Ring bottle, attributed to Edward and Robert Stork Pottery, Columbia, South Carolina, 1888. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10". (Chipstone Foundation; all photos by Robert Hunter unless otherwise noted.) The hollow ring that forms the body was thrown on the wheel from a single ball of clay. The neck/mouth was thrown in a separate operation. The solid rectangular base was molded by hand. These components were assembled at the leather-hard state of the clay. The handle was pulled separately and attached to the body.

Inscription on the base of the ring bottle illustrated in fig. 1: “Dr. Peter / Davis / 1888”

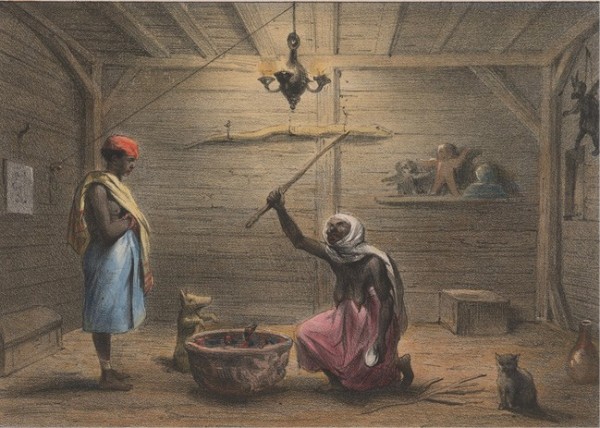

Jean-Baptiste Madou (1796–1877) and Pierre Jacques Benoit (1782–1854), La Mama-snekie, ou water-mama, faisant ses conjurations (1839), p. 36. Voyage a Surinam: Description des possessions Néerlandaises dans la Guyane (Brussels: Société des Beaux-Arts, 1839). Colored lithograph on paper. 8 1/4"x 11 3/8". (John Carter Brown Library, Brown University.)

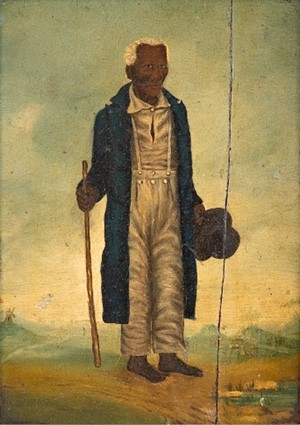

Unknown artist, Obeah Man, probably Jamaica or Barbados, ca. 1830. Oil on mahogany panel. 7 1/4"x 5 1/4". (Private collection.)

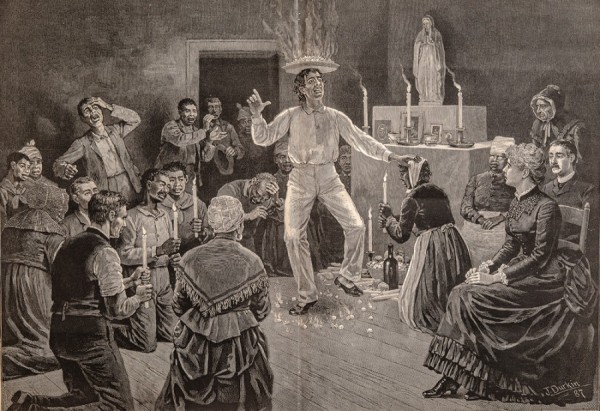

“A Voudoo Dance,” drawn by John Durkin, Harper’s Weekly, June 25, 1887, pp. 456–57. Uncolored engraving. 16 x 22". (Private collection.)

Book cover, Old Rabbit, the Voodoo, and Other Sorcerers by Mary Alicia Owen, illustrated by Juliette A. Owen and Louis Wain (London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1893).

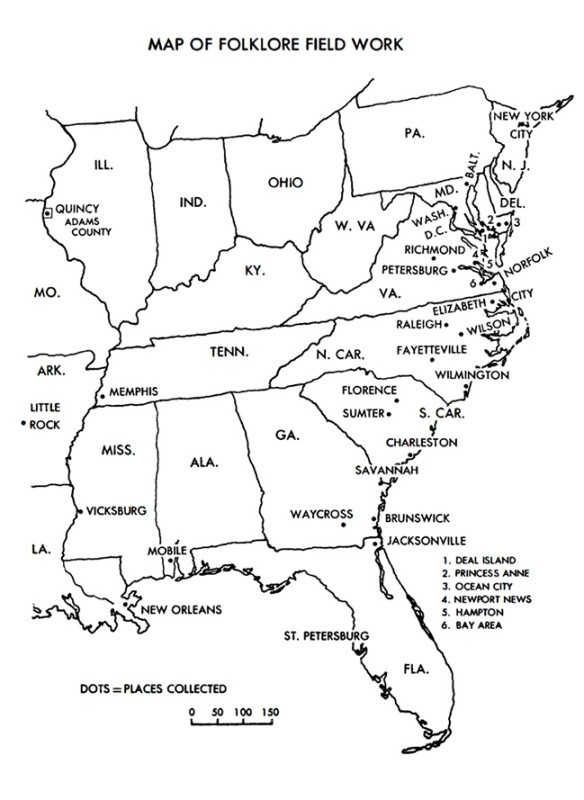

“Map of Folklore Field Work,” from Harry Middleton Hyatt, Hoodoo—Conjuration—Witchcraft—Rootwork: Beliefs Accepted by Many Negroes and White Persons, These Being Orally Recorded among Blacks and Whites, Memoirs of the Alma Egan Hyatt Foundation 5: frontispiece ([Hannibal, Mo.]: Printed by Western Pub., 1978).

Ring flask, Cypro-Geometric III–Cypro-Archaic I, 850–600 b.c. Terracotta. H. 6 3/4". (Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cesnola Collection, Purchased by subscription, 1874–76, 74.51.651.)

Ring bottle, New York, New York, ca. 1800–1830. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/2". (New-York Historical Society, Purchased from Elie Nadelman, 1937.579.)It is decorated with incised hearts, fish, birds, and the initials “M.S.”

Ring bottle, attributed to the Landrum Pottery, Richland County, South Carolina, ca. 1870. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/8". (Chipstone Foundation.)

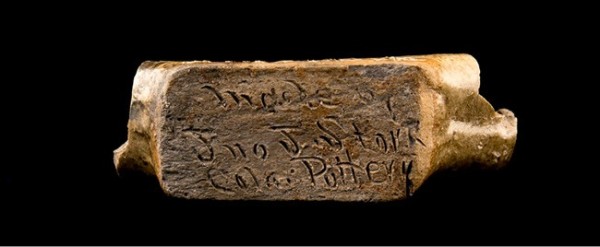

Archaeological fragment of ring bottle, John Stork Pottery, Columbia, South Carolina, ca. 1880. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. Inscribed on ring, “John J. Stork” (Courtesy, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology.)

Detail showing the base of the ring bottle fragment illustrated in fig. 11. Inscribed “made by / Jno J. Stork / Col. Pottery”

Detail showing the dark, iron-rich glaze of the ring bottle illustrated in fig. 1.

Ring bottle, Edward L. Stork, Orange, Georgia, ca. 1909. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/2". Impressed: “E.L. STORK / ORANGE, GA.” (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation.)

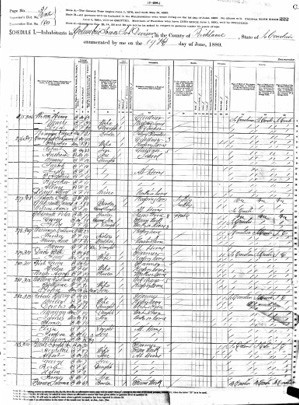

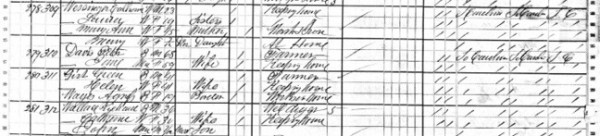

1880 Federal Census, “Inhabitants in Columbia Lower Sub Division in the County of Richland, State of South Carolina, June 14, 1880.”

1880 Federal Census entry for Peter Davis as a Black male, age 68, occupation farmer, and listing his birthplace and that of his parents as South Carolina.

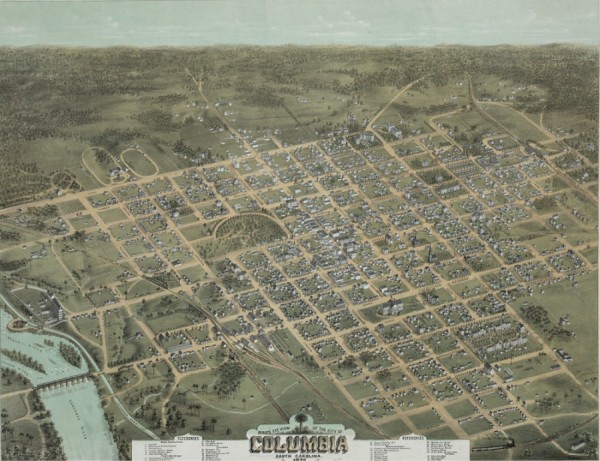

C. N. Drie, Bird’s Eye View of the City of Columbia, South Carolina (Baltimore, Md., 1872). Colored lithograph on paper. 21 1/4x 27 1/2". (Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C., 2008675451.)

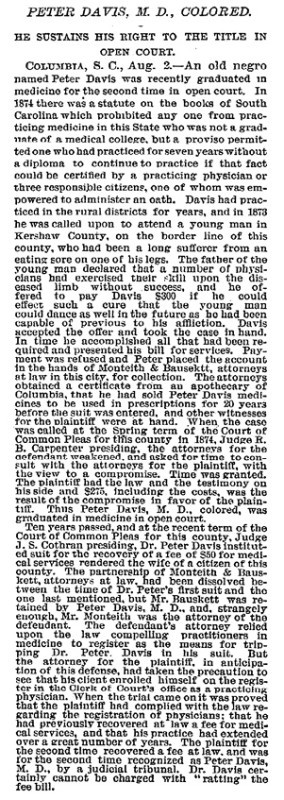

“Peter Davis, M.D., Colored. He Sustains His Right to the Title in Open Court,” New York Times, August 3, 1884, p. 7.

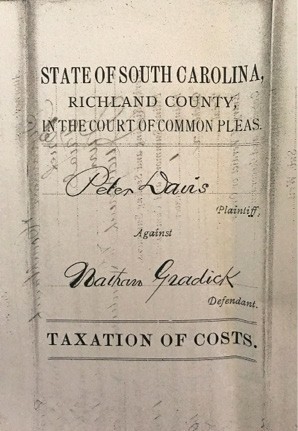

Peter Davis vs. Nathan Gradick, Taxation of Costs, State of South Carolina, Richland County, in the Court of Common Pleas, July 21, 1884.

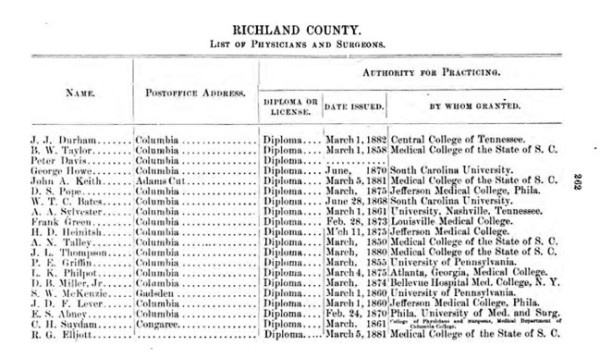

“List of Licensed Physicians and Surgeons of the State” (Richland County, South Carolina), Reports and Resolutions of the General Assembly of South Carolina, at the Regular Session Commencing November 23, 1886, Vol. 2 (Columbia, S.C.: Charles A. Calvo Jr., State Printer, 1887), p. 262. Available online at https://www.carolana.com/SC/Legislators/Documents/.

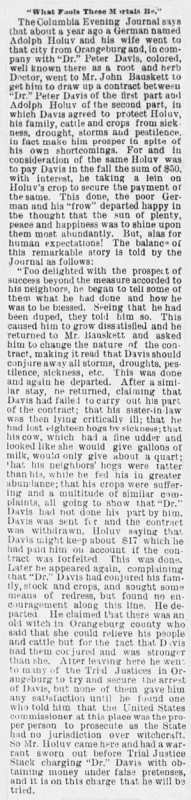

“What Fools These Mortals Be,” The Times and Democrat (Orangeburg, S.C.), July 19, 1893, p. 8.

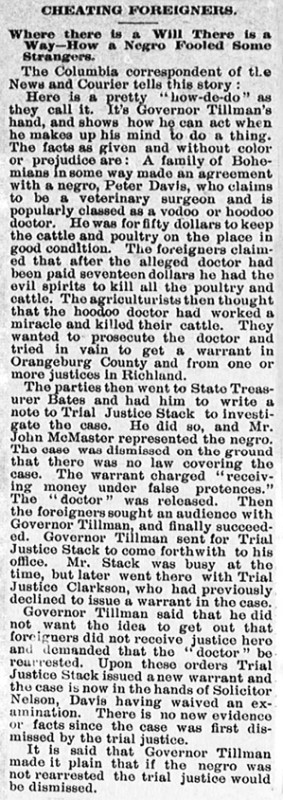

“Cheating Foreigners,” The Laurens (S.C.) Advertiser, October 10, 1893, p. 4.

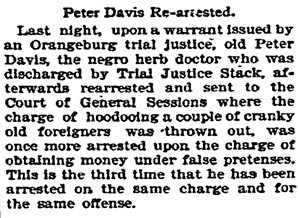

“Peter Davis Re-arrested,” The State (Columbia, S.C.), October 25, 1893, p. 8.

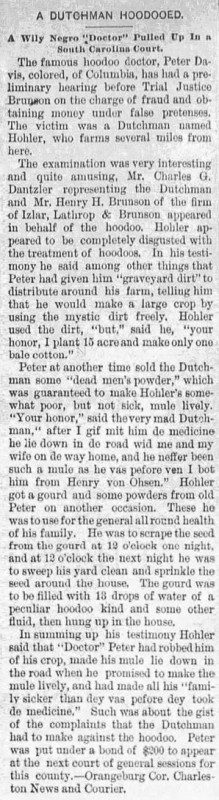

“A Dutchman Hoodooed: A Wily Negro ‘Doctor’ Pulled Up in a South Carolina Court,” Charlotte (N.C.) News, November 15, 1893, p. 3: “Peter had given him ‘graveyard’ dirt to distribute around.”

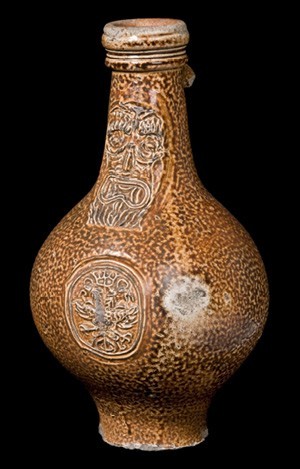

Bartmann or Bellarmine bottle, Frechen, Germany, ca. 1650–1680. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 8 5/8". (Courtesy, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, 1910.18.1.) This vessel was recovered in 1904 during excavations in Westminster, London, and donated to the Pitt Rivers Museum by Edward Warren. Once sealed with a cork, its contents suggest it was used as a “witch bottle.” For more information, see http://objects.prm.ox.ac.uk/pages/prmuid25735.html.

Contents of the bottle illustrated in fig. 25, which include a coarse-fabric cloth heart stuck with straight pins, human hair and fingernail clippings, and a cork stopper. (Courtesy, Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, 1910.18.2–4.) For more information, see https://www.museumof london.org.uk/discover/sorcery-display-witch-bottles.

Fragmentary glass wine bottle and associated contents. (Courtesy, Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab, Jefferson Patterson Park and Museum.) An example of an eighteenth- or nineteenth-century witch bottle burial was found at the White Oak site in Dorchester County, Maryland. A wine bottle neck, horseshoe, bottle glass sherds, and bone fragments were beside a brick hearth. Several straight and bent pins had been inserted into a solid stopper in the bottle neck, both on the inside and outside of the bottle.

Face vessels, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1850–1860. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. of the tallest 5 1/2". (Private collections.)

Detail of the face vessel illustrated on the left in fig. 28 showing traces of red pigment for the eyes and pupils.

Detail of the face vessel illustrated on the right in fig. 28 showing the hole in the bottom.

Ointment or salve jar, possibly Virginia, Maryland, or Pennsylvania, ca. mid-nineteenth century. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 3 3/8". (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation.)

Illustration of Angelica archangelica (Archangelica officinalis), commonly known as garden angelica or wild celery. Chromolithograph on paper. 8 x 10". From Köhler’s Medicinal Plants, by Hermann Adolph Köhler, edited by Gustav Pabst (Germany: Köhler, 1887). (Author’s collection.)

Detail of the jar illustrated in fig. 31.

Flask, American or possibly Asian, nineteenth century. Stoneware with cobalt decoration. H. 5 3/4". (Courtesy, Rick Meech Burchfield.)

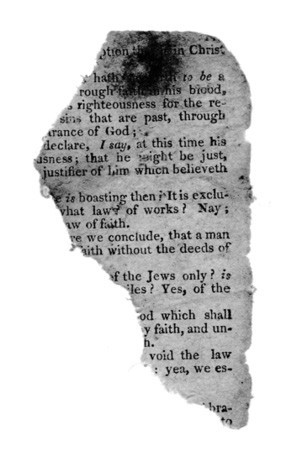

Fragment of a page from a King James Bible, probably nineteenth century. It contains partial verses from Romans 3:25–31.

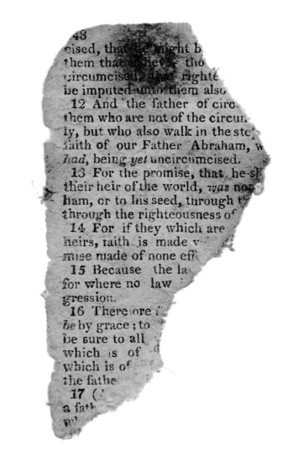

Reverse of the page fragment illustrated in figure 35. It contains partial verses from Romans 4:11–17.

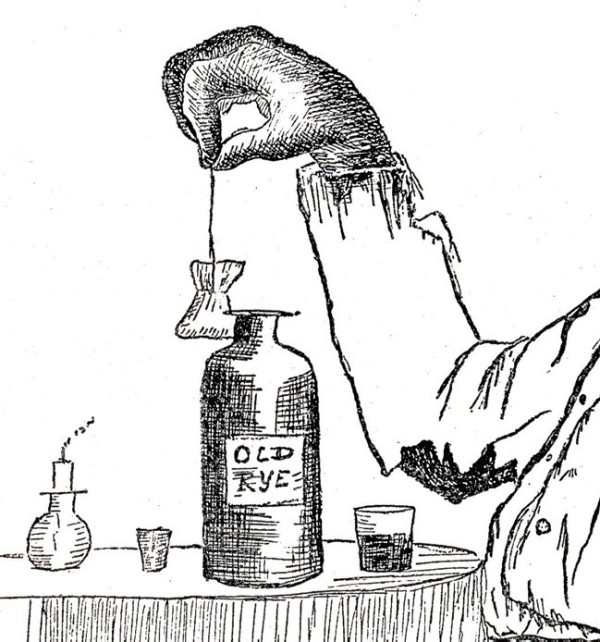

Detail of the 1893 King of the Voodoos engraving illustrated in fig. 39. This 1893 detail emphasizes the use of whiskey as one of the primary ingredients in a variety of hoodoo rituals.

Immagine del manoscritto Zoroaster Clavis Artis, MS. Verginelli-Rota, Biblioteca dell’Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Roma, 2:18 (1738). (Photo, The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo.)

Louis Wain, “King of the Voodoos,” in Owen, Old Rabbit, the Voodoo, and Other Sorcerers (1893), p. 172.

“The Blackville Gallery,—No. IV,” Leslie’s Weekly, January 20, 1898, pp. 40–41. Copyright by Knaffl & Bro., Knoxville, Tennessee, 1898. Photogravure. 22 x 16". (Author’s collection.) The image shows a fortune teller reading the palm of a society lady as the fortune teller’s partner smokes a long pipe next to the fireplace. The caption under the title reads, “A Blackville Fortune Teller,”—“Lawd, Chile! Yo Gwine to Marry Rich.”

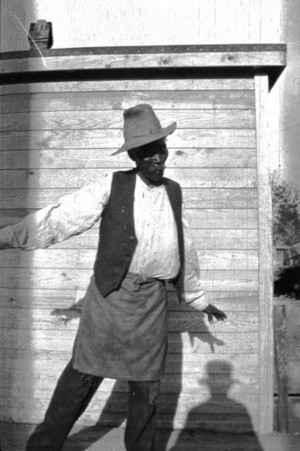

“Mississippi Hoodoo Doctor,” 1920–1940. Gelatin silver print. From Photographs from the Puckett Collection: Folk Beliefs of African Americans in the Southern United States. (Cleveland Public Library, Fine Arts and Special Collections Department; photo, Newbell Niles Puckett.)

Conjure objects from the practice of Mrs. Mamie Wade Avant DeVeaux of Savannah, Georgia, mid-twentieth century. (Mamie Wade Avant DeVeaux Archive.) The objects include a string of beads and dice, playing cards, a heart-shaped mojo bag, and a container of “Blue Stone” (copper sulfate.) Bluestone is a traditional magical substance used for making mojo hands and luck balls for protection and good luck.

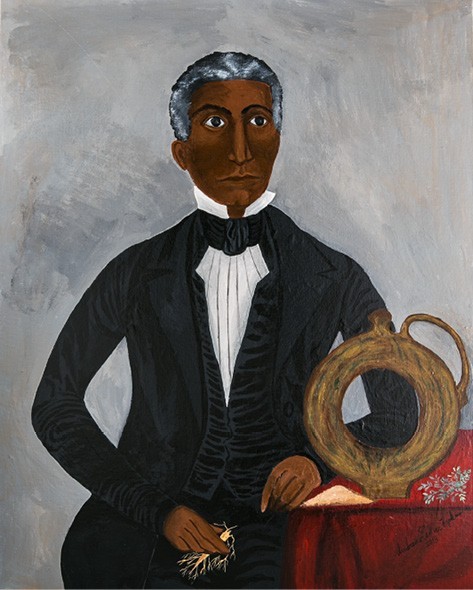

Andrew Hopkins, Dr. Peter Davis, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2017. Acrylic on board. 16 x 20". (Author’s collection.)

Andrew Hopkins, Marie Laveau, New Orleans, Louisiana, 2017. Acrylic on board. 16 x 20". (Author’s collection.)

Anvil dust sourced from Colonial Williamsburg’s blacksmith shop. Anvil dust, the metallic residue created during the blacksmith’s forging process, figures prominently in the practice of conjure and hoodoo. The 1928 Ma Rainey tune “Black Dust Blues” is a classic tale of “goofering,” a synonym for hoodooing. In it, Ma Rainey sings “Black dust in my window, black dust on my porch mat / Black dust’s got me walking on all fours like a cat.”

Modern-day hoodoo materials—including hoodoo water, graveyard dirt, deadmen’s powder, lodestones, gourds, and “roots”—alongside a replica of Dr. Davis’s ring bottle. Those ingredients were used in the “treatment” of Adolph Holuv and his family as gleaned from the newspaper accounts of Dr. Davis’s 1893 court proceedings. (Private collection.)

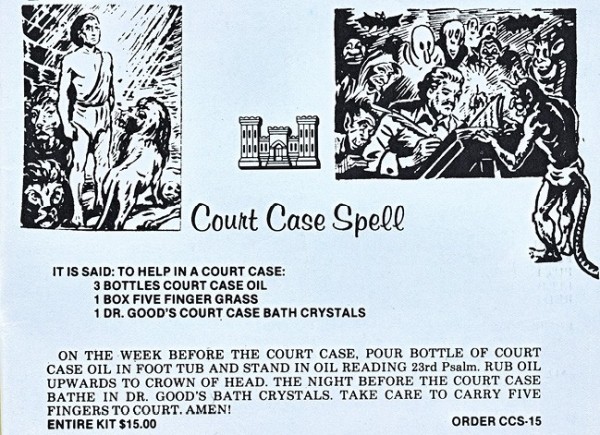

“Court Case Spell” (Order CCS-15), Ritual Supplies Mail Order Source Occult Supplies!, ca. 1960–1970. (Mamie Wade Avant DeVeaux Archive.) A page from a catalog for Miller’s Rexall Drugs, 87 Broad Street, S.W., Atlanta, Georgia, 30303.

Court Case Spell Kit, Lucky Mojo Curio Co., Forestville, California. Powders, oil, mojo bag, and nine candles. (Author’s collection.)

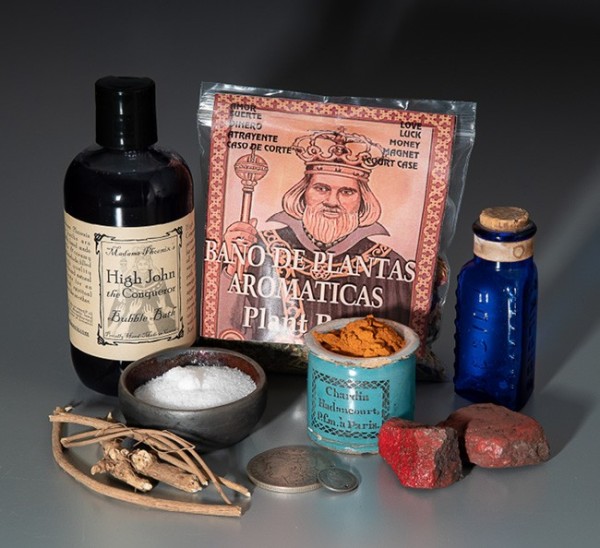

A group of hoodoo objects and ingredients mentioned in “Folk-Tales and Conjure,” Southern Workman and Hampton School Record 28 (March 1899): 112. (Author’s collection.) The “Remedies to Cure Conjuration” include High John the Conqueror plant bath, salt, cayenne pepper, devil’s shoestring roots, red lodestone, and nineteenth-century American silver coins.