Mark Shapiro at his traditional treadle wheel with a six-and-a-half-pound ball of clay. (Unless otherwise noted, all photos by Eli Liebman.)

Jar, Thomas Commeraw, New York, New York, ca. 1810. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 12". (Private collection; photo courtesy Brandt Zipp, The Thomas Commeraw Project.)

Reverse of the jar illustrated in figure 2.

Detail of the handle on the jar illustrated in figure 2.

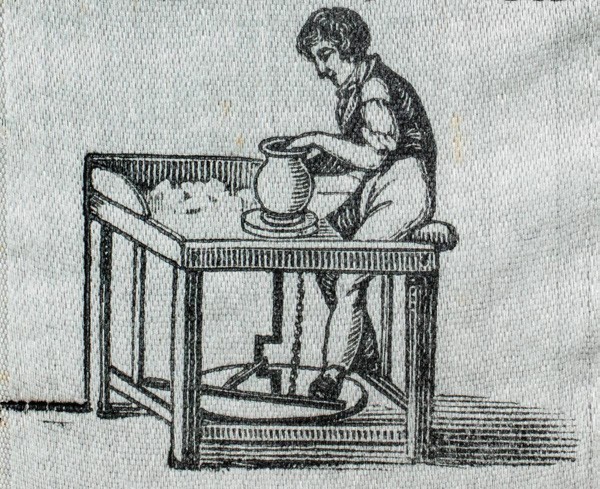

Detail of 19th-century Potter’s Society ribbon. (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society.) The printing die used to make this image of the wheel on that ribbon was in the possession of the Crolius family.

Centering the clay.

Opening the clay ball.

Raising the walls.

Smoothing and shaping the walls with the flat side of a wooden rib.

Profiling the foot detail with a rib.

Profiling the transition between the body and neck. The half-round carved-out cross section of the rib was used to make the bead.

The finished jar is cut off the wheel head with a twisted wire.

Pulling a round cross section of clay to make the free-standing handles. (Historically, this could have been done by extruding clay contained in a rectangular box through a wooden die with a plunger.)

Equal lengths for symmetrical handles are cut and reserved.

Ends of handle are thickened by tapping with a finger.

The placement points of handle attachments on the pot are marked in slip (fine wet clay).

Slip is scored to provide a solid connection between parts.

One side of a handle is attached to the pot.

Second side of the handle is attached.

Second handle has been attached, and one side is worked upward toward the neck to form a period free-standing handle.

Second side is worked upward.

A small coil of clay is added as a backfill to thicken the attachment.

Backfill clay is smoothed in.

Stamping the lune part of the swag-and-tassel motif.

Stamping the tassels.

Stamping a bowknot on reverse.

Lunes, showing broken line on upper arcs. (Collection of the author.)

Stamps fabricated from bent and soldered copper and brass strips.

Mounted typography stamps.

Morgantown stamp in a chase. (Courtesy, Collection of the Smithsonian Museum of American History.)

Stamping typography.

Filling stamped motifs with cobalt. The cobalt here is in carbonate form; it fires to a strong blue.

Painting handle attachments.

Wadded bisque-fired jar. While the original went into the salt kiln in the green state and would have been heated slowly through the initial stages of the firing to prevent cracking and explosions, I did a preliminary firing to enable faster gaining of early heat. Note that the previously pink cobalt carbonate is now blue.

Jar loaded in the kiln. My kiln is a downdraft catenary arch with two fireboxes on the sides. Commeraw’s kiln was probably an updraft, with multiple roof openings and the firebox underneath the floor.

Finished jar.

I HAVE BEEN MAKING wood-fired and salt-glazed stoneware pottery for nearly four decades (fig. 1). The rich and varied textures of these pots are born of a chemical union of clay and glaze. Sodium vapor is liberated at peak temperature, melding with the free silica in the clay to form a hard, orange-peel-like glass over the surface of a pot. The flame’s path pulls the sodium (and wood ash) around and through the kiln, depositing a varied gloss across the skin of the wares. Just as the potter’s hands mark the pot, its surface is marked in its journey through the firing. This compelling alchemy connects the beholder to the palpable presence of maker, material, and process.

Salt glazing developed over centuries, from its German discovery in the fourteenth century, through its many variations there, its adoption in England, and its migration to North America.[1] Brought from the Rhineland to New York City in the 1720s by the Crolius and Remmey families, salt-glazed stoneware flourished in the city from the last quarter of the eighteenth century through the first third of the nineteenth, nourished both by the abundant clay beds in nearby New Jersey and by the rapidly expanding post-Revolutionary population and economy. The excellence of the city’s stoneware was recognized in its day—it was the standard by which competing makers compared their wares. From the time when public institutions first collected early stoneware, New York’s potters were given pride of place.

I have been inspired by these wares since I built my kiln in 1988, visiting museums and absorbing the books available at the time.[2] The John P. Remensnyder collection, mostly acquired by the Smithsonian Museum of American History, seemed to include many of the best examples, so in 2018 I applied for and received a Smithsonian Artist Residency Fellowship to study their stoneware holdings, which are rarely on view. The collection includes some of the finest unmarked eighteenth-century incised wares as well as many later marked ones. The museum holds a dozen or so pots by the New York potter Thomas W. Commeraw (1771 or 1772–1823) made between about 1797 and 1819 and numerous examples made by his peers.

During my residency, I was astounded to learn of Brandt Zipp’s discovery that Commeraw was of African descent.[3] Prior references had universally assumed his white identity. Commeraw worked squarely in the European-derived New York stoneware style; his work bears a practically familial resemblance to that of his white European-descended contemporaries, such as David Morgan, the multi-generational Remmeys, and the Croliuses, the latter of whom had in fact enslaved and manumitted Commeraw’s family, and probably trained him. While awaiting publication of Zipp’s research, I decided to dig in to understand as much as I could about Commeraw myself.[4]

Beyond the excitement of learning about Commeraw’s remarkable life, I wanted to explore the specific techniques that Commeraw used to make his extraordinary pots. After dabbling at making Commeraw’s various forms—oyster jars, jugs, and jars—I chose to reproduce a classic jar with free-standing handles and Commeraw’s stylish stamped swag-and-tassel (figs. 2, 3, 4). To me, this jar is an exemplar of the highest-quality production ware coming out of Commeraw’s workshop. My reproduction was thrown on a foot-powered treadle wheel similar to one depicted on a nineteenthcentury New York Potter’s Society ribbon (fig. 5).[5] The jar form is an ovoid with a wide rim of particularly pleasing proportions, lovely and sturdy free-standing handles, and nice reeding at the foot and between the body and neck.

Making a swelling ovoid form like this was familiar to me given my long interest in early American pottery (figs. 6–23). But Commeraw’s surface decoration was another matter. How did he produce his iconic motifs? Why did he employ quirky stamped typography with inconsistent font sizes and a backward S and N—a seemingly anomalous choice given the evidence of his literacy in his writing and the flowing confidence of his signature on an extant document.[6] Commeraw would have known the proper orientation of these letters.

The swag-and-tassel motif, where he used it, would have been on both the front and reverse, wrapping the pot (figs. 1–2). I reproduced the motif on one side and instead made a bowknot figure (also called a clamshell) on the back using the same metal stamps (figs. 24–26). Commeraw generally put variations of these bowknots on jugs (narrow-necked, with a single handle on the back), but for some reason, not on his jars. But I wanted to demonstrate on one pot the flexibility of Commeraw’s stamping methods.

At first I was unclear as to whether Commeraw’s motifs—especially his swags (also called lunes)—were either stamped, or traced around or inside a template. The occasional doubled-up lines on some examples first led me to think that he used a stylus and that the template had shifted where the line was over-drawn. But the consistency of the marks of the lune figures (some pots show the stamp’s wear or flaws), as well as the quality of the line made by stamping, confirmed that this was indeed Commeraw’s method. The same wear or idiosyncrasy of certain stamps appears across multiple pots (fig. 27).[7] Additionally, the fussiness of tracing with one hand while holding a template with the other argued for a more efficient method. In fact, my experiments with the stamp showed that occasional double-struck and overlapping lines were indeed a byproduct of stamping. In applying the stamps, I saw that this was an extremely efficient means of rendering these designs onto clay surfaces.

I fabricated the stamps from brass and copper stock that I had on hand, bending and soldering strips to form cookie-cutter-like components that can be repeatedly impressed into leather-hard clay using a variety of strategies (fig. 28). Linked or inverted, the same stamps can create swag-and-tassels or bowknots. Unlike Commeraw’s (and his peers’) earlier freehand incising, the stamps provided consistency and identity: a Commeraw pot’s stamped motifs make it instantly identifiable from across a room.[8] For almost two decades, he used the lune and tassel stamps to make the swag-and-tassel and bowknot motifs that built his brand. Emblazoning his wares with these bold logo-like emblems distinguished his wares from others.[9] These stamps also would have enabled others working in his shop over the years to consistently produce his decorations with minimal training and oversight.

In addition to his recognizable motifs, his large and quirky typography let everyone know he was the pot’s maker. He used an emphatically possessive backward .S at the end of his name, unlike his competitors who simply stamped their name or name plus “MANUFACTURER” or “FACTORY,” et cetera. Here was a man who called attention to his personal role in production and his ownership of the workshop. Commeraw also made known the location of his shop to future buyers. This became common practice for potters during this period, and indeed, invoking New York added value to wares sold farther afield.

Commeraw’s typography appears to have been assembled from individual letters into five independent lines: COMMERAW.S, STONEWARE, CORLEARS, HOOK, and N.YORK, with each line of type clamped into a chase or holder. These could have been made from repurposed type, which would explain why the C in Commeraw (and in “CORLEARS”) is slightly tilted and of a smaller type size. Similarly, the S at the beginning of “STONEWARE” is smaller, and other letters within “CORLEARS” vary in size as well. But why, where, and how were the backward S in “COMMERAW.S” and the backward N in “STONEWARE” made?[10] Typographic letters, of course, are fabricated backward so when stuck, they read forwards. Simply rotating type 180 degrees does not render a backward letter; it just makes it upside down. Did Commeraw intentionally fabricate these backward letters by carving or casting them in correct orientation to grab attention as they were rendered on the pot backward? Was he purposefully jarring the norm?[11] I find the lines with the reversed letters strangely visually compelling. The backward possessive .S draws the eye, providing emphasis where Commeraw may very well have wanted it.

The lines of typography for this reproduction were made using images of text taken directly from Commeraw’s pots, producing 3-D files of them (thirteen percent larger to account for drying and firing shrinkage), and sending them out to be 3-D-printed on hard plastic strips—hardly period-appropriate, but expedient. I mounted them on wooden backings based on the Morgantown chase, added handles, and impressed them into the leather-hard clay (figs. 29–31).[12]

I filled the stamped motifs and letters and painted around the handle attachments with cobalt mixed with flux and some clay binder (figs. 32–33). To prevent the base from sticking in the kiln, the jar was wadded with a mixture of refractory clay and sand (fig. 34). I salt- and wood-fired the jar (figs. 35–36) but was not able to reproduce the original’s whitish clay body.[13] Certainly, my clay had too much iron content: Commeraw’s pot would have had a lighter, more kaolinitic body—or would have been fired in a more oxidized atmosphere.[14] Commeraw would have obtained his clay from the Morgan clay banks in New Jersey. Apparently Morgan clay was graded, as is suggested by a materials list from Nathaniel Clark in upstate New York from later in the century. Clark’s list refers to “Morgan’s Best,” which Clark mixed with twenty-five-percent Long Island clay (presumably of lower quality and likely iron-rich) as well as white sand.[15] The free-standing handle jar example would have been made using a light-burning clay readily available at the time, perhaps selected for a particular run of ware.[16]

Much can be learned from copying pots. Just as drawing is said to be a way of learning to see, the same can be said for the exercise of rendering in raw clay fired pots made by past (or present) masters. By reproducing proportions, surface quality, weight, transitions among parts, and so on, one gains intimate knowledge of the strategies and subtleties of another potter’s artistry. The process provides a window into the creative activity of another’s consciousness, outside the limitations of one’s own time and habits. Hardly anyone makes sturdy freestanding handles like these anymore, and it was magical to bend those horizontal loops upward to form that graceful curve rising toward the rim (figs. 20–21). Nor would a studio potter today broadly stamp his or her name across the face of a utilitarian jar, nor make one so sturdy. The reeding gives the jar a classical touch—something almost architectural from another time, though even in its own moment it was referencing an earlier time (figs. 10–11).

For me, making this pot was purely a heuristic and technical exercise, not to be confused with my own creative expression. While we are a social and mimetic species—human knowledge as embodied in objects is incremental and builds on the legacies of past makers—we participate in the human community most fully by making things that are for and of our own time and place. Thomas Commeraw made his outstanding pots within an idiom built on centuries of European stoneware potters filling and firing kilns and practiced by the New York City potters who trained him and with whom he competed—some of whose predecessors, even, had enslaved him and his family. His own works were both selfand culture-defining. His stylish and efficiently decorated wares were instantly identifiable as embodiments of his creative authority and identity as an independent master craftsman.

High-fired stoneware was first developed in China in the fourteenth century BCE and independently arose in Europe during the late Middle Ages.

In particular, Georgeanna H. Greer, American Stonewares: The Art and Craft of Utilitarian Potters (Exton, Pa.: Schiffer Publishing, 1981); William C. Ketchum Jr., Potters and Potteries of New York State, 1650–1900 (Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 1987); Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1968); and Donald Blake Webster, Decorated Stoneware Pottery of North America (Rutland, Vt.: C. E. Tuttle, 1971).

A. Brandt Zipp, Commeraw’s Stoneware: The Life and Work of the First African-American Pottery Owner (Sparks, Md.: Crocker Farm, 2022).

Over the last several years I provided historical research for and co-curated the 2023 exhibition Crafting Freedom: The Life and Legacy of Thomas W. Commeraw at the New-York Historical Society (January 27–May 28, 2023) and at the Fenimore Museum of Art (June 24–September 24, 2023).

British studio pottery pioneer Bernard Leach (1887–1979) popularized the use of traditional treadle wheels and even had them manufactured, though they are rarely used today since electric-powered wheels have supplanted treadle and other styles of kick wheels.

Commeraw’s signature appears on an 1813 Certificate of Freedom for Peter Johnson of “Brooklyn, Long Island.” These certificates included a statement attesting to the free status of the applicant and were required after 1811 for free Black men to vote (Patricia D. Klingenstein Library, New-York Historical Society).

Commeraw used nearly a half-dozen different tassel stamps and several different lunes over his career. The variations are extremely minor (except for one tassel that is more of a single leaf, shown in fig. 27).

Commeraw’s earliest works had free-hand incised and blued floral figures front and back and were impressed with “COERLEARS HOOK” on one side of the rim (he used an extra E in this earlier spelling) and “N.YORK” on the reverse. The floral incising was similarly used by his peers.

There is a period (ca. 1798–1803) when his neighbor, David Morgan, also used related stamped motifs. It is unclear whether Morgan was a competitor, collaborator, or both.

The N in “N.YORK” is, in almost all cases, normally oriented except for a few spectacular highly marked three-gallon jugs, where it oddly appears backward.

The cigarette marketing tagline “Winston tastes good like a cigarette should” purposefully eschewed the proper “as” in the famously successful campaign to gain attention. Walter Cronkite, in defense of linguistic propriety, refused to utter the phrase on air.

I am grateful to Rowan McAllister and Jason Miller for their invaluable help with this technology.

My salt glaze came out a little heavy as well.

Oxidation and reduction effects can result from placement in the kiln setting—wood kilns have microclimates of varying atmosphere—or from the ratio of fuel to air as a result of the amount and frequency of the stoking cycle, as well as air intake and outflow settings.

Webster, Decorated Stoneware Pottery of North America, p. 38. Commeraw achieved a wide range of body color in his production, from off-white to rich brown. Some of this would have been due to the clay body he used (perhaps a higher percentage of Morgan’s Best), as in several extant off-white profusely stamped decorated and three-gallon jugs, which oddly bear a backward N in “N.YORK.”

Where the same pots show color transition from light to dark, we can assume that reduction and oxidation microclimates in the kiln are the cause.