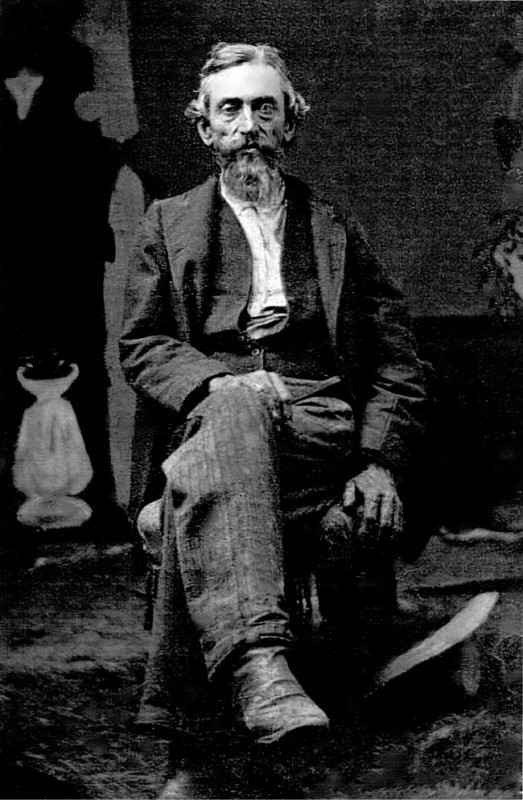

Photograph of John Wesley Carpenter (1842–1913), ca. 1880–1885. (Courtesy of the Carpenter family.)

Jug, attributed to Wade D. C. Johnson (1850–1931), Catawba County, North Carolina, ca. 1880–1900. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 13 1/4". Mark: incised “W J” four times. (Courtesy, Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society.)

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 2.

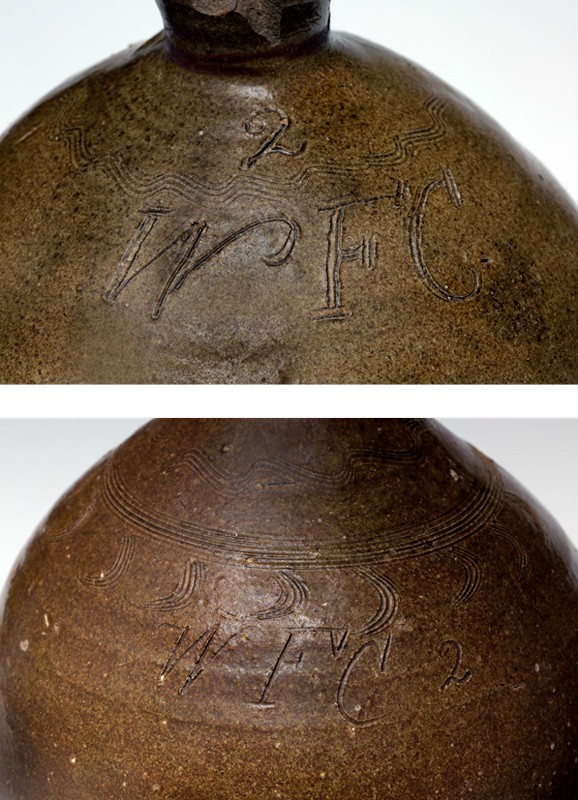

Details of the jugs illustrated in fig. 8, both inscribed “WFC” and “2”.

Genealogical chart showing the interrelationship between several pottery-making families, among them Carpenters, Johnsons, and Ritchies.

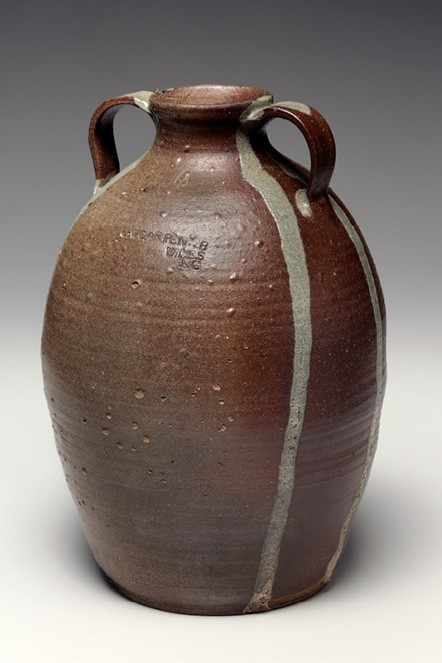

Six-gallon jug, J. W. Carpenter Pottery, Wiles, Wilkes County, North Carolina, ca. 1890. Salt-glazed stoneware with glass runs. H. 17 3/8". Mark: “J.W. CARPEN[TE]R / WILES / NC” (Courtesy, Wilkes Heritage Museum, Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) Long presumed to be associated with John Wesley Carpenter, this late-nineteenth-century pottery shop was owned and operated by James Welborn Carpenter. No family relationship between the two potters is known.

Six-gallon jar with four lug handles, attributed to J. W. Carpenter Pottery, Wiles, Wilkes County, North Carolina, ca. 1890. Salt-glazed stoneware with glass runs. H. 16 1/2". Mark: “6” (William C. and Susan S. Mariner Collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Two-gallon jugs, attributed to William Franklin Carpenter, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1873. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. Left: H. 13".

Marks: incised “WFC” and “2” (Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society Collection.) Right: H. 12 1/2". Marks: incised “WFC” and “2” (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Five-gallon jug, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with glass runs. H. 16 1/2". Mark: incised “JWC 5” (Courtesy, Wilkes Heritage Museum, Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) Opposite the signature are inscribed additional indecipherable letters/numerals. This jug, and other wares signed “JWC” in script, were probably made by Carpenter in Lincoln County, North Carolina, prior to his relocation to Pipers Gap, Virginia.

Two-gallon jug, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/2". Mark: incised “JWC 2” (Courtesy, Wilkes Heritage Museum, Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Half-gallon jug, Thomas Ritchie Pottery, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, second half of the nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". Mark: “TR 2” (J. M. Cline Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) This jug’s resemblance to the one attributed to John Wesley Carpenter in fig. 10—especially its tapered, fine-line reeded spout neck—suggests that Carpenter made it while working for Ritchie.

One-gallon jug, attributed to the John Wesley Carpenter pottery shop, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/4". Mark: incised “JWC 1” (numeral formed by a vertical series of dots). (Courtesy, Wilkes Heritage Museum, Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) This jug’s form differs enough from the one in fig. 10 to suggest that a different potter was engaged in its production for John Wesley Carpenter’s shop.

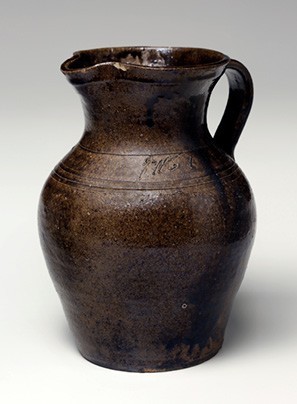

One-gallon pitcher, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 9 3/4". Mark: incised “JWC 1” (Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) The handle has been restored.

Two-gallon storage jar, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/4". Mark: incised “JWC 2” (John Haynes Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Four-gallon storage jar, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 13". (Carpenter Family Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) This jar was recovered from an abandoned cellar situated below a chicken coop on the John Wesley and Emily Carpenter farm. The Carpenter pottery shop in Pipers Gap made salt-glazed and alkaline-glazed stoneware.

Four-gallon jug, Daniel Seagle, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1850. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with reeded spout neck and glass runs. H. 16". (Ackland Fund, Ackland Art Museum, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 82.19.2; photo, Jason Dowdle Photography.)

Jug, David Hartzog, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1830–1840. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with glass and iron slip runs. H. 12 7/8". Mark: stamped “DAVIDHARTZOGHIMAKE” (The Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts [MESDA] at Old Salem, 5812.)

Reverse view of the jug illustrated in fig. 17, showing the glass run from the handle.

Three-gallon jug, Thomas Ritchie Pottery, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, second half of the nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 14 5/8". Mark: “TR 3” (Robert and Beverly Simpson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) The jug has incised bands of decorative straight and wavy lines similar to those seen on numerous Carpenter pottery wares.

Pan, attributed to Thomas Ritchie Pottery, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, third quarter of the nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware, H. 7", D. of rim 16". (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) This pan was ostensibly used by a Catawba Valley church for a Christian foot-washing ritual. Its form (especially its rim and handles) and decorative style suggest that John Wesley Carpenter was its maker, at his own or at Ritchie’s Catawba Valley shop.

Four-gallon storage jar, attributed to Thomas Ritchie Pottery, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, second half of the nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 12". Multiple marks, on handles: “4” (Robin and Kem Roberts Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) A stamped four-gallon mark used by John Wesley Carpenter is similar. The horizontal rim form, handle shape, and decoration are similar to what is observed on some John Wesley Carpenter wares.

Bottle, attributed to Marcus Ritchie (ca. 1851–1883), Catawba County, North Carolina, ca. 1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10 13/16". Mark: inscribed “M” (Danny Richard Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) The style of the letter M matches an “MR” signature inscribed on a line-decorated storage jar dated 1882 (not shown). Marcus was the son of Thomas Ritchie (1825–1909).

Two-gallon jug, attributed to Marcus Ritchie, Catawba County, North Carolina, dated 1882. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 16". Marks: inscribed “MR / 2” and “1882” (David Parker Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Left: Jug, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. H. 10 7/8". Mark: “JC 1” (L. A. and Suzan Rhyne Collection.) Right: Thomas Ritchie Pottery, Lincoln or Catawba County, North Carolina, second half of the nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with multi-line band of incised decoration below neck. H. 14 3/4". Mark: “TR 2” (Southern Folk Pottery Collectors Society Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

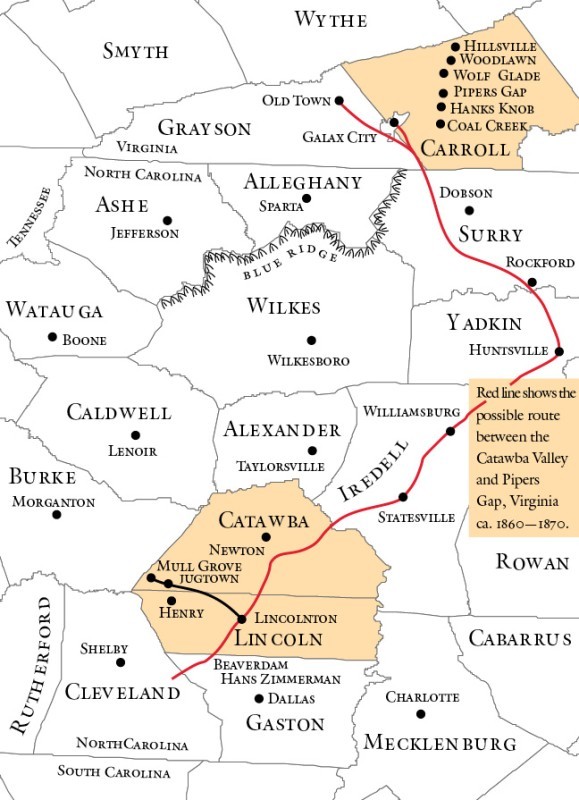

Map showing a conjectured route traveled by Carpenter family members from their Catawba Valley home to Virginia. The route shown was well traveled in the 1860–1870 period. Its path ran east of the mountains and passed through or nearby the town of Huntsville, where Moses Ritchie once resided and probably made pottery, before climbing in its last miles up the Blue Ridge escarpment to Pipers Gap.

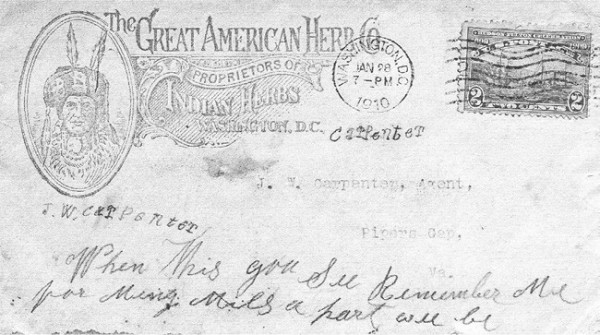

Postal envelope addressed to “J. W. Carpenter, Agent,” from the Great American Herb Company, Washington, D.C., dated January 28, 1910. (John Carpenter Collection.)

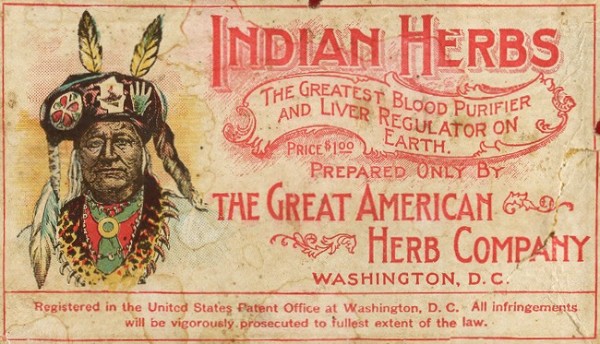

Box lid for Indian Herbs of the Great American Herb Company, Washington, D.C., ca. 1910. (John Carpenter Collection.)

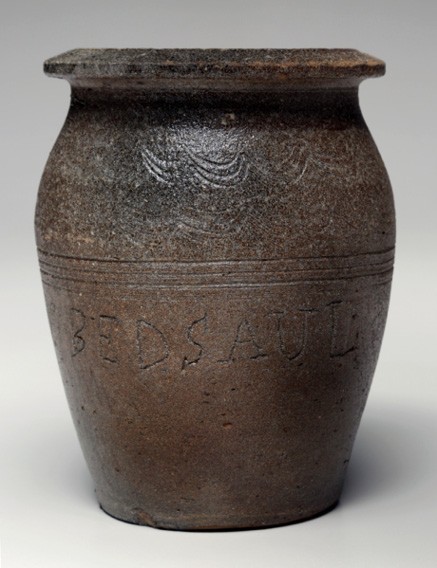

Jar, George Washington Bedsaul (1857–1889), Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, before 1884. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/8". Marks: incised “G. W. BEDSAUL”; incised “H” appears below the rim; and an indecipherable stamped mark, perhaps including the letter B, is impressed on the rim. (Phillip and Deborah Wingard Study Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) This jar’s distinctively sloped rim shape is found on some unsigned jars (see figs. 44, 45), suggesting that they represent Bedsaul’s work as well.

Left: One-gallon jug, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11". Mark: “JC 1” (Wesley Hall Collection.) Right: 1 1/2-gallon cream riser, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 7 1/2". Mark, on rim: “JC 1 1/2". (Courtesy, Wilkes Heritage Museum, Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) Some Carpenter salt-glazed stoneware is dark in color, perhaps due to the use of iron-laden clay. Some collectors mistakenly believe it was made in Wilkes County, North Carolina, where salt-glazed stoneware often looks the same. The dark coloration may have led John Wesley Carpenter to add white kaolin slip to greenware before firing it, to lighten its appearance.

Five-gallon jug, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 17 5/8". (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Five-gallon jug, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Lincoln County, North Carolina, ca. 1865–1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 17 1/2". Mark: “5” (gallons). (Brian Treverrow Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) A similarly inscribed “5” is found on the signed “JWC” jug illustrated in fig. 9.

Like the treadle wheel with a saddle-like seat used in John Wesley Carpenter’s Pipers Gap shop, this one is being used about 1931 by potter Albert Fulbright (b. ca. 1867) of Lincoln County, North Carolina. By contrast, most of North Carolina’s eastern Piedmont potters stood at the wheel, using a seatless version like those used in the vicinity of Chester County, Pennsylvania, where Quaker and Scots Irish potters prevailed. (Courtesy, Nowell Conan Guffey.)

The ca. 1912–1913 home of John Wesley and Emily Hanks Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Virginia, 2022. (Photo, Stephen C. Compton.) The Carpenter pottery was located nearby, over the hill beyond the house.

Robert Riggins (at left) and his cousin John Wesley Carpenter, great-grandsons of potter John Wesley Carpenter, stand above a pile of soapstone blocks cut by hand a mile away on Hanks Knob. (Photo, Stephen C. Compton.) First used in the construction of a kiln near John Wesley’s original home, they were used to build a chimney for his and his wife’s new house, illustrated in fig. 33. In 1989 remnants of Hurricane Hugo damaged the chimney, which led to its dismantling. The remaining kiln blocks have been stored nearby.

Detail of soapstone blocks once used in the Carpenter kiln. (Photo, Stephen C. Compton.) Close examination reveals evidence of thermal alteration, including deep discoloration, as seen here in a darkened band of stone. Melted kiln arch material has adhered to the edge of the soapstone block. Except for the inclusion of salting ports in its arch, the Pipers Gap kiln was identical to ones used in North Carolina’s Catawba Valley for making alkaline-glazed stoneware.

The Carpenter kiln site as it appeared in 2015. (Photo, January Costa.) A remnant of the large Catawba Valley-styled groundhog kiln extends into the hillside. Rocks, including some soapstone blocks, and bricks, are scattered about in the underbrush. John Wesley Carpenter removed most of the defunct kiln’s soapstone blocks around 1912 when constructing his new home’s chimney.

Storage jar with two lug handles, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, ca. 1868–1912. Stoneware with salt glaze over kaolin slip. H. 16". (Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Storage jar with four lug handles, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware glaze over kaolin slip. H. 17". (Kenneth Johnson Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Four-gallon jug, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware glaze over kaolin slip. H. 15 3/4". Mark: “JC 4” (John Carpenter Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

One-gallon jug, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. H. 11 1/4". Mark: “JC 1” (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Two-gallon storage jar, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. H. 11 7/8". Mark: “JC 2” (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) The vertical line dividing the jar’s slip coating suggests that the jar was dipped horizontally into a larger container filled with a slurry of kaolin slip.

Two-gallon storage jar, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/8". Mark: “JC 2” (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) In addition to salt-glazed stoneware, on special occasions John Wesley Carpenter produced alkaline-glazed stoneware like he once made in North Carolina. That he made both kinds at the same site, and perhaps using the same kiln, likely makes his operation unique among Southern and, more broadly, American potteries.

One-gallon storage jar, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, ca. 1868–1912. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/8". Mark: “JC 1” (L. A. and Suzan Rhyne Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Storage jar, attributed to George Washington Bedsaul, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, 1884. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 9 1/2". Mark: “1884” twice on rim. (Colonial Williamsburg Art Museums; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Storage jar, attributed to George Washington Bedsaul, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, ca. 1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with glass runs. H. 9 3/4". (William C. and Susan S. Mariner Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.) The use of glass fragments for decoration is to some extent a common practice among North Carolina’s Catawba Valley alkaline-glaze stoneware makers.

Detail of the storage jar illustrated in fig. 45, showing glass decoration as it was applied to the handles.

Jug, John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, dated 1881. Stoneware with salt glaze over kaolin slip. H. 8". Marks: inscribed “J.W.C.” and “1881” (Carpenter Family Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) Several objects decorated in this fashion are known. In addition to John Wesley Carpenter’s initials and the date, this example includes stylized crosses, a pine tree, and a male figure.

Pitcher, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, ca. 1881. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. H. 7 1/4". Mark: “E. M. Carpenter” (Carpenter Family Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) John Wesley and Emily Hanks Carpenter were married in 1880. This piece displays crosses, pine trees, and a whirligig-type figure. The decorator is unknown.

Pitcher, attributed to John Wesley Carpenter, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, ca. 1881. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. H. 6 7/8". (Wesley Hall Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) This piece displays crosses, a pine tree, and a whirligig-type figure like the one seen on the pitcher illustrated in fig. 48.

Three-gallon storage jar, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, late nineteenth to early twentieth century. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. H. 11". Mark: stenciled “J.W. C. 3” with cobalt smalt. (Carpenter Family Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

One-gallon jug, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, late nineteenth to early twentieth century. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. H. 10 1/4". Marks: stamp-impressed “JC 1”; stenciled “J.C. 1” (Wesley Hall Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Gravestone fragment, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, late nineteenth to early twentieth century. Salt-glazed stoneware over kaolin slip. 6 x 4 3/4 x 2 3/16". Mark: stenciled “J • C.” with cobalt smalt. (Carpenter Family Collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.)

Detail of a four-gallon jar, Carpenter Pottery, Pipers Gap, Carroll County, Virginia, last quarter of the nineteenth century. H. 15". Mark: stamped “JC 4” on rim. (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) Harking back to decorations added to Catawba Valley–made alkaline-glazed wares, especially those associated with Thomas Ritchie’s pottery, the Carpenter shop potters often added these combined straight- and wavy-line incised patterns to their pottery. Absent a “JC” or “JWC” mark, such embellishments often reliably substitute for a Carpenter shop signature.

Vessels, attributed to Poley Carp Hartsoe (1876–1960), Catawba County, North Carolina, first half of the twentieth century. Albany slip and alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. of tall jug 11", h. of small jug 3 1/4", h. of pitcher 2 7/8". (Author’s collection; photo, Tim Barnwell Photography.) Even into the early years of the twentieth century, North Carolina’s Catawba Valley potters applied incised line decoration to their vessels’ surfaces. The practice is common among potters associated with the Seagle, Hartzog, and Ritchie family potteries, including members of the Carpenter and Johnson families. Poley Carp Hartsoe was the son of potter Sylvanus Leander Hartsoe (1850–1926) and grandson of potter David Hartzog (1808–1883).

Detail of the jug illustrated in fig. 9. John Wesley Carpenter knew how adding bits of glass to glazed ware before firing could produce dramatic decorative highlights like this one, seen here in a detail from a masterpiece jug signed with his initials, as if to declare with pride, “I made this.” It seems that he mostly abandoned the practice after moving to Virginia.

Detail of the glass run illustrated in figs. 9 and 55.