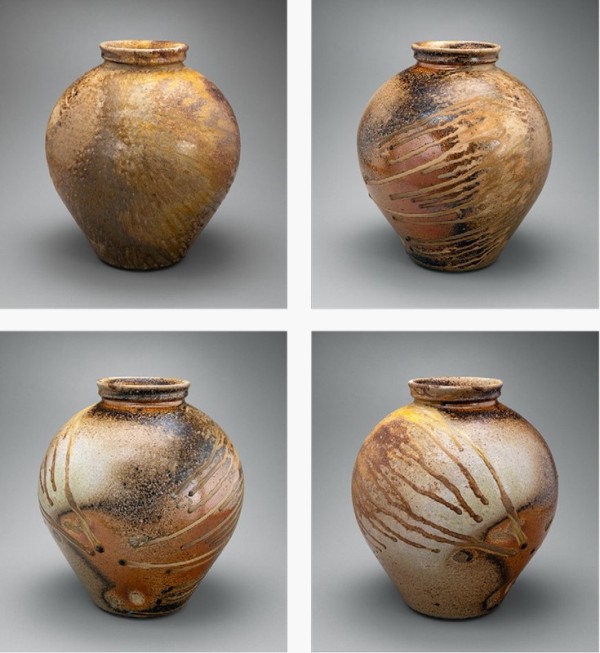

“Chinese” jar, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2016. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 34". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Detail of the jar illustrated in fig. 2.

Storage jar, Shigaraki Valley region, Japan, Muromachi period

(1392–1573). Stoneware with natural ash glaze. H. 18 3/8”. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Harry G. C. Packard Collection of Asian Art, Gift of Harry G. C. Packard, and Purchase, Fletcher, Rogers, Harris Brisbane Dick, and Louis V. Bell Funds, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, and The Annenberg Fund Inc. Gift, 1975.)

Onggi jar, Oh Hyang Jong, David Stuempfle Pottery, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2001. Wood-fired stoneware. H. 60". (David Stuempfle collection) This massive jar was made by a visiting South Korean artist and fired in David’s kiln. Oh Hyang Jong came to Seagrove three or four times in the early 2000s and often brought other Korean artists with him.

Map showing the location of the town of Seagrove within Randolph County in North Carolina’s Piedmont (Map, Wynne Patterson.)

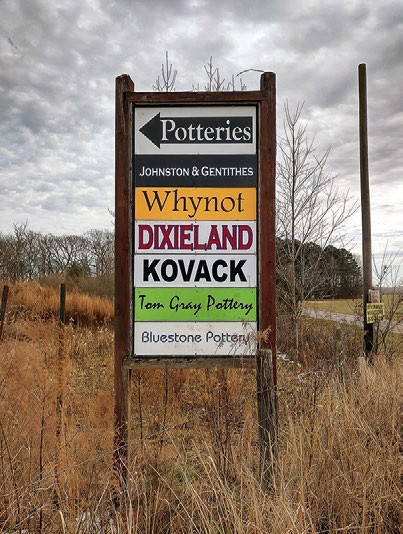

Highways signs in Seagrove,

at exit 45 off i-73/i-74. (Photo, Lindsey Lambert.) North Carolina Highway NC 705 is designated as the Pottery Highway or Pottery Road, and is a registered North Carolina Scenic Byway.

Signs seen along the Pottery Highway at nearly every crossroads direct visitors to the many potteries that dot the landscape. (Photo, Lindsey Lambert.)

David Stuempfle’s kiln shed and potting workshop during a firing in 2016.

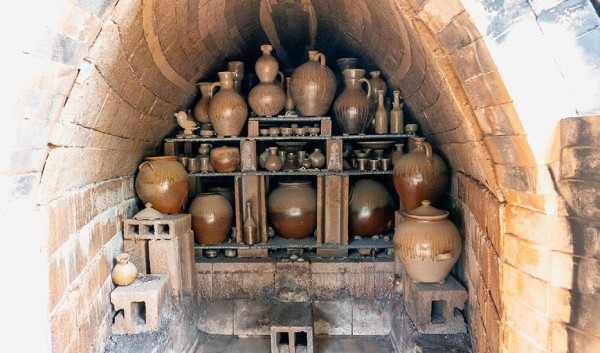

Groundhog kiln being fired at the North Carolina Pottery Center, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2016. This working kiln is used for demonstrating the wood-firing process. The firing takes approximately fifteen hours and requires two cords of wood.

David Stuempfle at a firing of the groundhog kiln at the North Carolina Pottery Center, Seagrove, 2016. The single doorway facilitates both loading the ware and stoking the kiln.

Michelle Erickson unloads a fired pot through the narrow door of the groundhog kiln at the North Carolina Pottery Center, 2016.

Nancy Gottovi with bloodhound friend, 2016.

Nancy Gottovi opening a side port to the kiln during a firing in May 2016.

Pitcher, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 1995. Salt-glazed stoneware with applied ash glaze. H. 14". (Private collection.) The tapering cylindrical form of this tall pitcher is reminiscent of English medieval pottery. The ash encrustation is the result of being buried in the kiln’s ember pile.

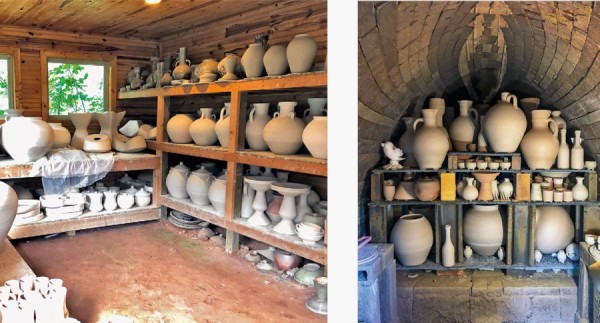

Greenware drying on the shelves in David Stuempfle's workshop (left) and arranged on the shelves of the kiln during loading (right). (Photos, Michelle Erickson.)

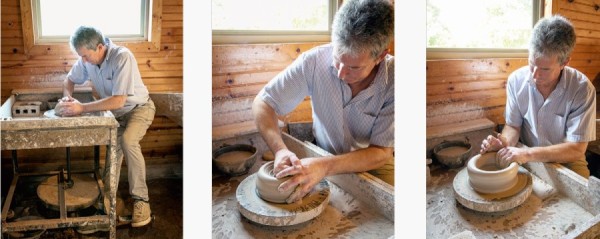

Throwing on a traditional treadle wheel. For his small work, what he calls “tableware,” David uses this foot-powered wheel to raise his vessels.

A flower pot being raised on the treadle wheel.

Drawing, Kim Jun-Geun (Kisan) (Korean, 1850/1950), Korea, ca. 1880–1890. (© British Library Board, acc. no. 14344.) This nineteenth-century drawing shows an onggi potter raising a jar on a treadle wheel using a wooden paddle and an anvil to stretch and shape the pot.

Large ropes or coils of clay are formed and rolled by hand.

The coil is attached to the rim of the pot and thumbed into the wall of the pot.

The coil is further worked by hand into the wall of the pot.

The pot is slowly rotated as the attached coil is compressed using a series of carved paddles. A wooden “anvil” is used to compress the interior wall during this process (see fig. 19).

A wooden rib helps shape the final contours of the body.

Using a propane torch, the newly applied and shaped section must dry for several minutes to stiffen the wall before the next coil can be applied.

After the final form of the vessel is achieved, the rim is shaped and handles are applied.

A group of greenware pots dry in the shop before being loaded into the kiln for firing.

A large Han-style jar with glass runs being removed from David Stuempfle’s kiln by Owen Laurion as Rose Hardesty awaits her turn to enter the kiln.

The large kiln during firing in 2016.

Seagrove potter Chad Brown during the loading of greenware into the kiln. Note the use of shelves to create layers of firing space. (Photo, Michelle Erickson.)

Stoking the main firebox. Access holes beneath the door allow venting of the kiln to remove excess cinders and ash during firing.

Seagrove potter Takuro Shibata stokes one of the side ports.

Storage jar, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2020. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 15". (Private collection.) This ovoid jar was placed on its side on the kiln floor, which allowed ash to accumulate on the side facing up, creating dramatic runs from the melted wood ash.

An electronic digital pyrometer is used to monitor the temperature inside the kiln. The temperature is gradually increased over the four- or five-day firing period until the kiln reaches its peak temperature, about 2435 °F.

A series of pyrometric “cones” are placed in the firing chamber to gauge when sufficient temperature has been achieved. The cones will bend to indicate temperatures between Cone 12 (2435 °F) in the front of the kiln and Cone 10 (2381 °F) in the back.

The color and quality of the flames as observed through the firebox are additional indicators of temperature and the amount of carbon contained in the atmosphere. Protective eyewear is essential.

The first view of the fired kiln immediately after opening.

Seagrove ceramic artist Fred Johnston works with David to remove a large storage jar from the kiln using a bedsheet sling. (Photo, Michelle Erickson.)

First view of a large jug/bottle as it emerges from the kiln. Often pots are extremely warm at this stage, necessitating insulated gloves to carry them.

The still-warm pots are systematically laid out on the lawn adjacent to the kiln.

David emerges from the kiln carrying a large jar.

David closely inspects the base of a large jar.

Michelle Erickson and David Stuempfle assess a group of wares.

Stillman Browning-Howe, a regular member of David’s firing team, inspects a jar after it has emerged from the kiln. The circular marks on the bottom are from the wadding spacers.

Anne Pärtna (left) examines a bowl removed from the kiln. Anne is a native Estonian and has her own ceramic practice in Seagrove but often fires some of her larger works (right) in David’s kiln.

Michelle Erickson showing two of her stoneware jugs fired in David’s kiln in 2019.

A 2020 firing and kiln unloading crew during times of Covid 19. Left to right: Stillman Browning-Howe, Hamish Jackson, Miki Palchick, John Freeman, David Stuempfle, and Michelle Erickson.

A selection of vessel forms just unloaded from the 2020 firing of David Stuempfle’s kiln.

David examines one of his traditional pitcher forms immediately after it was unloaded from a kiln firing.

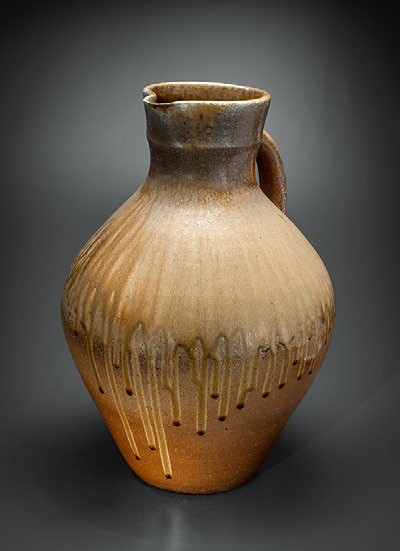

Ovoid pitcher, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2016. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 19". (Private collection.)

Medieval pitcher, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2018. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 18". (William C. and Susan S. Mariner Collection.)

Storage jars, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2015. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/2“. (Private collection.) Two ovoid storage jars as they appear immediately after firing, with well‑developed wood-ash glaze and carbon deposits.

Storage jars, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2019. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 24". (Private collection.)

Jar, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2018. Slip and ash-glazed stoneware. H. 25". (Asheville Art Museum; Gift of Robert Williams in memory of Warren Womble, 2020.17.02. © David Stuempfle.)

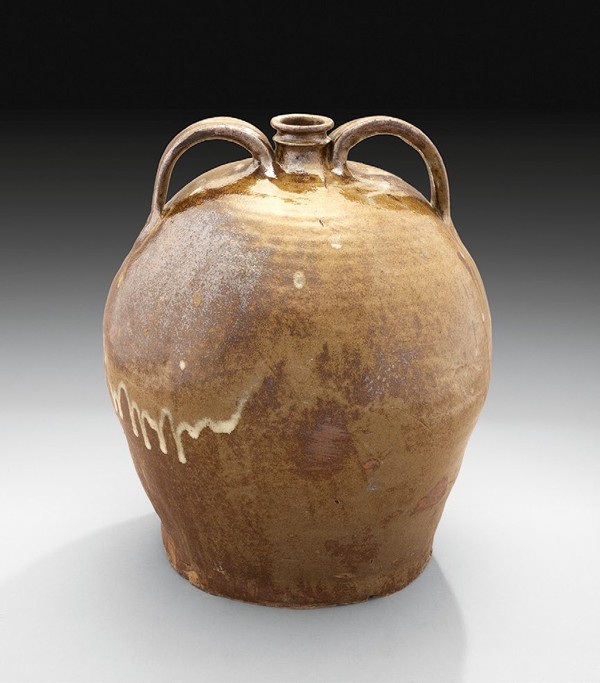

Two-handle jug, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2018. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 24". (Private collection; photo, Jason Dowdle.)

Gourd-shaped vase, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2016. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 20". (Private collection; photo, Jason Dowdle.)

Pedestal bowl, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2018. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 12". (Private collection; photo, Jason Dowdle.)

Stemmed bowl, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2016. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 9" (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Stirrup vessel, David Stuempfle, Seagrove, North Carolina, 2017. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/2. -(Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Storage jar, Thomas Chandler, Edgefield County, South Carolina, 1840–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16 3/8“. (William C. and Susan S. Mariner Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) This large jar is embellished with Chandler’s distinctive two-color

slip-decorated swag design.

Syrup jug, Thomas Chandler, Edgefield County, South Carolina,

1840–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16 3/8“. Mark: “CHANDLER / MAKER” (Private collection.) This classically shaped jug is embellished with a white slip-decorated design.

Detail of storage jar, Thomas Chandler, Edgefield County, South Carolina, 1840–1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16 1/2“. (The Joseph P. Gromacki Collection.)

Detail of storage jar, Frederick Carpenter, Little Brothers Pottery, Charlestown, Massachusetts, ca. 1800–1810. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 14 1/2“. (The Joseph P. Gromacki Collection.)

Storage jug, Frederick Carpenter, Charlestown, Massachusetts, ca. 1812–1827. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16". Impressed with three hearts, indicating three gallons. (The Chapman Collection.) This jug is illustrated in Mark Hewitt and Nancy Sweezy, The Potter’s Eye: Art and Tradition in North Carolina Pottery (Chapel Hill: Published for the North Carolina Museum of Art by the University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

David Stuempfle examines a three-gallon jug from his collection, made by Frederick Carpenter in Charlestown, Massachusetts, ca. 1812–1827.

Jug, David Drake, Lewis J. Miles Pottery, Edgefield County, South Carolina, ca. 1850s. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 17". (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation; 1939-137.)

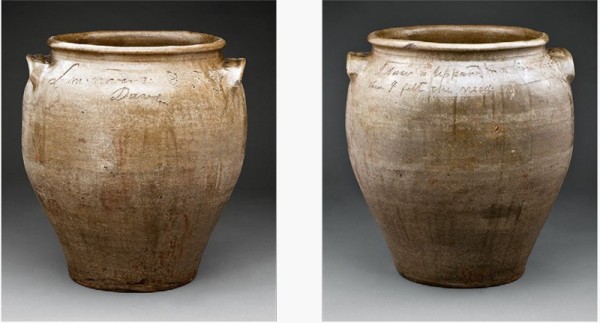

Storage jar, David Drake (1800–ca. 1873), Edgefield County, South Carolina, dated 1858. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 24 1/4.” (Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, MESDA Purchase Fund, 4317.) One side of this jar is inscribed “L.m. nover 3, 1858 / Dave.” The other is marked “I saw a leopard & a lions face/ then I felt the need—of grace,” an adaptation from the Book of Revelation.

Storage jar, Daniel Seagle, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 19 3/4 Stamped twice: DS (Private collection.) This storage jar holds 16 gallons.

Storage jug, Daniel Seagle, Lincoln County, North Carolina, 1830–1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16". (Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts; Loan courtesy of Beverly Owens Jaynes.)

Storage jar, Isaac Lefever, Lincoln County, North Carolina, 1850–1860. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16". (William C. and Susan S. Mariner Foundation.)

Jug, attributed to Edward Webster, Fayetteville, North Carolina, 1820–1821. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 16 1/2“. (William C. and Susan S. Mariner Foundation; photo, Crocker Farm, Inc.)

Storage jar, Chester Webster, Randolph County, North Carolina, dated 1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/8“. (Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.)

Detail of the jar illustrated in fig. 72.

Michelle Erickson stokes the kiln with slabs while firing crew Bill and Susan Mariner wait their turn. Potter Matt Levy looks on.

David emerges from the kiln with one of his signature gourd-shaped vases.

A group of gourd-shaped vases in the workshop awaiting sale.

David and Josephine with an assortment of his ash-glazed stonewares after a kiln firing in 2019.