Oyster jar, Thomas Commeraw, New York, New York, 1799–1804. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/4". (Unless otherwise noted, all objects from the author’s collection; photo, Rory MacNish.) This oyster jar, marked “DANIEL | JOHNSON.AND.CO NO. 24 | LUMBER STREET | NEW.YORK,” is surrounded by large live New York oysters and a period cast iron oyster knife. Found in Guyana, the jar has the less common “NEW.YORK” imprint rather than the more typical “N.YORK.”

Oyster jars, attributed to Thomas Commeraw, New York, New York, 1797–1805. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. (of tallest) 8 7/8". (Photo, Christopher Pickerell.) The tall jar at center was recovered by a diver off the island of St. Croix. The other jars were all found in coastal Guyana. The jar at far right is pictured in detail in figure 1; the jar second from right is an unmarked example that is identical in size, glaze, and gallery details to a Commeraw jar made for New York oysterman George White in the author’s collection. The two Daniel Johnson jars on the left appear to have been made by the same hand given the identical impressions and similar gallery details. The differences in color and texture are likely due to varying conditions in the kiln during firing (i.e., oxidation and reduction).

Oyster jars, various makers, 1774–1850. Albany-slipped and salt-glazed stoneware. H. (of tallest) 9". The earliest example is shown second row far left, recovered in Guyana. The pieces shown in the two front rows and the large Albany slip-glazed collared example in the back row were likely produced for the New York market. The smaller dark brown glazed collared example, second row far right, was recovered in Hamilton Harbor, Bermuda, and the orange-brown example, front row far right, was recovered in St. Georges Harbor, Bermuda. The three salt-glazed examples in the back row were made for the Baltimore market. The examples on the ends are both marked “E.DERLIN” and made for Edward Derling, a white man who ran an “oyster house” on Caroline Street south of Bank St. in 1835-36.

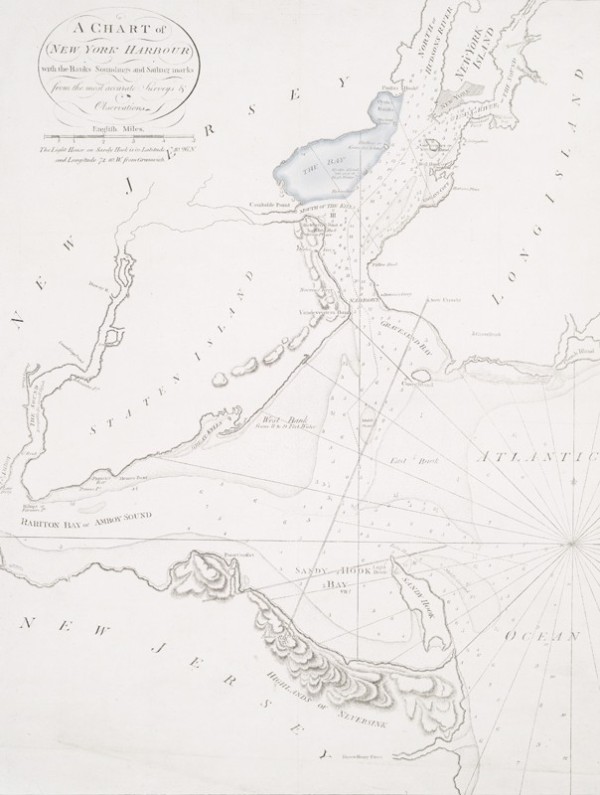

Jno. Mount and Tho. Page, A Chart of New York Harbour, with the Banks Soundings and Sailing Marks from the Most Accurate Survey & Observations. (London, 1794), paper, 24" x 18". (Courtesy, New York Public Library.) New York Harbor as it appeared in the third quarter of the eighteenth century. Note the area designated as “Oyster banks” due west of the southern tip of Manhattan, just south of Paulus Hook, New Jersey. The area denoted in light blue on the map, from Paulus Hook south along the Bayonne shoreline, represents the primary oyster grounds of the early fisheries.

Pickled oysters prepared by the author using a modern adaption of a traditional recipe. Jarred oysters would have been poured onto a dish or into a bowl to eat. These large oysters were the preferred size for pickling compared to the much smaller cocktail-sized oysters served on the half shell today. (Photo, Christopher Pickerell.)

Oyster jar, London, England, ca. 1806. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. approx. 5 1/2". (Private collection.) This small jar marked “Sommervail’s Oysters” was found in London. Despite the fact that Sommervail listed the sale of several sizes of jars in his advertisements, this is the only marked example known to the author.

Oyster jar, probably New York, New York, 1759–1760. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Parks Canada; photo, Karolyn Gauvin.) This is one of six oyster jars recovered from the hold of the French frigate Machault, which sank in the Restigouche River during a battle with the British in 1760.

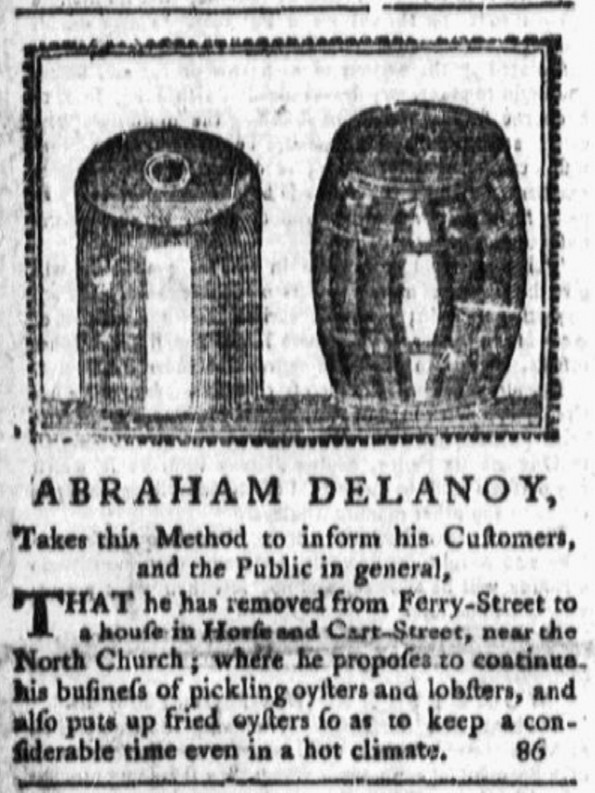

Advertisement for Abraham Delanoy in Rivington’s New-York Gazetteer, June 16, 1774. This woodcut printed image of the jar and keg was used by Delanoy sporadically in this newspaper from June 16, 1774, until December 13, 1775. (Readex, America’s Historical Newspapers.)

Re-creation of Abraham Delanoy’s advertisement in figure 8. Note that the keg pictured here is a later version with metal hoops, while a keg from the 1774–1775 period would have been made with wooden hoops.

Oyster jars, New York, New York, 1780–1800. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. (of tallest) 6 1/2". Included in this group of early oyster jars are at least two (back row far left and far right) that have been attributed to Thomas Commeraw. Note how the inner rim of several of the openings of these jars is flush or nearly flush with the shoulder, while the others are so shallow as to preclude the use of anything other than a cork to seal them. These slightly recessed galleries would have helped to retain the wax or pitch used to seal the cork.

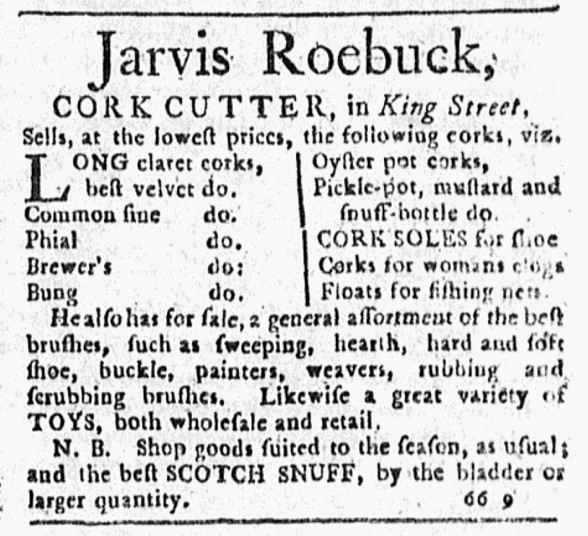

Advertisement listing “Oyster pot corks” placed by Jarvis Roebuck, General Advertiser, December 8, 1774. (Readex, America’s Historical Newspapers.)

Mark Shapiro turning a Thomas Commeraw-type oyster jar at his studio, Stonepool Pottery, Worthington, Massachusetts, on June 14, 2022. (Photo, Christopher Pickerell.)

Oyster jars, probably Connecticut, 1830–1845. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. (left) 6 1/2", H. (right) 6". The jar on the right is stamped “HENRY SCOTT | 217 WATER STREET | NEW YORK.” The distinctive lettering on the Scott jar matches that on most of the Thomas Downing jars and is identical to that found on two jugs produced in Norwalk, Connecticut, thus pointing to a Connecticut manufacture for these examples.

Oyster jars, probably Alexandria, Virginia, ca. 1850. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. (of tallest) 8 1/2". These jars were almost certainly produced by an Alexandria potter for the Baltimore or Alexandria market. They were recovered together in a Sacramento, California, hotel privy in a circa 1850 context.

Finds map for seventy of the eighty-five surviving jars known to the author. This information is based on data gathered from divers, bottle diggers, auction records, archaeological reports, and private collectors.

Detail of the base of a Commeraw-type oyster jar recovered by Teddy Tucker in Bermuda. (Courtesy, Wendy Tucker; photo, Christopher Pickerell.) Note the marks made by the feeding activity of a parrotfish.