Detail of the lid of the snuff box illustrated in fig. 2. (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Snuff box, attributed to the A-marked group, east London, England, ca. 1744–1745. Hard-paste porcelain with enamels. D. 2 3/8". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, courtesy Errol Manners.)

View of the snuff box illustrated in fig. 2 with the lid open showing its gilded copper collar. (Chipstone Foundation; photo, courtesy Errol Manners.)

Side view of the snuff box illustrated in fig. 2 with sailing vessel and castle. (Chipstone Foundation; photo, courtesy Errol Manners.)

Side view of the snuff box illustrated in fig. 2 with castle and bridge. (Chipstone Foundation; photo, courtesy Errol Manners.)

View of the bottom of the snuff box illustrated in fig. 2. (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

View of the interior bottom of the snuff box illustrated in fig. 2 revealing a faintly incised “A” mark. (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Snuff box, attributed to the A-marked group, east London, England, ca. 1744–1745. Hard-paste porcelain with enamels. Diam. 2 3/8". (National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, De Winton Collection of Continental Porcelain, acc. no. D.W. 552). Enameled with an “A” or “V” incised. The body of the box is decorated with various flowers and leaves within panels of intertwined scrolls. A scene set within a scrolled cartouche comprising a castellated building and barrels is depicted on the lid.

Snuff box, attributed to the A-marked group, east London, England, ca. 1744–1745. Hard-paste porcelain with enamels. Diam. 2 3/8". (Private collection.) The body and lid are enameled with a butterfly, fruit, flowers, and leaves.

Hexagonal teapot, attributed to the A-marked group, east London, England, ca. 1744–1745. Hard-paste porcelain with enamels. H. 4 1/4." (V&A Museum collections, C.207-1937.) Underglaze blue “A” under base and inside lid. The iron-red cartouche and the mascarons link this teapot to the Cardiff snuff box illustrated in fig. 8.

Teapot, attributed to the A-marked group, east London, England, ca. 1744–1745. Hard-paste porcelain with enamels. H. 3 7/16". Underglaze “A” on base. (V&A Museum collections, C.1-1991.) This teapot, formerly in the Geoffrey Godden Collection, uses scenes from a series of youthful diversions designed by Gravelot and published by Cole on October 24, 1740. The two scenes depicted are titled Bow and Arrows and Playing with Marbles. The pot is also linked to the Cardiff snuff box by way of an iron-red cartouche and mascarons.

Cane handle, attributed to the A-marked group, east London, England, ca. 1744–1745. Hard-paste porcelain with enamels. H. 1 3/4". Unmarked. (V&A Museum collections, C.148-1993.) Three flanking scenes supposedly in the Meissen manner with a prominent shell in iron red. Elizabeth Adams, “‘Birmingham’ Porcelain,” Antique Dealer and Collectors Guide (November 1992): 22–27.

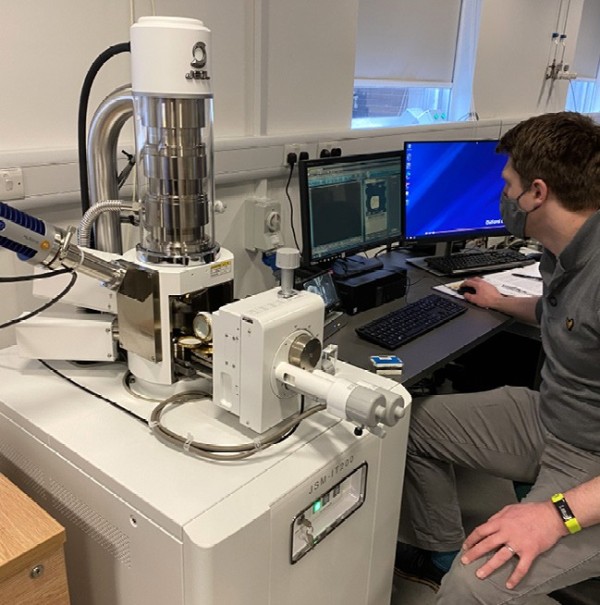

The JEOL JSM-IT200 SEM coupled with an Oxford Xplore 15mm2 EDX detector, Brunel University, London, operated by Dr. Ashley Howkins. The snuff box can be seen on its side with its lid open prior to being inserted into the SEM chamber (red arrow)

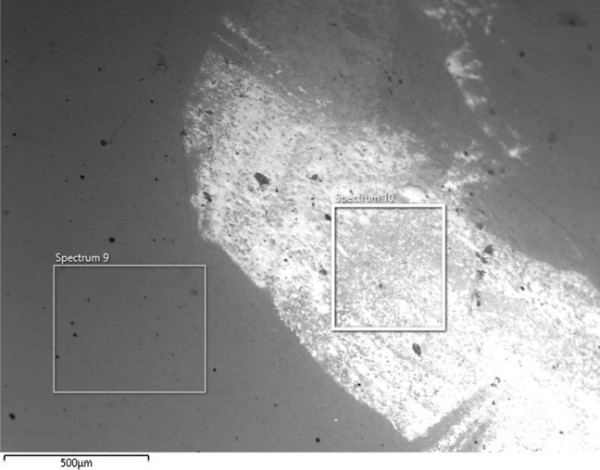

Compositional back-scattered electron SEM micrograph acquired from the area of the red flag enamel design on the main body of the porcelain snuff box illustrated in fig. 2. The high-contrast region (brighter) is from the pigmentation of the red enamel, whereas the gray regions are from the background white glaze of the porcelain. Boxes demonstrate small area EDX analyses carried out within areas of interest.

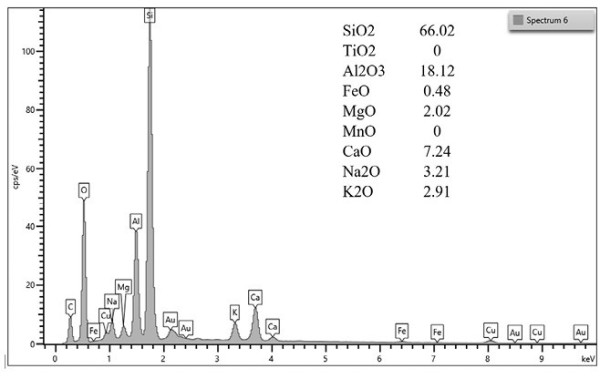

Spectrum 6 of the porcelain body on the rim to the snuff box adjacent to gold-copper collar, free of glaze. The calculated analysis shown in the right in the figure has had both gold (3.36 wt% Au2O3) and copper (1.95 wt% CuO) removed.

Two coffee cups, attributed to the A-marked group, east London, England, ca. 1744–1745. Hard-paste porcelain with enamels. H. of top cup 2 3/8", H. of bottom cup 2 1/4". (Private collections; courtesy of John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.) Both are slip-cast with decagonal foot rims. The cup on the top is decorated with European-style flower sprays; the cup on the bottom has six alternating vertical panels with flowers, scrolls, and a bird.

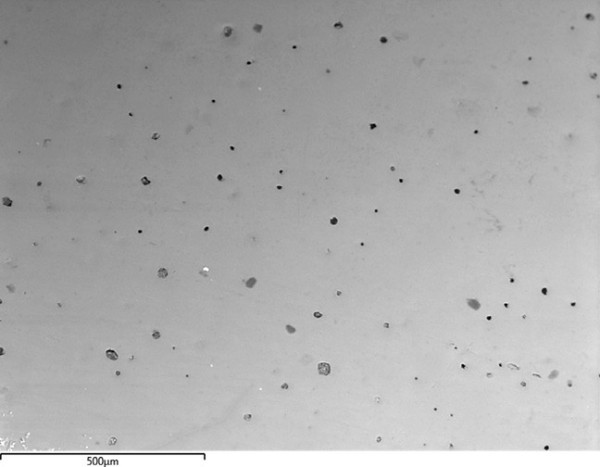

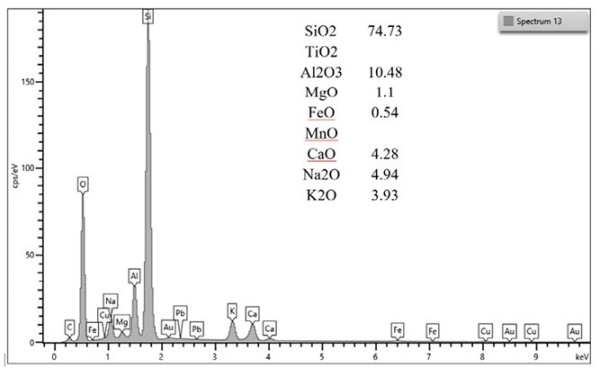

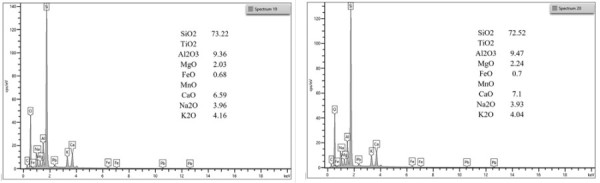

Image of glaze surface analyzed for Spectrum 13 on the snuff box.

Analysis for the glazed surface illustrated in fig. 17 with analysis (wt%) provided in top right. Gold (0.82 wt% Au2O3), copper (0.34 wt% CuO), and lead (0.53 wt% PbO)—regarded as contaminants—have been removed and the resultant analysis summed to 100%.

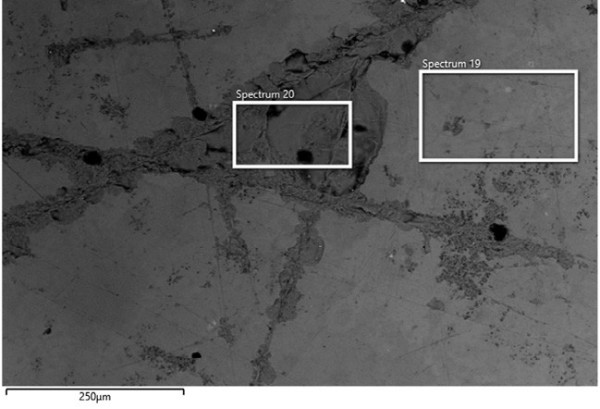

Image of the glaze surface on the base of the snuff box analyzed for Spectra 19 and 20.

Spectra 19 and 20 generated from the glazed base of the snuff box. For both analyses lead was regarded as a contaminant and removed. The resultant analyses were then been summed to 100 wt% and the values reproduced in the top right of both figures in wt%.

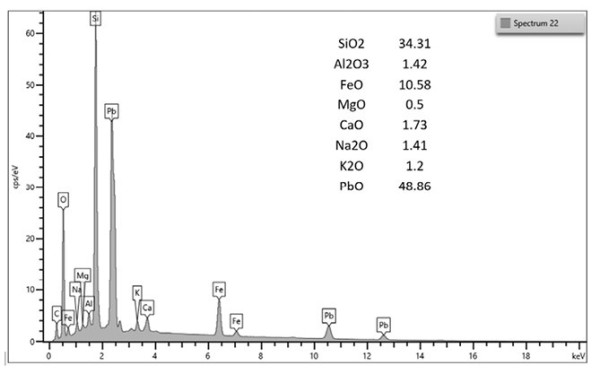

Spectrum 22 of red enamel at the edge of the snuff box rim showing a high lead (48.9 wt% PbO) and silica (34.3 wt% SiO2) and prominent iron (10.6 wt% FeO).

AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY porcelain ceramic snuff box came up for sale at a leading auction house in London in 2012. This box had been previously attributed to the Italian factory of Doccia, but at this sale, based on the shape of the box and a scan of the glaze acquired using a handheld X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzer, the item was reattributed to the small group of A-marked porcelains now attributed to the 1744 patent of Edward Heylyn and Thomas Frye and, by implication, to the Bow porcelain manufactory. A feature of this scan was the prominent peaks in the spectra for lead, an element not associated with the A-marked group. The body, glaze, and on-glaze enamels for this snuff box have now been nondestructively reanalyzed using JEOL JSM-IT200 scanning electron microscope (SEM) and quantitative Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDX) system and the data are presented and discussed. The lead previously reported in the glaze is shown to be surface glaze contamination. Based on body and glaze compositions the conclusion is that this box conforms to the 1744 patent specification and hence is attributable to the high-fired A-marked group of English porcelains.

Background of the A-marked Porcelains Group

A small group of porcelains known as the A-marked porcelains or 1744 patent porcelains was first recognized on December 14, 1937, at the Albemarle Club, London, when four items were discussed at a meeting.[1] No agreement was reached as to the group’s attribution, however. Subsequently, Arthur Lane assembled seven objects from this group and conferred on them the name “A-marked.”[2] Lane noted that the porcelain body was much harder than typical English soft-paste porcelains and he proposed that their bodies were of a “hybrid” type containing some kaolin clay. This hardness of the body once led some to suggest a continental origin but a paper by Robert J. Charleston and John V. G. Mallet established that this group was British in origin.[3] Subsequent research has confirmed that these porcelains conform to the 1744 patent specification of Edward Heylyn and Thomas Frye, and that the key ingredient of that specification was the so-called Cherokee clay imported from the Carolinas of America. The 1744 patent specified the use of a clay, “an earth, the produce of the Chirokee nation in America, called by the natives unaker.”[4]

Ruthie Dibble and Joseph Zordan have recently emphasized the importance of this white clay to the Cherokee people having aesthetic, spiritual, and relational values and they claim the clay to have an inalienable kinship with the Cherokees.[5] A summary of this group of porcelains now comprising some forty members and made from this white clay, has been just published in 2022.[6] This latest account provides an outline of the history of these A-marked porcelains, their various attributions proposed over time, and a summary of all published analyses of this group—both body and glaze. These authors concluded that the A-marked porcelain group can now be regarded as arguably the first fully commercial ‘hard-paste’ porcelain wares to have been produced in mid-eighteenth-century England and, quoting a commentator, they noted that as a corollary there needs to be a reassessment of the assumed premier position of the Chelsea Porcelain Works.

Initial Examination of the Snuff Box

The snuff box with a gilt-metal mount is illustrated in figures 1–5 and measures 1 7/8 x 2 1/2 x 2 3/8 inches. A detail of the bottom, illustrated in figure 6, shows use-wear to the enameled decoration as might be expected. Initially assumed to be unmarked, when examined by co-author Manners, an indistinct incised “A” mark in the interior of the bottom was observed. This mark had been overlooked or unrecorded. When subsequently photographed in raking light using a polarizing filter on the camera to minimize glare, the incised “A” becomes much more apparent (fig. 7). In this present account the body, glaze, and on-glaze enamels of the porcelain snuff box are examined nondestructively—and a firm attribution to the A-marked group of porcelains is made.

The snuff box is one of three that can be attributed to the A-marked group, which has long intrigued ceramic scholars. All three are of near identical form and size and have the same gilt-copper hinged mounts, but each is decorated differently. The box under discussion is painted with merchants and ships in harbor scenes in the Meissen “Kauffahrtei” style. Similar decoration of castellated towers, casks, and barrels by the same hand is also found on the cover of a box in the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff (fig. 8). A third box, sold by Stockspring Antiques in 2012 and now in the Peter and Mary White collection, is painted with a butterfly and fruit (fig. 9). All three boxes use the same basic palette of brown, green, purple, blue, yellow, and iron-red to different effect.

The Cardiff snuff box also has an indistinct incised mark that has been read as an A. Likewise, elements of the decoration, notably the iron-red scroll work of the Cardiff box and the fruit garlands of the Stockspring/White example link them to marked High Style teawares of the A-marked group. The term High Style was introduced by Charleston and Mallet to differentiate the more painterly wares of the A-marked group from the simpler stock patterns.[7]

The treatment of the iron-red rococo scrolls and lion head mascarons on the Cardiff box can be matched to the cartouche scrolls on two A-marked teapots in the Victoria and Albert Museum and are most likely by the same hand (figs. 10, 11). The scrolls and mascarons follow closely the borders in the engraving by Jacques Bachelet after Hubert-François Gravelot of Le Jeu de la Crosse and in the engraved sheet, “The Second part of Youthful Diversions, published according to Act of Parliament 7th May 1739,” which is the source for decoration on other members of the A-marked wares.[8] The bunches of fruit on the box in the private collection (see fig. 9) match the fruit falling from the cornucopia on the unique cane handle located by Elizabeth Adams and now in the Victoria and Albert collections (fig. 12). The iron-red shell and small figures on the cane handle can, in turn, be closely linked to the two teapots.

The box illustrated in figure 2 was once in an Italian collection acquired through the Rome dealers Lukacs-Donath in 1966, who often bought in London.[9] It was then mistakenly published as Doccia, as the paste does bear some similarity. It was correctly identified by Nette Megens of Bonhams, London, in 2011, as belonging to the A-marked group because of its close similarities in shape with the Cardiff box. Tests carried out by Kelly Domoney and Prof. Andrew Shortland of Cranfield University with a SEA6oooVX mapping XRF confirmed that the glaze matched the Cardiff box and differed from Doccia.[10] However, in a discussion on these glaze spectra Ramsay and Ramsay questioned the high lead levels reported, and argued that such glaze compositions are not in accord with the 1744 patent specification of Heylyn and Frye.[11] Consequently, it was decided to reanalyze this snuff box—body, glaze, and enamels—at Brunel University on March 14, 2022, through the courtesy of Dr. Ashley Howkins.

Analytical and Technical Background to Analyses at Brunel University

SEM imaging was carried out using a JEOL JSM-IT200 SEM, and quantitative EDX analysis was carried out using an Oxford Xplore 15mm2 EDX detector with accompanying Aztec software (fig. 13). The SEM was operated under low vacuum conditions, 30-60Pa, with an accelerating voltage of 20kV, which enables charge-free imaging. EDX analysis was done with a minimum count rate of 1,000 counts per second and 30–100s live-time acquisition.

Back-scattered electron images were acquired in compositional and shadowing modes, which enable identification of regions of elemental difference and topography, respectively. Operating the SEM in such imaging modes enabled differentiation of areas of enamel from the glaze, and areas where the glaze had worn away as a result of a rubbing action from the metal rim revealing the underlying porcelain (fig. 14).

Discussion on the Snuff Box Porcelain Body

Fourteen scans of the snuff box—body, glaze, and on-glaze enamels—were undertaken at Brunel University. The box is fully glaze-covered but a glaze-denuded area adjacent to the gold-copper metal collar revealed the underlying porcelain body (Spectrum No. 6). This spectrum is presented in figure 15. Contamination by gold, copper, and/or lead was experienced and in the case of Spectrum 6 gold and copper oxides comprise 5.3 wt% of the analysis (Table 1). Both oxides are regarded as contaminants from the copper-gilt mounts and have been removed with the resultant total being recast to 100%.

Currently there are nine A-marked porcelain body analyses in the literature as summarized in Edwards et al. The body analysis of this snuff box as provided here raises the total to ten.[12] A feature often overlooked in some previous A-marked studies is that there is a wide range of A-marked body compositions. The 1744 patent specification stated that porcelain compositions produced could range from 50 wt% Cherokee clay: 50 wt% lime-alkali bottle glass through to 80:20 wt%. Analyses to date have identified examples of this porcelain group ranging from 50:50 through to 70:30 wt%, but a composition of 80:20 wt% has yet to be identified.[13] The body composition of this snuff box falls within the 50:50 wt% group and two other examples of this type present themselves, namely the two cups investigated by Edwards et al (fig. 16).[14] Comparative analyses of all three are given in Table 1 below.

The results from Spectrum 6 demonstrate that the body of the snuff box was produced according to the specifications of the 1744 Heylyn and Frye patent. Key chemical features of this spectrum that support this conclusion are:

• High Al2O3 at 18.1 wt% indicative of a refractory body.[15]

• Prominent alkali and alkali earth oxide fluxes with CaO > K2O + Na2O.

• Absence or very low levels of the colorant oxides MnO, FeO, and TiO2 whose low levels indicate the apparent use of a primary clay in the porcelain body rather than a secondary clay.[16]

• The level of MgO (2.02 wt%) is higher in this snuff box than recorded for the two cups and this is assumed to reflect higher MgO in the lime-alkali glass cullet used for the box.

• Virtual absence or very low levels of P2O5 and PbO. This absence of lead or very low levels in both body and glaze is a characteristic feature of the A-marked group.[17] This feature suggests that the proprietors bought in ‘job lots’ of lime-alkali glass cullet contaminated with minor amounts of flint glass.

• Cup 2 recorded the presence of cassiterite (SnO2) in the body (Table 1).[18] This was not recorded in the snuff box.[19]

Discussion on the Snuff-Box Glaze

For the purposes of this discussion on the glaze composition of the snuff box, the following spectra captured by Brunel University, 7, 13, 19, and 20 (figs. 17–20) are used. In addition, the glaze compositions obtained for A-marked Cups 1 and 2 are reproduced, along with the calculated theoretical glaze composition based on a porcelain body with 50 wt% Cherokee clay and 50 wt% lime-alkali bottle glass as derived from the 1744 Heylyn and Frye patent specification.[20]

A feature of all three Brunel University glaze scans, coupled with a fourth (Spectrum 7, Table 2), is that they have been contaminated to varying degrees with Au, Cu and/or Pb. In each case this contamination has been subtracted and the analysis recast to total 100 wt%. These recast analyses are shown in Table 2 to the right of each initial Brunel analysis. It should be noted that the glaze compositions for Cups 1 and 2 do have very low PbO levels, thought to reflect the contamination by small amounts of flint glass. For this discussion, the lead values recorded—together with those for copper and gold in the three Brunel University spectra—have been removed.

Key features of the Brunel University glaze scans are:

• The distinctly aluminous composition of the glazes in all four scans with Al2O3 varying from 9.36–11.57 wt%.

• The high levels of the alkali and alkali earth oxides with typically CaO ~ K2O + Na2O, with the exception of Spectrum 13 where CaO = 4.28 and K2O + Na2O = 9.22 wt%.

• Total alkali and alkali earth oxides (K2O + Na2O + MgO + CaO) are high ranging from 14.25–17.31 wt%.

• Absence of significant lead (PbO) from the glaze analyses.

Those features are likewise reflected in the theoretical glaze composition and in the analyses of two A-marked cups (see Table 2). The conclusion reached is that the glaze composition found on this snuff box is of the high-fired Si-Al-Ca glaze type, first developed in Britain apparently by John Dwight in the 1670s and brought to perfection in the 1744 patent specification of Heylyn and Frye.[24] These results lend further support to the claim that this snuff box conforms to the specification contained in the 1744 patent.

Discussion of the On-Glaze Enamels

A range of pigmented sites were analyzed on the lid and side of the snuff box: these comprised red, brown/black, purple and green regions. There was no evidence of a blue, orange, or yellow pigment usage on the snuff box. The most characteristic general feature of the pigments analyzed here was the presence of significant signals for lead and silica in all. The former did not appear in the glaze or body of the specimen, which strongly indicates that a lead-rich powdered glass, predominantly chemically a lead silicate, PbSiO3, was used to compound the pigment prior to its application. It is noteworthy that the surrounding glaze and body substrate are both very low in lead signals. The four pigmented areas studies will now be considered individually with their major elemental oxide components:

RED

Two areas were sampled, one was the red flag borne by the ship (see fig. 2) and the other a red area at the rim base. The former region, the red flag represented by Spectrum 10 (not illustrated), shows an elemental composition of lead 31%, silica 47%, and iron 11%. This clearly can be assigned to haematite, Fe2O3. A minor trace of copper at 0.4% present could possibly signify the inclusion of a small amount of cuprous oxide, Cu2O, which being brown in color would give a more subdued tone to the red pigment used at this site.

The second red area at the edge of the basal rim, represented by Spectrum 22 (fig. 23), again shows a lead-rich composition at 48.9% and silica at 34.3%, and with a similar iron content at 10.6%. There is no trace of a copper signal found in this area. The assignment to haematite for this pigment is also proposed.

PURPLE

Located on the seated gentleman’s purple coat on the lid (see fig. 1), Spectrum 18 (fig. 22), with high lead at 47.2% and silica at 38.5%, the other significant elemental percentages are gold at 2.6%, tin at 2% and iron at 1 wt%. The combination of gold and tin together is indicative of the use of a purple of Cassius pigment, which is basically a colloidal gold precipitated onto tin oxide particles. Named after Andreas Cassius of Hamburg, who discovered the pigment in 1666, its preparation involved the reduction of chloroauric acid (formed from the dissolution of gold in aqua regia) by stannous chloride (tin II)—the atomic gold particles being colloidally dispersed onto the oxidized stannic oxide particles (tin IV). The depth of color produced is dependent on the amount of gold present; here, the pale purple color would reflect a smaller amount of gold perhaps being used in the pigment preparation. The presence of iron at around 1% could be a contamination from the pigment preparation itself or perhaps indicative of the use of the purple iron pigment, caput mortuum, as a diluent to achieve a particular tonal shade of purple. Caput mortuum, a purple nodular form of haematite mineral with the chemical formula Fe2O3, was sourced since Roman times in Britain at the Clearwell Caves in the Forest of Dean and was much admired for its purple color.

GREEN

The large area of green on the lid and side of the specimen, represented by Spectrum 16 (fig. 23), with lead at 46.5%, silica at 38%, and copper at 5% and iron at 3%, is indicative of the use of verdigris, basic copper acetate Cu(OH)2. Cu(CH3CO2)2 and terre verte, a green earth of complex formulation represented chemically by K(AlFe3+)(Fe2+Mg)AlSi7O10(OH)2. The former was prepared by the immersion of thin copper sheets in stale wine (vinegar), whereas the latter originated from the minerals celadonite and glauconite: the most desirable but expensive and pure form of celadonite green earth pigment was sourced in Monte Baldo, Lake Garda, Italy. The presence of the copper and iron elemental signatures in the green pigment on the snuff box indicates that potentially a mixture of green earth and verdigris was used.

BLACK

The black area, represented by the ship’s mast in Spectrum 14 (fig. 24), is described visually as having a brownish-black tone, again with a high lead content at 31.4%, silica at 40%, and with iron at 8.7% and copper at 7%. The combination of copper and iron indicates a mixed pigment composition based on black magnetite, Fe3O4, and black cupric oxide (tenorite) CuO, which are both available as minerals geologically. Magnetite (Mars black) was a popular black pigment used as an alternative to carbon black and ivory black, which were absent here in the specimen being studied. The hint of a brown color could have been achieved by the incorporation of brown cuprous oxide, Cu2O, or possibly the brown-colored mineral plattnerite PbO2, whose presence would be masked by the high lead signal from the background lead silicate.

The absence of synthetic pigments that are associated chronologically with later periods of decoration and porcelain manufacture is to be noted and this indicates that the snuff box has not been retouched or restored using these in modern times. In particular, the use of the strong pigments favored in the nineteenth century for the colors—such as cadmium sulfide red, pyrolusite manganese black, viridian chrome green, and synthetic ultramarine blue in admixture with iron Mars red for purple—are noteworthy for their absence.

Doccia Porcelain Factory

In 1737 marchese Carlo Ginori established the Ginori porcelain factory in Doccia, near Florence where Ginori apparently experimented with a variety of clays.[25] The snuff box under discussion first appeared in a publication by Barbara Beaucamp-Markowsky in which the box is illustrated and attributed to Doccia.[26] In its catalog for the sale of the snuff box, Bonhams recorded this entry by Beaucamp-Markowsky and noted that it was attributed to Doccia by that author.[27] Aniko Bezur and Francesca Casadio recently carried out two analyses of Doccia porcelains, which appear to be refractory judging by their aluminous bodies (Table 3).[28]

Although the use of a handheld XRF prevented the recognition of both Na2O and MgO in the Doccia porcelains, the plotting of K2O vs CaO (fig. 25) does allow the separation of this snuff box from Doccia porcelains, which are characterized by a potassic flux. The high level of CaO in the snuff box shown in the shaded blue area allows for its inclusion within the field of A-marked porcelains.

The Use and Abuse of Nondestructive Analyses of Porcelains

Although the necessity of the provision and inclusion of chemical analytical data in the attribution of porcelains to factory sources is deemed essential for the holistic forensic assessment to be carried out, it is clear that this approach must be undertaken with the proper protocols and an appreciation of the pitfalls that can entrap the unwary. In the related field of oil paintings, it is now established practice that important works of art are accompanied by the appropriate scientific analytical data to assist in their assignment to specific artists and to chronological periods, along with historical provenance, previous ownership reference, documentation, and connoisseurship. The latter refers particularly to the opinion of established experts who have spent many years studying the artistic style and palette of the artists, their techniques, and their usage of pigments and materials in the creation of their artworks. The holistic approach that has seen the adoption of chemical and physical analysis as a de rigueur requirement for attribution of oil paintings has revealed the significance of potential errors that have been made historically where connoisseurship alone has been found sadly wanting: in a recent publication that accompanied the exhibition “Close Examination: Fakes, Mistakes and Discoveries,” Marjorie Wieseman cited seven paintings from sixteen studied, apparently all genuine on the basis of connoisseurship opinion alone, which had to be downgraded to copies and fakes when scientific analytical data were incorporated, representing a significant 44% of misattributions.[29]

A similar situation could certainly exist for the attribution of porcelain specimens from unknown factory sources unless the incorporation of analytical scientific data is recognized for the holistic assignment of ceramic works of art. The major difference between the analytical studies that are undertaken for oil paintings and those for porcelains is that the former can be undertaken on small specimens of pigment that can be excised prior to restoration and conservation of a painting. In contrast, the removal of small specimens of glaze, pigment, or body from a ceramic specimen is normally strongly disfavored, which means that nondestructive analytical techniques are necessary, as used in this study.

The nondestructive chemical analytical techniques that usually are applied to ceramics are SEM/EDAXS, spectroscopy, and XRF spectroscopy (for the elemental composition) and Raman or FTIR spectroscopy for the molecular composition. The elemental composition as undertaken by SEM/EDAXS involves the acquisition of data from micro-regions with a footprint of some hundreds of nanometers and multiple replicate sampling is usually undertaken to account for specimen inhomogeneity.

The limitation of the SEM/EDAXS technique is the finite size of the sample chamber of the instrument used, which requires evacuation or low-vacuum to avoid applications of a coating of carbon or gold on the sampling region. Therefore, large ceramic items are not usually accessed in this way; the technique of choice becomes portable XRF spectroscopy, which uses miniaturized instrumentation to access the specimen. A particular disadvantage of XRF spectroscopy (or handheld XRF) is that the intensity of the analytical signal is dependent on the atomic number of the element concerned so that lighter elements with low atomic numbers, such as carbon, boron, oxygen, sodium, and magnesium, are often not detectable. It is commonly found that the limit of detection by portable XRF spectroscopy is shown to be at the limit of sodium (atomic number 11) and magnesium (atomic number 12). Both techniques are qualitative and quantitative in the analytical data that are obtained.

Raman and FTIR spectroscopy are surface techniques and need access to appropriate regions of the specimen for analysis to be performed, which usually can be undertaken using remote probes and offset image acquisition devices. Rarely is it desirable or necessary to remove a sample from an undamaged porcelain artifact to undertake analysis unless this can be achieved without detriment to the object concerned—and indeed most collectors and museum curators would not entertain this except in the most critical of cases for which the analytical data would be expected to provide definitive results. It is a rather different scenario, of course, with damaged ceramics for which the removal of a sample would not be viewed as compromising the integrity of the artifact, and for sherds that have been recovered from the archaeological excavation of porcelain manufactory waste pits.

The criteria operating for the chemical analysis of porcelains, therefore, should be enumerated as follows:

• Has the correct analytical technique and associated procedure been adopted to determine the appropriate data and parameters? For instance, if the determination of sodium oxide (Na2O) and magnesium oxide (MgO) are adjudged to be critical and XRF has been the analytical technique used, it is unlikely that the analytical data detection limits will be acceptable.

• If the important data set refers to the detection of elements derived from raw material impurities or from minor additives that have been noted in the formulations and recipes of porcelain manufactories then the detection limit(s) of the techniques adopted are vitally important. It is pointless using handheld XRF to determine the presence of boron that has been derived from the addition of borax to the body paste formulation because it is too light an element (atomic number 5) to be detected. It is equally important that the presence of minor heavy metals or elements such as titanium, sulphur, and cobalt are recognized and not ignored since they can be extremely useful in determining the geographical source of raw materials or whether minor additions of gypsum, alum, or smalt have been made to the porcelain paste formulation. In particular, the presence of certain elements in pigments, for example, can be related to the chronological usage of specific pigments by the manufactory concerned. This can be invaluable for the chronological placement of the enameling decoration on a porcelain artifact; it is especially important for the analytical detection of fakes and later additions to the decoration. Certain pigments were used historically by manufactories over narrow periods of production timelines, and that information can be useful for the correct placement of a piece chronologically. In the snuff box under discussion, the absence of such compounds as cadmium sulfide red, pyrolusite manganese black, viridian chrome green, and synthetic ultramarine blue in admixture with iron Mars red for purple indicate that the enamels used predate the nineteenth century.

• The nondestructive spatial interrogation of a ceramic specimen must be accomplished with reference to the primary objective that is being sought in that particular scenario: is the experiment designed to analyze the pigment composition, the glaze, or the body paste? This calls upon the analyst to select the proper sites for the analytical determination to be accomplished, so that the results obtained are meaningful. For example, it is not acceptable to attempt to analyze the body paste through the glaze unless one is certain that the glaze compositional data are also not being interrogated simultaneously in the process, which would then compromise the data set. It is clear that, for example, a lead-rich glaze being interrogated along with ostensibly a body paste determination could lead to the erroneous conclusion that the body paste itself also comprised a significant contribution from a lead additive, such as flint-glass cullet or various oxides of lead.

• Replicate data sets are necessary to assist the interpretation of inhomogeneous specimens, which most ceramics are in microscale; there could be regions that are rich in particular elemental composition which do not reflect the bulk material as a whole.

• The most significant aspect of an analytical determination, however, is the interpretation of the elemental or molecular data sets obtained in the light of existing documentation relating to the manufactory procedures and usage of raw materials. Unfortunately, much historical information of this kind has been lost or was simply never recorded in the first place. Equally important is the realization that manufactory proprietors were generally empirical experimentalists, and in the few cases where their notes have survived, it is very revealing to experience their attempts to improve the perceived deficiencies in their porcelain output with impromptu changes made to their body paste or glaze formulations to achieve a better compatibility of product.

What is clear is that all components of the holistic appraisal of porcelain for attribution purposes must be verified; otherwise, one or more might be accredited falsely as being of importance when in fact it is suspect in its origins. As regards analytical data, this means that the determinations have been carried out effectively and reliably so that the compositional data can assuredly and uncompromisingly be related to the body paste, the glaze, or the enamel pigments from which evidential interpretation can then be forthcoming. The same criteria must also apply to the reliability of provenancing documentation and its matching to the art work under study, including notes and information relating to the formulations and recipes used at the manufactory. In addition, connoisseurship opinion based on stylistic considerations, is invariably reliant on access to standard exemplars purportedly originating from the manufactory for comparative assessment. In this case the specification contained in the 1744 patent of Heylyn and Frye has been critical in recognizing the source and attribution of the A-marked porcelain group. Above all, as in the case of oil paintings, it would be facile to dismiss the analytical data as irrelevant or weak solely because they do not conform to established opinion about an art work that has evolved historically, often with little other evidentiary support.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We acknowledge the Victoria and Albert Museum for permission to publish the images of two A-marked teapots in their collection and the cane handle. We also thank the National Museum of Wales for two images of their A-marked snuff box, and a private collector for permission to publish an image of the Stockspring snuff box.

Mrs. L. Wilson, “A Miscellany of Pieces: Report of a Meeting Held at the Albemarle Club onDecember 14th, 1937,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 2, no. 7 (1939): 83.

Arthur Lane, “Unidentified Italian or English Porcelains: The A Marked Group,”Mitteilungsblatt (Keramik Freunde der Schweiz), no. 43 (1958): 15–18.

Robert J. Charleston and John V. G. Mallet, “A Problematical Group of Eighteenth-Century Porcelains,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 8, no. 1 (1971): 80–121.

Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, A.D. 1744: Manufacture of Earthenware, Heylyn and Frye’s Specification, Patent No. 610 (London: HMSO, 1856), pp. 1–3; Ian C. Freestone, “‘A’-Marked Porcelain: Some Recent Scientific Work,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 16, no. 1 (1996):76–84; W. R.H. Ramsay, Anton Gabszewicz, and E. Gael Ramsay, “Unaker or Cherokee Clay andIts Relationship to the ‘Bow’ Porcelain Manufactory,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 17,no. 3 (2001):473–99; W. R.H. Ramsay, Anton Gabszewicz, and E. Gael Ramsay, “The Chemistryof ‘A’-Marked Porcelain and Its Relation to the Heylyn and Frye Patent of 1744,” English Ceramic Circle Transactions 18, no. 2 (2003): 264–83; W. R.H. Ramsay, Judith A. Hansen, and E.Gael Ramsay, “An ‘A-Marked’ Covered Porcelain Bowl, Cherokee Clay, and Colonial America’s Contribution to the English Porcelain Industry,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2004),pp. 60–77; W. R.H. Ramsay, Frank A. Davenport, and E. G. Ramsay, “The 1744 Ceramic Patent ofHeylyn and Frye: ‘Unworkable Unaker Formula’ or Landmark Document in the History of English Ceramics?,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 118, no. 1 (2006): 11–34; W. R.H.Ramsay and E. G. Ramsay, “A Classification of Bow Porcelain from First Patent to Closure: c.1743–1774,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 119, no. 1 (2007): 1–68; Pat Daniels,The Origin & Development ofBow Porcelain, 1730–1747: Including the Participation of theRoyal Society, Andrew Duchè and the American Contribution (Oxon, U.K.: Resurgat, 2007).

R. Ruthie Dibble and Joseph Mizhakii Zordan, “Cherokee Unaker, British Ceramics, and Productions of Whiteness in Eighteenth-Century Atlantic Worlds,” British Art Studies 21 (2021): https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-21/dibblezordan.

Howell G. M. Edwards, William H. Jay, and W. Ross H. Ramsay, “High-Fired Early English Porcelains of the ‘A’-Marked Group, East London (c. 1744): A Raman Spectroscopy and Electron Microscopy Compositional Study,” Journal Raman Spectroscopy 53, no.4 (2022): 785–809.

Charleston and Mallet, “Problematical Group of Eighteenth-Century Porcelains.”

Ibid.; Daniels,Origin & Development of Bow Porcelain, 1730–1747.

Collezione Procida Mirabelli di Lauro, Naples, no. 67. Acquired from Lukacs-Donath in 1966,Bonhams, April 18, 2012, lot 168.

Bonhams, Fine British Pottery, Porcelain & Enamels, sale cat., April 18,2012 (London:Bonhams, 2012), lot 168.

W. R.H. Ramsay and E. Gael Ramsay, The Evolution and Compositional Development of English Porcelains from the 16th C to Lund’s Bristol c. 1750 and Worcester c. 1752—The Golden Chain (Invercargill, N.Z.: [Ross Ramsay], 2017), Appendix 3.

Edwards, Jay, and Ramsay, “High-Fired Early English Porcelains of the ‘A’-Marked Group,East London (c. 1744).”

Ibid.

Ibid.

W. R.H. Ramsay, G. R. Hill, and E. Gael Ramsay, “Re-creation of the 1744 Heylynand FryeCeramic Patent Wares using Cherokee Clay: Implications for Raw Materials, Kiln Conditions, andthe Earliest English Porcelain Production,” Geoarchaeology 19, no. 7 (2004): 635–55.

Freestone, “‘A’-Marked Porcelain”; Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “Chemistry of ‘A’-Marked Porcelain.”

Freestone, “‘A’-Marked Porcelain”; Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “Chemistry of ‘A’-Marked Porcelain”; Ramsay, Hansen, and Ramsay, “An ‘A-Marked’ Covered Porcelain Bowl”; Ramsay, Hill, and Ramsay, “Re-creationof the 1744 Heylyn and Frye Ceramic Patent Waresusing Cherokee Clay”; Ramsay, Davenport, and Ramsay, “1744 Ceramic Patent of Heylyn and Frye.”

Edwards, Jay, and Ramsay, “High-Fired Early English Porcelains of the ‘A’-Marked Group,East London (c. 1744).”

However, see Freestone, “‘A’-Marked Porcelain.”

Edwards, Jay, and Ramsay, “High-Fired Early English Porcelains of the ‘A’-Marked Group,East London (c. 1744)”; Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “Chemistry of ‘A’-Marked Porcelain.”

Ramsay, Gabszewicz, and Ramsay, “Chemistry of ‘A’-Marked Porcelain.”

Edwards, Jay, and Ramsay, “High-Fired Early English Porcelains of the ‘A’-Marked Group, East London (c. 1744).”

Ibid.

Ramsay and Gael Ramsay, Evolution and Compositional Development ofEnglish Porcelains.

Andreina d’Agliano, “The Ginori Porcelain Factory in Doccia,” in Fascination of Fragility: Masterpieces of European Porcelain, edited by Ulrich Pietsch and Theresa Witting (Dresden:Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, 2010), pp. 78–87.

Barbara Beaucamp-Markowsky,Porzellandosen des 18. Jahrhunderts (Munich: Klinkhardt &Biermann, 1985), no. 476, p. 518.

Bonhams, Fine British Pottery, Porcelain & Enamels, sale cat., April 18, 2012 (London:Bonhams, 2012), lot 168.

AnikoBezur and Francesca Casadio, “Du Paquier Porcelain: Artistic Expression andTechnological Mastery, a Scientific Evaluation of the Materials,” in Fired by Passion: ViennaBaroque Porcelain of Claudius Innocentius Du Paquier, edited by Meredith Chilton, 3 vols.(Stuttgart: Arnoldsche, 2009), 3:1165–1211.

Marjorie E. Wieseman, A Closer Look: Deceptions and Discoveries (London: National Gallery,2010).