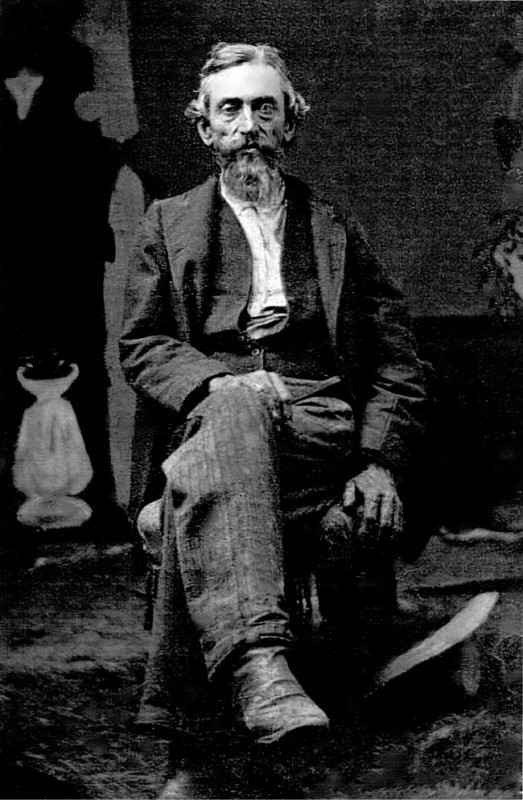

Photograph of John Wesley Carpenter (1842–1913), ca. 1880–1885. (Courtesy of the Carpenter family.)

Jug, attributed to Wade D. C. Johnson (1850–1931), Catawba County, North Carolina, ca. 1880–1900. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 13 1/4". Mark: incised “W J” four times. (Courtesy, Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society.)

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 2.

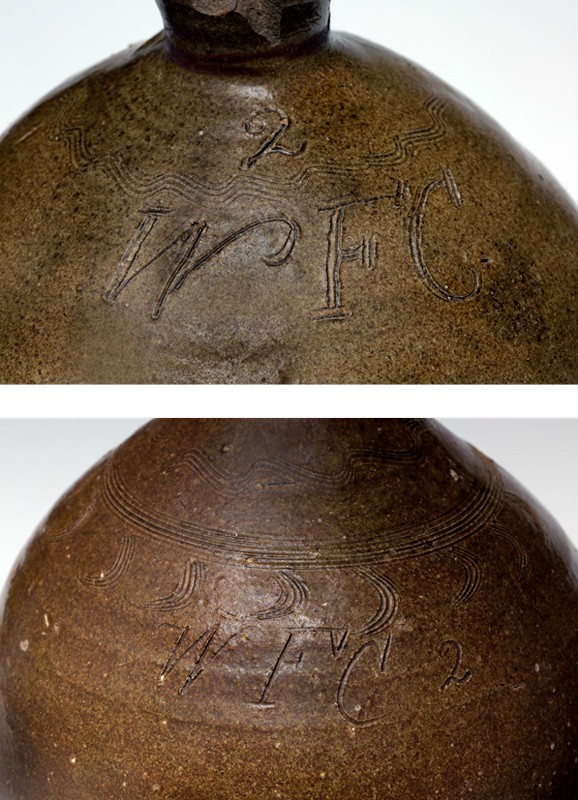

Details of the jugs illustrated in fig. 8, both inscribed “WFC” and “2”.

Genealogical chart showing the interrelationship between several pottery-making families, among them Carpenters, Johnsons, and Ritchies.

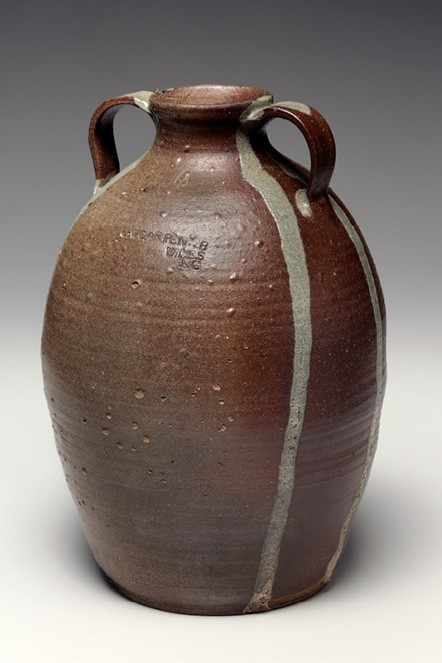

Six-gallon jug, J. W. Carpenter Pottery, Wiles, Wilkes County, North Carolina, ca. 1890. Salt-glazed stoneware with glass runs. H. 17 3/8". Mark: “J.W. CARPEN[TE]R / WILES / NC” (Courtesy, Wilkes Heritage Museum, Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) Long presumed to be associated with John Wesley Carpenter, this late-nineteenth-century pottery shop was owned and operated by James Welborn Carpenter. No family relationship between the two potters is known.

Six-gallon jar with four lug handles, attributed to J. W. Carpenter Pottery, Wiles, Wilkes County, North Carolina, ca. 1890. Salt-glazed stoneware with glass runs. H. 16 1/2". Mark: “6” (William C. and Susan S. Mariner Collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Two-gallon jugs, attributed to William Franklin Carpenter, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1873. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. Left: H. 13".

Marks: incised “WFC” and “2” (Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society Collection.) Right: H. 12 1/2". Marks: incised “WFC” and “2” (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Five-gallon jug, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with glass runs. H. 16 1/2". Mark: incised “JWC 5” (Courtesy, Wilkes Heritage Museum, Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) Opposite the signature are inscribed additional indecipherable letters/numerals. This jug, and other wares signed “JWC” in script, were probably made by Carpenter in Lincoln County, North Carolina, prior to his relocation to Pipers Gap, Virginia.

Two-gallon jug, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". Mark: incised “JWC 2” (Courtesy, Wilkes Heritage Museum, Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Half-gallon jug, Thomas Ritchie Pottery, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, second half of the nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". Mark: “TR 2” (J. M. Cline Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) This jug’s resemblance to the one attributed to John Wesley Carpenter in fig. 10—especially its tapered, fine-line reeded spout neck—suggests that Carpenter made it while working for Ritchie.

One-gallon jug, attributed to the John Wesley Carpenter pottery shop, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/4". Mark: incised “JWC 1” (numeral formed by a vertical series of dots). (Courtesy, Wilkes Heritage Museum, Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) This jug’s form differs enough from the one in fig. 10 to suggest that a different potter was engaged in its production for John Wesley Carpenter’s shop.

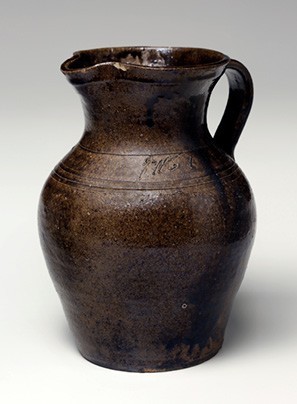

One-gallon pitcher, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 9 3/4". Mark: incised “JWC 1” (Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) The handle has been restored.

Two-gallon storage jar, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/4". Mark: incised “JWC 2” (John Haynes Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Four-gallon storage jar, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 13". (Carpenter Family Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) This jar was recovered from an abandoned cellar situated below a chicken coop on the John Wesley and Emily Carpenter farm. The Carpenter pottery shop in Pipers Gap made salt-glazed and alkaline-glazed stoneware.

Four-gallon jug, Daniel Seagle, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with reeded spout neck and glass runs. H. 16". (Ackland Fund, Ackland Art Museum, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 82.19.2; photo, Jason Dowdle Photography.)

Jug, David Hartzog, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1830–1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with glass and iron slip runs. H. 12 7/8". Mark: stamped “DAVIDHARTZOGHIMAKE” (The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts [MESDA] at Old Salem, 5812.)

Reverse view of the jug illustrated in fig. 17, showing the glass run from the handle.

Three-gallon jug, Thomas Ritchie Pottery, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, second half of the nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 14 5/8". Mark: “TR 3” (Robert and Beverly Simpson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) The jug has incised bands of decorative straight and wavy lines similar to those seen on numerous Carpenter pottery wares.

Pan, attributed to Thomas Ritchie Pottery, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, third quarter of the nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware, H. 7", D. of rim 16". (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) This pan was ostensibly used by a Catawba Valley church for a Christian foot-washing ritual. Its form (especially its rim and handles) and decorative style suggest that John Wesley Carpenter was its maker, at his own or at Ritchie’s Catawba Valley shop.

Four-gallon storage jar, attributed to Thomas Ritchie Pottery, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, second half of the nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 12". Multiple marks, on handles: “4” (Robin and Kem Roberts Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) A stamped four-gallon mark used by John Wesley Carpenter is similar. The horizontal rim form, handle shape, and decoration are similar to what is observed on some John Wesley Carpenter wares.

Bottle, attributed to Marcus Ritchie (ca. 1851–1883), Catawba County, North Carolina, ca. 1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10 13/16". Mark: inscribed “M” (Danny Richard Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) The style of the letter M matches an “MR” signature inscribed on a line-decorated storage jar dated 1882 (not shown). Marcus was the son of Thomas Ritchie (1825–1909).

Two-gallon jug, attributed to Marcus Ritchie, Catawba County, North Carolina, dated 1882. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16". Marks: inscribed “MR / 2” and “1882” (David Parker Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Left: Jug, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. H. 10 7/8". Mark: “JC 1” (L. A. and Suzan Rhyne Collection.) Right: Thomas Ritchie Pottery, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, second half of the nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with multi-line band of incised decoration below neck. H. 14 3/4". Mark: “TR 2” (Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

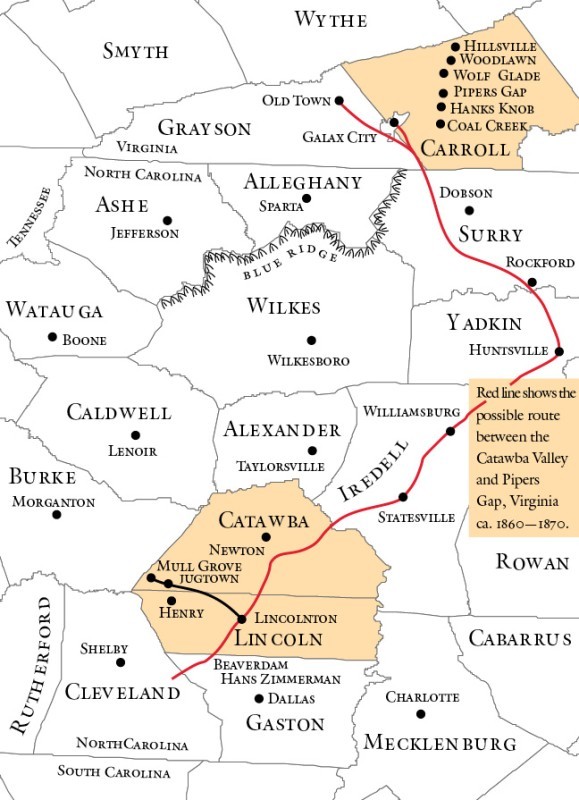

Map showing a conjectured route traveled by Carpenter family members from their Catawba Valley home to Virginia. The route shown was well traveled in the 1860–1870 period. Its path ran east of the mountains and passed through or nearby the town of Huntsville, where Moses Ritchie once resided and probably made pottery, before climbing in its last miles up the Blue Ridge escarpment to Pipers Gap.

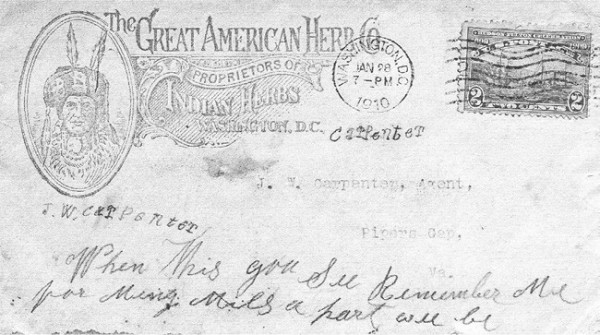

Postal envelope addressed to “J. W. Carpenter, Agent,” from the Great American Herb Company, Washington, D.C., dated January 28, 1910. (John Carpenter Collection.)

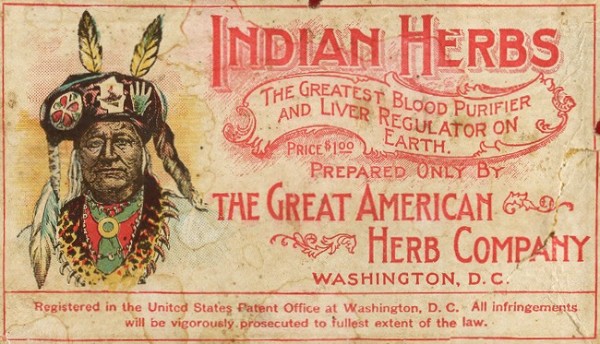

Box lid for Indian Herbs of the Great American Herb Company, Washington, D.C., ca. 1910. (John Carpenter Collection.)

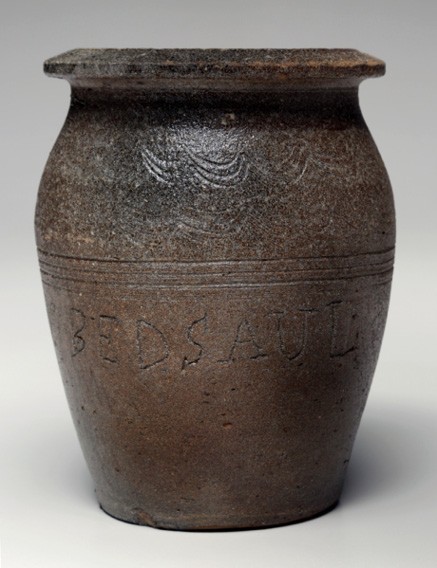

Jar, George Washington Bedsaul (1857–1889), Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, before 1884. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/8". Marks: incised “G. W. BEDSAUL”; incised “H” appears below the rim; and an indecipherable stamped mark, perhaps including the letter B, is impressed on the rim. (Phillip and Deborah Wingard Study Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) This jar’s distinctively sloped rim shape is found on some unsigned jars (see figs. 44, 45), suggesting that they represent Bedsaul’s work as well.

Left: One-gallon jug, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11". Mark: “JC 1” (Wesley Hall Collection.) Right: 1 1/2-gallon cream riser, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/2". Mark, on rim: “JC 1 1/2". (Courtesy, Wilkes Heritage Museum, Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) Some Carpenter salt-glazed stoneware is dark in color, perhaps due to the use of iron-laden clay. Some collectors mistakenly believe it was made in Wilkes County, North Carolina, where salt-glazed stoneware often looks the same. The dark coloration may have led John Wesley Carpenter to add white kaolin slip to greenware before firing it, to lighten its appearance.

Five-gallon jug, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 17 5/8". (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Five-gallon jug, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 17 1/2". Mark: “5” (gallons). (Brian Treverrow Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) A similarly inscribed “5” is found on the signed “JWC” jug illustrated in fig. 9.

Like the treadle wheel with a saddle-like seat used in John Wesley Carpenter’s Pipers Gap shop, this one is being used about 1931 by potter Albert Fulbright (b. ca. 1867) of Lincoln County, North Carolina. By contrast, most of North Carolina’s eastern Piedmont potters stood at the wheel, using a seatless version like those used in the vicinity of Chester County, Pennsylvania, where Quaker and Scots Irish potters prevailed. (Courtesy, Nowell Conan Guffey.)

The ca. 1912–1913 home of John Wesley and Emily Hanks Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Virginia, 2022. (Photo, Stephen C. Compton.) The Carpenter pottery was located nearby, over the hill beyond the house.

Robert Riggins (at left) and his cousin John Wesley Carpenter, great-grandsons of potter John Wesley Carpenter, stand above a pile of soapstone blocks cut by hand a mile away on Hanks Knob. (Photo, Stephen C. Compton.) First used in the construction of a kiln near John Wesley’s original home, they were used to build a chimney for his and his wife’s new house, illustrated in fig. 33. In 1989 remnants of Hurricane Hugo damaged the chimney, which led to its dismantling. The remaining kiln blocks have been stored nearby.

Detail of soapstone blocks once used in the Carpenter kiln. (Photo, Stephen C. Compton.) Close examination reveals evidence of thermal alteration, including deep discoloration, as seen here in a darkened band of stone. Melted kiln arch material has adhered to the edge of the soapstone block. Except for the inclusion of salting ports in its arch, the Pipers Gap kiln was identical to ones used in North Carolina’s Catawba Valley for making alkaline-glazed stoneware.

The Carpenter kiln site as it appeared in 2015. (Photo, January Costa.) A remnant of the large Catawba Valley-styled groundhog kiln extends into the hillside. Rocks, including some soapstone blocks, and bricks, are scattered about in the underbrush. John Wesley Carpenter removed most of the defunct kiln’s soapstone blocks around 1912 when constructing his new home’s chimney.

Storage jar with two lug handles, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, ca. 1868–1912. Stoneware with salt glaze over kaolin slip. H. 16". (Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Storage jar with four lug handles, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware glaze over kaolin slip. H. 17". (Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Four-gallon jug, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware glaze over kaolin slip. H. 15 3/4". Mark: “JC 4” (John Carpenter Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

One-gallon jug, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. H. 11 1/4". Mark: “JC 1” (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Two-gallon storage jar, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. H. 11 7/8". Mark: “JC 2” (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) The vertical line dividing the jar’s slip coating suggests that the jar was dipped horizontally into a larger container filled with a slurry of kaolin slip.

Two-gallon storage jar, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/8". Mark: “JC 2” (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) In addition to salt-glazed stoneware, on special occasions John Wesley Carpenter produced alkaline-glazed stoneware like he once made in North Carolina. That he made both kinds at the same site, and perhaps using the same kiln, likely makes his operation unique among Southern and, more broadly, American potteries.

One-gallon storage jar, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, ca. 1868–1912. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/8". Mark: “JC 1” (L. A. and Suzan Rhyne Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Storage jar, attributed to George Washington Bedsaul, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, 1884. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/2". Mark: “1884” twice on rim. (Colonial Williamsburg Art Museums; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Storage jar, attributed to George Washington Bedsaul, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, ca. 1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with glass runs. H. 9 3/4". (William C. and Susan S. Mariner Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.) The use of glass fragments for decoration is to some extent a common practice among North Carolina’s Catawba Valley alkaline-glaze stoneware makers.

Detail of the storage jar illustrated in fig. 45, showing glass decoration as it was applied to the handles.

Jug, John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, dated 1881. Stoneware with salt glaze over kaolin slip. H. 8". Marks: inscribed “J.W.C.” and “1881” (Carpenter Family Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) Several objects decorated in this fashion are known. In addition to John Wesley Carpenter’s initials and the date, this example includes stylized crosses, a pine tree, and a male figure.

Pitcher, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, ca. 1881. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. H. 7 1/4". Mark: “E. M. Carpenter” (Carpenter Family Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) John Wesley and Emily Hanks Carpenter were married in 1880. This piece displays crosses, pine trees, and a whirligig-type figure. The decorator is unknown.

Pitcher, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, ca. 1881. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. H. 6 7/8". (Wesley Hall Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) This piece displays crosses, a pine tree, and a whirligig-type figure like the one seen on the pitcher illustrated in fig. 48.

Three-gallon storage jar, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, late nineteenth to early twentieth century. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. H. 11". Mark: stenciled “J.W. C. 3” with cobalt smalt. (Carpenter Family Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

One-gallon jug, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, late nineteenth to early twentieth century. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. H. 10 1/4". Marks: stamp-impressed “JC 1”; stenciled “J.C. 1” (Wesley Hall Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Gravestone fragment, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, late nineteenth to early twentieth century. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. 6 x 4 3/4 x 2 3/16". Mark: stenciled “J • C.” with cobalt smalt. (Carpenter Family Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Detail of a four-gallon jar, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. H. 15". Mark: stamped “JC 4” on rim. (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) Harking back to decorations added to Catawba Valley–made alkaline-glazed wares, especially those associated with Thomas Ritchie’s pottery, the Carpenter shop potters often added these combined straight- and wavy-line incised patterns to their pottery. Absent a “JC” or “JWC” mark, such embellishments often reliably substitute for a Carpenter shop signature.

Vessels, attributed to Poley Carp Hartsoe (1876–1960), Catawba County, North Carolina, first half of the twentieth century. Albany slip and alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. of tall jug 11", h. of small jug 3 1/4", h. of pitcher 2 7/8". (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) Even into the early years of the twentieth century, North Carolina’s Catawba Valley potters applied incised line decoration to their vessels’ surfaces. The practice is common among potters associated with the Seagle, Hartzog, and Ritchie family potteries, including members of the Carpenter and Johnson families. Poley Carp Hartsoe was the son of potter Sylvanus Leander Hartsoe (1850–1926) and grandson of potter David Hartzog (1808–1883).

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 9. John Wesley Carpenter knew how adding bits of glass to glazed ware before firing could produce dramatic decorative highlights like this one, seen here in a detail from a masterpiece jug signed with his initials, as if to declare with pride, “I made this.” It seems that he mostly abandoned the practice after moving to Virginia.

Detail of the glass run illustrated in figs. 9 and 55.

THIS ACCOUNT IS ABOUT the eighteenth-century migration of German-speaking farmers and artisans from Pennsylvania to North Carolina’s backcountry, and focuses on one of the families that was affected in immeasurable ways by a nation and state divided by revolution and civil war. It is also the tale of how a member of that family, an entrepreneurial artisan named John Wesley Carpenter, brought new hope and a degree of prosperity to his beleaguered and war-weary family when he journeyed with them from North Carolina to Pipers Gap, Virginia, where he operated a pottery shop, planted orchards, made peach and apple brandy, and peddled herbal medications (fig. 1).[1]

The Carpenters in the Catawba Valley

A scarcity of available tillable land in Pennsylvania led many settlers to migrate to North Carolina during the second half of the eighteenth and the early nineteenth centuries. Perhaps hearing of the Moravians’ successes in North Carolina and the fertile land available there, other German-speaking farmers and artisans moved into the area’s western Piedmont Region to the Catawba Valley section.[2] The Catawba Valley region mainly encompasses Lincoln and Catawba counties, where family names like Crouse, Heafner, Huffman, and Reinhardt remain prominent. Moreover, the Catawba Valley is known among pottery collectors for its uniquely Southern alkaline-glazed stoneware tradition.

One eighteenth-century pioneer who relocated from Pennsylvania to the South Fork of the Catawba River was Hans Zimmerman (ca. 1702–1794). A friend of Moravian bishop August Gottlieb Spangenberg (1704–1792), Zimmerman might have been called John Carpenter in North Carolina, as early American Zimmermans frequently adopted the anglicized name Carpenter to accommodate naturalization.[3] Carpenter family histories suggest that Hans Zimmerman, who was probably Swiss by birth, and his wife, Salome, were John Wesley Carpenter’s earliest North Carolina ancestors.[4]

Hans Zimmerman’s son, Christian “CZ” (a.k.a. Christopher) Carpenter (ca. 1720/22–1800), was active in community affairs, and in 1775 was one of forty-eight Tryon County citizens who signed a document establishing the Tryon Association. Lincoln County was formed in 1779 from a portion of now-defunct Tryon County. The signers of the Tryon Resolves did so in protest of British actions taken earlier in Boston.[5] According to Lincoln County historian William L. Sherrill, CZ Carpenter was among those who strongly advocated American independence.[6] However, the cause of liberty often divided families, and some Carpenters apparently sided with the Tories. Christian Carpenter’s son, John, a British Loyalist, moved to Nova Scotia and later Prince Edward Island after being wounded as a Tory at Ramsour’s Mill.[7] Like his brother John (1742–1816), Christopher (also called Christian and Christy) Carpenter (ca. 1745/50–after 1810) abruptly fled North Carolina sometime after 1779, suggesting that he, too, was a Tory.[8] Christopher Carpenter is John Wesley Carpenter’s great-grandfather through CZ Carpenter and Hans Zimmerman.

About 1830, John Wesley Carpenter’s grandfather “Cumberland” John Carpenter (ca. 1775–after 1850), John Wesley’s apparent namesake and the son of Christopher Carpenter, moved from Lincoln County, North Carolina, to Bedford (later Marshall) County, Tennessee. Before his departure, John’s son Elias (1812–1881) was born in North Carolina. Elias may have been the first in the Carpenter family to make pottery.

In addition to John Wesley, at least three more of Elias’s sons and a grandson made pottery. In 1860 Elias’s household included a twenty‑one-year-old “crocker” named Alexander Stamey (1821–1893). Potter John Alrand (b. 1834) lived next door.[9] All of this together supposes Elias’s involvement in the trade. Both Stamey and Alrand came to Lincoln County from neighboring Burke County, North Carolina, though little more is known about Alrand. Stamey’s brother, John (ca. 1798–1885), is referred to as “Potter Stamey” in a Clay County, North Carolina, estate-settlement document, suggesting that more than one family member made pottery.[10]

German-speaking neighbors surrounded the Carpenters. Almost everyone farmed, and some were also artisans who provided essential services and products to community residents. Potters were among the first to arrive in the region, among them Christopher Culp, John Dietz, David Hartzog, John Hefner, David Mauney, Henry Miller, John Pope, Peter Reese, Daniel (and perhaps his father, Adam) Seagle, Moses Seitz, Jacob Weaver, and Andrew Yount.[11]

Elias Carpenter married Sarah “Sally” Salina Johnson (1811–1880), whose brother, Amon Locke Johnson (1816–1893), was a potter, as were his sons, Harvey Make (1846–1931), Joseph Daniel (1848–1948), and Wade Dixon Cooper (1850–1931).

Amon Johnson’s nephew, Eli (1836–1917), the son of storekeeper Will-iam Burgin Johnson (1808–1866) and Elizabeth Carpenter (ca. 1804–after 1880), was a potter, too. William Burgin Johnson married Elias Carpenter’s sister, Elizabeth, in 1834.[12] While serving in the Confederate Army, Eli Johnson received a leg wound from a gunshot in 1864.[13] In 1870 Eli resided in Bandys Township, Catawba County, North Carolina. His cousins Joseph and Harvey Johnson lived with him and his wife, Mary (Martha A.) Lawrence Johnson. Each man was called a “mechanic,” describing his role as an artisan.[14] In 1880 Eli Johnson worked in the Jacobs Fork Township as a Catawba County potter.[15] Eli’s brother John Johnson says that Eli “moved his pottery to Virginia after the Civil War and there continued in the same work for many years.”[16] By 1900, Eli Johnson lived in the Pine Creek Magisterial District of Carroll County, Virginia, putting his residence to the northeast of, but not far from, his Carroll County Carpenter relatives.[17]

Amon Johnson operated a pottery shop in Lincoln County (later Catawba County) in an area called Jugtown.[18] He also served as Jugtown’s postmaster, as did his son, Wade D. C. Johnson.[19] During the Civil War, Amon served in Company C, 4th Regiment, North Carolina Senior Reserves. When he enlisted, in 1864, he was forty-seven years old.[20] After the war, his son Wade remained in North Carolina and made pottery alongside his father for the rest of his life (figs. 2, 3). Amon Johnson’s sons, Harvey Make (after whom John Wesley Carpenter named his first son) and Joseph Daniel Johnson, moved to South Carolina, married Lanford sisters there, and set up a pottery shop near Lanford Station in Laurens County.[21]

In 1840 Amon Johnson lived only a few households away from notable potters Daniel Seagle (ca. 1805–1867), David Hartzog (1808–1883), and Daniel Holly (1811–1899).[22] Holly was apprenticed to Seagle in 1828. As their contemporary, it stands to reason that he learned pottery-making from one of them or a potter associated with them. Perhaps Amon Johnson and Elias Carpenter were trained together, leading to Carpenter’s introduction to Johnson’s sister, Sarah Salina, whom he married in 1832.[23]

The Johnson family had close ties to the pottery-making Ritchie (Rüetschi) family. Wares made by Johnson and Carpenter potters are noted for traits similar to those seen on Ritchie-made pottery, so it is likely that training, or a working relationship, connected these families. Wade D. C. Johnson married Sarah Lavina Wyont Ritchie (1854–1915), the widow of potter Joseph Walter Ritchie (1854–1883).[24] Joseph’s father was potter Thomas Ritchie (1825–1909). Amon Johnson’s daughter, Sarah Ann (1843–1923), widow of Alfred A. Heavner (Havnaer; Havner), married Thomas Ritchie’s brother, Henry (b. 1822).[25] The Heavners’ sons, Royal Pinkney (1868–1929) and Harvey Hightower (1874–1961), made pottery in Catawba County.[26] They may have learned the trade from their stepfather, Henry, or another Ritchie potter. Susannah “Susan” Johnson (1850–1922), the daughter of William Burgin and Elizabeth Carpenter Johnson, and niece of Amon Johnson and Elias Carpenter, lived with and worked as a servant/housekeeper for Thomas Ritchie and, later, for his sons Robert and Luther Seth Ritchie.[27]

Thomas and Henry Ritchie were sons of potter Moses Ritchie (b. ca. 1793). Moses Ritchie’s first cousin, Paul Ritchie (b. 1810), also was a potter.[28] Born in Cabarrus County, North Carolina, Moses Ritchie may have been trained there by an earthenware potter before moving to Surry County (later Yadkin County), North Carolina, where he lived near Huntsville (est. 1792). Silas Vestal (b. 1799) operated a pottery shop there before moving to Greene County, Tennessee, and Ritchie may have worked there as a journeyman.[29] Three of Ritchie’s sons—Henry (b. 1822), Thomas (b. 1825), and Joseph (b. ca. 1829), all born in Surry County—made pottery. Moses Ritchie could have received his training through apprenticeship to one of several potters who worked in the vicinity of Cabarrus County, including Henry (Johann Heinrich) Wenzel (1734–1797), Benedict Mull (Moll) (1777–1857), or Thomas Pasinger (b. 1765), who was apprenticed under Moravian potter Henry (Johann Heinrich) Barroth (d. 1799) in Salisbury, Rowan County, North Carolina.[30] On the other hand, he could have learned the trade in the Catawba Valley from someone among the Seagle-Hartzog school of potters.[31]

Elias and Sarah Salina Johnson Carpenter had four daughters and six sons.[32] Their eldest son, William Franklin “Frank” Carpenter (1833–1873), called himself a carriage maker in 1860.[33] Alkaline-glazed stoneware marked “WFC” suggests that he was also a potter (fig. 4). John Johnson, whose brother was potter Eli Johnson, confirmed in a letter written in 1928 that “Franklin Carpenter was a potter until his death about 65 years ago.”[34]

Having more than one trade at the time was not unusual. Potters often called themselves farmers even when it was known that they made pottery; similarly, others who called themselves blacksmiths, teachers, or ministers also were known to practice the trade of potter. Decorative incised-line patterns added to WFC-marked pieces further connect Frank Carpenter to other family members’ pottery making and traits associated with Seagle, Hartzog, and especially Ritchie family potters.

Frank Carpenter’s leg was wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg on July 1, 1863.[35] During the war, he suffered numerous bouts of illness and spent much of the time in hospitals, at home on sick leave, and as a prisoner of war.[36] In 1870 he called himself a Lincoln County farmer.[37] Three years later, on April 10, 1873, he died from an unknown cause. By then, three of his brothers were living in Carroll County, Virginia, where they made pottery. In 1880 his widow, Mary Hoffman Carpenter, resided near Lincoln County potters James F. Seagle (1829–1892), son of Daniel, and John Goodman (1822–1907), who married Daniel Seagle’s daughter, Barbara.[38] Goodman’s brothers, Michael (b. 1824) and Jacob Tobias (b. 1828), from Cabarrus County (like Moses Ritchie), were potters. In 1850 Michael Goodman’s neighbor was potter Alexander Hill (b. ca. 1813), a Surry County native and an acquaintance of Moses Ritchie.[39] According to family historian Robert C. Carpenter, “The family of William Franklin Carpenter tell (sic) the story that all of his relatives left Lincoln Co. They returned once and found his widow Mary E. and family in severe poverty. They left some items for the family.”[40] Edith Carpenter Riggins (1931–2021) claimed that family members moved from Lincoln County to Carroll County, Virginia, due to an overabundance of potters and -impoverishment.[41]

The second son of Elias and Sarah Salina Carpenter, Jacob Carpenter (1837–1862), called himself a blacksmith when enlisting to serve the Confederacy on August 8, 1861. Six months later, on February 13, 1862, he died at home while on furlough due to an unidentified sickness.[42] Given that three of his brothers, and perhaps his father, Elias, made pottery, it is likely that he was trained as a potter, too.

Days after Jacob’s death, on February 22, 1862, Private John C. Speagle (b. ca. 1839), who married Elias and Sarah Salina Carpenter’s daughter, Martha M. Carpenter (1840–1918), died from acute meningitis at Camp Fisher, Virginia.[43] In 1870 his widow and his son Andrew Franklin “Frank” Speagle (b. ca. 1858) lived with Elias and Sally Carpenter.[44] Frank Speagle may have worked as a potter with Wythe County, Virginia, potter Ephraim Buck around 1880 when he lived about three houses away.[45] Following his first wife’s death, Frank Speagle married Carroll County, Virginia, native Malinda Jones on December 14, 1880.[46]

Elias’s son, Michael “Mike” Rufus Carpenter (1844–1917), was wounded in Virginia on October 14, 1863, at the Battle of Bristoe Station. He received a Minié ball shot to his left leg, just below his knee, injuring his tibia. Afterward, as his recovery allowed, he worked as an ambulance driver and drove a cooking utensil wagon as a regimental teamster. Captured by Union forces near Petersburg on March 27, 1865, he was released after the war on June 26, 1865.[47] His disability troubled him for the remainder of his life, though he farmed and worked in John Wesley Carpenter’s Pipers Gap, Virginia, pottery shop to the best of his ability. On September 1, 1917, Mike Carpenter died from injuries received from a fall, no doubt related to failing strength in his leg. His spinal cord was broken, causing complete paralysis of his lower body.[48]

When Elias’s son Adolphus Lafayette Carpenter (1846–1933) enlisted with the Confederacy at age seventeen, he united with Company B, 8th Battalion, North Carolina Junior Reserves. As with so many others, dysentery (attributed to colitis) placed him in a military hospital and furloughed him for home recovery.[49] Though he called himself a farmer when he enlisted, in 1870 and 1880 he told the Carroll County, Virginia’s census taker that he was a potter.[50] By 1880 Elias, Sarah Salina, and their daughter, Barbara, resided in Carroll County, next to Adolphus and his wife, Mary Lingafelt (Lingerfelt) Carpenter.[51] Around 1884, Adolphus moved his family to Sni-A-Bar township, Jackson County, Missouri, where he lived for the remainder of his life. It is not known if he made pottery there.[52]

According to granddaughter Edith Carpenter Riggins, one of John Wesley Carpenter’s legs was shorter than the other, likely preventing his enlistment as an infantry soldier during the Civil War.[53] A pension application filed by his wife, Emily, suggests that he enrolled in Company E, 9th Regiment, North Carolina Reserves.[54] Records for this unit are scarce, and the range of his military activity is unclear.

Following the war, when John Wesley Carpenter, still a single man, departed from Lincoln County to make a new start in Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, he and his brothers, Adolphus and Michael, carried with them the memories of war, sickness, death, and disruption of a promising future. Their grief was compounded when, not long after the war’s end, their brother Frank died, too.

The Carpenters’ woeful memories surely extended to the Johnson family. According to potter Harvey Make Johnson’s daughter, “Papa was a poor little foot soldier who joined the 11th North Carolina Regiment, in the Confederate Army, when he was 16. He was captured in his first battle and not paroled until the war ended. We’d ask him about how the war was and he’d say, ‘Horrible. Horrible.’”[55]

John Wesley Carpenter, who was neither the eldest nor the youngest of his male siblings, took on the task of guiding his surviving family members beyond their postwar miseries toward a new, more hopeful future. His own war experience may not have been as traumatic as that of his brothers and brother-in-law, but the pain of their loss and suffering indeed weighed heavily upon the Carpenter family. Their move away from Lincoln County to Pipers Gap, Virginia, initiated their restoration of prewar dreams. The Carpenters did not go to Pipers Gap without a purpose or essential skills required for their success. They were potters before they arrived there, and pottery-making was their best hope for finding their way forward (fig. 5).

The Catawba Valley Wares

It has long been supposed that alkaline-glazed stoneware marked “JWC” and “JC” and attributed to John Wesley Carpenter was made in association with the J. W. Carpenter pottery, located in Wiles, Wilkes County, North Carolina (figs. 6, 7). However, that shop belonged to James Welborn Carpenter, not John Wesley Carpenter, and no evidence of their association has been found. An 1892 Wilkes County deed made out by J. W. and Elizabeth Carpenter to the State of North Carolina in order to secure a fine due from a convicted man named R. F. Baldwin, describes the thirty-five-acre tract as “where on we live and on which is located J. W. Carpenter’s jug factory.”[56] Additional documents identify this man as James Welborn Carpenter. Philip Carpenter (ca. 1835–1918), originally of Wake County, North Carolina, was Welborn Carpenter’s father. No record of kinship to John Wesley Carpenter has been discovered.[57]

With that long-held misunderstanding resolved, it is now believed that John Wesley Carpenter and his family members made alkaline-glazed stoneware in Lincoln County before moving to Virginia, with some of it marked “JWC” (for John Wesley Carpenter) and “WFC” (for William Franklin Carpenter).

Both of the alkaline-glazed jugs shown in figure 8 bear the initials “WFC” (see figure 4) and incised, combed lines of decoration. The “2” on each one indicates two-gallon capacity. Close examination reveals fine lines (reeding) encircling the spout neck of the jug on the left in the image. Based on Frank Carpenter’s age, these jugs were probably made between 1850 and 1862, or after the Civil War to the time of his death, from 1865 to 1873.

More examples signed “JWC” are known. In addition to its glass runs, the bulbous, two-handle jug shown in figure 9 shows a tapered, reeded spout neck made up of a series of finely cut lines and a band of incised-line decoration around its middle. The jug shown in figure 10 has a similar spout neck and simple parallel lines of incised decoration. Spout necks styled like these are also seen on jugs made in Thomas Ritchie’s shop, such as the one shown in figure 11. The jug signed “JWC” that is shown in figure 12 differs enough from the one shown in figure 10 to suggest that someone else working alongside John Wesley Carpenter made it. Lines of decoration surround the body of the pitcher shown in figure 13. The ovoid jar marked “JWC” in figure 14 is reminiscent of an unsigned alkaline-glazed example discovered in an abandoned chicken coop located at the home of John Wesley and Emily Carpenter in Piper’s Gap, Virginia (fig. 15).

Undoubtedly, the Carpenter potters and their Johnson kin are connected through training. For example, the jug shown in figure 2—signed “WJ” (for Wade Johnson), like the Frank and John Wesley Carpenter examples—displays a reeded spout neck, straight and wavy lines of incised decoration, and a glass run. Those stylistic traits have long been associated with early Catawba Valley stoneware makers Daniel Seagle and David Hartzog. Wares made by Ritchie family potters share the characteristics, as likely do those made by others who learned the trade from someone in the Seagle-Hartzog school of potters.

The striking Daniel Seagle jug shown in figure 16 has a reeded spout neck and glass runs streaming through its alkaline glaze. Though it lacks a reeded spout neck, a David Hartzog jug has a glass run (and another that may contain iron) and a band of incised-line decoration (figs. 17, 18). Within the decorative band, Hartzog inscribed his mark: DAVIDHARTZOGHISMAKE.

The first Carpenter potter (presumably Elias Carpenter) and Johnson potter (Amon Johnson) surely learned the trade from one of the Catawba Valley’s earliest stoneware makers. Given their age, those two men could have learned pottery-making ca. 1826–1837. If their sons did not learn the trade from them, then someone in the Ritchie family might have taught them. A prime candidate is Thomas Ritchie, son of potter Moses Ritchie. The decorative patterns seen on the “TR”-marked jug in figure 19 are similar to those found on numerous Carpenter-shop wares.

The pan shown in figure 20 and the ovoid jar shown in figure 21 are thought to have originated in Thomas Ritchie’s shop. Each exhibits incised-line decoration remarkably similar to that applied by the Carpenters and associated potters to Pipers Gap, Virginia, wares. Many Thomas Ritchie jugs marked “TR” have reeded spout necks, and Ritchie sometimes added glass runs to his alkaline-glazed wares.

Comparing their decorated wares further advances a Ritchie connection to the Carpenters, including some made by Thomas Ritchie’s son, Marcus, such as the bottle and jug shown in figures 22 and 23. Adolphus Carpenter and Marcus Ritchie were about the same age, and generationally, the sons of Thomas Ritchie, Elias Carpenter, and Amon Johnson were contemporaries. The similarity between the atypical jug spout seen on the Thomas Ritchie shop’s jug and the one seen on the Carpenter Pottery’s Pipers Gap jug (fig. 24) further suggests that one of the Carpenters was a trainee or worker at the Ritchie pottery.[58]

The Carpenters in Pipers Gap

Regardless of the miseries he and others endured during the Civil War, John Wesley Carpenter must have struck out from the Catawba Valley for Virginia with a sense of hope (fig. 25). He possessed the skills of a potter and farmer. An entrepreneurial spirit and dreams bolstered those skills for a better future for himself and his extended family.

The amount of Virginia land he eventually possessed suggests that he farmed, which probably included cultivating fruit trees for brandy production. A 1910 letter to him from The Great American Herb Company of Washington, D.C., shows that he, as their agent, sold the enterprise’s Indian Herbs products (figs. 26, 27). The company’s assistant manager made plain their expectations of Carpenter: “We want your undivided interest in the work this year, and we are sure if you will work to get your people interested in their physical condition and in INDIAN HERBS as the safest and simplest remedy for them, you will not want to do anything else and will not need to.”[59] The letter encouraged Carpenter to make a strong appeal to his prospective customers, that Indian Herbs was a remedy for numerous ailments: “Tell the sick people around you what we have told you, then make them understand that INDIAN HERBS is simple and harmless, but acts directly on the blood and liver, starting right and doing the work of rebuilding right from the foundation, so that the cure is sure and lasting when it is accomplished, and the patient can stay cured.”[60]

Unfortunately, according to one family member’s account, John Wesley Carpenter’s belief in herbal medicine may have contributed to his death. After the removal with a pocket knife of a splinter lodged beneath his thumbnail led to blood poisoning, he died while relying on herbal treatment to cure his sickness.[61]

John Wesley and his brothers made many gains in Virginia. About 1868, brothers Michael Rufus and Adolphus Lafayette Carpenter left Lincoln County and settled just above the North Carolina state line near Pipers Gap in Carroll County, Virginia.[62] According to family lore, the Carpenters chose their new home because suitable clay for making pottery was available there, and their post–Civil War Lincoln County community was overrun by potters, which made making a living at their trade difficult.[63]

Both brothers called themselves potters when the 1870 U.S. Census taker visited in August of that year.[64] Michael, not yet married to Jane Bedsaul, resided with his brother Adolphus’s family. Their brother, John Wesley Carpenter, lived in Carroll County before February 6, 1873, when he married Surphina Bedsaul.[65] His location when the 1870 census was made is not known. Since the ownership of the Pipers Gap pottery is most often associated with John Wesley (and most wares made there bear the initials JC or JWC), then it is possible that he arrived at about the same time as his brothers but was overlooked by the census taker. He called himself a potter when the next count was made, in 1880.[66] By then, the three Carpenter brothers had been joined in Pipers Gap by their parents, Elias and Sarah Salina, and their sister, Barbara. Elias’s family residence is listed between those of potters Adolphus Carpenter and George [Washington] Bedsaul (1857–1889). John Wesley and Michael Carpenter lived a few miles away.

A search of land records suggests that the Carpenters did not immediately purchase land after moving to Virginia. All Carroll County land acquisitions appear to have been made jointly in the names of John Wesley and Michael Rufus Carpenter. Between 1875 and 1892, they purchased at least 263 acres. In 1897 John Wesley paid Michael and his wife, Jane Carpenter, $250 for 166 acres. On that same date, John Wesley, Emily (his second wife), and Michael Carpenter conveyed 133 1/2 acres to Jane Carpenter for the sum of $250.[67]

The Carpenters may have been lured to Pipers Gap by Carroll County resident William R. Bedsaul. Since land deeds do not indicate that any one of the three brothers acquired property before 1875, some eight years after arriving in the county, it is possible that they first worked in partnership with him. Perhaps they were tenants on his land until they had enough capital of their own to purchase property and to take charge of their business affairs independently. F. Clyde Bedsaul (1900–1987) says that his grandfather, William R. Bedsaul, and John Wesley Carpenter were partners, lending credence to this idea.[68]

Adolphus Carpenter may have set up a pottery in the Coal Creek section of Carroll County apart from the one operated by his brothers, John and Michael. His brother-in-law, potter George W. Bedsaul, lived nearby. On the other hand, Bedsaul may have run a shop there.[69] Neighbor David Campbell (ca. 1854–1925), whose father was potter William Campbell (ca. 1814–1899) of Lincoln and Catawba Counties, North Carolina, purchased land from Adolphus Carpenter near the time when Adolphus’s family (and George W. Bedsaul) moved to Missouri.[70] After leaving North Carolina, William Campbell worked as a potter in Wythe and Smyth counties, Virginia.[71] In 1880 David Campbell’s Pipers Gap household included his brother, potter William Dess Campbell (ca. 1852–1912). Two more of David Campbell’s brothers, Lindsey (ca. 1849–1883) and Hosea (ca. 1855–after 1920), were potters in Tennessee and southwest Virginia, so David Campbell might have been a potter, too.[72] Lindsey Campbell’s pottery in Johnson County, Tennessee, produced alkaline-glazed stoneware in a groundhog-styled kiln measuring about 19 feet by 11.7 feet, comparable in size to those used by North Carolina’s Catawba Valley potters.[73]

In 1880, potter Charles Cole (1827–1929) and his son, Wiley Cole (1857–1930), lived and worked in Pipers Gap township.[74] Born in Grayson County to Hawk Cole, Charles Cole moved to Carroll County between 1866 and 1868. In 1870 he called himself a saddler, and in 1900 he was a harness maker. Wiley Cole worked as a farm laborer in 1870. Perhaps the Coles set up a pottery to compete with the Carpenters. However, it seems more likely that they worked with the Carpenters after being trained by them.[75]

Michael Carpenter’s son, James Emmett Carpenter (1872–1964), supplied substantial evidence about John Wesley Carpenter’s pottery shop in Pipers Gap when he was interviewed in 1959 by F. Clyde Bedsaul. Additional information came from other longtime Carroll County residents. As stated above, Bedsaul claimed that his grandfather William R. Bedsaul (1833–1909) and John Wesley Carpenter were business partners. Bedsaul recounts that “Three Carpenter brothers, John C. [W.], Mike and Adolphus, accompanied by William R. Bedsaul, went to Lincolnton, N.C., to learn the pottery trade.”[76]

In fact, the opposite is true. The Carpenters came to Virginia from Lincoln County fully prepared for pottery making. William R. Bedsaul’s involvement in the trade is less certain. As a prominent farmer and justice of the peace, Bedsaul might have traveled to Lincoln County to recruit the Carpenters to come to Pipers Gap. Bedsaul’s son, George, may have gone to the Catawba Valley as a potter’s apprentice (perhaps for Thomas Ritchie), leading to his and his father’s acquaintance with the Carpenters. Thereafter they might have been enticed to relocate to Pipers Gap to set up a pottery shop with the elder Bedsaul as a partner.

Undoubtedly, the Carpenter-Bedsaul relationship was strong. William R. Bedsaul’s daughter, Surphina Jane (1854–1880), was the first wife of John Wesley Carpenter and the mother of their two children, Mollie (1873–1894) and Harvey Make Carpenter (1877–1960). Bedsaul’s son, George Washington Bedsaul, was a potter who undoubtedly worked with his Carpenter brothers-in-law. He married Sarah Elizabeth Carpenter (1853–1933), the daughter of Elias and Sarah Salina Johnson Carpenter.[77] Michael Carpenter married Jane Bedsaul. A jar bearing the name G. W. Bedsaul, with incised decoration like that applied to many Carpenter-made wares, has been identified (fig. 28). In 1881 George W. and Sarah E. Bedsaul purchased from Martin and Jane Hanks 15 1/2 acres lying adjacent to the lands of Adolphus Carpenter. On July 7, 1883, the deed was delivered to William R. Bedsaul for the grantee.[78] Like Adolphus Carpenter, George W. Bedsaul moved from Carroll County to Missouri sometime around 1884. Family accounts say that he died in Oak Grove, Missouri, on July 17, 1889. In 1910 his widow, Sarah E. Carpenter Bedsaul, was in Oak Grove, near Adolphus and Mary Carpenter.

The Clay

In 1959 Emmett Carpenter recalled as a boy hauling ox-driven wagonloads of white clay to the John Wesley Carpenter pottery. The shop’s clay was dug at two sites, and it took half a day to transport it about five miles on winding, unpaved roads. Some of it came from Philip Kinzer’s bottomland near Wolf Glade, and the rest came from Tom Jones’s farm at Woodlawn.[79] His mention of white clay is significant because most of the Carpenters’ salt-glazed ware was slip-coated with white clay before being placed in the kiln. This unique trait makes the shop’s pottery immediately recognizable, with or without the presence of John Wesley Carpenter’s abundant “JC” and capacity marks. A Virginia geological survey suggests that pink feldspar, weathered from arkosic beds (sandstone > 25% feldspar), was the white kaolin’s source.[80]

The same survey says that the persistence of limonite in the area’s residual clay “indicates that these hydrous iron oxides were derived from the solution of disseminated iron-bearing minerals in the rocks . . . during weathering” and were subsequently “concentrated by deposition in the residual clays.”[81] If the clay found by the Carpenters was like this, then its iron content might have generated an undesirably dark salt-glazed body. Some (perhaps early) examples of their Carroll County output, like those shown in figures 29 and 30, are dark-colored, causing them occasionally to be confused with Wilkes County, North Carolina, wares, which likewise were created using clay high in iron content. The Carpenters’ problem was resolved when the choice was made to coat each piece of pottery with a kaolin-derived slip before salt-glazing. As a near twin to the jug shown in figure 30, the alkaline-glazed example shown in figure 31 exhibits the contrast between the Carpenters’ salt and alkaline-glaze treatments.

Emmett Carpenter described how the clay was processed and prepared for kiln-firing. Bedsaul relays what Carpenter told him about it:

The “mud mill” was crude and consisted of a vertical beam of wood, armed with four or five metal knives, which turned in a square box. This upright shaft was pegged to a sweep and rotated slowly when pulled by a plodding farm horse. It operated much like the old-fashioned cane mill. Raw clay was cut and mixed as water was added to form the desired consistency. It took three or four hours to finish this first process. Then the prepared clay was dipped out of the box with bare hands, shaped into large balls, stored in pits and covered with wet cloths.[82]

Once formed into jugs, crocks, and other shapes, unfired vessels were set aside to dry on shelves in a shed where they sat for four or five days. Then, an unusual step was added to the process: “They were returned to the wheel where a thin layer of very white clay solution was ‘glazed’ or rubbed on. After two more days of drying they were carefully carried into the furnace.”[83]

Sometimes potters substituted Albany slip or Bristol glaze for alkaline glaze or salt glaze. What makes the Carpenters’ Virginia pottery unusual, perhaps unique, is the addition of a white kaolin slip before salt-glazing.

Turning the Clay

Emmett Carpenter describes how the shop’s wheel that was used to turn clay was like those typically found in traditional North Carolina potteries.[84] Each one’s heavy flywheel was pushed into a turning motion by way of a foot-powered treadle. Bedsaul, in his account, refers to the treadle as a foot pedal.[85] A ball of clay, placed on a twelve-inch lathe head connected to the flywheel by a vertical iron crankshaft, was transformed into a useful vessel when the turner’s wetted hands brought out its profile from the shapeless lump of clay. Once satisfied with the shape, the potter used a wire pulled between his two hands to cut away the still-pliable jug, churn, crock, pitcher, or chamber pot from the lathe head.

Many of the region’s potters stood on one leg at the wheel while pushing the treadle with the other. The potter’s wheel described by Bedsaul from Emmett Carpenter’s memory allowed the turner to sit astride a saddle-like seat while working. A photograph taken circa 1931 shows Lincoln County–born potter Albert Fulbright (1867–1950) straddling a treadle wheel’s plank seat, confirming its use in western North Carolina (fig. 32).[86] The saddle-like arrangement may have been helpful in the Carpenter shop, given Michael Carpenter’s battle-derived disability that at times required him to use crutches while standing and John Wesley Carpenter’s reported uneven leg length.

The Kiln

The Carpenters’ Pipers Gap pottery kiln, once used to fire salt-glazed stoneware and some alkaline-glazed ware, was dismantled around 1912.[87] The large soapstone blocks that had been employed when constructing the kiln’s walls were used to build a chimney for a house constructed by John Wesley Carpenter for himself and his wife, Emily (fig. 33). The chimney was damaged in 1989 by winds from the tropical remnant of Hurricane Hugo, and subsequently was taken down. The soapstone blocks were piled nearby, where they are preserved (fig. 34).

The kiln’s hand-cut soapstone blocks were quarried about a mile from the pottery shop, near Hanks Knob. From the arch of a geologic fold near Hanks Knob, hornblende gneiss passes southwesterly into a source of soapstone. The geologic survey referenced earlier states that soapstone found in the area tends to be “pale-greenish gray, saws readily, and breaks into slabs along the schistosity.” Much of it is heavily pitted, and some holes are filled with limonite.[88] The Carpenter pottery’s soapstone kiln blocks are likewise heavily pitted (fig. 35).

In the spring of 2014, John Wesley Carpenter’s granddaughter, Edith Carpenter Riggins, revealed the kiln’s location to Marc King. King’s research identified John Wesley Carpenter as the potter long known to collectors who frequently marked his pots with the letters JC—a fact confirmed by Edith Riggins. He described the site as overgrown with a few scattered rocks remaining from the kiln’s prior construction. A portion of the kiln extended into the base of a hill that was bordered by two small spring-fed streams. In 2016, archaeologist January Costa, along with others representing North Carolina’s Lincoln County Historical Association, visited the site where she photographed its remains and measured its dimensions (fig. 36).

Bedsaul’s retelling of Carpenter’s memories of the site provides an illustrative description of the kiln and its use:

The furnace and all equipment was home-made—built by their own hands. Soapstone blocks were cut in a quarry on the Creed Hanks Knob and hauled for nearly a mile.

The furnace was an arched structure extending 24 feet into a hillside, 13 feet wide and about five high. Three doorways or flues, 27 inches wide and three or four feet high, were equally spaced across the front.

A broad chimney of home-burned bricks extended eight feet above the back end. The floor had two levels. A fire pit of about one-fourth the length was first. The remaining space, extending on back to the chimney, was two feet higher. Crocks were burned upon this upper level. The soapstone arch over this area was pierced by numerous holes or small windows. These were stoppered with earthenware plugs which bore chines on their outer ends.

This made it possible to lift them out, hot, by use of forked sticks when it was time to pour glazing material upon the white-hot vessels below. Wooden catwalks extended across the furnace to protect the workers from the heated arch during the glazing operations. The whole furnace was sheltered by a board-covered shed.[89]

Anyone familiar with kilns utilized in North Carolina’s Catawba Valley region will recognize this kiln’s similarity to those used there in the production of alkaline-glazed stoneware. These kilns have long been compared to German Cassel kilns, exhibiting similar design and functionality. Daniel Seagle was one of the Catawba Valley’s earliest potters. His kiln, excavated by Linda Carnes-McNaughton in 1987, was remarkably similar in size (23' by 10') to the Carpenter kiln (24' by 13'). Two more Catawba Valley kilns, built by brothers Enoch and Harvey Reinhardt, are nearly identical, each measuring approximately 24' 11" by 11' 6". Both Reinhardt kilns had three fireports, like the ones described by Emmett Carpenter, spaced out across their front walls and opening into a fire pit.[90]

Cassel kilns typically had an interior bag (flash) wall to separate the fire pit from the setting floor, where wares were arranged for firing. However, Catawba Valley kilns used for alkaline glazing appear to lack this feature. The purpose of a bag wall is to prevent wares from being directly impacted by wood thrown into the fire pit or by stirred-up wood ashes. Since Emmett Carpenter’s kiln description fails to mention a bag wall, perhaps his memory was faulty or the Carpenter kiln lacked that component. Also, Catawba Valley potters loaded and unloaded their kilns through an opening at the base of the furnace’s chimney, and even though Emmett Carpenter might not have mentioned this fact, the kiln’s overall design suggests it was true there.

The addition of ports with removable earthenware plugs in the Carpenter kiln’s arch is the most significant modification to an otherwise typical Catawba Valley–styled furnace. Further, they burned dry chestnut wood, not pine; it was, according to Charles G. Zug III, “the only wood used in the Catawba Valley.”[91] These openings made glazing the pots possible by pouring salt into the kiln while the wares were white-hot.[92] Emmett Carpenter told Clyde Bedsaul that workers crossed over the arch on wooden catwalks to disperse seventy-five pounds of salt into the kiln. Afterward, heavy sheets of metal sealed off the kiln’s three openings. Over two days, the wares inside cooled enough to be removed.

So, except for the addition of salting ports, the Carpenter kiln was like the North Carolina alkaline-glazing stoneware kilns used in the Catawba Valley region, primarily by potters of German descent. In both cases, the type is fundamentally a modified Cassel kiln.

Unlike the Catawba Valley kilns, the ones used by North Carolina’s salt-glazed stoneware production in the state’s eastern Piedmont Region were smaller in size, typically had one opening leading to the firebox, were loaded and unloaded through this opening rather than through the chimney, and had a taller, narrower chimney.

The Carpenters’ use of a Catawba Valley–styled kiln, primarily used by them for creating salt-glazed stoneware, might be a unique adaptation among Southern potters and potteries. It is unknown why they decided to produce salt-glazed stoneware in Virginia instead of the alkaline-glazed ware they had made in North Carolina. The choice of a kiln like theirs to make salt-glazed stoneware suggests that it was an idea of their own, not one taught them by a salt-glazer. Had that been the case, they might have been persuaded to use another, smaller, kiln design altogether. In any event, the Carpenters could well be the only Southern potters successfully to produce alkaline-glazed and salt-glazed stoneware at the same site—perhaps in the same kiln.

The Pipers Gap Wares

The Carpenters undoubtedly were skilled at alkaline-glazed stoneware production, so one must wonder what led them to switch to salt-glazed stoneware after moving to Virginia. When they arrived in Carroll County, potters to their northeast in Richmond, Petersburg, and Alexandria made significant quantities of cobalt-decorated salt-glazed stoneware. Increasingly, in the state’s Shenandoah Valley potteries, especially in Shenandoah and Rockingham counties, earthenware was being supplanted by salt-glazed stoneware. According to H. E. Comstock, beginning around 1870 through the end of the century, seventy-five percent of the total production of Shenandoah Valley ceramics consisted of stoneware. The demand for salt-glazed stoneware, in some instances, called for the construction of new kilns for this purpose.[93] Perhaps the Carpenters learned early on in their Pipers Gap venture that Virginia buyers preferred the appearance of salt-glazed over alkaline-glazed pottery and thus adapted their operation to accommodate the market’s demands.

Salt was in short supply during the Civil War, but after it there was an increasingly plentiful supply. In Virginia’s Smyth and Washington counties, the Saltville Salt Works, located not far from Carroll County, could have amply supplied the Carpenters’ needs for glazing with salt. The Carpenter kiln, groundhog in design, probably performed well from the beginning when so utilized. Salt vapors, which wreak havoc on kilns’ brick walls and arches over time, were not likely problematic since the kilns’ burning chamber walls were made of soapstone.

Salt-glazing is a more straightforward yet no less challenging process than alkaline-glazing. Alkaline glazing requires a mixture of finely ground glass (or another source of silica), some clay for binding, water, and a flux (typically wood ashes). Once formulated, this glaze was placed on ware surfaces before kiln-firing, requiring considerable labor. With salt glaze, no such “glaze” is needed. Instead, unglazed pots, when exposed to the gaseous vapors created when common salt is introduced into a kiln at very high temperature, “leak” out native silica from their clay, creating a glassy, often “orange peel” textured surface.

At first, John Wesley and his brothers may have pursued the simplest form of salt-glazing, as previously described, without the addition of kaolin slip. The glazing on these examples seems adequate, but the dark clay color, when burned, might not have been deemed satisfactory by John Carpenter or his earliest buyers. Perhaps the region’s iron- and manganese-stained clays prevented the creation of lighter-colored wares. The Carpenters’ solution—one that added back work not typically required when salt glazing—was to coat each pot with a kaolin-based slip before salt glazing. Apparently it was John Carpenter’s good fortune to discover a white clay that sufficiently adhered to and matched the shrinkage of his pots’ underlying clay without diminishing the desired effect of salt glazing.

Sometimes, earthenware potters covered red or dark-burning clays with a lighter-colored engobe to create a brighter surface to which slip-trailed decoration could be added. The overall surface was then coated with a clear lead glaze. Applying a similar two-step process for stoneware production, like that achieved by the Carpenters, is rare, perhaps unique, among Southern potters. The examples shown in figures 37–41 exhibit the Carpenter pottery’s distinctive light- to medium-gray color achieved by the slip-coating and salt-glazing process described above.

John Wesley Carpenter never abandoned the skills for making alkaline-

glazed stoneware that he learned as a Catawba Valley potter. F. Clyde Bedsaul, drawing on his conversation with Emmett Carpenter in 1959, makes that clear when describing the shop’s method for grinding glass for glazing:

Another odd piece of equipment was a mill for grinding glass. It consisted of one stationary “mill rock” and a smaller, revolving one on top. One edge of this upper stone was supported by a small wooden beam, swinging from a tripod. This eccentric connection made it possible for a man to turn it by hand.

The “walloping” and sliding of one rock upon another ground the -broken glass into powder which was used instead of salt for glazing special wares.[94]

Some alkaline-glazed wares marked with capacity numbers and the initials JC are known. They seem to represent John Wesley Carpenter’s “special wares” made the Catawba Valley way. The example shown in figure 42, marked “JC 2” (for two gallons) and coated with a brown-green alkaline glaze, bears a wavy band of incised, combed decoration like that observed on many of the pottery’s salt-glazed pots. The one-gallon storage jar illustrated in figure 43 is marked “JC 1” (one gallon).

Though unsigned, the alkaline-glazed jar in figure 44, twice dated 1884 on its rim, is attributed to the Pipers Gap pottery. Its sloping, angled rim is similar to that on the signed G. W. Bedsaul jar in figure 28. The significance of the year is unclear, although it might be when both Adolphus Carpenter and George Bedsaul departed Pipers Gap for Missouri.

The outstanding alkaline-glazed example in figure 45 is not signed, but its form, glaze, and decoration (including glass runs) strongly suggest its association with the Carpenter pottery. It displays both of the commonly applied decorations used there, for example combed bands of horizontal and wavy lines. Although its expert creation suggests a John Wesley Carpenter product, its rim is similar to one on the jar in figure 28 signed “G. W. BEDSAUL” and the large crock in figure 44 dated 1884. Its decorative lines, as executed, resemble the ones applied to the signed Bedsaul jar. If it is Bedsaul’s work, he learned the trade well and created a masterpiece pot.

The most unusual of the Carpenters’ creations are examples like those in figures 47 and 48. Other similarly decorated specimens are known, including pitchers, a lidded jar, and a mug dated 1881. The jug (see fig. 47) bears John Wesley Carpenter’s initials, J.W.C., the date 1881, a series of crosses, a pine tree, and the figure of a man; the pitcher (see fig. 48) is signed “E. M. Carpenter.” Members of the Carpenter family possess both vessels. John Wesley Carpenter married Emily Hanks on December 16, 1880. Although some records have her name as Emily Amanda, U.S. Census records have her listed as Emily M. Carpenter on more than one occasion. The pitcher has two kinds of crosses, a pine tree and a symbol shaped like a whirligig.

Another similarly decorated pitcher, associated with the Bedsaul family in Missouri, is known (fig. 49). It includes a whirligig, a cross, and pine tree motifs. A note found inside the pitcher when it was purchased, written by Frances E. Bedsaul in 1984, states that her grandfather, Peter Bedsaul (1845–1932) of Missouri, acquired the pitcher in Carroll County, Virginia, while visiting family members there.[95]

Cobalt smalt on Carpenter wares has not otherwise been observed, except when applying stenciled numerals and the initials J.C. and J.W.C. on some presumably late wares (fig. 50). Carpenter sometimes combined his more typical stamped “JC” mark and capacity marks with stenciled versions (fig. 51). For example, his cobalt stenciled application is found on the remnant of a prototype headstone made by John Wesley Carpenter and bearing his initials (fig. 52). According to family members, this later venture failed because the thick slabs were prone to cracking due to insufficient drying.

Decoration

Many of the Carpenter shop’s jugs, crocks, pitchers, and other forms are decorated with incised, combed bands of parallel lines. Some bands encompass a series of thin, horizontal lines; some, using the same multi-line combing technique, are made up of undulating waves of lines (fig. 53). Other potters used similar motifs. The Fox family, potters of German descent who resided in Chatham County, North Carolina, made salt-glazed stoneware and sometimes executed similar decorations, including combed bands of horizontal and wavy lines. Lincoln (now Catawba) County earthen-ware potter, Jacob Weaver (1774–ca. 1846), slip-trailed similar bands of straight and wavy lines inside earthenware bowls and pans. Early Catawba Valley stoneware potters, like David Hartzog, Daniel Seagle, and members of the Ritchie family, all of Germanic descent like the Foxes and Weaver, often included incised line decoration when turning out their pots. A grandson of David Hartzog, Poley Carp Hartsoe (1876–1960), applied similar incised decorations to his ware well into the twentieth century (fig. 54). As noted earlier, wares attributed to William Franklin Carpenter, John Wesley Carpenter, and Johnson family potters that were associated with them are decorated in this manner. From this tradition, the Carpenters most likely derived their style using a combing implement, perhaps the same type used by John Wesley Carpenter when tooling finely reeded necks on his Catawba Valley–made jug spouts.

A technique less used by the Carpenters in Carroll County than in Lincoln County is the addition of glass fragments to rims, handles, and spouts, which creates attractive drips and runs through vessels’ primary glaze. Glass runs show up plainly against alkaline glaze, as is evident when applied to the jar illustrated in figure 9. If added to the Carpenters’ kaolin slip-coated and salt-glazed surfaces, they would be less dramatic in appearance, which could explain the apparent absence of glass runs used by them in Virginia (figs. 55, 56).

Conclusion

Charles G. Zug III, folklorist and author of Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina, lists a single Carpenter potter in his index of North Carolina potters—Franklin Carpenter of Lincoln County—but says nothing more about him. Howard A. Smith’s Index of Southern Potters has no potter named Carpenter. Christopher England’s England’s Quick Reference to North Carolina Makers includes J. W. Carpenter of Wiles, North Carolina, who, as explained above, is unrelated to Lincoln County’s Carpenter potters. The MESDA Craftsman Database, maintained by the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (Winston-Salem, N.C.), does not refer to potters named Carpenter.

As this article has demonstrated, however, Franklin Carpenter’s brothers John Wesley, Michael Rufus, and Adolphus made pottery, as did their nephew, Andrew F. Speagle. Their father, Elias, might have been a potter. Their pottery-making connects them to numerous potters, among them Bedsaul, Campbell, Cole, Johnson, Ritchie, Stamey, and perhaps other turners, including the Goodmans, Hartzogs, and Seagles. Pottery-making may have been the key to their adaptation to life in the post–Civil War South.

Building on the value of their craft, John Wesley Carpenter appears to be the one who led his family to make some life-altering decisions. The Carpenters first worked in North Carolina but left behind generations of family and community ties when they moved to Pipers Gap, Virginia, seeking freedom from impoverishment. There they produced both alkaline-glazed and salt-glazed stoneware, a fact setting them apart from other Southern potters. A thin slip of kaolin added to their turned wares’ surfaces before salt glazing made their work unique. Their Virginia wares’ decorative motifs unquestionably tied them to their makers’ Catawba Valley, North Carolina, heritage, making it both functional and, at times, quite beautiful. Those were purposeful choices.

While a potter might acknowledge the artistry of his work, Zug’s seminal work describing the history of North Carolina’s folk potters makes clear that a traditional potter’s craft was principally a business to him. As Zug put it, “In purely human terms, the folk pottery provided the extra income that could raise the quality of life for an ambitious man and his family.”[96] Both aspects of his trade were familiar to John Wesley Carpenter. Moreover, he sensed how his family’s emergence from personal tragedy and a war-ravaged Southern economy depended on their ability to produce pottery in a new way for a new market. Consequently, he charted a course as potter, farmer, brandy maker, and herbal remedy salesman, but mostly as a family leader. Although no one in the Carpenter family makes pottery today, his legacy as an artisan persists through his great-grandson and namesake, John Wesley Carpenter, who is a Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, schoolteacher, songwriter, and woodworker, a talent befitting the Carpenter family name.

I appreciate the assistance of Carpenter family members John Wesley Carpenter, Edith Carpenter Riggins, Robert Riggins, Ken Riggins, Cindy Quesenberry Akers, and Kathy Showalter Dalton.

Robert W. Ramsey, Carolina Cradle: Settlement of the Northwest Carolina Frontier, 1747–1762 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1964), p. 150.

Mark Smith, Lifting High the Cross for 200 Years: St. John’s Lutheran Church (Baltimore, Md.: Gateway Press, 1998), p. 26.

In his book Carpenters A Plenty ([1982; reprint, Baltimore, Md.: Gateway Press, 1993], pp. 1–14), Robert C. Carpenter makes a strong case for this assertion. One source claims that Hans Zimmerman, upon his arrival in North Carolina, was the high priest for a religious group referred to as New Lights or New Mooners. See Smith, Lifting High the Cross for 200 Years, p. 26.

William L. Sherrill, The Annals of Lincoln County North Carolina (1937; reprint, Baltimore, Md.: Regional, 1967), p. 21.

Ibid., p. 36.

Carpenter, Carpenters A Plenty, p. 33.

Ibid., p. 36.

U.S. Federal Census, 1860, Lincoln County, North Carolina.

“Potter Stamey” (John Stamey), Clay County, North Carolina, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1665–1998.

The names of some of these potters were first brought to the author’s attention by Scott W. Smith in an article titled “Documenting Early Catawba Valley ‘Potters,’” in Traditions in Clay, no. 13 (Raleigh: North Carolina Pottery Collectors’ Guild, 2006), pp. 2–7, and a chapter by the same author titled “The Earliest Catawba Valley Potters,” in Valley Ablaze: Pottery Tradition in the Catawba Valley (Conover, N.C.: Lincoln County Historical Association, 2012), pp. 1–4.

Carpenter, Carpenters A Plenty, p. 38.

“Eli Johnson,” ancestry.com, U.S., Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861–1865.

U.S. Federal Census, 1870, Lincoln County, North Carolina.

U.S. Federal Census, 1880, Lincoln County, North Carolina.

Sherrill, Annals of Lincoln County North Carolina, p. 444.

U.S. Federal Census, 1900, Carroll County, Virginia.

Bethia Caffery, “Mr. Johnson’s Daughters,” St. Petersburg (Fla.) Independent, February 24, 1976, p. 2-B.

“Amon L. Johnson,” appointment as Postmaster, Jugtown, Catawba County, North Carolina, August 6, 1875, ancestry.com. U.S. Appointments of U.S. Postmasters, 1832–1971.

“A. L. Johnson,” Confederate service record, www.fold3.com

Caffery, “Mr. Johnson’s Daughters,” p. 2-B.

U.S. Federal Census, 1840, Lincoln County, North Carolina.

Elias Carpenter and Sally S. Johnson, license for a marriage, Lincoln County, North Carolina, September 26, 1832, ancestry.com, North Carolina, U.S., Marriage Records, 1741–2011.

Wade D. C. Johnson and Sarah L. Ritchie, certificate of marriage, March 14, 1885, Catawba County, North Carolina, ancestry.com, North Carolina, U.S., Marriage Records, 1741–2011.

Henry Ritchie and Sarah Heavner, certificate of marriage, September 26, 1885, Catawba County, North Carolina, ancestry.com, North Carolina, U.S., Marriage Records, 1741–2011.

Charles G. Zug III, Turners and Burners: The Folk Potters of North Carolina (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986), p. 440.

U.S. Federal Census, 1880, Bandys Township, Catawba County, North Carolina; U.S. Federal Census, 1900, Jacobs Fork Township, Catawba County, North Carolina; U.S. Federal Census, 1920, Jacobs Fork Township, Catawba County, North Carolina. Susan Johnston (sic) is called a “lodger.” See also North Carolina Standard Certificate of Death for Susan Johnson, Jacobs Fork, Catawba County, North Carolina, filed March 20, 1922, where it is stated that she “Made home with L. S. Ritckey [sic].”

U.S. Federal Census, 1850, Lincoln County, North Carolina.

The 1820 U.S. Federal Census for Surry County, North Carolina, shows that four people in Silas Vestal’s household were “engaged in manufactures.” In the 1820s Silas Vestal moved to Greene County, Tennessee, and operated a pottery there. According to a Russell family historian, Greene County resident Benjamin Allen Russell was an apprentice to Silas Vestal around 1825 before working as a potter for Peter Harmon.

See Stephen C. Compton, “Research Note: The Eighteenth-Century Potters of Salisbury and Rowan County, North Carolina,” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts 39 (2018): 143–56.

The similarity of some Ritchie (and Johnson, Carpenter, and Bedsaul) wares to Seagle wares leaves open the possibility that Moses Ritchie learned the trade from Adam Seagle before passing along Seagle family traits to his sons, including Thomas Ritchie. After working in Huntsville, North Carolina, Moses Ritchie moved to the Catawba Valley, where he made pottery.

William Franklin, Mary A., Jacob, Martha M., John Wesley, Michael Rufus, Adolphus Lafayette, Christopher Sylvanus, Sarah Elizabeth, and Barbara Frances.

U.S. Federal Census, 1860, Lincoln County, North Carolina.

Sherrill, Annals of Lincoln County North Carolina, p. 445.

John W Busey and Travis W. Busey, “William Frank Carpenter,” Confederate Casualties at Gettysburg: A Comprehensive Record, vol. 2 (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2017), p. 892.

“William Frank Carpenter,” Confederate service record, www.fold3.com.

U.S. Federal Census, 1870, Lincoln County, North Carolina.

U.S. Federal Census, 1880, Lincoln County, North Carolina.

Brothers John, Michael, and Jacob Tobias Goodman were sons of Daniel and Margaret Kluttz Goodman of Cabarrus County, North Carolina. Michael and Tobias are first identified as potters in the 1850 U.S. Federal Census.

Carpenter, Carpenters A Plenty, p. 52.

Marc King, “Mysterious JC, Potter, Identified,” Voices 20 (2016): 2.

“Jacob Carpenter,” Confederate service record, www.fold3.com.

“Jno Speagle,” Confederate service record, www.fold3.com.

U.S. Federal Census, 1870, Lincoln County, North Carolina.

U.S. Federal Census, 1880, Wythe County, Virginia; J. Roderick Moore, Index of Great Road Potters, “Earthenware Potters Along the Great Road in Virginia and Tennessee” (Ferrum, Va.: Blue Ridge Institute and Museum, 1983).

“A. F. Speagle and Melinda J. Jones,” marriage certificate, Surry County, North Caro-lina, December 14, 1880. North Carolina, U.S., Marriage Records, 1741–2011.

“Michael Carpenter,” Confederate service record, www.fold3.com.

“Michael Rufus Carpenter,” certificate of death, September 1, 1917, Carroll County, Virginia, U.S., Death Records, 1912–2014.

“Adolphus Carpenter,” Confederate service record, www.fold3.com.