Ring bottle, attributed to Edward and Robert Stork Pottery, Columbia, South Carolina, 1888. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10". (Chipstone Foundation; all photos by Robert Hunter unless otherwise noted.) The hollow ring that forms the body was thrown on the wheel from a single ball of clay. The neck/mouth was thrown in a separate operation. The solid rectangular base was molded by hand. These components were assembled at the leather-hard state of the clay. The handle was pulled separately and attached to the body.

Inscription on the base of the ring bottle illustrated in fig. 1: “Dr. Peter / Davis / 1888”

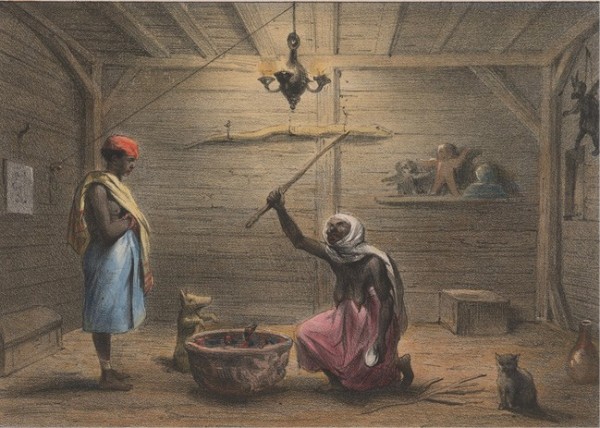

Jean-Baptiste Madou (1796–1877) and Pierre Jacques Benoit (1782–1854), La Mama-snekie, ou water-mama, faisant ses conjurations (1839), p. 36. Voyage a Surinam: Description des possessions Néerlandaises dans la Guyane (Brussels: Société des Beaux-Arts, 1839). Colored lithograph on paper. 8 1/4"x 11 3/8". (John Carter Brown Library, Brown University.)

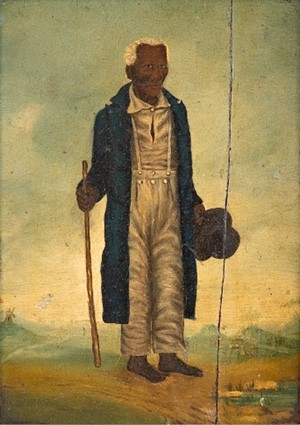

Unknown artist, Obeah Man, probably Jamaica or Barbados, ca. 1830. Oil on mahogany panel. 7 1/4"x 5 1/4". (Private collection.)

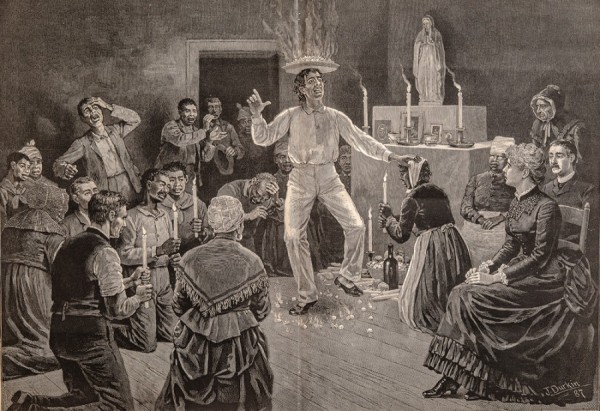

“A Voudoo Dance,” drawn by John Durkin, Harper’s Weekly, June 25, 1887, pp. 456–57. Uncolored engraving. 16 x 22". (Private collection.)

Book cover, Old Rabbit, the Voodoo, and Other Sorcerers by Mary Alicia Owen, illustrated by Juliette A. Owen and Louis Wain (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1893).

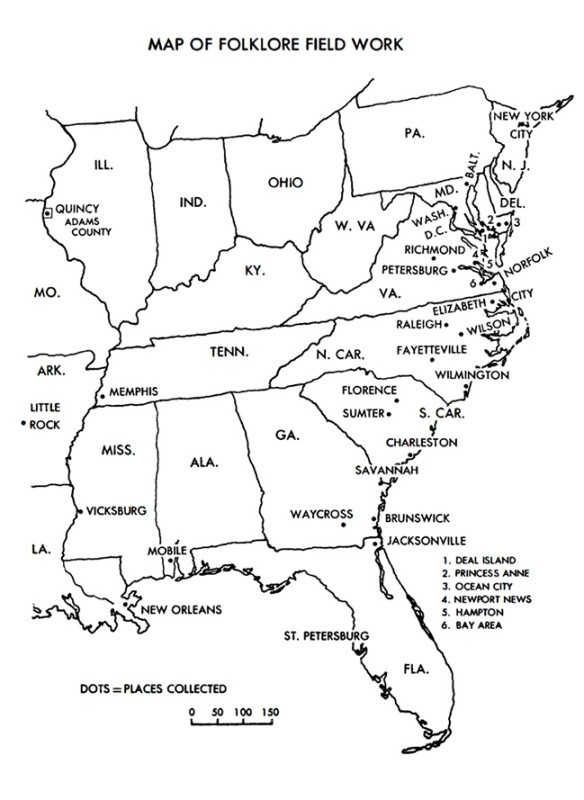

“Map of Folklore Field Work,” from Harry Middleton Hyatt, Hoodoo—Conjuration—Witchcraft—Rootwork: Beliefs Accepted by Many Negroes and White Persons, These Being Orally Recorded among Blacks and Whites, Memoirs of the Alma Egan Hyatt Foundation 5: frontispiece ([Hannibal, Mo.]: Printed by Western Pub., 1978).

Ring flask, Cypro-Geometric III–Cypro-Archaic I, 850–600 b.c. Terracotta. H. 6 3/4". (Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cesnola Collection, Purchased by subscription, 1874–76, 74.51.651.)

Ring bottle, New York, New York, ca. 1800–1830. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/2". (New-York Historical Society, Purchased from Elie Nadelman, 1937.579.)It is decorated with incised hearts, fish, birds, and the initials “M.S.”

Ring bottle, attributed to the Landrum Pottery, Richland County, South Carolina, ca. 1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/8". (Chipstone Foundation.)

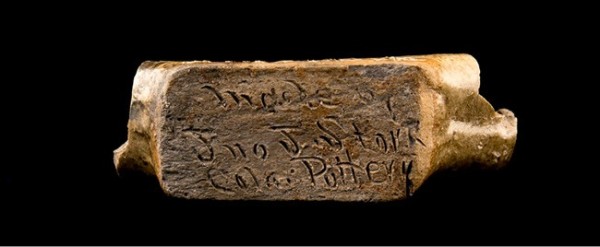

Archaeological fragment of ring bottle, John Stork Pottery, Columbia, South Carolina, ca. 1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. Inscribed on ring, “John J. Stork” (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

Detail showing the base of the ring bottle fragment illustrated in fig. 11. Inscribed “made by / Jno J. Stork / Col. Pottery”

Detail showing the dark, iron-rich glaze of the ring bottle illustrated in fig. 1.

Ring bottle, Edward L. Stork, Orange, Georgia, ca. 1909. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/2". Impressed: “E.L. STORK / ORANGE, GA.” (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation.)

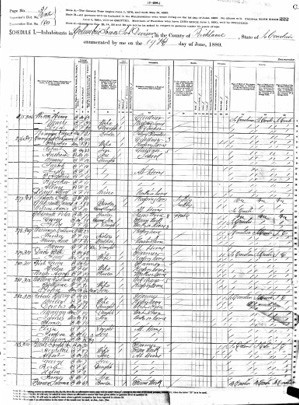

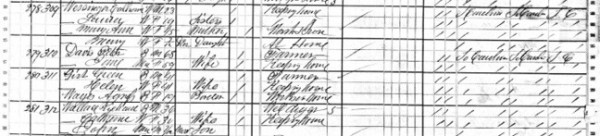

1880 Federal Census, “Inhabitants in Columbia Lower Sub Division in the County of Richland, State of South Carolina, June 14, 1880.”

1880 Federal Census entry for Peter Davis as a Black male, age 68, occupation farmer, and listing his birthplace and that of his parents as South Carolina.

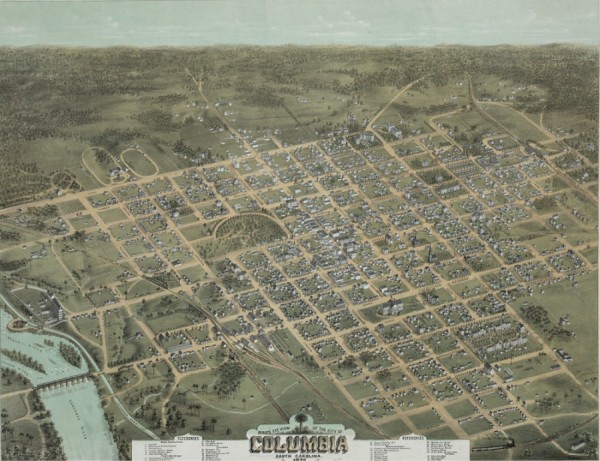

C. N. Drie, Bird’s Eye View of the City of Columbia, South Carolina (Baltimore, Md., 1872). Colored lithograph on paper. 21 1/4x 27 1/2". (Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C., 2008675451.)

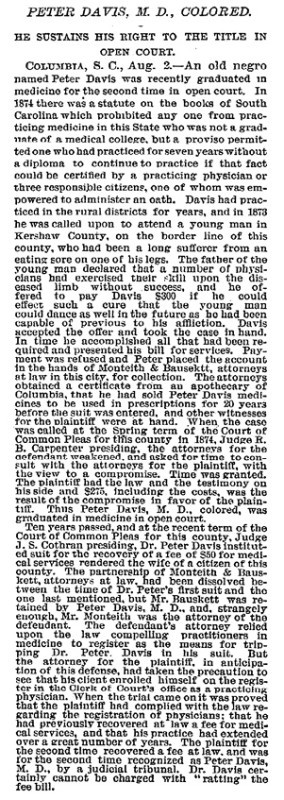

“Peter Davis, M.D., Colored. He Sustains His Right to the Title in Open Court,” New York Times, August 3, 1884, p. 7.

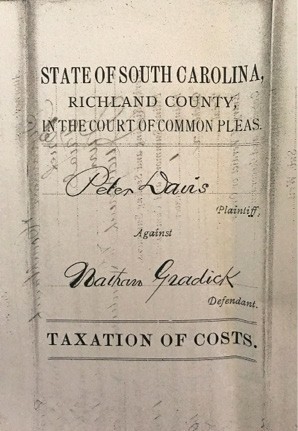

Peter Davis vs. Nathan Gradick, Taxation of Costs, State of South Carolina, Richland County, in the Court of Common Pleas, July 21, 1884.

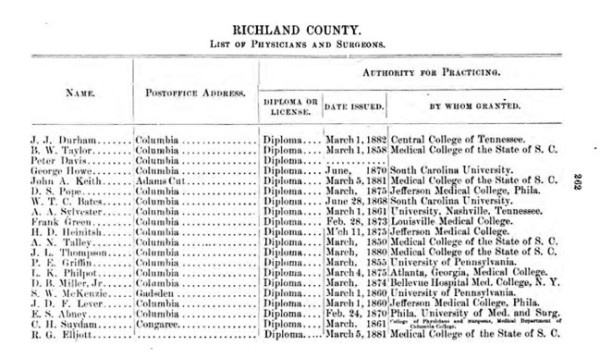

“List of Licensed Physicians and Surgeons of the State” (Richland County, South Carolina), Reports and Resolutions of the General Assembly of South Carolina, at the Regular Session Commencing November 23, 1886, Vol. 2 (Columbia, S.C.: Charles A. Calvo Jr., State Printer, 1887), p. 262. Available online at https://www.carolana.com/SC/Legislators/Documents/.

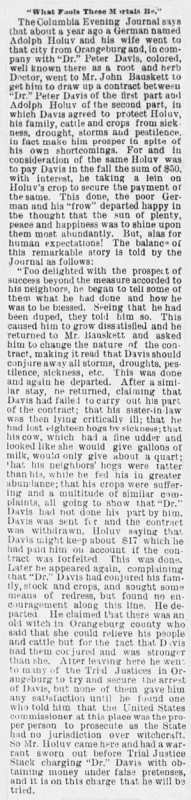

“What Fools These Mortals Be,” The Times and Democrat (Orangeburg, S.C.), July 19, 1893, p. 8.

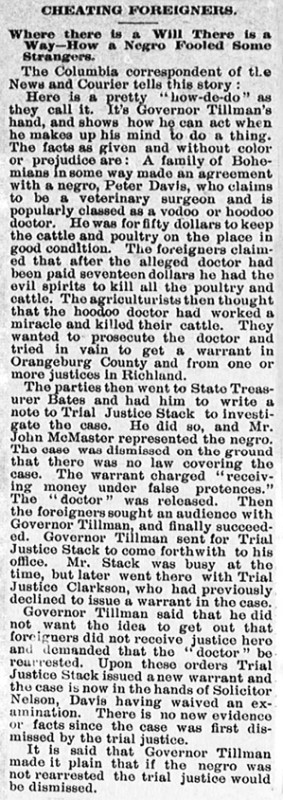

“Cheating Foreigners,” The Laurens (S.C.) Advertiser, October 10, 1893, p. 4.

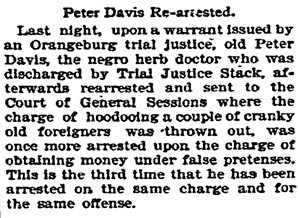

“Peter Davis Re-arrested,” The State (Columbia, S.C.), October 25, 1893, p. 8.

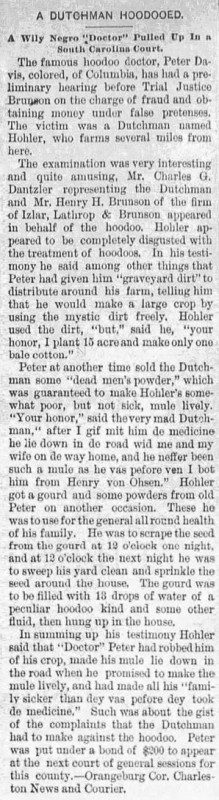

“A Dutchman Hoodooed: A Wily Negro ‘Doctor’ Pulled Up in a South Carolina Court,” Charlotte (N.C.) News, November 15, 1893, p. 3: “Peter had given him ‘graveyard’ dirt to distribute around.”

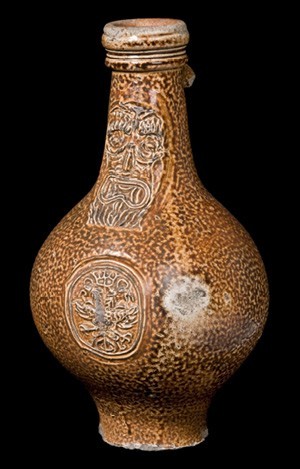

Bartmann or Bellarmine bottle, Frechen, Germany, ca. 1650–1680. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, 1910.18.1.) This vessel was recovered in 1904 during excavations in Westminster, London, and donated to the Pitt Rivers Museum by Edward Warren. Once sealed with a cork, its contents suggest it was used as a “witch bottle.” For more information, see http://objects.prm.ox.ac.uk/pages/prmuid25735.html.

Contents of the bottle illustrated in fig. 25, which include a coarse-fabric cloth heart stuck with straight pins, human hair and fingernail clippings, and a cork stopper. (Courtesy, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, 1910.18.2–4.) For more information, see https://www.museumof london.org.uk/discover/sorcery-display-witch-bottles.

Fragmentary glass wine bottle and associated contents. (Courtesy, Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab, Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum.) An example of an eighteenth- or nineteenth-century witch bottle burial was found at the White Oak site in Dorchester County, Maryland. A wine bottle neck, horseshoe, bottle glass sherds, and bone fragments were beside a brick hearth. Several straight and bent pins had been inserted into a solid stopper in the bottle neck, both on the inside and outside of the bottle.

Face vessels, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1850–1860. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. of the tallest 5 1/2". (Private collections.)

Detail of the face vessel illustrated on the left in fig. 28 showing traces of red pigment for the eyes and pupils.

Detail of the face vessel illustrated on the right in fig. 28 showing the hole in the bottom.

Ointment or salve jar, possibly Virginia, Maryland, or Pennsylvania, ca. mid-nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 3 3/8". (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation.)

Illustration of Angelica archangelica (Archangelica officinalis), commonly known as garden angelica or wild celery. Chromolithograph on paper. 8 x 10". From Köhler’s Medicinal Plants, by Hermann Adolph Köhler, edited by Gustav Pabst (Germany: Köhler, 1887). (Author’s collection.)

Detail of the jar illustrated in fig. 31.

Flask, American or possibly Asian, nineteenth century. Stoneware with cobalt decoration. H. 5 3/4". (Courtesy, Rick Meech Burchfield.)

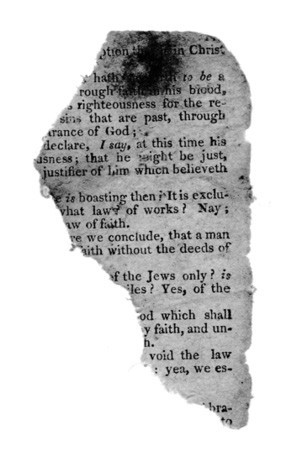

Fragment of a page from a King James Bible, probably nineteenth century. It contains partial verses from Romans 3:25–31.

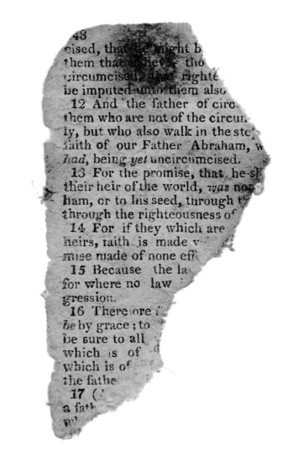

Reverse of the page fragment illustrated in figure 35. It contains partial verses from Romans 4:11–17.

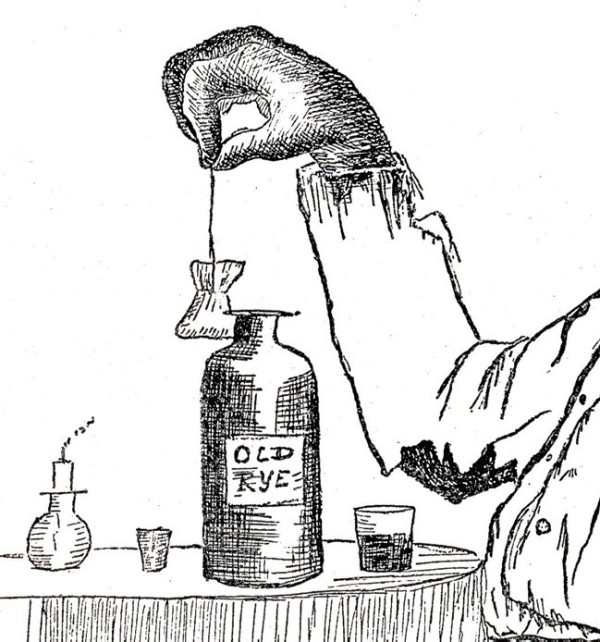

Detail of the 1893 King of the Voodoos engraving illustrated in fig. 39. This 1893 detail emphasizes the use of whiskey as one of the primary ingredients in a variety of hoodoo rituals.

Immagine del manoscritto Zoroaster Clavis Artis, MS. Verginelli-Rota, Biblioteca dell’Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Roma, 2:18 (1738). (Photo, The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo.)

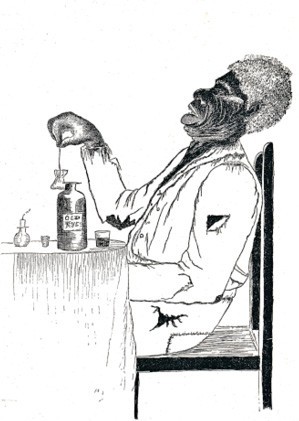

Louis Wain, “King of the Voodoos,” in Owen, Old Rabbit, the Voodoo, and Other Sorcerers (1893), p. 172.

“The Blackville Gallery,—No. IV,” Leslie’s Weekly, January 20, 1898, pp. 40–41. Copyright by Knaffl & Bro., Knoxville, Tennessee, 1898. Photogravure. 22 x 16". (Author’s collection.) The image shows a fortune teller reading the palm of a society lady as the fortune teller’s partner smokes a long pipe next to the fireplace. The caption under the title reads, “A Blackville Fortune Teller,”—“Lawd, Chile! Yo Gwine to Marry Rich.”

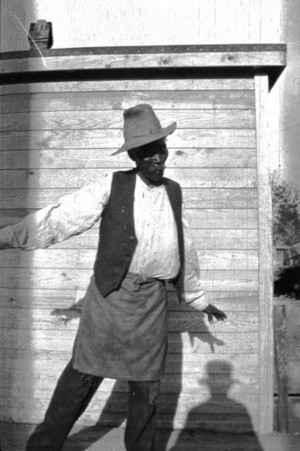

“Mississippi Hoodoo Doctor,” 1920–1940. Gelatin silver print. From Photographs from the Puckett Collection: Folk Beliefs of African Americans in the Southern United States. (Cleveland Public Library, Fine Arts and Special Collections Department; photo, Newbell Niles Puckett.)

Conjure objects from the practice of Mrs. Mamie Wade Avant DeVeaux of Savannah, Georgia, mid-twentieth century. (Mamie Wade Avant DeVeaux Archive.) The objects include a string of beads and dice, playing cards, a heart-shaped mojo bag, and a container of “Blue Stone” (copper sulfate.) Bluestone is a traditional magical substance used for making mojo hands and luck balls for protection and good luck.

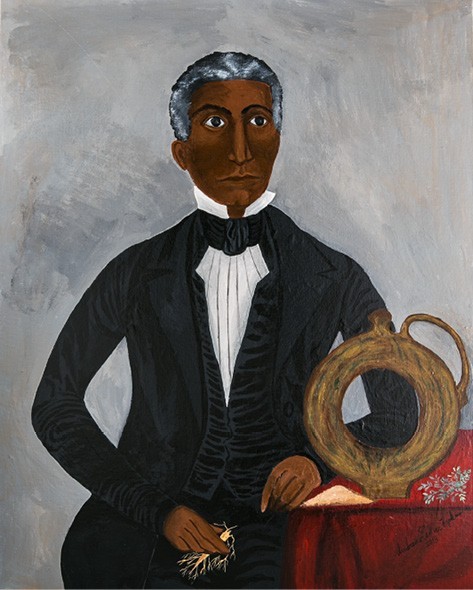

Andrew Hopkins, Dr. Peter Davis, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2017. Acrylic on board. 16 x 20". (Author’s collection.)

Andrew Hopkins, Marie Laveau, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2017. Acrylic on board. 16 x 20". (Author’s collection.)

Anvil dust sourced from Colonial Williamsburg’s blacksmith shop. Anvil dust, the metallic residue created during the blacksmith’s forging process, figures prominently in the practice of conjure and hoodoo. The 1928 Ma Rainey tune “Black Dust Blues” is a classic tale of “goofering,” a synonym for hoodooing. In it, Ma Rainey sings “Black dust in my window, black dust on my porch mat / Black dust’s got me walking on all fours like a cat.”

Modern-day hoodoo materials—including hoodoo water, graveyard dirt, deadmen’s powder, lodestones, gourds, and “roots”—alongside a replica of Dr. Davis’s ring bottle. Those ingredients were used in the “treatment” of Adolph Holuv and his family as gleaned from the newspaper accounts of Dr. Davis’s 1893 court proceedings. (Private collection.)

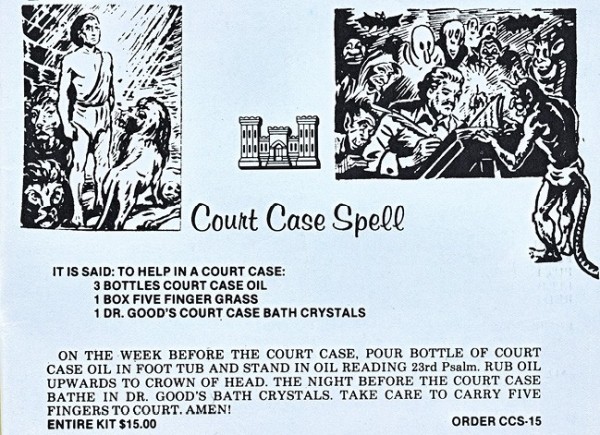

“Court Case Spell” (Order CCS-15), Ritual Supplies Mail Order Source Occult Supplies!, ca. 1960–1970. (Mamie Wade Avant DeVeaux Archive.) A page from a catalog for Miller’s Rexall Drugs, 87 Broad Street, S.W., Atlanta, Georgia, 30303.

Court Case Spell Kit, Lucky Mojo Curio Co., Forestville, California. Powders, oil, mojo bag, and nine candles. (Author’s collection.)

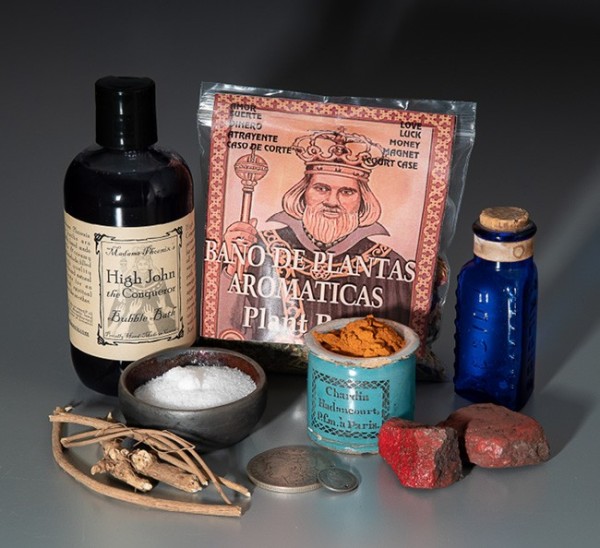

A group of hoodoo objects and ingredients mentioned in “Folk-Tales and Conjure,” Southern Workman and Hampton School Record 28 (March 1899): 112. (Author’s collection.) The “Remedies to Cure Conjuration” include High John the Conqueror plant bath, salt, cayenne pepper, devil’s shoestring roots, red lodestone, and nineteenth-century American silver coins.

“Dr.” Peter Davis . . . a cross between a gorilla and a badger and a lineal descendant of one of the witches of “Macbeth.”[1]

—“The Hoodoo Doctor,” Camden (S.C.) Chronicle,

November 10, 1893, p. 1.

WHEN THE AUDIENCES OF William Shakespeare’s Macbeth (ca. 1606) first heard the Three Witches recite their famous lines “Double, double toil and trouble / Fire burn and cauldron bubble,” the inner workings of witchcraft and sorcery were well embedded in the Jacobean zeitgeist. King James I himself had already published Daemonologie, his treatise on “black magic,” in both Scotland (1597) and London (1603), and his subjects knew him as a staunch opponent of the practice.[2] To counter bewitchment, various apotropaic or protective magical spells incorporating the use of talismans, amulets, potions, bones, and powders were in vogue in all ranks of British society. Shakespeare may have drawn directly from well-known conjurations circulating in the populace when he included “Eye of newt and toe of frog” as ingredients in the witches’ brew.[3]

Gonna sprinkle ding ’em dust all around her door. . .

Some four hundred years later in America, another mysterious charm was delivered to listeners of Bessie Brown’s music when she sang the lyrics to her composition “Hoodoo Blues” (1924):

Gonna sprinkle ding ’em dust all around her door

Gonna sprinkle ding ’em dust all around her door

Put a spider in her dumplin’, make her crawl all over the floor

Goin’ ’neath her window, gonna lay a black cat bone

Goin’ ’neath her window, gonna lay a black cat bone

Burn a candle on her picture, she won’t let my good man alone.[4]

American blues musicians had become the troubadours of “hoodoo,” a tradition of magical thinking in the quest for supernatural interventions. Variously called conjuring, rootwork, and often conflated with the term voodoo, hoodoo has been of great interest to chroniclers of American social history. Traces of its material-culture component are scarce; much of its history is documented through newspaper accounts, oral histories, and archaeological research. What follows is a tale worthy of Shakespeare: the finding of an American Southern stoneware object that provides both a physical and metaphysical portal into the history of American hoodoo.

The Discovery

On October 10, 2017, a nineteenth-century American stoneware ring bottle came up for sale in a midweek auction in Columbia, South Carolina (fig. 1).[5] The ring bottle (sometimes called a jug or flask) was a somewhat common Southern vessel form made in a number of regional potteries from the late eighteenth century onward. The example presented at auction, however, was distinguished by the addition of a graceful handle

and a sturdy rectangular base so that it could stand upright. The bottle was covered in a streaky, iron-rich slip glaze generally characteristic of the Columbia area. It was brought to my attention because the unglazed base was inscribed “Dr. Peter Davis” along with the date “1888” (fig. 2). That elevated an attractive but not particularly unusual Southern ceramic form to one of considerable rarity, since inscriptions of this type are generally not found on surviving antique examples. No other historical information was offered at the time of the sale.

The Columbia auction house was a small, regional business dealing in household liquidations and estates. Not so long ago its offerings would have reached a relatively limited audience, yet all that has changed in the age of the Internet and social media. Someone in the cadre of Southern pottery collectors had spied the bottle, and before long its existence was known throughout the network of Facebook groups that seek such finds. I reached out to my colleague Phil Wingard, who lives within an hour and a half’s drive of the auction house. After discussing the object’s merits, Phil agreed to travel the distance to preview the bottle and to buy it at that evening’s sale. When he arrived, Phil found the bottle nestled among the boxes of household bric-a-brac slated for the auction block—and, to his dismay, a veritable who’s who of Southern pottery collectors in the audience. Undeterred, Phil and I settled on an aggressive bid. We were outbid by a considerable factor, however, and a local collector, to the astonishment of the midweek attendees accustomed to spending tens of dollars not tens of thousands, took home the prize.

Several days later, the ring bottle became the focus of a Facebook specialty group with many admiring “likes” and congratulations for the new owner. As is often the case in such groups, the owner was soliciting insight from the collective minds of stoneware aficionados: “Any info on Dr. Peter Davis would be great. . . . .I think maybe Union SC. . . . .but not sure.” One of the respondents was Corbett Toussaint, a collector and historical researcher of the nineteenth-century South Carolina stoneware industry. Her first observation was “I see a ‘Dr’ Peter Davis in the Columbia newspaper in the 1890s who was arrested for performing ‘Hoo Doo’ on other people.”

That comment hit me like a bolt of lightning. My interest in the ritual use of Southern ceramics has percolated for nearly thirty years, first as an archaeologist investigating the meaning of African-American charms and ceremonial objects recovered from historical contexts, and later in the proposition that the antebellum Edgefield face jugs were associated with African spiritualism and conjure.

A subsequent dive into various newspaper accounts further described Dr. Davis as “colored” and an active “root doctor,” “herbalist,” “conjuror,” “hoodoo doctor,” and “voodoo doctor,” depending on the source. Beginning in 1893 and continuing into early 1894, Dr. Davis’s legal troubles were reported in South Carolina newspapers and in nationally distributed papers as far away as Hawaii.[6] The ring bottle took on new significance as the only verifiable American ceramic object directly associated with nineteenth-century American hoodoo.

Southern Hoodoo or Conjure

The practice of hoodoo is one of many overlapping folk traditions that combine ritual and materials to connect with external cultural or spiritual forces. At its most basic, I think of hoodoo as “wishful thinking.” For example, blowing out birthday candles and making a wish could be described as a simple folk-magic ritual. On a larger historical and cultural level, however, defining hoodoo is anything but simple.

Hoodoo is not a religion, but it is informed by underlying African, Christian, and Native American religious beliefs. The term conjure is often used interchangeably, particularly before emancipation. The practice, which incorporates rituals, objects, and a wide range of natural oils, herbs, plants, roots, salves, and powders, is an integral part of the African-American historical fabric from the early days of slavery to present times.[7]

Other magical traditions often are conflated or confused with American hoodoo, such as Obeah and Vodou.[8] Obeah is a term for a system of spiritual and physical healing that developed among West African–enslaved populations of the West Indies (figs. 3, 4).[9] Vodou or Voodoo refers to religious rites and beliefs that evolved in Haiti between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries as new African immigrants arrived. The term voodoo is more commonly used in the American South, usually associated with New Orleans (fig. 5).[10] Powwow, also called “Brauche” in German or “Braucherei” in Pennsylvanian Dutch, is a system of herbal remedies and magic that developed among the German immigrant populations of North America.[11]

The evolution of what is now called hoodoo in America begins with the influx of enslaved Africans directly from Africa and those influenced by Caribbean religions. Prior to emancipation, conjuring was central to the lives of the enslaved populations, particularly those serving on plantations.[12] Nineteenth-century texts known as “slave narratives” demonstrate the power that the conjurer held over both the enslaved communities and, at times, the white oppressors.[13] Historian John Blassingame contends that “the conjurer had more control over the slaves than the master had.”[14] One writer, Henry Walton Bibb (1815–1854), an American author and abolitionist who was born a slave in Kentucky but escaped to Canada in 1842, observed that “conjuration, tricking, and witchcraft” were indispensable to enslaved plantation workers. Bibb identified specific ingredients and prescriptions: “The remedy is most generally some kind of bitter root; they are directed to chew it and spit towards their masters when they are angry with the slaves. At other times they prepare certain kinds of powders, to sprinkle about their masters’ dwellings.”[15]

Another account was written by William Wells Brown, who was born into slavery in Montgomery County, Kentucky, but fled to Ohio in 1834 at the age of nineteen. He ultimately became a prominent advocate and author in the cause of abolitionism. In his writings, Brown claimed that “nearly every large plantation . . . had at least one [conjurer], who claimed to be a fortune-teller, and who was regarded with more than common respect by his fellow-slaves.”[16]

Famed abolitionist and former slave Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) wrote of his solicitation for protection against harsh beatings.[17] The conjurer, whom Douglass identified as “an old advisor” and a “genuine African, [who] had inherited some of the so called magical powers, said to be possessed by African and eastern nations.”[18] While remaining skeptical, Douglass acquiesced to carry the prescribed “root of the herb” in his pocket and ultimately acknowledged it had offered some defense against excessive whippings.

Often overlooked in the rush to investigate African-American supernatural rituals was the medicinal value of conventional herbal remedies.[19] Enslaved men and women served as caregivers and health practitioners for their communities, drawing on African, Caribbean, European, and Native American folk pharmacological knowledge using herbs, minerals, plants, and roots.[20] Faith in the sacred was vital in the success of the root doctor, not just a knowledge of the natural world. Sharla M. Fett, in her book Working Cures, underscores that the work of the root doctor was equally “spiritual and practical.”[21]

With the advent of emancipation, hoodoo was transformed into what Katrina Hazzard-Donald calls “old tradition black belt Hoodoo,” a folk system of spiritual belief, medicine, and control.[22] It was in this era that the word came into everyday usage. A lengthy three-part article that appeared in the Memphis Daily Appeal on October 25, 1868, is the first published discourse on the topic:

Vaudooism

African Fetish Worship Among The Memphis Negroes

A Little White Girl the Victim

The word Hoodoo, or Vaudoo, is one of the names used in the different African dialects for the practice of the mysteries of the Obi (an African word signifying a species of sorcery and witchcraft common among the worshippers of the Fetish). In the West Indies the word “Obi” is universally used to designate the priests or practices of this art, who are called “Obi” men and “Obi” women. In the southern portion of the United States—Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, South Carolina and Georgia—where the same rites are extensively practiced among the negroes, and where, under the humanizing and Christianizing influence of the blessed state of freedom and idleness in which they now exist and are encouraged by the Freedmen’s Bureau, the religion is rapidly spreading. It goes under the name of Vaudooism or Hoodooism. The practicers of the art, who are always native Africans, are called hoodoo men or women, and are held in great dread by the negroes, who apply to them for the cure of diseases, to obtain revenge for injuries, and to discover and punish their enemies. The mode of operations is to prepare a fetish, which being placed near or in the dwelling of the person to be worked upon (under the doorstep, or in any snug portion of the furniture) is supposed to produce the most dire and terrible effects upon the victim, both physically and mentally. Among the materials used for the fetish are feathers of various colors, blood, dog’s and cat’s teeth, clay from graves, egg-shells, beads, and broken

bits of glass. The clay is made into a ball with hair and rags, bound with twine, with feathers, human, alligators’ or dogs’ teeth, so arranged as to make the whole bear a resemblance to an animal of some sort. The person to be hoodooed is generally made aware that the hoodoo is “set” for him, and the terror created in his mind by this knowledge is generally sufficient to cause him to fall sick, and (it is a curious fact) almost always to die in a species of decline. The intimate knowledge of the hoodoos of the insidious vegetable poisons that abound in the swamps of the South, enables them to use these with great effect in most instances.[23]

The Southern Workman, a monthly journal distributed by the Hampton Institute in Virginia, published African-American and Native American folklore beginning in 1872. Those essays represent some of the first attempts in which Black Americans recorded and classified their own culture’s conjure rituals.[24] What might be the earliest listing of spells appeared in 1899 in the Southern Workman and Hampton School Record, written by an anonymous Hampton student:

Get grave-yard dirt and put it into the food or sprinkle it around the lot. It will cause heavy sickness. Have a vial, put into it nails, red flannel, and whiskey. Put a cork in it, then stick nine pins in the cork. Bury this where the one you want to trick walks.[25]

In 1893 Mary Alicia Owen (1850–1935), a white writer, published Old Rabbit, the Voodoo, and Other Sorcerers, stories based on her experiences with Native American and African-American conjurers in her hometown, St. Joseph, Missouri (fig. 6).[26] She wrote using customary albeit stereotypical Southern Black dialect.[27]

Articles on hoodoo, conjure doctors, and rootworkers appearing in newspapers through the 1920s were often sensationalized accounts that underscored prevailing and disparaging racial stereotypes. Indeed nearly all accounts are of African-Americans, although occasionally white hoodoo doctors appear.[28] The stories generally portray these figures as tricksters, hucksters, and charlatans, and typically refer to their clients as victims.[29]

African-American folk magic became the subject for serious investigators beginning in the early twentieth century. Born and raised in Mississippi, for example, Newbell Niles Puckett (1898–1967) developed an interest in the local African-American culture, which led to his research focused on the belief systems of African-Americans in the South. He conducted fieldwork by interviewing residents of Lowndes County, Mississippi, about spiritual songs, graveyard decorations, conjuring spells, and various folk-medicine recipes. In 1926 Puckett published Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro, an expanded version of his doctoral dissertation. He also created a remarkable photographic archive of conjurers, root doctors, and related paraphernalia that is now maintained by the Cleveland Public Library.[30]

Another influential ethnographer and prolific writer was Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960), who was born in Notasulga, Alabama, and raised in Eatonville, Florida.[31] Trained in anthropology at Barnard College and Columbia University, Hurston is regarded as the most important Black writer to collect firsthand accounts of conjure and rootwork. Her lengthy article “Hoodoo in America,” published in 1931, includes tales of Marie Laveau and firsthand interviews with contemporary hoodoo doctors. She even took lessons in hoodoo, learning the materials and rituals for spells such as “Business Success,” “Court Scrapes,” “Love,” and “To Kill.”[32] Her 1935 book Mules and Men focuses on her excursions to New Orleans and Alabama to record African-American stories, songs, superstitions, and detailed descriptions of the hoodoo practice.

A massive archive of hoodoo and conjure spells recorded by Harry Middleton Hyatt (1896–1978) from African-American informants resulted in a 4,666-page, five-volume publication, Hoodoo –Conjuration –Witchcraft –Rootwork.[33] Hyatt was an ordained Anglican priest but had a passionate interest in African-American folklore.[34] Published in 1970, the archive consists of 13,458 separate magic spells, folktales, and anecdotes that come directly from practitioners in twelve different states (fig. 7). Hyatt observed that “hoodoo is an amorphous body of rites and substances continually changing. . . . Its conglomerate nature made it difficult to grasp as a whole.”[35]

Twenty-first-century scholars continue to explore the topics of hoodoo, conjure, and rootwork.[36] The bibliography for such studies is extensive, and spans the fields of anthropology, archaeology, folklore, social and religious histories, African-American studies, ethnography, and musicology.[37] The practice also remains very much alive, as evidenced by the large body of how-to literature, conjuring supplies, and vast Internet and social media resources.[38] A prolific writer and supplier is Catherine Yronwode, who runs an online business, the Lucky Mojo Curio Company (luckymojo.com), a maker and distributor of hoodoo and conjure supplies.[39]

Southern Ring Bottles

Ring bottles are an iconic Southern ceramic form, produced in both earthenware and stoneware by many different potters from Texas to Virginia. The form originated in classical antiquity, and later appears in medieval and modern Europe (fig. 8). The small number of the American-made examples that survive inscribed with initials and dates suggests that ring bottles held special significance for the makers as well as the end users (fig. 9). The ring bottle remains a staple of Southern folk potters and continues to be a prized production item.[40]

A ring bottle of the same general form as the Dr. Davis example is owned by the Charleston Museum, where it is attributed to the ca. 1850–1880 -Linneaus Landrum Pottery of Richland County, South Carolina; another is in the collection of the Chipstone Foundation (fig. 10).[41] The Landrum Pottery was first established by Abner Landrum in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, and after his death in 1859 was owned by his son Linneaus.

Archaeological fragments of a similar ring bottle have been found at the Landrum Pottery site; they are inscribed “John J. Stork” and “Made by /Jno J. Stork / Col. Pottery” (figs. 11, 12).[42] John J. Stork was the son-in-law of Abner Landrum and worked at the pottery. Stork later operated his own pottery in the Dentsville community just outside of Columbia. There his sons Edward Leslie and Robert Manning transitioned from the lighter color ash and lime glaze to a dark, almost black iron-rich glaze (fig. 13).[43] The 1888 date on the Dr. Davis ring bottle corresponds with the Stork sons’ tenure at the Dentsville pottery. Edward left that pottery around 1900 and worked at several different potteries in Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia. By 1909 he had established his own workshop in Orange, Georgia, where apparently he continued to produce the form (fig. 14).[44]

Who Was Dr. Peter Davis?

A full biography of the man has yet to be written; what we know is based on a few legal records and a rather large number of newspaper accounts published from New York to California in the 1893–94 period. Census records show that Peter Davis (1812–1911) was born in South Carolina around 1812 (figs. 15, 16).[45] There is no indication whether he and/or his parents were enslaved and we know that Columbia did have a small community of free Blacks.[46] His wife, Jane, is listed in the 1880 census as age 59, and her occupation as “Keeping home.” Peter is listed as “Farmer,” even though he resided in Columbia’s 3rd Ward, a developed urban setting outlined in figure 17.[47] He signed the 1882 voter roll with his “X” mark, which suggests that he was illiterate. No children are recorded.

Columbia served as the state capital beginning in 1786 and grew steadily; when it was chartered as a city in 1854, it had the largest population in the Carolinas. With an economy based on the processing of cotton, available records show that 1,500 enslaved people were in residence in 1830, and by 1860 that number had risen to 3,300. After emancipation, this large, predominantly enslaved African-American population transformed itself into a community of social, political, and economic power.[48]

An 1884 New York Times article—“Peter Davis, M.D., Colored. He Sustains His Right to the Title in Open Court”—recounts a Columbia court case where Davis was suing for the “recovery of a fee for $50 for medical services rendered the wife of a citizen of this county” (fig. 18). In preparation for this article, researcher April Hynes undertook a review of the legal documents pertaining to the case, which showed that Dr. Davis was successfully awarded $50.00 plus $33.70 in court costs (fig. 19). From the Times article we also learn that Dr. Davis had no formal medical training but, through some legal maneuvering by his lawyers, had been previously awarded legal recognition of his title “Dr.” in 1873.[49] His name was subsequently included in the 1884 list of licensed physicians for Richland County, which credits him as having a diploma but conspicuously leaves blank the columns for “Date Issued” and “By Whom Granted” (fig. 20).[50]

Presumably, “Dr.” Davis continued to practice unimpeded until 1893, when he appears in a series of newspaper accounts about legal charges brought against him, this time by Adolph (sometimes Adolphus) Holuv (sometimes Hulob, Hublov, or Hohler), variously described as a “farmer,” a “German,” a “Dutchman,” and a “Hungarian” of Orangeburg, South Carolina. An article published in Orangeburg’s Times and Democrat on July 19, 1893, shows the charges to be “receiving money on false pretenses” (fig. 21). Holuv’s complaint was that after contracting with Davis to “conjure away all storms, drought, pestilences, and sickness, etc.” from his farm, the doctor had not lived up to the terms of the agreement, and by way of evidence offered that “his sister-in-law was then lying critically ill; that he had lost eighteen hogs by sickness; that his cow, which had a fine udder and looked like she would give five gallons, would only give about a quart.” He also claims that “Davis had conjured his family, stock, and crops” in retribution for Holuv’s complaints that the conjures had not worked.

Progress of the case appeared in South Carolina’s Laurens Advertiser on October 10, 1893 (fig. 22). The Holuvs are not mentioned by name but are described as a family of “Bohemians.” Dr. Davis claims to be a “veterinary surgeon and is popularly classed as a voodoo or hoodoo doctor.”[51]

In October 1893 The State described the accused as “old Peter Davis, the negro herb doctor” (fig. 23) and pointed out that “this is the third time that he has been arrested on the same charge and for the same offense.”[52] By then Davis’s case had gained considerable attention as it continued to heat up in South Carolina newspapers. The Camden Chronicle best summarizes the details of the case against Dr. Davis and is transcribed in its entirety here:

THE HOODOO DOCTOR

Trial Justice C. P. Brunson was engaged all day last Friday in the preliminary hearing of the State against “Dr.” Peter Davis, of Columbia, a cross between a gorilla and a badger and a lineal descendant of one of the witches of “Macbeth.” The charge upon which the defendant was arraigned being “voodoism.” The prosecutor was a Hungarian of the Knott’s Mill section, named Adolphus Hulob [Holuv], who testified as follows: That owing to the sickness of two of his horses, and the death of one, he consulted a neighbor as to the best course to pursue toward getting the animals well. This neighbor advised him to consult the defendant. Soon afterward he went to Columbia and called on “Dr.” Peter Davis, and asked him his advice. Deponent said by signing a contract agreeing to pay him (Davis) $55 he would give him medicines etc., that would not only cure his horses, but also keep his family and all his stock in perfect health. Hulob paid the doctor $17 for which he received roots and different kinds of medicines, which he gave his family and stock according to direction. Nine days afterward he lost 27 hogs, and his wife and sister-in-law were made very sick. At his next visit to the skillful doctor he received a loadstone for which he paid $5. This he was to put whiskey on once a week, while doing which, he was to raise one hand and open and shut the fingers thereof. The effect of which ceremony would keep away the enemy who was poisoning his horses. At one time he was presented with a gourd two feet long. He was to cut off the necks and scatter about his yard at 12 o’clock in the night the seed of the gourd. This would prove a most effectual sanitary measure for his chickens, geese, and jackasses. He was also the recipient of some loadstone powders, which after being put in the gourd and moistened, were to be rubbed on the faces of Hulob and his family, also as a sanitary measure. At his next visit to the eminent M. D. Hulob received 3 pieces of load-stone which he was to carry in his pocket for nine days, after first wetting them with a strong smelling liquid very easy to obtain. This was to neutralize malaria and make witches keep at a distance. Davis was put in jail to await trial in default of $200 bond. Orangeburg Enterprise.—[53]

Yet another retelling of the case appeared on November 15, 1893, in the Charlotte News with the incendiary title “A Dutchman Hoodooed: A Wily Negro ‘Doctor’ Pulled Up in a South Carolina Court” (fig. 24). That version included new details of the case, notably that Peter Davis had given Holuv (spelled Hohler here) “graveyard dirt” to spread on the farm, which would encourage a bumper crop of cotton. Holuv testified that he used the graveyard dirt as directed, complaining to the judge, “your honor, I plant 13 acres, and make only one bale cotton.”

Versions of the case with slightly different accounts of the testimony continued to appear in national newspapers well into 1894.[54] Somewhat anticlimactically, and in spite of all the public interest in the case, the Orangeburg Court of General Sessions indicated that the solicitor never obtained an indictment and the case was dismissed on January 8, 1894.[55] Presumably Dr. Davis continued to practice his profession.

The last public mention of Dr. Davis is his death record, which indicates he died from “Senile Exhaustion” on December 21, 1911, at the age of 99. He was buried in an unmarked plot at the so-called Colored Asylum Cemetery in Columbia, now called the South Carolina State Hospital Cemetery for African Americans.[56] The cemetery was established as a segregated burial ground exclusively for Black patients from the now-defunct State Hospital for the Mentally Ill, which operated on Bull Street from 1828 through the 1980s. Between 2,000 and 3,500 African-Americans were buried in this historic cemetery until 1922, when the hospital designated a new burying ground for Black patients on Slighs Avenue.[57]

Folk-Magic Practices and Containers

Of course one wonders how Dr. Davis’s ring bottle functioned within his practice. No direct information about the vessel is known other than the inscription on the base. Was it a special presentation piece, perhaps from a grateful client? Or was it something Dr. Davis simply ordered for himself?

I introduced this article referencing the phenomena of witchcraft and sorcery in seventeenth-century Great Britain. During that period, proscriptive texts for the preparation of so-called witch bottles as counter spells to evil are well documented. The container of choice for such protective charms was a stoneware bottle form known as a Bartmann (Ger. “bearded man”), so named for the decorative bearded face mask on its lower neck. More colloquially, it is called a Bellarmine. An example of period instructions for making these counter-magical charms comes from Joseph Glanvill (1636–1680/1) in Saducismus Triumphatus: or, Full and Plain Evidence Concerning Witches and Apparitions.[58] Instructions given to a man who thought his wife had been possessed were to fill a bottle with his wife’s urine “together with Pins and Needles and Nails,” cork it, then place it in a hearth fire.[59] Examples of such witch-bottle charms are often found buried in areas associated with hearths and chimneys (figs. 25, 26).

Archaeological specimens found in North American excavations suggest that witch bottles were being used in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and well into the twentieth century.[60] Widely available glass containers, such as wine bottles, medical bottles and phials, and ointment jars became the favored receptacle for those charms. Like their English counterparts, they were intentionally placed near hearths or doors to protect the house and ward off evil. The earliest identified example, a mid-eighteenth-century English wine bottle containing six brass pins and sealed with a wood stopper, was found near the base of a house’s chimney in Delaware County, Pennsylvania.[61]

Since the publication of that find, dozens of other glass witch bottles have been identified in archaeological deposits in America.[62] Figure 27 illustrates a fragmentary black-glass English wine bottle, also of the mid-eighteenth-century, that was recovered adjacent to a brick hearth from a mid-nineteenth- to early-twentieth-century tenant-house site in Maryland’s Dorchester County.[63] Although the bottle was broken, seven copper-alloy pins were found stuck in its cork.

The most celebrated ceramic vessels associated with spiritual or magical practices are the mysterious stoneware face vessels made by enslaved African-American potters in the Edgefield District of South Carolina in the mid-nineteenth century. Various theories suggest that they served as powerful ritual objects used in conjuring.[64] The connection between Edgefield face vessels and African-American magic is circumstantial, as the evidence comes primarily from oral histories, yet physical evidence does appear on several examples, which could shed light on their use.[65] The face jug on the left in figure 28 has traces of red pigment, possibly ocher or even brick dust, that was placed in the pupils and over the kaolin teeth at some point (fig. 29). This red pigment has a long history of use in conjure and for protection against evil.[66] The jug on the right in figure 28 has a circular hole in the bottom that might have served a supernatural function. A number of glass and ceramic vessels retrieved from African-American graves in many Southern cemeteries have been ritually “killed” by having their bottoms broken out (fig. 30).[67] John Vlach has observed that this was a practice rooted in African belief systems, based on writings by ethnologist E. J. Glave who wrote about grave decoration with “crockery, empty bottles, old cooking pots, etc., etc., all of which are rendered useless by being cracked or penetrated with holes.”[68]

In 2017 a fascinating salt-glazed ointment jar appeared in a social-media feed and was later acquired by my colleague Curtis Rice. The jar was inscribed with representations of two plants, along with a series of incised triangles and crosses on a portion of the rim (fig. 31). It was once in the collection of the late Dr. Stephen Leder, a Yale professor of medicine and a serious stoneware collector who had written on Bennington, Vermont, stoneware, but little other history is known.[69] Based on the characteristics of the clay color and the interior dark-brown clay slip, the jar was thought to have been made in or near the Valley of Virginia, perhaps around the mid-nineteenth century. Given this likely geographic origin manufacture, it was thought to have been used in immigrant Germanic folk medicine rather than Southern conjure.[70]

One of the plants was thought to be garden angelica (Angelica archangelica), and the other a type of thistle plant (fig. 32). Both plants have a long history of medicinal use.[71] Angelica is commonly used for protection against evil spirits, as well as healing.[72] It has been designated one of the “lunar herbs,” and it is possible that an incised figure on the jar’s body represents the so-called man in the moon (fig. 33).[73]

In 2018 a small stoneware flask was brought to my attention by Rick Meech Burchfield, a collector of stoneware flasks (fig. 34). Rick was asking for an opinion on the vessel’s origin. The bottle has a flattened shape and a reed neck seemingly of the early nineteenth century. Both sides are decorated in a snakelike ribbon of cobalt. More significant to me at the time was the rolled-up fragment of printed paper that had been found inside the bottle. Close examination revealed that it had been torn from a King James Version of the Bible, retaining partial verses from the book of Romans (figs. 35, 36). The Bible is often cited in hoodoo spells; in fact, many agree that it is “the greatest conjure book in the world.”[74] Harry Middleton Hyatt, among others, recorded the use of torn pages of scripture in many conjure and hoodoo spells.[75] Contemporary practitioners of “Bible Magic” discourage the tearing or defacing of Bibles, opting instead to write out by hand the specific verses on paper and using that instead.[76]

From the review of the preceding examples, it is clear that ceramics and glass vessels have a long history of use in the creation of supernatural charms and spells. But the question of how the ring bottle may actually have functioned in Dr. Davis’s Columbia, South Carolina, practice remains open to speculation and further investigation. At the very least, it probably held whiskey or another distilled spirit—always cited as the single most universal ingredient in conjure and rootwork prescriptions (fig. 37). Alternatively, it could have contained specific “waters” or potions concocted by Dr. Davis. One might imagine these liquids being ceremoniously dispensed from such an imposing container.

Like a shaman’s staff or a fortune teller’s crystal ball, the ring bottle conceivably represented a symbolic “power” object, possessing energy for protection, luck, and good intentions beyond its physical existence. The ring has symbolic meanings much like the ouroboros did for the ancient Egyptians and Greeks (fig. 38). The ouroboros represents a snake or a dragon eating its own tail and serves as a symbol for eternal cyclic renewal or a cycle of life, death, and rebirth. Psychologist Carl Jung observed that “One symbol of original perfection is the circle. Allied to it are the sphere, the egg, and the rotundum—the ‘round’ of alchemy.”[77]

The ring bottle's contents have remained undisturbed, sealed with a cork. X-ray analysis might prove fruitful for deciding the next step in the investigation. I have spoken with several conservators about determining its contents, but I have been advised by more than one person of the potential adverse reaction if the bottle is unsealed. Jack Montgomery, who grew up in Columbia and has studied and written on magical healing, was particularly excited about the find but cautioned: “sounds like you might have a ‘trap.’ Enjoy it, but do be careful. Sounds like that root-doctor was quite accomplished.”[78]

Imagining Dr. Davis

No visual record of Dr. Davis has yet been discovered. From newspaper descriptions we have a few disparaging comments, such as “a cross between a gorilla and a badger,” which are consistent with historical accounts citing distinctive physical characteristics that set both male and female conjurers and rootworkers apart from others. This phenomenon is seen in other cultures where shamans are often those who have physical abnormalities that signify a person who might have a special relationship with the spirit world. As Newbell Niles Puckett has commented: “In Africa, the witch-doctor is usually selected because of some physical or mental peculiarity which shows him to be possessed of a spirit. I have noticed that the American witch-doctor is also possessed of unusual mentality and often shows physical peculiarities as well.”[79]

An early visual rendering of an American hoodoo doctor is found in Mary Alicia Owen’s chapter “Luck Balls,” in which she describes her interactions with “King Alex—a Voodoo doctor or cunjurer of great powers and influence.”[80] The illustration of King Alex shows him “charging” a mojo bag, or luck ball, with a dose of “Old Rye,” a process that Owen witnessed firsthand (fig. 39). Her description of his physical appearance is matched only by the rendering, which serves as the frontispiece for the chapter as well as the book:

His eyes were snaky, his narrow forehead full at the eyebrows but shockingly depressed above. His nose was broad and with a flatness of nostrils emphasized to the perception of the beholder by the high, bony ridge that divided them. His chin was narrow and prominent; at first glance, it seemed broad by reason of the many baggy folds that surrounded it after the fashion of a dew-lap. He was far from beautiful when his features were in repose, but the time to fully realise that he was a self-chosen disciple of his Satanic Majesty was when he unclosed his great rolling lips in a silent laugh.[81]

In 1898 Leslie’s Weekly published “Fortune Teller Reading the Palm of a Society Lady,” a large, two-page spread showing a Black woman in front of her hearth reading the palm of a white female client (fig. 40).[82] By the early twentieth century, the telling of fortunes was an important part of conjuring, which included white professional fortune tellers catering to privileged clientele throughout America.[83] The photograph is particularly valuable, however, for the wealth of material culture in the scene, including what appear to be herbs and a so-called memory jug on the hearth.[84]

Several compilations of photographs of male and female root doctors can be found in published works and online repositories.[85] Most important is the image collection by folklorist Newbell Niles Puckett, who photographed African-American conjure doctors in his native Mississippi and South Carolina as part of his research (fig. 41).[86] Included in this archive, which is maintained by the Cleveland Public Library, are images of his sources and various paraphernalia associated with conjuring, such as mojo bags, charms, amulets, and “magical” plant material (fig. 42).

In the absence of a visual image of Dr. Davis, I invited New Orleans artist Andrew Hopkins to create an imagined portrait incorporating the ring bottle in the scene.[87] Andrew is well known for his interest in the creole cultures of southern Louisiana, particularly the architecture and interior furnishings of the late-eighteenth- and nineteenth-century domestic environments of New Orleans. He has made many portraits of Marie Laveau (1801–1881), who is the most famous voodoo priestess in all of America.

I provided Andrew with what background information I had at the time on Dr. Davis, but with very little instruction, leaving the end result up to his artistic vision. The resulting portrait offers a respectful rendering of the man, dressed in a formal suit with a pleated shirt, cravat, and vest (fig. 43). He is seated at a cloth-covered table, the stoneware ring bottle in the foreground painted to scale, with some herbs and a pile of powder, perhaps graveyard dirt or a concoction of salts. In his hand, he holds a root.

In homage to the deep-seated connections of Black American root-workers, Andrew created a companion portrait of Marie Laveau (fig. 44).[88] Her appearance is based on a ca. 1837 oil painting that depicts a New Orleans free woman (identified by the tignon she wears, which was legally mandated to identify free women of color) who supposedly is Marie Laveau.[89] Much has been written about her life and her exploits, though most of it highly sensationalized fictional accounts.[90] Despite the legends of her wild voodoo ceremonies and malevolent behavior, she was a devout Catholic who ministered to the sick and poor. She is depicted in Andrew’s portrait wearing a tignon and holding a rosary made of white beads.[91]

Re-creating Dr. Davis’s Medical Bag

In her 1935 collection of Southern Negro folktales, Mules and Men, Zora Neale Hurston included an appendix of “Paraphernalia of Conjure.” Even though thirty-eight lengthy entries of various oils, powders, candles, medals, and natural herbs, roots and other materials are given as examples, Hurston concedes: “It would be impossible for anyone to find out all the things that are being used in conjure in America. Anything may be conjure[,] nothing may be conjure, according to the doctor, the time[,] and use of the article.”[92]

My initial plan was to re-create the specifics of Dr. Davis’s “medical cabinet” from the various newspapers between 1893 and 1894 which listed a number of common hoodoo substances. I developed what might be described as a shopping list of the paraphernalia and ingredients cited. The list includes:

HOODOO WATER. These waters are prescribed for protection, cleansing, and blessing. These waters go by various names include Florida Water, Floor Wash, Moon Water, Indigo Water, and War Water.

GRAVEYARD DIRT. One of the essential ingredients in hoodoo and rootwork is the soil taken from the burial shaft of a human grave. Used in rituals and spells, graveyard dirt conveys the powers of the dead over the living.

DEADMEN'S POWDER. Most often referred to as “goofer dust,” this powder can contain a mixture of graveyard dirt with salt, cayenne or black pepper, gunpowder, sulfur, ground bones, and anvil dust (fig. 45).

LODESTONES. Used for centuries in magic, lodestones are natural magnets that “charge” spell items and “power” mojo bags and gris gris bags. They are said to attract good luck, healing, and more.

WHISKEY. Whiskey, or sometimes rum, is used in conjunction with many other ingredients to activate the power of a charm. Mojo bags are routinely feed offerings with whiskey.

GOURDS. These inedible, hard-rinded fruits are often used as containers for various conjure ingredients such as roots, graveyard dirt, and powders, that might otherwise be found in a mojo or conjure bag.

ROOTS. Many common culinary and medicinal herbs are used in rootwork, conjure, hoodoo, and other healing practices, among them mint, jimson weed, sassafras, various peppers, and milkweed, as well as strange-sounding roots such as High John the Conqueror, five-finger grass, and devil’s shoestring (catgut).[93]

I had wanted to visit the Columbia area to see what I could purchase from the half dozen modern-day emporiums categorized as spiritual, occult, herb, holistic healing, or metaphysical supply stores. With fitting names like Belladonnas, Seven Rays Book Store, Rose Marie Spiritual Gifted Reader & Advisor, Sphinx Paw, Solomon’s Temple, and St. Francis Catholic Shop, these businesses are located today within just a few miles of where Dr. Davis had lived and worked.[94] Due to travel issues related to the Covid-19 pandemic, I turned to what most of us had done during that time of restricted personal contact and explored my online options. Amazingly, within a half hour or less of electronic browsing through eBay, Etsy, and Amazon, plus the magic of second-day shipping, I was able to replicate key components of Dr. Davis’s medicine cabinet (fig. 46). Remarkably, these ingredients and the recipes for their use appear to have remained unchanged since the late nineteenth century, when written accounts were first compiled.

Concluding Thoughts

When a newspaper correspondent in November 1893 characterized Dr. Davis as a “lineal descendant of one of the witches of ‘Macbeth,’” the writer was acknowledging the universal belief in the invocation of supernatural powers to craft changes in the human condition through the intercession of magic.[95] Unlike Shakespeare’s dramatis personae of the Three Witches, Peter Davis was not a fictional creation. He lived, breathed, and practiced folk magic in nineteenth-century Columbia, South Carolina. Rather than using the witches’ ingredients of “eye of newt” and “toe of frog,” Dr. Davis relied on “graveyard dirt” and “dead men’s powder” for his conjurations.

While we are limited in our knowledge of the full range of Dr. Davis’s skills, we can surmise that his clients/patients sought out the typical hoodoo cures for illnesses, charms for protection and good luck, and perhaps fortune telling. The ethnic identity of Davis’s disgruntled client Adolph Holuv as “German,” a “Dutchman,” and a “Hungarian” corroborates Jack Montgomery’s study of South Carolina’s folk healers which suggests that German-speaking settlers, in the so-called Dutch Folk area of the Columbia area, were predisposed to powwow and other magical alternatives.[96] His observations imply that those practices overlapped in the African-American and Germanic communities; hence, Dr. Davis’s services would have been a natural outreach for Holuv.

Among the most widely documented services of nineteenth-century hoodoo doctors were intercessions for successful outcomes in legal proceedings and court cases. We know that Dr. Davis interacted with the court system on several occasions both as a plaintiff and as a defendant. As Jeffrey Anderson observed, during the Jim Crow era “African-Americans required all the legal help they could get,” and the hoodoo doctor provided those who believed in magic with spells to sway judges, juries, and law-enforcement officials.[97] Other writers go so far as to proclaim that hoodoo doctors were considered the poor man’s lawyers in the Black communities that were denied professional legal services (figs. 47, 48).[98] Readers may recall the scenes in John Berendt’s 1994 novel (and its subsequent 1997 film) Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, in which the Savannah, Georgia, root doctor Minerva chews the root and employs graveyard dirt in her spells during the murder trial of antiques dealer Jim Williams, seeking a favorable outcome.[99]

Perhaps like many readers, my feelings about hoodoo were conditioned somewhat by stereotypes that developed from exposure to gothic novels, visiting tourist voodoo shops on Bourbon Street, and watching Hollywood horror films. In most cases, those sources left the impression that hoodoo was primarily intended as “black magic” for curses and nefarious outcomes. Other perceptions of hoodoo were, and still are, associated with fraudulent scams, with psychic ‘healers’ simply taking money from unsuspecting clients. Nineteenth- and twentieth-century newspapers are replete with tales of gullible “clients” giving their hard-earned money to fortune tellers, root doctors, and spiritual advisers.[100] And while there is no question that an exploitative component exists in many transactions, “real” hoodoo is intended to promote the well-being of a person’s spiritual and physical life.

After emancipation, thousands of male and female rootworkers in African-American communities in the South and the North were active in the “old tradition black belt Hoodoo.”[101] Using herbs, roots, minerals, and other natural resources, the rootworker was an alternative for those denied access to formal medical care or who simply did not trust the system. In the twentieth century the practice was codified in the music of the American blues, although many today who sing along to the “Hoodoo Man” song have only a vague understanding of the historical depth and significance of its lyrics. An active commercial market for hoodoo supplies developed, targeting African-American consumers throughout the country. Today, hoodoo doctors offer advice, counsel, and spiritual interventions to their clients using Instagram and Facebook, and can be paid via PayPal.

Although countless men and women were engaged in conjuring and rootwork within their respective communities, most remained nameless. By virtue of the widespread newspaper reporting of his legal woes in 1893, Dr. Davis may represent one of the most recognized hoodoo doctors of his time. Furthermore, no other nineteenth-century object, and certainly no ceramic vessel, has ever had such firm association with a specific hoodoo doctor. For example, despite the notoriety of New Orleans’s Marie Laveau, no artifacts associated with her life have been identified.

The Peter Davis stoneware ring bottle provides a physical and tangible link to an under-interpreted practice of African-American folk magic that was part of Southern culture from the early days of colonization and slavery and continues into the present day. It is an object with great symbolic power and it possesses a remarkable tactical quality, and almost magnetic resonance, when handled in person. With a little imagination, it can transport you into an enigmatic realm of mystery and intrigue. It is one of the most important Southern ceramic artifacts to come to light in recent history.

After opening this article with some lines from the most oft-quoted magical instructions in Western literary history, I would like to conclude with one that is not as well-known but certainly would have been in Dr. Davis’s grimoire as a countercharm against conjuration. Published in 1899 in The Southern Workman and Hampton School Record, it may prove useful to readers in the unfortunate position of having had someone place an ill-intention spell on you (fig. 49).

Remedies to Cure Conjuration.

If the pain is in your limbs, make a tea or bath of red pepper, into which put salt, and silver money. Rub freely, and the pain will leave you. If sick other-wise, you will have to get a root doctor, and he will boil roots, the names of which he knows, and silver, together, and the patient must drink freely of this, and he or she will get well. The king root of the forest is called “High John, the Conqueror.” All believers in conjuring quake when they see a bit of it in the hand of anyone.[102]

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am very grateful to a number of people who facilitated the research into the history and significance of the Dr. Davis ring bottle. Thanks to Phil Wingard and the late Frank Williamson for making the acquisition of the bottle possible. Jon Prown, director of the Chipstone Foundation, subsequently acquired this important object for the collection in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Dr. Corbett Toussaint was the first to recognize the identity of Dr. Davis and provided newspaper references to the history of his practice in Columbia. April Hynes undertook courthouse research and provided copies of documents related to Dr. Davis’s legal proceedings. Luke Beckerdite contributed his insights into Obeah and provided the oil portrait of the Jamaican Obeah man. Carl Steen and Saddler Taylor made available fragments of ring bottles from the Stork pottery in Columbia. Dr. Bernard Means undertook scanning of the bottle and created 3-D replicas at Virginia Commonwealth University’s Virtual Curation Labatory. Michelle Erickson reproduced several examples of the ring bottle, using a number of iron-rich glaze formulas to better understand the technical aspects of its manufacture. The glazes were created using anvil dust provided by Ken Schwarz and Stephen Mankowski of Colonial Williamsburg’s blacksmith shop. Dr. Jane Przybysz, director of the McKissick Museum in Columbia, South Carolina, facilitated some important last-minute research with records at the South Carolina Department of Archives & History. Patricia Samford and Rebecca J. Morehouse of the Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab provided photographs and information about the glass witch bottle found in Dorchester, Maryland. Rick Meech Burchfield shared the discovery of his stoneware flask containing the remnants of a “Bible Spell.” Curtis Rice was instrumental in the acquisition of the stoneware ointment jar. Angelika Kuettner assisted with locating some important images for the article. I owe a special thanks to New Orleans artist Andrew Hopkins, who was willing to undertake the imagined portrait of Dr. Davis and the companion rendering of Marie Laveau.

William Shakespeare, Macbeth, act 4, scene 1 (Ware, Eng.: Wordsworth Classics, 1992), p. 75.

Dæmonologie, in forme of a dialogue, divided into three Bookes, https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/king-james-vi-and-is-demonology-1597.

Shakespeare, Macbeth, p. 75.

Bessie Brown, Hoodoo Blues, July 3, 1924.

Sale, October 10, 2017, Ballentine Auction and Estate Services, Columbia, South Carolina.

“A Dutchman Hoodooed,” Honolulu Advertiser, January 13, 1894, p. 2.

Trudier Harris, “Conjuring,” in The Companion to Southern Literature: Themes, Genres, Places, People, Movements, and Motifs, edited by Joseph M. Flora, Lucinda H. Mackethan, (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press 2002), pp. 182–84.

Trudier Harris, “Voodoo,” in Companion to Southern Literature, pp. 948–49.

Joseph John Williams, “Origin of Obeah,” Voodoos and Obeahs: Phases of West Indian Witchcraft (New York: Dial Press, 1932), pp. 108–41; Nathaniel Samuel Murrell, Obeah: Magical Art of Resistance in Afro-Caribbean Religions: An Introduction to Their Historical, Cultural, and Sacred Traditions (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010), p. 231.

Blake Touchstone, “Voodoo in New Orleans.” Louisiana History 13, no. 4 (1972): 371–86.

Jack Montgomery, American Shamans: Journeys with Traditional Healers (Hector, N.Y.: Busca, 2008).

Walter Rucker, “Conjure, Magic, and Power: The Influence of Afro-Atlantic Religious Practices on Slave Resistance and Rebellion,” Journal of Black Studies 32, no. 1 (September 2001): 84–103.

Christopher S. Lewis, “Conjure Women, Root Men, and Normative Visions of Freedom in Antebellum Slave Narratives,” Arizona Quarterly 74, no. 2 (2018): 113–41.

John W. Blassingame, The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South, rev. and enl. ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979), p. 110.

Henry Bibb, Narrative of the Life and Adventures of Henry Bibb: An American Slave (New York: Published by the author, 1849), p. 12, available online at https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/bibb/bibb.html.

William Wells Brown, My Southern Home: or, The South and Its People (Boston: A. G. Brown & Co., 1880), p. 70.

Alicia M. Simmons, “The Power of Hoodoo: African Relic Symbolism in Amistad and The Narrative of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave,” Oswald Review 2, no. 1 (2000): 41–47, available online at https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/tor/vol2/iss1/5.

Frederick Douglass, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Written by Himself (Boston: De Wolfe & Fiske Co., 1892), pp. 170–71.

Glenda Sullivan, “Plantation Medicine and Health Care in the Old South,” Legacy 10, no. 1 (2010): 17–35, available online at http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/legacy/vol10/iss1/3; Michele Elizabeth Lee, Working the Roots: Over 400 Years of Traditional African American Healing (Oakland, Calif.: Wadastick Publishers, 2015); Sharla M. Fett, Working Cures: Healing, Health, and Power on Southern Slave Plantations (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002).

In Herbert C. Covey, African American Slave Medicine: Herbal and Non-Herbal Treatments (Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2007); David McBride, “ ‘Slavery as It Is’ : Medicine and Slaves of the Plantation South,” OAH Magazine of History 19, no. 5, Medicine and History (September 2005): 36–39; Jerome S. Handler, Slave Medicine and Obeah in Barbados, Circa 1650 to 1834 (Netherlands: KITLV Press, 2000) [originally published in New West Indian Guide/Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 74, no. 1/2 (2000): 57–90].

Fett, Working Cures, p. 36.

Katrina Hazzard-Donald, “Crisis at the Crossroads: Sustaining and Transforming Hoodoo’s Black Belt Tradition from Emancipation to World War II,” Mojo Workin’: The Old African American Hoodoo System (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2022), pp. 84–115.

Memphis (Tenn.) Daily Appeal, October 25, 1868, p. 3.

Catherine Yronwode, “Source Materials on Hoodoo, Rootwork, and Conjure: African-American Folk Magic and Spirituality” (Yronwode Institution for the Preservation and Popularization of Indigenous Ethnomagicology, 2019), http://www.yronwode.org/hoodoo-bibliography.html; Alice M. Bacon, “Folk-Lore and Ethnology: Conjuring and Conjure Doctors,” Southern Workman 24, no. 11 (November 1895): 193–94.

Anonymous Hampton student or student-teacher, “Folk-Tales and Conjure,” Southern Workman and Hampton School Record 28 (March 1899): 112–13.

Mary Alicia Owen, Old Rabbit, the Voodoo, and Other Sorcerers, illustrated by Juliette A. Owen and Louis Wain (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1893).

Biographical information for Mary Alicia Owen can be found at https://historicmissourians.shsmo.org/mary-alicia-owen.

“James Ellis, (Dock) the white hoodoo doctor and preacher has been arrested and is in Spartanburg jail, charged with rape,” The Gaffney (S.C.) Ledger, September 12, 1899, p. 2.

Jeffrey E. Anderson, Hoodoo, Voodoo, and Conjure (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 2005), pp. 93–96.

“Mississippi Hoodoo Doctor,” in Photographs from the Puckett Collection: Folk Beliefs of African Americans in the Southern United States, Cleveland Public Library, https://cplorg.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4014coll9/id/37/rec/7.

Wendy Dutton, “The Problem of Invisibility: Voodoo and Zora Neale Hurston,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 13, no. 2 (1993): 131–52.

Zora Hurston, “Hoodoo in America,” Journal of American Folklore 44, no. 174 (October–December 1931): 317–417.

Harry Middleton Hyatt, Hoodoo –Conjuration –Witchcraft –Rootwork; Beliefs Accepted by Many Negroes and White Persons, These Being Orally Recorded among Blacks and Whites, 5 vols. (Hannibal, Mo.: Western Publishing, 1970).

Michael Edward Bell, “Harry Middleton Hyatt’s Quest for the Essence of Human Spirit,” Journal of the Folklore Institute 16, no. 1/2 (1979): 1–27.

Hyatt, Hoodoo –Conjuration –Witchcraft –Rootwork, 3:xv.

Yvonne Chireau, “Conjure Magic and Supernaturalism in Nineteenth-Century African American Narratives,” in Voodoo, Hoodoo and Conjure in American Literature: Critical Essays, edited by James S. Mellis (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co., 2019).

Laurie A. Wilkie, “Secret and Sacred: Contextualizing the Artifacts of African-American Magic and Religion,” Historical Archaeology 31, no. 4 (1997): 81–106; Aaron E. Russell, “Material Culture and African-American Spirituality at the Hermitage,” Historical Archaeology 31, no. 2 (1997): 63–80; Christopher C. Fennell, “Conjuring Boundaries: Inferring Past Identities from Religious Artifacts,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 4, no. 4 (2000): 281–313; S. K. Moses, “Enslaved African Conjure and Ritual Deposits on the Hume Plantation, South Carolina,” North American Archaeologist 39, no. 2 (2018): 131–64.

Denise Alvarado, Voodoo Hoodoo Spellbook (San Francisco: Weiser Books, 2011); Hoodoo Sen Moise, Working Conjure: A Guide to Hoodoo Folk Magic (San Franciso: Weiser Books, 2018).

Catherine Yronwode, Hoodoo Herb and Root Magic: A Materia Magica of African-American Conjure (Forestville, Calif.: Lucky Mojo Co., 2002).

John A. Burrison, Brothers in Clay: The Story of Georgia Folk Pottery (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1983), pp. 58–62.

Cinda K. Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar: Traditional Stoneware of South Carolina (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993), p. 46.

I thank Carl Steen and Phil Wingard for making me aware of these fragments.

Baldwin, Great and Noble Jar, p. 119, citing notes from an interview with R. M. Stork on file at the Charleston Museum, South Carolina.

Burrison, Brothers in Clay, pp. 172–73.

Federal Census, Inhabitants in Columbia Lower Sub Division in the County of Richland, S.C., June 14, 1880.

“Slavery at South Carolina College, 1801–1865: The Foundations of the University of South Carolina” (https://web.archive.org/web/20140722215524/http://slaveryatusc.weebly.com/urban-slavery-in-columbia.html).

His voter attestation in 1882 lists him as “Dr. Peter Davis,” a resident of Columbia’s Ward 3. Stolbrand vs. Aiken, Papers and Testimony in the Contested Election Case of C. J. Stolbrand vs. D. Wyatt Aiken, from the Third Congressional District of South Carolina, printed January 10, 1882, p. 34 (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1882). Available online at https://archive.org/details/unitedstatescon756offigoog/page/n46/mode/2up.

George Brown Tindall, South Carolina Negroes 1977–1900 (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2003).

“Peter Davis, M.D., Colored.; He Sustains His Right to the Title in Open Court,” New York Times, August 3, 1884, p. 7.

Judgment, July 15, 1884, Ledger, August 5th, 1884, Book “D”, p. 77, Richland County Court of Common Pleas.

Laurens (S.C.) Advertiser, October 10, 1893, p. 4.

“Peter Davis Re-arrested,” The State (Columbia, S.C.), October 25, 1893, p. 8.

“The Hoodoo Doctor,” Camden (S.C.) Chronicle, November 10, 1893, p.1.

The Charlotte (N.C.) News, November 15, 1893.

Orangeburg County Court of General Sessions, Journal L3806S, 1890–95, pp. S93, 595, January 8, 1894, 275K0I.

South Carolina State Hospital Cemetery Survey Index, Walker Local and Family History Center, Richland County Public Library, p. 51 (https://localhistory.richlandlibrary.com/digital/collection/p16817coll12/id/64).

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/120905946/peter-davis. Michael Trinkley and Debi Hacker, “Dealing with Death: The Use and Loss of Cemeteries by the S.C. State Hospital in Columbia, South Carolina” (Columbia, S.C.: Chicora Foundation, Inc.), January 17, 2001 (https://www.historiccolumbia.org/tour-locations/2091-slighs-avenue).

Joseph Glanvill, Saducismus Triumphatus: OR, Full and Plain EVIDENCE Concerning WITCHES AND APPARITIONS. In TWO PARTS.

The First treating of their POSSIBILITY, The Second of their Real EXISTENCE. By late Chaplain in Ordinary to his Majesty, and Fellow of the Royal Society. With a Letter of Dr. HENRY MORE on the same Subject.

And an Authentick, but wonderful story of certain Swedish Witches; done into English by Anth. Horneck Preacher at the Savoy.

LONDON: Printed for J. Collins at his Shop under the Temple-Church, and S. Lownds at his Shop by the Savoy-gate, 1681. https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A42824.0001.001?view=toc

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A42824.0001.001?rgn=main;view=fulltext.

Henry M. Miller, “Buried Bottles” (https://www.hsmcdigshistory.org/clues-to-early-maryland-8-buried-bottles/).

Marshall J. Becker, “An American Witch Bottle,” Archaeology 33, no. 2 (1980): 18–23.

M. Chris Manning,“The Material Culture of Ritual Concealments in the United States,” Historical Archaeology 48, no. 3: Manifestations of Magic: The Archaeology and Material Culture of Folk Religion (2014): 52–83.

Rebecca Morehouse, “Witch Bottle,” Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory, Curator’s Choice 2009 (Maryland Department of Planning, Jefferson Patterson Park & Museum, August 2009), https://jefpat.maryland.gov/Pages/mac-lab/curators-choice/2009-curators-choice/2009-08-witch-bottle.aspx; Martha J. Schiek and Edward C. Goodley, “Archaeological Site Examination: 18DO129, Dorchester County, Maryland” (Newark, Del.: Mid-Atlantic Archaeological Research, Inc., 1984); Rebecca Morehouse, “Witch Bottles and Bottle Charms,” The Magic and Mystery of Maryland Archaeology, Maryland Archaeology Month, Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory (April 2019), p. 6. http://marylandarcheology.org/MAM2019/2019_MAM%20Booklet.pdf, p.6.

See Regenia Alfreda Perry, Spirits or Satire: African-American Face Vessels of the 19th Century, exh. cat., Gibbes Art Gallery, Charleston (Charleston, S.C.: Carolina Art Association, 1985), pp. 7–10; Claudia A. Mooney, April L. Hynes, and Mark M. Newell, “African-American Face Vessels: History and Ritual in 19th-Century Edgefield,” Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2013), pp. 2–37.

Two other nineteenth-century Edgefield face vessels recently surfaced with histories of ownership by the family of Mrs. Mamie DeVeaux (1906–1983), a successful root doctor from Savannah, Ga. It is thought that those face vessels descended through her father, a nineteenth-century doctor. See “Voodoo Slave-Made Edgefield Face Jug Smiles for $72,000 at Slotin,” November 13, 2017, https://www.antiquesandthearts.com/voodoo-slave-made-edgefield-face-jug-smiles-for-72000-at-slotin/.

“Documenting Southern Indigenous & African-based Cultural Traditions in the 21st Century,” Hoodoo & Conjure Magazine (December 22, 2010), https://conjureartquarterly.wordpress.com/2010/12/22/find-us-on-facebook/.

John M. Vlach, The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts (Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland Museum of Art, 1978), pp. 139–47. Vlach noted that the objects found on graves included not only pottery, but also “cups, saucers, bowls, clocks, salt and pepper shakers, medicine bottles, spoons, pitchers, oyster shells, conch shells, white pebbles, toys, doll heads, bric-a-brac statues, lightbulbs, tureens, flashlights, soap dishes, false teeth, syrup jugs, spectacles, cigar boxes, piggy banks, gun locks, razors, knives, tomato cans, flower pots, marbles, bits of plaster, [and] toilet tanks.”

Ibid., p. 142, citing E. J. Glave, “Fetishism in Congo Land,” Century Magazine 41 (1891): 825.

Steven B. Leder and Fred Cesana, The Birds of Bennington (Hamden, Conn.: Stoneware Publications, 1991).

Robert Phoenix, The Powwow Grimoire (Lemoyne, Pa.: self-published, 2017).

David L. Cowen, “The Folk Medicine of the Pennsylvania Dutch Pharmacy in History,” American Institute of the History of Pharmacy 55, no. 2/3 (2013): 88–95.

Yronwode, Hoodoo Herb and Root Magic, p. 30.

Aurora Kane, Moon Magic: A Handbook of Lunar Cycles, Lore, and Mystical Energies (New York: Quarto Publishing, 2020), pp. 50–55.

Hurston, Mules and Men, p. 287; Anderson, Hoodoo, Voodoo, and Conjure, pp. 4–5; Theophus H. Smith, Conjuring Culture: Biblical Formations of Black America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), p. 32.

Hyatt, Hoodoo –Conjuration –Witchcraft –Rootwork, 5:4051, entry 10708. Hyatt records several “spells” that make use of torn Bible verses; one informant from Fayetteville, North Carolina, prescribed the following for success in job hunting: “Tear Leaf From Bible—In It Wrap Up Salt And Red Pepper—Pray Over—Boss Likely To Give Job.” Ibid.

Miss Michaele and Professor Charles Porterfield, Hoodoo Bible Magic: Sacred Secrets of Scriptural Sorcery (Forestville, Calif.: Missionary Independent Spiritual Church, 2014), p. 21.

Carl Jung, The Origins and History of Consciousness (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1973), p. 8.

Personal communication via Internet, January 23, 2018; Montgomery, American Shamans.

Puckett, Folk Beliefs of the Southern Negro, p. 201.

Owen, Old Rabbit, The Voodoo, p. 173.

Ibid.

“The Blackville Gallery, — No. IV,” Leslie’s Weekly, January 20, 1898, pp. 40–41.

Henry Carrington Bolton, “Fortune-Telling in America To-Day. A Study of Advertisements,” Journal of American Folklore 8, no. 31 (October–December 1895): 99–307.

The interior, which might have been staged for photographic effect, is very similar to the oil paintings of Harry Herman Rosewell (ca. 1867–1950), an American genre artist who made a series of portraits of African-American fortune tellers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. See Rena Tobey, “Harry Roseland: Reading Tea Leaves,” July 2, 2013, New Britain Museum of Art (https://nbmaa.wordpress.com/2013/07/02/harry-roseland--reading-tea-leaves/).

See online images Denise Alvarado, “Conjure Doctors & Spiritual Mothers,” https://www.conjuredoctors.com/conjure-doctors.html; and Tony Kail, A Secret History of Memphis Hoodoo: Rootworkers, Conjurers, and Spirituals (Charleston, S.C.: History Press, 2017).

https://cplorg.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p4014coll9/id/19.