Oyster jar, Thomas Commeraw, New York, New York, 1799–1804. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/4". (Unless otherwise noted, all objects from the author’s collection; photo, Rory MacNish.) This oyster jar, marked “DANIEL | JOHNSON.AND.CO NO. 24 | LUMBER STREET | NEW.YORK,” is surrounded by large live New York oysters and a period cast iron oyster knife. Found in Guyana, the jar has the less common “NEW.YORK” imprint rather than the more typical “N.YORK.”

Oyster jars, attributed to Thomas Commeraw, New York, New York, 1797–1805. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. (of tallest) 8 7/8". (Photo, Christopher Pickerell.) The tall jar at center was recovered by a diver off the island of St. Croix. The other jars were all found in coastal Guyana. The jar at far right is pictured in detail in figure 1; the jar second from right is an unmarked example that is identical in size, glaze, and gallery details to a Commeraw jar made for New York oysterman George White in the author’s collection. The two Daniel Johnson jars on the left appear to have been made by the same hand given the identical impressions and similar gallery details. The differences in color and texture are likely due to varying conditions in the kiln during firing (i.e., oxidation and reduction).

Oyster jars, various makers, 1774–1850. Albany-slipped and salt-glazed stoneware. H. (of tallest) 9". The earliest example is shown second row far left, recovered in Guyana. The pieces shown in the two front rows and the large Albany slip-glazed collared example in the back row were likely produced for the New York market. The smaller dark brown glazed collared example, second row far right, was recovered in Hamilton Harbor, Bermuda, and the orange-brown example, front row far right, was recovered in St. Georges Harbor, Bermuda. The three salt-glazed examples in the back row were made for the Baltimore market. The examples on the ends are both marked “E.DERLIN” and made for Edward Derling, a white man who ran an “oyster house” on Caroline Street south of Bank St. in 1835-36.

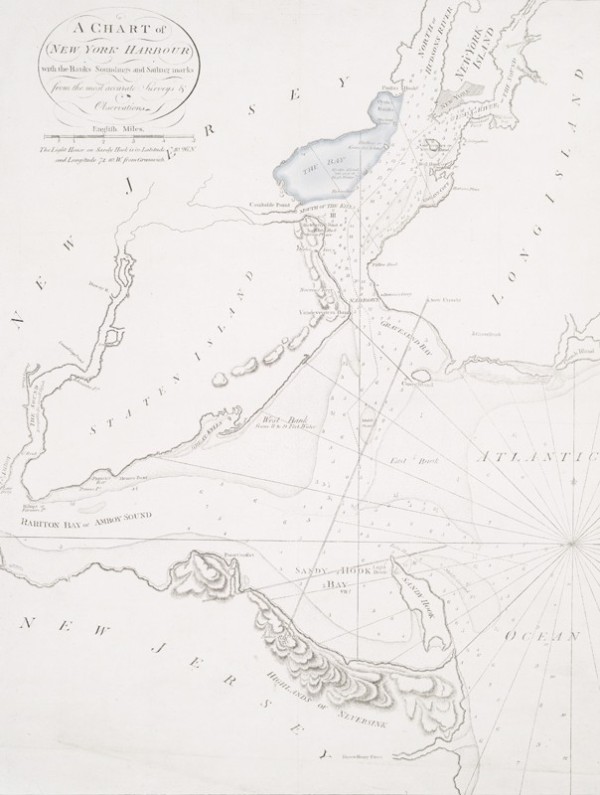

Jno. Mount and Tho. Page, A Chart of New York Harbour, with the Banks Soundings and Sailing Marks from the Most Accurate Survey & Observations. (London, 1794), paper, 24" x 18". (Courtesy, New York Public Library.) New York Harbor as it appeared in the third quarter of the eighteenth century. Note the area designated as “Oyster banks” due west of the southern tip of Manhattan, just south of Paulus Hook, New Jersey. The area denoted in light blue on the map, from Paulus Hook south along the Bayonne shoreline, represents the primary oyster grounds of the early fisheries.

Pickled oysters prepared by the author using a modern adaption of a traditional recipe. Jarred oysters would have been poured onto a dish or into a bowl to eat. These large oysters were the preferred size for pickling compared to the much smaller cocktail-sized oysters served on the half shell today. (Photo, Christopher Pickerell.)

Oyster jar, London, England, ca. 1806. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. approx. 5 1/2". (Private collection.) This small jar marked “Sommervail’s Oysters” was found in London. Despite the fact that Sommervail listed the sale of several sizes of jars in his advertisements, this is the only marked example known to the author.

Oyster jar, probably New York, New York, 1759–1760. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Parks Canada; photo, Karolyn Gauvin.) This is one of six oyster jars recovered from the hold of the French frigate Machault, which sank in the Restigouche River during a battle with the British in 1760.

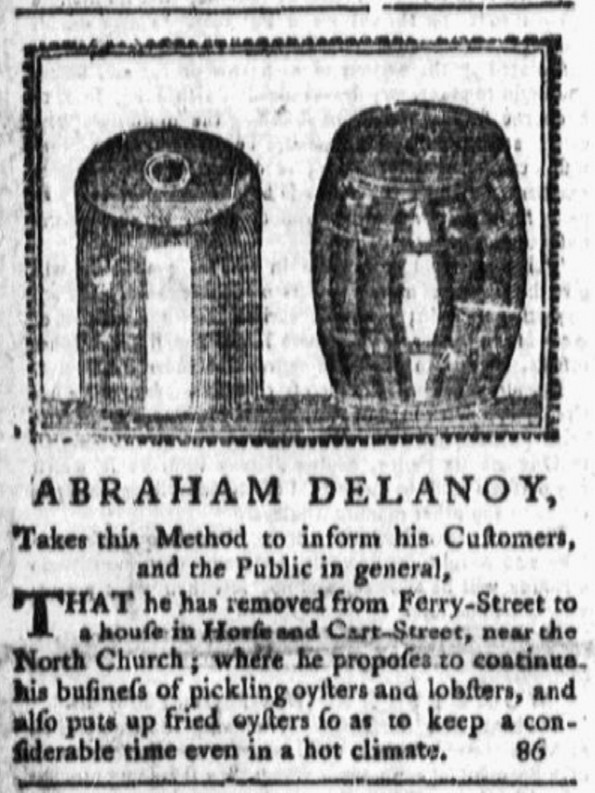

Advertisement for Abraham Delanoy in Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, June 16, 1774. This woodcut printed image of the jar and keg was used by Delanoy sporadically in this newspaper from June 16, 1774, until December 13, 1775. (Readex, America’s Historical Newspapers.)

Re-creation of Abraham Delanoy’s advertisement in figure 8. Note that the keg pictured here is a later version with metal hoops, while a keg from the 1774–1775 period would have been made with wooden hoops.

Oyster jars, New York, New York, 1780–1800. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. (of tallest) 6 1/2". Included in this group of early oyster jars are at least two (back row far left and far right) that have been attributed to Thomas Commeraw. Note how the inner rim of several of the openings of these jars is flush or nearly flush with the shoulder, while the others are so shallow as to preclude the use of anything other than a cork to seal them. These slightly recessed galleries would have helped to retain the wax or pitch used to seal the cork.

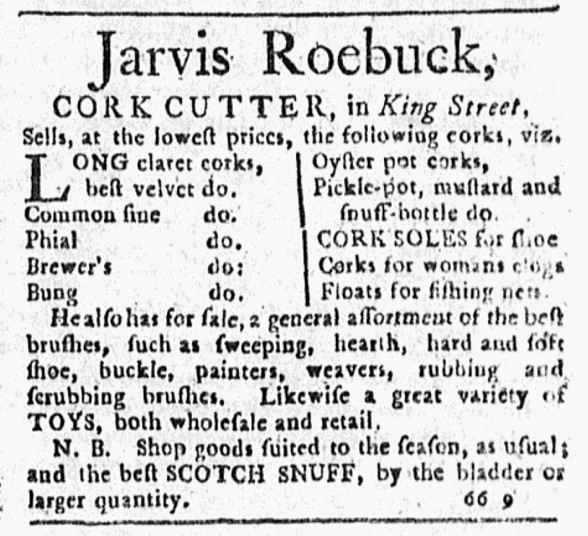

Advertisement listing “Oyster pot corks” placed by Jarvis Roebuck, General Advertiser, December 8, 1774. (Readex, America’s Historical Newspapers.)

Mark Shapiro turning a Thomas Commeraw-type oyster jar at his studio, Stonepool Pottery, Worthington, Massachusetts, on June 14, 2022. (Photo, Christopher Pickerell.)

Oyster jars, probably Connecticut, 1830–1845. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. (left) 6 1/2", H. (right) 6". The jar on the right is stamped “HENRY SCOTT | 217 WATER STREET | NEW YORK.” The distinctive lettering on the Scott jar matches that on most of the Thomas Downing jars and is identical to that found on two jugs produced in Norwalk, Connecticut, thus pointing to a Connecticut manufacture for these examples.

Oyster jars, probably Alexandria, Virginia, ca. 1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. (of tallest) 8 1/2". These jars were almost certainly produced by an Alexandria potter for the Baltimore or Alexandria market. They were recovered together in a Sacramento, California, hotel privy in a circa 1850 context.

Finds map for seventy of the eighty-five surviving jars known to the author. This information is based on data gathered from divers, bottle diggers, auction records, archaeological reports, and private collectors.

Detail of the base of a Commeraw-type oyster jar recovered by Teddy Tucker in Bermuda. (Courtesy, Wendy Tucker; photo, Christopher Pickerell.) Note the marks made by the feeding activity of a parrotfish.

AMONG THE MORE DISTINCTIVE ceramic pots produced in New York City during the first years of the nineteenth century are the stoneware oyster jars made by Thomas Commeraw (1771 or 1772– 1823), the free Black potter working at Corlears Hook on the Lower East Side of Manhattan (figs. 1–2).[1] These small cylindrical jars, often marked with the name and address of the oysterman who filled them, have been recovered at coastal sites throughout the Atlantic world.

While Commeraw’s jars are the most well known, he was not the first or only potter making them. A rudimentary type first appeared in New York in the mid-eighteenth century, long before Commeraw was in business, and a more refined collared version was being produced well after his death (fig. 3). Regardless of who made them, considerable evidence points to the fact that these jars played a unique and enduring role in trade from the port of New York during the latter years of the age of sail, from the mideighteenth into the first half of the nineteenth century.

Due to their gastronomical renown, pickled oysters were among the more sought-after and costly pre-packaged provisions available to sea-going travelers during this period. While salted beef, biscuits, peas, and grog were common shipboard fare, captains and other traveling gentlemen often supplemented or replaced those with their own private stocks, including fresh meats, fruits, fine wines, and jars of pickled oysters from New York. While on board, these men of power and privilege often exchanged and shared such delicacies.[2] Following these meals, empty jars would have been tossed overboard, leaving no trace of the sturdy containers that had so ably protected their perishable contents.[3]

For all these reasons, oyster jars made during this period are inextricably linked to the sea, from the briny oysters they were designed to hold, to the watery grave where most now lie. These simple ceramic pots serve as unique and enduring touchstones to a long-forgotten past involving the sometimes profitable and often perilous adventures of men and ships.

New York As a Center of Oyster Production

In its unspoiled state, New York Harbor was as close to a perfect oyster nursery as Mother Nature could devise, and few places on earth challenged this supremacy (fig. 4). The waters around Manhattan Island, and those bordering Staten and Long Islands, were home to some of North America’s most productive oyster grounds, which had been providing food for the native Lenape people for more than three thousand years before Dutch settlers arrived.[4]

With an appreciation for the oyster refined over centuries, the first European inhabitants of New Amsterdam/New York were initially content to consume the harbor’s bounty themselves, but they quickly realized that this valuable and abundant commodity could be exported for profit as part of the city’s lucrative trade with the West Indies, a group of islands separating the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea from the Atlantic. In 1679 Jasper Danckaerts wrote that the residents of Brooklyn “pickle the oysters in small casks, and send them to Barbados and the other islands.”[5]

By the mid-eighteenth century, New York City was world renowned for the quality and size of its oysters, and in 1748 Finnish botanist and naturalist Peter Kalm noted:

. . . in their Quality they are exceeded by those of no Country whatsoever. People of all ranks amongst us in general prefer them to any other kind of food . . . they continue good eight months in the year, and for two months longer the daily food of our poor . . . .[6]

Kalm was referring to the seasonal restriction on harvest, which was designed to protect both the public from sickness and the oysters from overharvest. While city officials looked the other way when the poor fed themselves on oysters harvested in May and June, in truth only preserved oysters could be sold legally between May and August. This meant that anyone who wanted to enjoy this most favorite of New York foods during the summer months would have had to partake in those that had been previously “put up.” Given the high demand for oysters year-round, the labor involved in pickling them, and the fact that they had a shelf life of six months or longer, pickled oysters were considerably more expensive than those in the shell, putting them out of reach for many Manhattan residents.[7]

This opportunity to make a significant profit from what was an otherwise plentiful and inexpensive commodity was not lost on New York merchants—as previously noted by Danckaerts—and seventy years later the practice was still commonplace as noted by Kalm:

. . . the merchants here buy up great quantities of oysters about this time, pickle them in the above-mentioned manner, and send them to the West Indies: by which they frequently make a considerable profit: for, the oysters, which cost them five shillings of their currency, they commonly sell for a pistole, or about six times as much as they gave for them; and sometimes they get even more; the oysters which are thus pickled have a very fine flavour.[8]

The Pickled Oyster

Although unknown to all but the most avid of oyster enthusiast today, pickled oysters would have been familiar to everyone living in eighteenthand nineteenth-century New York as this food enjoyed a prominent role in the foodways of early modern Europe. . Recipes for pickling oysters are known from as early as the seventeenth century in England, where they were often served at royal banquets and other important celebrations.[9] From this period forward, they continue to appear in cookbooks until well into the nineteenth century.

Methods for pickling oysters didn’t vary significantly from the earliest days. In all cases, the oysters were boiled in water, then combined with vinegar, spices, and often salt, to give them a distinct flavor (fig. 5). A particularly detailed and informative recipe published in 1747 uses ingredients common to most recipes:

Take two Hundred of Oysters, the newest and best you can get, be careful to save the Liquor in some Pans as you open them, cut off the black Verge, saving the rest, put them into their own Liquor, then put all the Liquor and Oysters into a Kettle, boil them about Half an Hour, on a very gentle Fire, do them very slowly, skimming them as the Scum rises, then take them off the Fire, take out the Oysters, strain the Liquor through a fine Cloth, then put in the Oysters again; then take out a Pint of the Liquor whilst it is hot, put thererto three Quarters of an Ounce of Mace, and Half an Ounce of cloves; just give it one Boil, then put it to the Oysters, and stir up the Spices well among the Oysters; then put in about a Spoonful of Salt, three Quarters of a Pint of the best White Wine Vinegar, and a Quarter of an Ounce of whole Pepper; then let them stand till they be cold, then put the Oysters as many well you can into a Barrel; put in as much Liquor as the Barrel will hold, letting them settle a while, and they will soon be fit to eat, or you may put them into Stone Jars, cover them close with a Bladder and Leather, and be sure to be quite cold before you cover them up.[10]

Pickled oysters were no different than other foods preserved under acidic conditions, and early cooks quickly recognized that they needed to store this corrosive mixture in a sufficiently resilient container. In 1756 one writer noted that “nothing but stone or glass will hold pickles, for the vinegar and salt in preparing them, [will] eat through anything else. Glass is too brittle, therefore stone jars are the only proper convenience.”[11]

While stoneware and wooden vessels made with relatively large openings were used in homes and taverns to store quantities of preserved oysters, shipping of single-serving-size portions required a different approach—one that utilized smaller and more rugged containers that could be easily sealed and withstand the rigors of travel. The obvious packaging for this purpose was the wooden keg, which had been in use for centuries to transport all types of liquids, solids, and hard goods. In England, the standard container used to hold small quantities of pickled oysters was a diminutive wooden keg referred to as a “barrel,” of a pint and a half to a quart capacity that held up to a hundred oysters.[12]

Pickled Oysters and Ship Captains

From the middle of the seventeenth through at least the first quarter of the nineteenth century, pickled oysters were closely associated with the men who commanded ships in trade and battle on the high seas. Men of means, including the captain and any gentlemen passengers and guests, would bring their own food, or “cabin store,” on board, often including things like potted oysters. The captain’s cabin was a private space, away from the “men before the mast,” where he could host meals and conduct business. While at sea, he dined there with officers and guests of his choosing. In England, ship captains and naval officials often shared and exchanged barrels of pickled oysters, as evidenced by English diarist and naval administrator Samuel Pepys, who on April 21, 1660, wrote:

In the afternoon the Captain would by all means have me up to his cabin, and there treated me huge nobly, giving me a barrel of pickled oysters, and opened another for me, and a bottle of wine, which was a very great favour.[13]

More than a hundred years later during the American Revolution, in an account that demonstrates both the continuing affinity of a British naval captain for pickled oysters and their value as a prize of war, a jar of pickled oysters was seized from the British schooner Alert that was captured on the Delaware River in 1778 by American Captain John Barry. As proof of conquest, Barry sent the jar and a note to George Washington, then encamped at Valley Forge.[14] Clearly pleased with the prize delivered to him, Washington replied: “accept of my sincere thanks, for the good things which you have been so polite as to send me.”[15]

While naval captains almost certainly purchased jars for their own consumption—and perhaps to share with senior officers and naval officials, as Pepys noted—merchant captains may have had other motivations. In addition to what they could eat themselves, these men likely purchased additional jars of oysters intended as part of a system of private ventures or personal trades.[16] New York pickled oysters were a widely recognized, high-value commodity that could be readily traded at any port, and since these provisions were considered the personal property of the captain and not cargo, they would not have been subject to import duties, thus further increasing profits when sold.

An advertisement from March 16, 1791, in a Philadelphia newspaper demonstrates this practice as it notes the sale of sixty pots of pickled oysters by the master of the sloop New-York Packet, docked at Hodge’s Wharf; a similar advertisement appears in a 1797 Charleston, South Carolina, newspaper offering the sale of “a few pots of PICKLED OYSTERS” from on board the Matilda, a vessel that regularly sailed between New York and Charleston.[17] In both cases the captains appear to have been more interested in making a profit than satisfying a personal craving, although they also might have had their fill of oysters by the time they reached port.

While these general speculative sales were almost certainly commonplace based on such listings, at other times a captain may have had a specific person in mind when he stocked for his journey. As a part of his West Indies trade, a captain might have planned to share with or gift jars of oysters to a wealthy planter he hoped to do business with. Being in good standing with such powerful men could greatly increase the chances of a successful trading voyage, and pickled oysters could have helped with this.[18]

The use of pickled oysters as a gift or informal means of exchange may have contributed to the design and marking of the single-serving oyster jar, allowing for a valued New York delicacy to be safely and conveniently packaged in a way that facilitated its transportation and presentation while also potentially helping to circumvent trade restrictions.[19]

Origins of the Oyster Jar

The first ceramic pickled oyster jars may have actually been produced in England. In 1708 a London merchant advertised the sale of “right Ground oysters pickled to be sold by the Pot for 2s there being 25 large oysters in the Pot.”[20] Although wooden barrels appeared to be the more common means for selling pickled oysters at the time, there is evidence that stoneware jars were also in use throughout the late eighteenth century, with some merchants offering both jars and casks in different sizes simultaneously.[21] In about 1806, a London oyster seller named Sommervail was offering oysters in diminutive, baluster-shaped stoneware jars unlike any ever produced in America (fig. 6).[22]

It is not clear exactly what forces were at play when New York potters first began producing what would become the American version of the oyster jar, but it may have been a simple matter of imitation and opportunity. Given the quantity and quality of oysters available in New York and the chance to make a profit in shipping them abroad, oystermen and merchants would have welcomed any suitable packaging innovation that enhanced shelf life and reduced costs.

The fact that Manhattan was blessed with at least two large stoneware manufacturers meant that the city was prime for innovation in ceramic packaging.[23] For the larger volumes of two to five gallons, wooden kegs were perfectly suitable, and based on newspaper listings and export records, those would remain the standard; but for the single-serving quart and smaller sizes, ceramic containers may have offered advantages over their wooden counterparts.[24]

Oyster Jar Design and Evolution

Given the simplicity of their design and the effectiveness with which they served a single purpose, oyster jars are an almost perfect example of early commercial food packaging in that the form clearly follows the function.[25] However, given that this function centered on the ability to seal the contents from contact with air (and this favored a design with very small openings), it resulted in a container that was nearly useless for any other purpose. In addition to this, the fact that their contents mostly were consumed at sea meant that these jars were discarded immediately, making them possibly the only single-use and disposable stoneware containers produced at the time.[26]

The earliest identifiable oyster jars likely made in New York are a group of six recovered from the French frigate Machault, which sank off the coast of Canada in 1760 (fig. 7).[27] These jars are small (six inches tall and four inches across at the base), straight-sided and cylindrical, with somewhat rounded shoulders and a smooth flat top surrounding a small opening of just over one and a half inches in diameter. There is a hint of a very subtle depression surrounding the opening, but nothing like the later Commerawtype jars that included a prominent and often recessed gallery. The shape of these jars, not unlike modern soda cans, would have facilitated stowing on board in wooden boxes.

From this early design, subtle changes were introduced to the area surrounding the opening, such as an incised groove or slightly protruding ring. This modification was almost certainly intended to help retain the wax used to seal the opening. The details of this can be seen in a 1774 advertisement of Abraham Delanoy of New York (fig. 8). Interestingly, this illustration shows the ceramic jar alongside a similarly sized wooden keg, suggesting that both were used in New York at the time (fig. 9).[28] Given that both the Crolius and Remmey families were manufacturing utilitarian stoneware then, it is reasonable to think that one or both potters were producing such jars.[29] Indeed, about 1810 Clarkson Crolius was offering “oyster pots” at the price of eight shillings each wholesale, one shilling cheaper than the quart-sized mug, but four shillings more expensive than a pint-sized mug, suggesting that the jars were closer to a quart in size.[30]

In addition to stoneware vessels, at least one New York earthenware potter was producing oyster jars. Jonathan Durell, a potter who moved to New York from Philadelphia in about 1771, posted an advertisement dated March 22, 1773, in the New York Gazette listing “oyster pots” among his offerings.[31]

By the time Thomas Commeraw began producing stoneware at his factory around 1797, the oyster jar had evolved into the form we are most familiar with today, including the small size (approximately a pint), straight sides, square shoulder, and distinctive recessed well or gallery surrounding the opening (figs. 2, 3, 10). Ivor Noël Hume theorized that this gallery was designed to receive a small ceramic disk acting as a sort of cap, thus his use of the phrase “cap hole oyster jars” in his well-researched article—but considerable evidence argues for corks as the actual means of closure.[32]

The most convincing evidence for the use of corks lies in the fact that a large number of surviving jars, including several made by Commeraw, have galleries that are not sufficiently recessed to receive such a cap; in fact, some of these have raised or protruding edges to the openings, making the use of a cap impossible. In addition to this, several Manhattan businesses advertised the sale of “oyster pot corks,” suggesting that these were commonly available by the third quarter of the eighteenth century, when oyster jars were in wide use: in 1774 Jarvis Roebuck, a cork cutter on King Street in Manhattan, was selling oyster pot corks; twelve years later, another businessman was selling oyster pot corks at his shop at 44 Maiden Lane; and by 1788 George Warner on Murray’s Wharf offered oyster pot corks among other products (fig. 11).[33]

It is not known whether or not Commeraw played any part in developing or refining the style of the jars he produced, but what is clear is that he was the first to incorporate the names of the oystermen on his pots; of those that can be positively identified, all were African American.[34] Since there were white oystermen working in Manhattan during the same period, it is unclear whether Commeraw made jars for these men as well or if that job fell to the Crolius and Remmey families working nearby.

While the small pint-capacity jars appear to have been the standard size produced by Commeraw and his contemporaries, a few larger-sized jars also survive, suggesting that at least two sizes were being produced (figs. 2, 3). The larger, approximately half-gallon jars, are less common, suggesting that there may not have been as much of a demand for that size. This could be due to the fact that these would have held approximately two hundred oysters compared to the forty to fifty held in the standard-size jars.[35] While forty-five is a somewhat reasonable number of pickled oysters for one individual to eat in one or maybe two sittings, two hundred would have been more appropriate for a small gathering. Regardless of the size, once the jars were opened, all of the oysters would have had to be consumed in relatively short order, since contact with air would cause them to spoil.

To help in determining how these jars could have been made, studio potter Mark Shapiro set out to recreate a typical Commeraw jar at his studio in Massachusetts (fig. 12). Mark was able to demonstrate that these jars could be turned very quickly, and based on this test he estimated that a trained potter could throw several hundred in one day, providing additional weight to the theory that stoneware vessels may have been an easy-to-manufacture and potentially cost-effective alternative to the traditional wooden keg.[36] In addition to this finding, the fact that this simple cylindrical form could be stacked efficiently one on top of the other in the kiln—as evidenced by the pad marks visible on several Commeraw jars— means that the jars would have taken up minimal space in the kiln, allowing for further manufacturing efficiencies.

By about 1830, New York oyster jars had taken on one final design refinement. This form is characterized by straight sides and a sharp and angular shoulder that rises gently to a high and thick parallel-sided or slightly flaring collar. This design, likely introduced by Connecticut potters, for the New York market, represents an improvement over the earlier style as being better suited to receive and hold the cork and for pouring of the contents.[37] While the most well-known jars of this type were made for the Black oysterman Thomas Downing of No. 5 Broad Street in New York, one surviving example bears the mark of another Black oysterman named Henry Scott, who had a stand at 217 Water Street (fig. 13).[38]

At the same time that the improved collared jars were being produced, a jar that has more in common with the earlier Commeraw-type vessels appeared in the Chesapeake region about the same time. This mid-Atlantic type, which may have been introduced by New York potter Henry Remmey (who arrived in Baltimore about 1812) is distinct from the earlier New York types in that the former were more carefully potted and uniform in manufacture, with highly angular and sharp openings compared to the somewhat misshapen and irregular examples produced by Commeraw and others.[39] Two jars of this type were recovered from a circa 1850 Sacramento, California, hotel privy, which points to shipment of Chesapeake Bay oysters to the West Coast via clipper ship (fig. 14).[40] This brief appearance of these jars would mark the last time that ceramic jars would be used in any significant numbers to ship oysters, as metal cans came to dominate the trade by the 1850s.[41]

While it is clear that Commeraw and at least Crolius made oyster jars, it is almost impossible to attribute the maker of individual jars accurately except for marked examples. While various characteristics such as general typology, details of the opening, clay color, and glaze have all been used to make qualitative attributions, this practice is clearly fraught with error.[42]

Where Are All the Jars?

Although thousands of oyster jars were almost certainly produced during the period from 1750 to about 1850, remarkably, less than one hundred are known to this author today. The reasons for this relate to both how they were distributed and aspects of their design that made reuse impractical and disposal likely.[43]

As noted previously, these single-serving-sized jars of oysters were marketed specifically to captains and other gentlemen headed to sea, usually to the West Indies or other southern ports. Depending on the period, customers would have included British or American officers engaged in wartime maneuvers, Atlantic trade, and even privateering. By 1800 there were as many as eight hundred British merchant vessels alone visiting North American ports, and a large number of these would have passed through New York, providing ample opportunity for the export of New York oysters in small jars.[44]

While it is logical to assume that the vast majority of such jars were opened and discarded while at sea, now lying on the bottom of the ocean like countless ceramic breadcrumbs marking the path of these long-forgotten voyages, a much smaller number either never left port or did arrive at some far-off destination only to be similarly discarded. Of the former group, two nearly identical jars were recovered in excavations at Fulton Street, New York City, and are the only jars definitively recovered in Manhattan.[45] From the latter group, shipped abroad and eventually discovered by SCUBA divers searching in shallow harbors or by bottle hunters probing in mudflats and digging in privies, we get the bulk of surviving jars.

A finds map of the approximately eighty-eight jars known to the author confirms distribution patterns related to the routes of trade and warships leaving New York (fig. 15). Here we see that jars have been recovered at sites from Martha’s Vineyard in the north, down to Guyana in the southern Caribbean. The islands of the West Indies, an area that should potentially yield a large number of jars, has of yet only produced one jar, recovered off St. Croix (the large jar at the center of figure 3). For reasons unknown, South America is the area where most oyster jars, especially those produced by Commeraw, have been recovered.[46]

We don’t know whether the jars recovered in Guyana represent a single shipment or are the result of multiple shipments over several years. The latter is more likely given the fact that jars from several different oystermen have been found, and for the most numerous of the group, those made for Daniel Johnson (see figs. 1, 2), the marks vary, indicating what appear to be different batches, with some suggesting a change in partnership for his business.[47] A likely source of at least some of these jars is one particular New York merchant active during the period. Thomas T. Thomson (d. 1807), an attorney from Catskill, New York, a village just up the Hudson from Manhattan, arrived in Demerrara (located in present-day Guyana) in 1803 and acted as an agent for the prominent New York merchants William and John Radcliffe.[48] Soon he was trading in his own right, and in August of 1804 he advertised the sale of pickled oysters among his other goods received from New York, almost certainly in stoneware jars made by Thomas Commeraw or other New York potters.[49]

Of special note among the surviving jars are examples recovered in Bermuda. Here were discovered at least ten jars spanning the period from the 1770s up to the 1840s, indicating regular trade between New York and that island. Notable among the jars recovered is one redware example that may be the product of Jonathan Durrell’s Manhattan pottery, as well as a number of jars clearly produced by Thomas Commeraw. One example is a jar marked with the abbreviated version of Daniel Johnson’s name that is infilled with cobalt matching an example recovered in Charleston, South Carolina, and another found in Guyana.

All of the jars found in Bermuda were recovered by divers probing in protected coves and harbors where British men-of-war, and possibly American trade vessels, moored. While many show evidence of wear and various types of attached marine growth, one discovered by the renowned marine explorer Teddy Tucker shows the tell-tale marks of grazing by a particular type of reef fish. In this case, the edges and opening of the jar show the distinct double-grooved teeth marks of the green parrotfish (fig. 16). While this species typically feeds on attached growth covering rocks and heads of coral with a bite so formidable it reduces both to sand, in this case it chose to feed on an oyster jar.

Despite the small number of jars that are currently known, there is little doubt that more jars will be recovered as historic mooring areas and shipwreck sites in the Caribbean, especially at sites frequented by British ships, are explored. There is even the possibility for deep sea discoveries as petroleum companies continue to map the ocean floor using autonomous underwater vehicles and other means. As these discoveries are made, they will help shed more light on the men who toiled in the waters surrounding Manhattan to harvest oysters—and on those who prepared that delicacy to feed the men who sailed the Atlantic in search of riches and glory through trade and battle.

Ivor Noël Hume, “Cap-Hole Oyster Jars: A Racial Message in the Mud, or, Shipping, Ostreidae Crassostrea virginica,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2011), pp. 150–164.; A. Brandt Zipp, Commeraw’s Stoneware: The Life and Work of the First African-American Pottery Owner (Sparks, Md.: Crocker Farm, 2022).

The practice of gentlemen’s purchasing jars of oysters to eat during long journeys continued well into the eighteenth century, as noted by Josiah Harmar, a Revolutionary War officer and official courier for the Continental Congress who was preparing to leave for France from Manhattan in 1784. In his diary he noted the purchase of “two pots of pickled oysters to go on board”: Dwight L. Smith, “Josiah Harmar, Diplomatic Courier,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 87, no. 4 (October 1963): 425.

Responsible ship captains would have been fastidious about keeping their vessels as clean as possible given the concerns about sickness and disease spreading through the close quarters of the ship. Therefore, there would have been no reason to keep anything on board unless it served an immediate and essential purpose.

Eric W. Sanderson and Marianne Brown, “Manahatta: An Ecological First Look at the Manhattan Landscape Prior to Henry Hudson,” Northeastern Naturalist 14, no. 4 (2007): 545–570. The confluence of the freshwaters of the Hudson River running from the north meeting the marine waters of the Atlantic Ocean, entering the harbor from the south in a classic tidal estuary, combined with a large number of creeks and extensive shallow subtidal flats to make for a perfect environment for the growth of oysters. For discussions of the oyster fishery, including subsequent declines, see: Peter J. Jacques, “The Origins of Coastal Ecological Decline and the Great Atlantic Oyster Collapse,” Political Geography 60 (2017): 154–164.; Clyde L. MacKenzie Jr., “History of the Fisheries of Raritan Bay, New York and New Jersey,” Marine Fisheries Review 52, no. 4 (1990): 1–44.; David R. Franz, “An Historical Perspective of Molluscs in Lower New York Harbor, with Emphasis on Oyster,” in Ecological Stress and the New York Bight: Science and Management, edited by Garry F. Mayer (Columbia, S.C.: Estuarine Research Foundation, 1982), pp. 181–197.

Bartlett Burleigh James and J. Franklin Jameson, ed., Journal of Jasper Danckaerts, 1679–1680 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913), p. 54. This practice almost certainly began with the Dutch in the earlier part of the seventeenth century and would have been well established by the time Danckaerts arrived.

Peter Kalm, “Travels in North America (1749),” in Selections from the Economic History of the United States, 1765-1860, edited by Guy Stevens Callender (Boston: Ginn and Co., 1909), pp. 16–20.

In 1784 two jars of New York pickled oysters cost fifteen shillings, which would be equivalent to about eighty dollars each in today’s money. Smith, “Josiah Harmar,” pp. 420–430.

Peter Kalm, Travels into North America (London: T. Lowndes, 1772), p. 186.

It has been suggested that the practice of pickling oysters began with fishermen at Saint-Michel-de-l’Herm in the Marais of Poitou. See: Marguelonne Toussaint-Samat, A History of Food (Chichester, West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 1992), p. 359. At a banquet given for James I in 1607 by the Guild of Merchant Taylors of the Fraternity of St. John the Baptist in the City of London, five barrels of pickled oysters were served; see Nancy Cox and Karin Dannehl, eds., Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities, 1550–1820 (Wolverhampton: University of Wolverhampton, 2007), accessed July 28, 2011, www.british-history.ac.uk/source.aspx?pubid=739. At the funeral feast of Thomas Sutton of the Charterhouse in 1612, three barrels of pickled oysters were served; see Walter Thornbury, “Ludgate Hill,” Old and New London, vol. 1 (London: Cassel, Petter & Galpin, 1878), pp. 220–233 (paragr. 54), https://www.british-history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol1/pp220-233. By 1637 there was a petition in England to prevent the export of oysters, both raw and pickled, in quart-sized barrels; see Calendar of State Papers Domestic: Charles I, vol. 366, August 18–31, 1637 (London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1868), p. 394, https://www.british-history.ac.uk/cal-state-papers/domestic/chas1/1637/pp377-400.

Hannah Glasse, The Art of Cookery, Made Plain and Easy (London, 1747), p. 269. Some period mentions refer to pickled oysters as “spiced oysters.” It is not clear if there is a distinction between those two preparations.

Martha Bradley, The British Housewife, or, The Cook, Housekeeper’s and Gardiner’s Companion (London: S. Crowder and H. Woodgate 1756), p. 76, https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_British_Housewife_Or_The_Cook_Housek/ckLZjgEACAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=nothing%20but%20stone.

In England, a standard measure for selling pickled oysters in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries was the hundred count or quart. Given that the Imperial quart is equivalent to 1136 ml, a single pickled oyster should be equivalent to approximately 11.4 ml. Note that this calculation uses the Imperial standard adopted in 1824 and not the Winchester Standards, which would actually apply here but are difficult to determine precisely. Hannah Woolley, A Gentlewoman’s Companion, or, A Guide to the Female Sex (London: A. Maxwell for Dorman Newman, 1673), https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A66844.0001.001/1:4.28.62?rgn=div3;submit=Go;subview=detail;type=simple;view=fulltext;q1=pickled. A pickled oyster recipe states: “put the liquor into Barrels, that will hold a quart or more, and when it is cold, put in the Oysters, and close up the head.”

The Diary of Samuel Pepys, Saturday 21 April 1660, accessed August 9, 2023, www.pepysdiary.com. Pepys was a naval administrator who was responsible in part for provisioning naval vessels, and it would have been in the best interest of the captain to treat Pepys well—in this case, he chose to share the pickled oysters and wine. British naval officers often came from coastal cities or the moneyed inland elite, both of whom were accustomed to eating fresh oysters whenever they chose to. With this motivation and the financial means to continue the habit, they would have purchased preserved oysters to take aboard ship.

“To George Washington from Captain John Barry, March, 9, 1778,” Washington Papers, Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-14-02-0080. Also, an account of the exchange appeared in the April 1, 1778, issue of the Connecticut Journal and describes how Captain Barry “got out most of the valuable articles” prior to burning the ship. The jar of pickled oysters was likely purchased by the British captain at George Forbes’ tavern at Whitehall Slip, in New York City, where naval launches landed. George was a Black man who catered to officers of the British services. In February 1778 Forbes was advertising the sale of “Pickled” and “fryed” oysters “put up in the best manner for either gentlemen of the navy or army”; see New-York Gazette, February 23, 1778.

“From George Washington to Captain John Barry, March 12, 1778,” Washington Papers, Founders Online, National Archives, Founders Online, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-14-02-0121.

This practice would have been well understood by British captains who were familiar with the East India Company, where private or “privilege” trade was allowed for captains, officers, and crew on a sliding scale of cargo space and value based on rank; see “East India Company Private Trade,” October 1, 2019, Untold lives blog, British Library, https://blogs.bl.uk/untoldlives/2019/10/east-india-company-private-trade-.html. For obvious reasons, these men tended to focus on items of high value and low volume—small jars of pickled oysters were both.

Dunlap’s American Daily Advertiser, March 16, 1791; City Gazette and Daily Advertiser, May 31, 1797.

During the seventeenth century wealthy planters in Barbados held lavish feasts for friends and visitors that often included a second course consisting of pickled oysters. This tradition continued well into the eighteenth century, and New York pickled oysters would have been a welcome addition to such feasts; see Samuel Clarke, A True and Faithful Account of the Four Chiefest Plantations of the English in America to Wit, of Virginia, New-England, Bermudus, Barbados (London, 1670), p. 66, Navigation Series, Early English Books Online, https://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A33345.0001.001/1:5.5?rgn=div2;view=fulltext. During the eighteenth century, letters between merchants, captains, and planters in the West Indies “read like communication between familiar friends . . . with the inquiries concerning the health of the recipient and his family, with announcements of sending of gifts and the extending of invitations, all couched in the terms of the utmost cordiality.” Herbert C. Bell, “The West Indian Trade before the Revolution,” American Historical Review 22, no. 2 (January 1917): 272–287.

Following the Revolutionary War, British navigation laws restricted the newly independent Americans from trading things like pickled oyster with the British sugar islands, which had been their primary market. By 1796 the Jay Treaty explicitly forbade the shipment of naval provisions, including pickled oysters, to the British sugar islands in American ships. Marketing small jars was one way to circumvent these trade restrictions.

Cox and Dannehl, eds., Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities, 1550–1820, accessed July 28, 2011, www.british-history.ac.uk/source.aspx?pubid=739. Based on the fact that a hundred oysters was equivalent to one quart, these jars, which held twenty-five oysters, would have been eight ounces (or a half pint) in size.

Surprisingly, the ceramic jars were used for the larger quantities of oysters. See the advertisement for Abraham Delanoy from Manhattan dated 1774 for an example of this practice in New York: Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, June 16, 1774.

“OYSTERS.—J. Sommervail begs leave to inform his friends and the public, that he has now on sale for ready money only, OYSTERS, cured in a peculiar manner, and of a superior quality, for Lunches, Sauces, &c. &c. They are considered by all who have tasted them as a great delicacy. To be had in Jars, from 2s.6d. and upwards, with his name thereon, Orders addressed to No. 15, St. Swithin’s-Lane, Lombard-street, will be punctually attended to, and sent to any part of the town, or to country conveyances, free of expence. N.B. They are particularly adapted for exportation to hot climates, and for sea stores, &c. but timely notice should be given for such orders. Those who take quantities will be liberally dealt with”: Morning Herald, September 19, 1806.

See Meta F. Janowitz, “New York City Stonewares from the African American Burial Ground,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2008), pp. 5–9, for a history of the Crolius and Remmey family potteries in Manhattan.

There is little doubt that ceramic containers would have been more hygienic than porous and leaky wooden kegs, but it is not clear if this was ever considered by the oystermen. With regard to the relative labor required to produce a ceramic versus a wooden vessel of a quart size, a cooper and expert in colonial mechanical arts stated: “Ceramics would be cheaper and much more practical. Hand-made, such a keg would take a couple of hours”: Tom Kelleher, Historian and Curator of Mechanical Arts, Old Sturbridge Village, e-mail to the author, July 1, 2023.

Olive R. Jones, “Commercial Foods, 1740-1820,” Historical Archeology 27, no. 2 (1993): 25–41.

Despite the fact that they were made of highly resilient stoneware, these jars would have been equivalent to our modern-day soda cans. A distinction should be made between the early type and those produced after the 1820s. The later ones would have been reuseable given the larger openings; however, the fact that these too were opened mostly at sea meant that they also would have been disposable.

Personal communication with Charles Dagneau, Underwater Archaeologist, Parks Canada, and Aimie Néron, “Les grès du Machault (1760)” (unpublished manuscript, Parks Canada, 2014). A fragment of one of these jars was analyzed using pXRF (see note 42). By comparing known samples from New York, Germany, and England, it was determined that there was a high probability that these jars were made in New York based on the levels of yttrium in the clay.

We can’t be certain that the wooden kegs were indeed the same size as the ceramic jars, since it may have just been convenient to show these as the same size for the sake of the layout of the advertisement. As noted previously, only wooden kegs would be appropriate for packing volumes greater than one gallon, and there is every indication that wooden kegs holding four or five gallons of pickled oysters continued to be used in New York for shipping abroad. It is not clear why Delanoy chose to enhance his advertisement with the prominent woodcut image of the oyster jar and keg, but his graphic was the only one on the page of the newspaper where his ad appears and one of only two in the entire newspaper, making his ad clearly stand out.

See Janowitz, “New York City Stonewares,” pp. 5–9.

Clarkson Crolius Price List, about 1810, illustrated in Zipp, Commeraw’s Stoneware, p. 113.

New York Gazette and the Weekly Mercury, March 22, 1773. I can find no evidence that Durell produced oyster jars while in Philadelphia, and I believe he only started to make this form once he arrived in New York and became aware of the demand.

See Hume, “Cap-Hole Oyster Jars,” pp. 150–164. Hume theorized that small ceramic caps were used to seal Commeraw’s jars, but no such caps have been discovered. In his defense, he was making an assumption based on a sample size of three or four jars that were available to him, and all of these did in fact have a suitably recessed gallery. However, based on handling over thirty jars and viewing pictures of another thirty-plus, I have determined that gallery depth was not consistent, and in many cases non-existent. In truth, for most jars I have observed, it would not be possible to utilize anything other than a cork or wooden bung to seal the openings. In fact, some of the inner lip of the openings is flush with or even projecting slightly above the tops of the jars.

General Advertiser, December 8, 1774; Daily Advertiser, December 7, 1786; Daily Advertiser, April 21, 1788.

See Hume, “Cap-Hole Oyster Jars,” and Zipp, Commeraw’s Stoneware, pp. 149–168.

The large Commeraw jar pictured in figure 1 holds 2352 ml, which is equivalent to approximately 208 oysters. This amount of oysters would have been more than one individual would normally eat and was more suited to a small gathering. The small jars pictured in figure 1 would have held between thirty and fifty oysters.

It is not possible to compare directly the costs of a ceramic versus a wooden vessel during this period, but based on the ease and speed of creating the ceramic form it is hard to imagine that a wooden vessel could compete in price. Regardless of size, producing a wooden keg requires assembling at least ten individually hand-shaped components, including two heads, six or more staves, and at least three wooden bands. In addition to this, the stoneware jars were better suited to holding liquid and could be stamped with the name of the oysterman during production, obviating the need for other markings.

Considerable evidence suggests that all but one of the known oyster jars produced for Thomas Downing were made in Norwalk, Connecticut. In discussing the production of Asa Smith’s Norwalk pottery during the years 1825–1837 Watkins notes: “oyster jars differed from preserve jars in having a sharp rather than a round shoulder.” She went on to write that “tomato jars, or ‘corkers’ were the forerunners of the modern preserve jars. They had narrow necks for the insertion of cork stoppers.” The corkers she was referring to have the rounded shoulder with an opening the same size as the oyster jars; see Lura Woodside Watkins, Early New England Potters and Their Wares (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1950), p. 204, https://whatelyhistorical.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/earlynewenglandpotters.pdf.

Scott appears to have worked his way up from an oysterman to a pickler and merchant of significant standing. Among his credits in the oyster industry are his discovery of the Saddle Rock oyster in Little Neck Bay, New York, in 1827, which became the most popular oysters in New York for a time. “Saddle Rocks were first brought to Fulton Market, New York, by an old negro named Henry Scott”: Inter Ocean Chicago, October 31, 1874, p. 6. By 1851 he was a highly successful businessman, and it was noted that he was in business for more than twenty years by that time and “His business is principally confined to supplying vessels with articles and provisions in his line of business, which in this great metropolis is very great . . . there are doubtless been many a purser, who cashed and filed in his office the bill of Henry Scott, without ever dreaming of his being a colored man.” Scott was described as a mulatto in the Dun credit report, where he is noted as being “very honest” and “very responsible,” among other qualities: Juliet E. K. Walker, The History of Black Business in America: Capitalism, Race, Entrepreneurship, vol. 1, To 1865 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), p. 145.

These jars share common characteristics, including a consistent light gray body color and quality of throwing, with several jars pictured in John E. Kille, “Distinguishing Marks and Flowering Designs: Baltimore’s Utilitarian Stoneware Industry,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2005), pp. 93–132. This type is different from the early New York jars produced by Commeraw and others, where the color, size, shape, and gallery details varied considerably within and among potters.

While I don’t believe that jarred pickled oysters would have been as much a trade item offered by ship captains by this late date, these jars were likely packed into the hold of a clipper ship sailing from Baltimore to the West Coast since the transcontinental railroad was not completed until the 1860s.

See Nicolas Appert, The Art of Preserving All Kinds of Animal and Vegetable Substances for Several Years, A Work Published by Order of the French Minister of the Interior on the Report of the Board of Arts and Manufactures, 2nd ed. (London: Black, Perry and Kingsbury, 1812), p. 164. Appert introduced the canning process, which brought about the metal cans that would come to dominate the packing of oysters in Baltimore and elsewhere.

In an attempt to attribute unmarked oyster jars that previously had been attributed to Commeraw based on appearance alone, I teamed with Clara Chang, a graduate student in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Columbia Climate School, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, in Palisades, New York. Chang is an expert in pXRF use and is a student of Dr. Dorothy M. Peteet, Senior Research Scientist at NASA/Goddard Institute for Space Studies and adjunct professor, Columbia University. This analysis began with a group of marked Commeraw jars and fragments to establish the range of elemental composition in Commeraw’s wares. In addition to this, other marked stonewares from Manhattan and elsewhere were used to create a database. As of this writing, the analysis is still being refined, but preliminary results and Chang’s analysis seem to indicate that it will be possible to trace those jars made with clay originating in the Hudson River watershed.

This relates mostly to the unusually small opening size, which would prevent refilling with anything but thin liquids; given the small size and often thick walls, the jars might only hold a pint. In addition to this, the top of the jars was turned in such a way that the bottom inside of the opening was lower than the inner walls of the upper shoulder, which would cause a small amount of liquid to remain in the jars even when turned upside down unless shaken repeatedly.

G. J. Marcus, Heart of Oak: A Survey of British Seapower in the Georgian Era (Oxford and London: Oxford University Press, 1975), pp. 308, 101.

See: “Stoneware Oyster Jar,” before 1816, no. 18-169, Nan A. Rothschild Research Center, NYC Archaeological Repository, New York, N.Y, https://archaeology.cityofnewyork.us/collection/search/south-street-seaport-209662-stoneware-oyster-jar.

Trade between New York and Demerarra began in the late eighteenth century, facilitated by the construction of the “American stelling,” or pier, where American ships discharged and loaded their goods. The British reoccupation of the port in 1803, which timing coincides nicely with the period during which Commeraw was making the marked jars for Daniel Johnson—between 1799 and 1805 based on the Lumber Street address used on the jars—may have also allowed for increased trade between New York and this area.

A series of jars made for Daniel Johnson has been recovered in Guyana, including jars that have different imprints on them that include his full name spelled out, an abbreviated version, and one that implies a partnership signified by “& Co.” It doesn’t seem likely that these jars would have been produced at the same time; therefore, they were probably not filled and shipped during the same period.

Raymond Beecher, “Thomas T. Thomson—Pinckney’s Enigma,” Quarterly Journal, A Publication of the Greene County Historical Society, Inc. 4, no. 3 (fall 1980): 1–5.

Essequebo and Demerary Gazette, August 25, 1804.