Face vessel, Greek culture, ca. 480–430 BCE. Painted terracotta. H. 3 5/8". (Courtesy, Walters Art Museum.) Aryballos in the form of the head of an African.

Egyptian god Bes jar, Late Period, 5th century BCE. Painted terracotta. H. 7 1/4". (Courtesy, Egyptian Museum, Turin. Drovetti Collection, cat 2553.)

Beaker, Roman culture, Naples, Italy, 1st century CE. Unglazed earthenware. H. 3 3/4". (Courtesy, British Museum, G_1859-0716-1.)

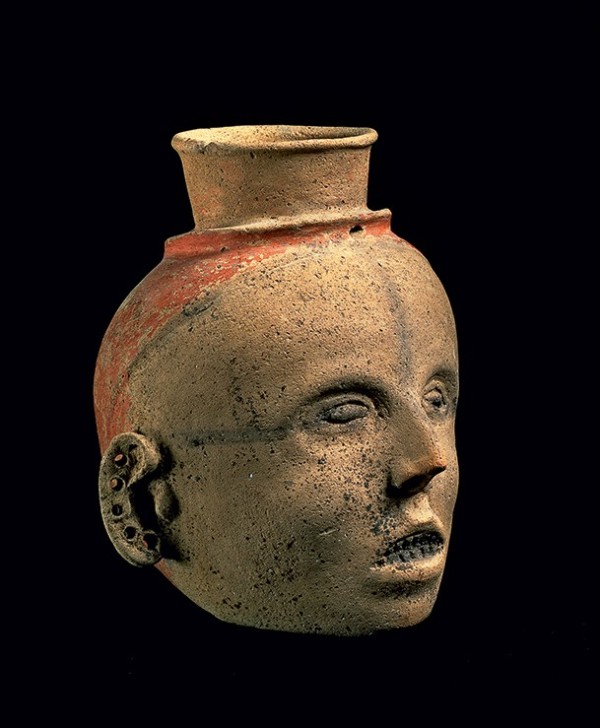

Portrait bottle, Moche culture, Peru, 3rd–6th century. Painted earthenware. H. 8 3/8". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art; gift of Nathan Cummings, 1967, Accession Number: 67.167.2.) https://www. metmuseum.org/art/collection/ search/309490.

Human head effigy vessel, Oneota culture, Arkansas, 1550–1650. Low-fired earthenware with red and black pigments. H. 7 3/4". (Courtesy, Fenimore Art Museum, gift of Eugene V. and Clare E. Thaw Charitable Trust; photo, John Bigelow Taylor, NYC.)

Anthropomorphic vessel, Kingston type, London area, England, 13th century. Green-glazed earthenware. Height not provided. (Courtesy, Herbert Art Gallery and Museum.) https://www. coventrycollections.org/search/details/ collect/93782.

Bartmann bottle, Frechen, Germany, ca. 1620. Salt-glazed stoneware, iron oxide wash and cobalt slip highlights. H. 10 1/4". (Courtesy, Collection of Joseph P. Gromacki; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Bartmann bottles, Frechen, Germany, ca. 1600–1610. Saltglazed stoneware, iron oxide wash. (Courtesy, Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.) Archaeologically recovered examples from Jamestown, Virginia.

Face pitcher, probably Staffordshire, England, ca. 1795–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10 1/8". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Toby jug, Staffordshire, England, ca. 1785–1810. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

Face pitcher, attributed to Charles Bloodworth, Lambeth Pottery, London, England, ca. 1800. Salt-glazed stoneware with iron oxide wash. H. 7". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Face vessel, attributed to Jonathan Fenton pottery, Dorset or East Dorset, Vermont, ca. 1810–1827. Slip-glazed stoneware. H. 7 7/8". (Courtesy and © San Diego Museum of Art / Gift of Mrs Leon J. Rose, Jr. / Bridgeman Images.)

Detail of the “JFenton” mark on the face vessel illustrated in figure 12.

Jug, Jonathan Fenton, Dorset, Vermont, ca. 1800–1810. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 11 3/4". (Courtesy, Crocker Farm, Inc.)

Face jug, unidentified artist, Northeastern U.S., 1820–1850. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 6". (Courtesy, Crocker Farm, Inc.)

Face jug, Northeastern U.S., ca. 1820–1850. Stoneware with kaolin and manganese glaze. H. 11 3/4". (Courtesy, Fenimore Art Museum, Cooperstown, N.Y., Museum purchase, N0225.1951.)

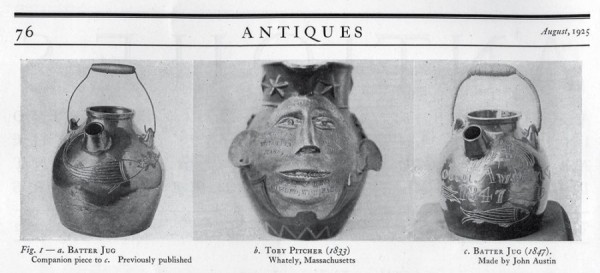

Illustration from “A Strange Face from Whately,” Antiques 8, no. 2 (August 1925): 76.

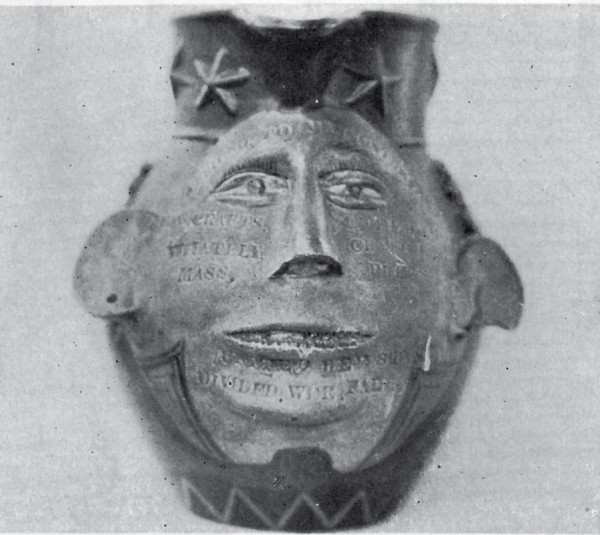

Detail of the “Toby Pitcher” illustrated in figure 17. Across the forehead in impressed printers type runs the legend “A. Friend. ‘to. My. Countrey.” On the left cheek is “E. G. Crafts, Whately Mass”. On the right cheek is “O’ The. Dimocratick. Press.”, and across the lower lip is “United Wee Stand, Divided, Wee, Fall.”

“Grotesque jug from Whately, Massachusetts,” illustrated in John Spargo, Early American Pottery and China (Garden City, N.Y.: Garden City Publishing, 1926), p. 121. These side and back views show the detail of the applied thistle, rose, and shamrocks. The date of 1833 in gilt is on the back below the handle.

Storage jar, Barnabas Edmands, Charlestown, Massachusetts, 1833. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 15 1/8". (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; photo, Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.) Beneath the applied molded eagle is “Genl Andrew Jackson”; the reverse is inscribed with “17th June 1775,” the date of the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Pitcher, Martin Crafts, Nashua, New Hampshire, ca. 1838. Stoneware with slip glaze. H. 9". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) Impressed with printers type on the bottom front is “T. CRAFTS & CO. | NASHUA” and above the eyes, “SLOOP ORANGE”.

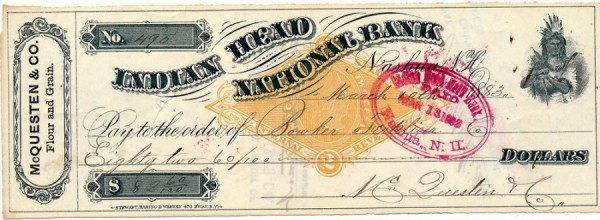

Bank check, Indian Head National Bank, Nashua, New Hampshire, dated March 10, 1883. Printed by Stewart, Haring and Warren of New York. Engraving on paper. L. 8". (Private collection.) Note the inclusion of an image of a Native American Indian.

Detail of the engraved Native American pictured on the bank check illustrated in figure 22.

Side view of the pitcher illustrated in figure 21 showing the linear use of slip to create the appearance of Native American face paint decoration.

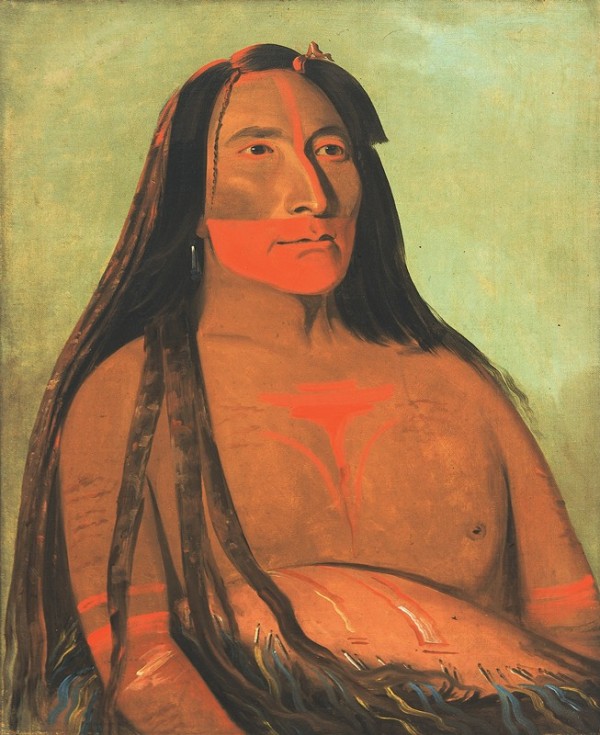

George Catlin, Máh-to-tóh-pa, Four Bears, Second Chief in Mourning, 1832. Oil on canvas. 29 x 24". (Courtesy, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr., 1985.66.13.) Note the use of paint around the lower part of the face.

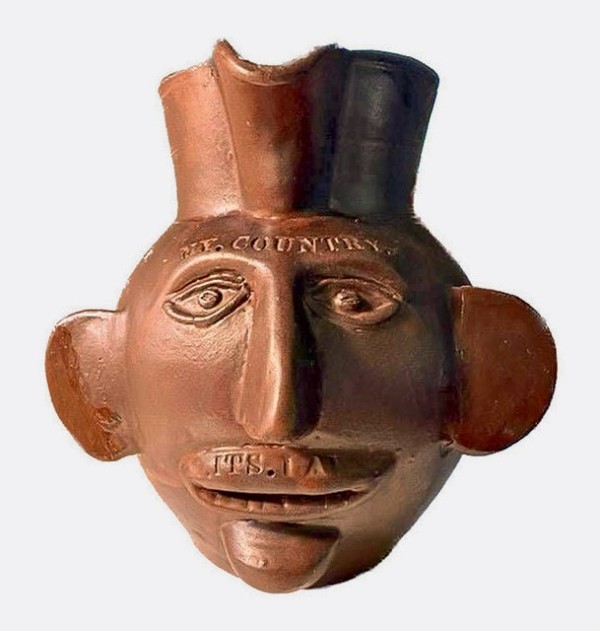

Pitcher, Martin Crafts, Nashua, New Hampshire, ca. 1839. Stoneware with slip glaze. H. 7". (Private collection; photo, George Browning.) Impressed on the forehead: “MY COUNTRY”; on the upper lip: “ITS LAWS”; on the left side of the jug: “CHARLES KEMP”; and on the right side: “NASHUA.”

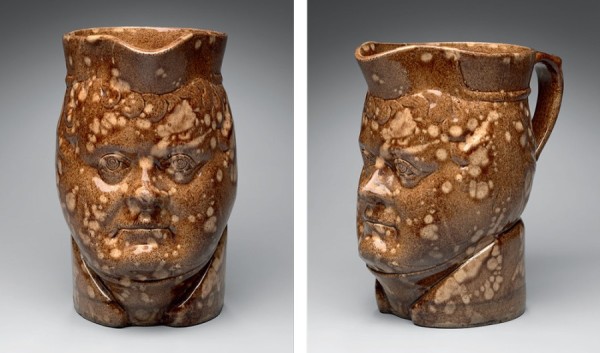

Toussaint Louverture face pitcher, Medford, Massachusetts, ca. 1840. Earthenware with Albany slip glaze. H. 13". (Chipstone Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.)

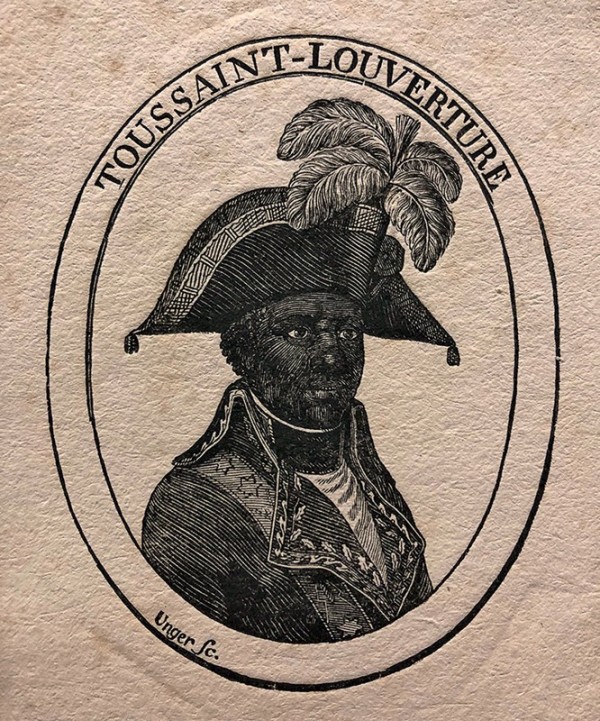

Johann Friedrich Unger, portrait of François-Dominique Toussaint Louverture, 1790–1804. Engraving on wove paper. 3 3/8 x 2 11/16" (plate). (Courtesy, RISD Museum; Gift of Isaac C. Bates.) https://risdmuseum.org/art-design/ collection/portrait-francois-dominiquetoussaint-louverture-9303884#content__ section—use--948621.

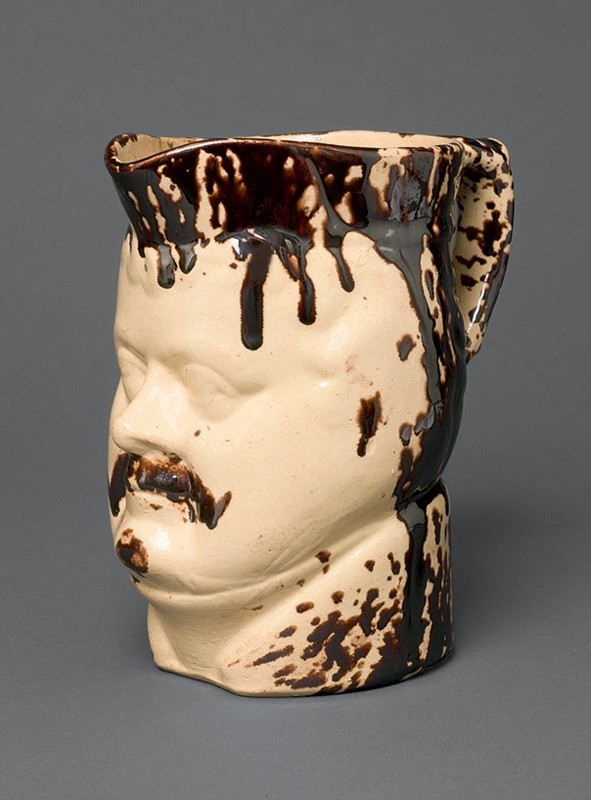

Face pitcher depicting Daniel O’Connell, Ralph Bagnall Beech, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1848. Earthenware with Rockingham glaze. H. 7 1/2". (Courtesy, Yale University Art Gallery, Mabel Brady Garvan Collection, 1931.1816.)

William Say, Daniel O’Connell, probably after James Arthur O’Connor, circa 1803–1834. Mezzotint. 8 3/4 x 7 1/4". (Courtesy and © National Portrait Gallery, London.)

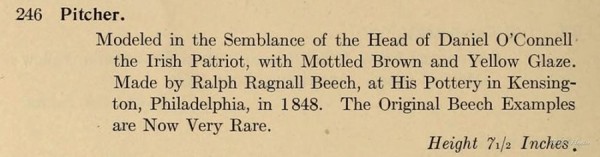

Auction Lot 246 from Edwin Atlee Barber, Illustrated Catalogue of China, Pottery, Porcelains and Glass (Philadelphia: W. H. Pile’s Sons), 1917. (Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Digital Library.)

Face pitcher depicting Daniel O’Connell, Thomas Haig’s Pottery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1891. Rockingham glazed yellow ware. H. 7 1/16". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with Museum funds, 1896.)

Illustration of a Remmey face pitcher published in Warren E. Cox, The Book of Pottery and Porcelain, 2 vols. (New York: Crown Publishers, 1970), 2: 986.

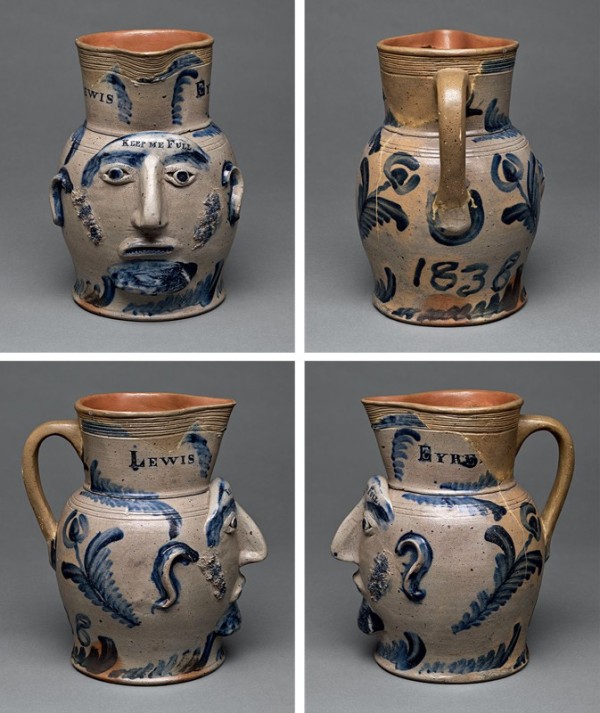

Pitcher, attributed to Henry Remmey Jr. and Richard C. Remmey, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, dated 1838. Salt-glazed stoneware with cobalt oxide. H. 8 1/2". (Courtesy, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Gift of Mrs. Arnold Miles of Washington, DC, 1952.) Marked with impressed printers type reading “LEWIS EYRE”, “KEEP ME FULL”, and “1838”. The accession record for this pitcher states: “Found in old house on Schooley Mill property, Tucker Lane, near Ashton, Howard County, Maryland. Lewis Eyre owned the adjacent property, was also a resident of Philadelphia.”

Face vessel, attributed to Henry Remmey Jr. and Richard C. Remmey, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1840–1850. Salt-glazed stoneware with cobalt oxide. H. 6 13/16“. (Courtesy, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Gift of Preston R. Bassett from Ridgefield, Conn., 1979.)

Face jug, attributed to the Thorn Pottery, Crosswicks, New Jersey, dated 1844. Lead-glazed earthenware with manganese oxides. H. 6 1/2". Incised with the date: Oct. 5 | 1844. (Courtesy, Crocker Farm, Inc.) Kaolin has been applied in a thin veneer or as a slip to create the contrasting color of the eyes and teeth.

Face cup, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1850–1860. Alkalineglazed stoneware with kaolin details. H. 4 7/8". (Courtesy, Collection of William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Face cup, possibly Thomas Davies Factory, Bath, South Carolina, ca. 1861–1864. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with kaolin details. H. 4 7/8". (Courtesy, Collection of Joseph P. Gromacki; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of the collector’s label on the bottom of the face cup illustrated in figure 38. “Made in Africa | Presented to T H B. | by | Horace J. Smith | of Phila | Pa.”

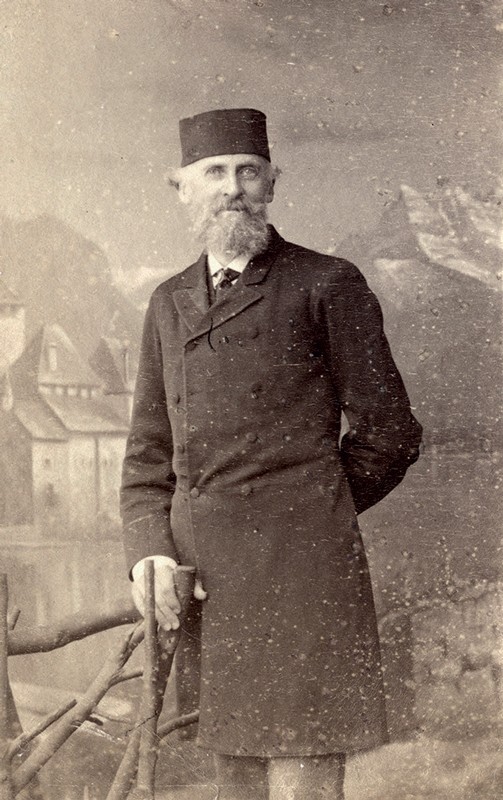

Portrait of Horace J. Smith by an unknown photographer, London, England, 1889. Albumen print on card. 3 5/8 x 2 1/4". (Courtesy and © National Portrait Gallery, London.)

Portrait of Martha Schofield by an unknown photographer. Back of photograph reads: Martha Schofield 1883. 7 x 5" (Courtesy, Martha Schofield Papers, Martha Schofield photograph collection, SFHL-PA-143, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, A00183921.) https://digitalcollections.tricolib. brynmawr.edu/object/sc178831

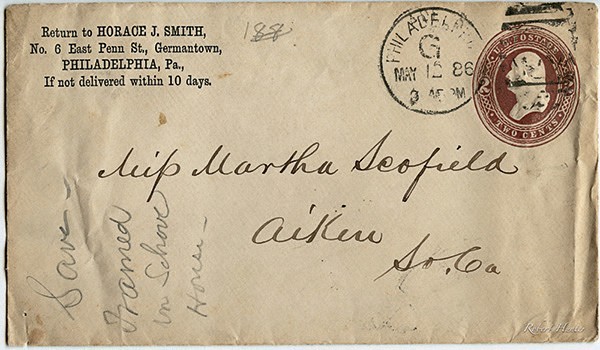

Envelope sent to “Miss Martha Scofield [sic]” by Horace J. Smith, May 18, 1886. (Courtesy, Martha Schofield Papers, SFHL-RG5-134, Friends Historical Library of Swarthmore College, A00183217.)

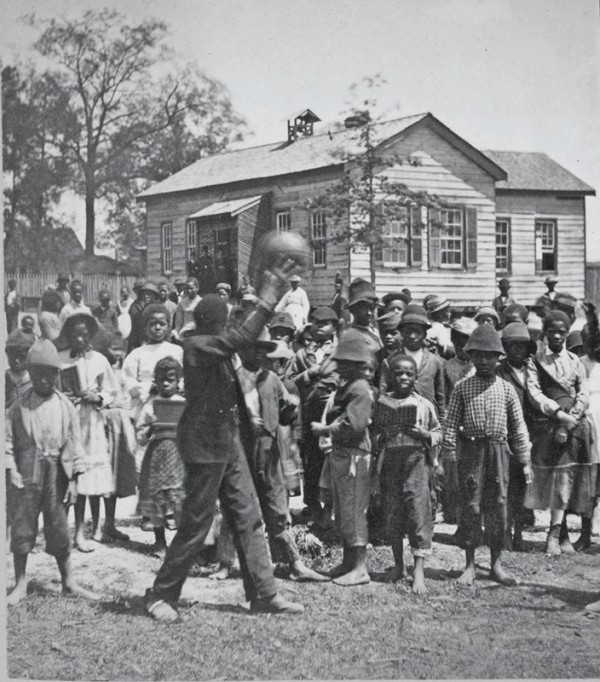

James. A. Palmer, Colored School; from the series: Aiken and Vicinity, 1882. Stereopticon photographic print. 3 1/2 x 7". (Courtesy, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. “Colored School,” New York Public Library Digital Collections.)

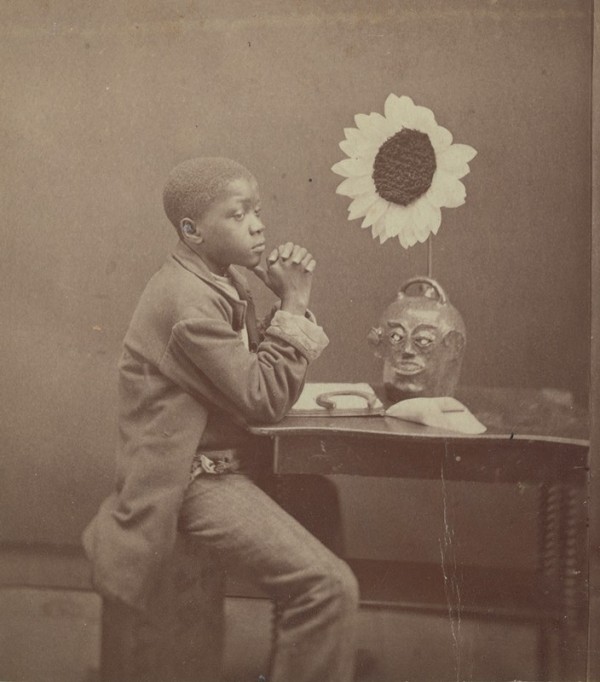

James A. Palmer, An Aesthetic Darkey; from the series: Aiken and Vicinity, 1882. Stereopticon photographic print. 3 1/2 x 7". (Courtesy, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Nancy Dunn Revocable Trust Gift, 2017, 2017.311.)

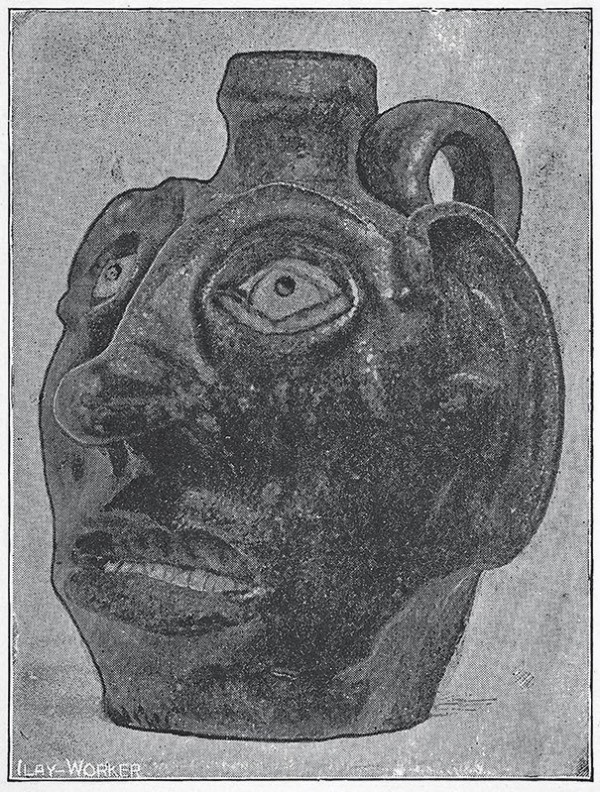

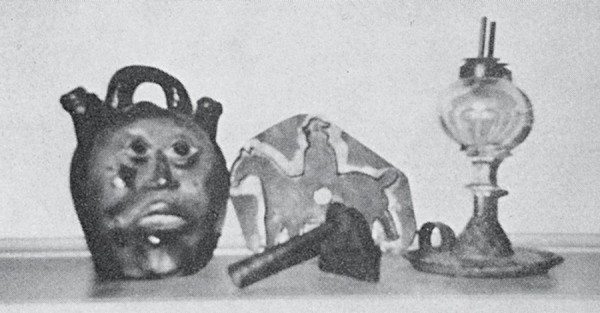

Photograph of a “Monkey Jug” published in Edwin Atlee Barber, The Pottery and Porcelain of the United States (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1909), p. 466. The image was first published in “Some Curious Old Water Coolers Made in America,” Clay-Worker 33, no. 5 (1900): 353.

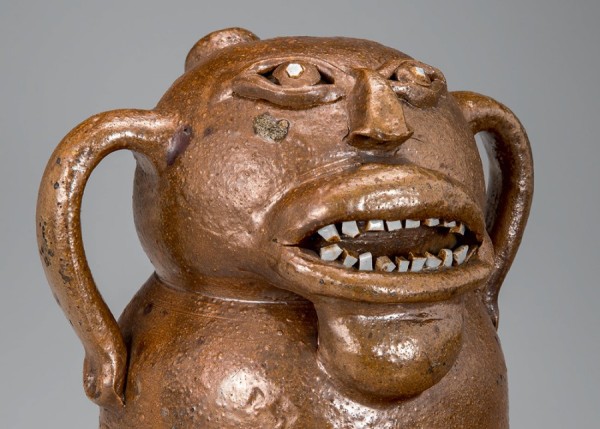

Face jug, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1850–1860. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with kaolin inserts. H. 6 1/2". (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.) This example is virtually identical to the one illustrated by Barber in figure 45.

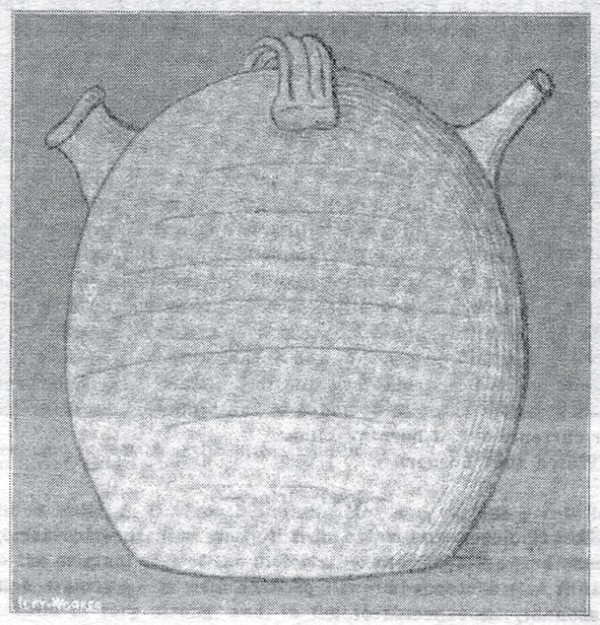

Illustration of an “Earthen ‘Water Monkey’” published in Edwin Atlee Barber, “Some Curious Old Water Coolers Made in America,” Clay-Worker 33, no. 5 (1900): 353.

Face jug, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1850–1860. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with kaolin inserts. H. 7". (Courtesy, Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of Frank Samuel, 1917–196.)

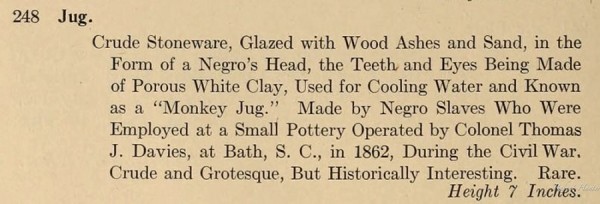

Auction Lot 248 from Edwin Atlee Barber, Illustrated Catalogue of China, Pottery, Porcelain and Glass (Philadelphia: W. H. Pile’s Sons), 1917. (Smithsonian Libraries and Archives Digital Library.) This entry describes the jug illustrated in figure 48 as a “Monkey Jug.” Note the use of the descriptive terms “Crude and Grotesque” as well.

Botijo, Spain, 20th century. Unglazed earthenware. H. 13 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Seth Eastman, Osceola in Captivity, Florida, ca. 1837. Oil on canvas. Dimensions unknown. (Bridgeman Images/private collection.)

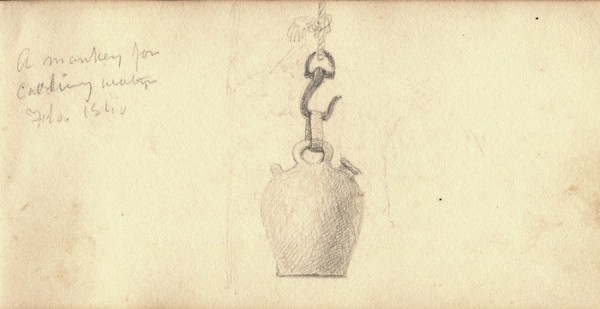

Seth Eastman, “A monkey for cooling water Feb, 1840.” Pencil on paper. 3 3/8" x 6 3/4". (Courtesy, Hennepin County Library Special Collections, Minneapolis Central Library.)

“Monkey jug,” attributed to Washington County or Crawford County, Georgia, ca. 1860. Stoneware H. 10". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) The jug has the classic two spouts and a strap handle over the top, with a finial that is seen on early examples.

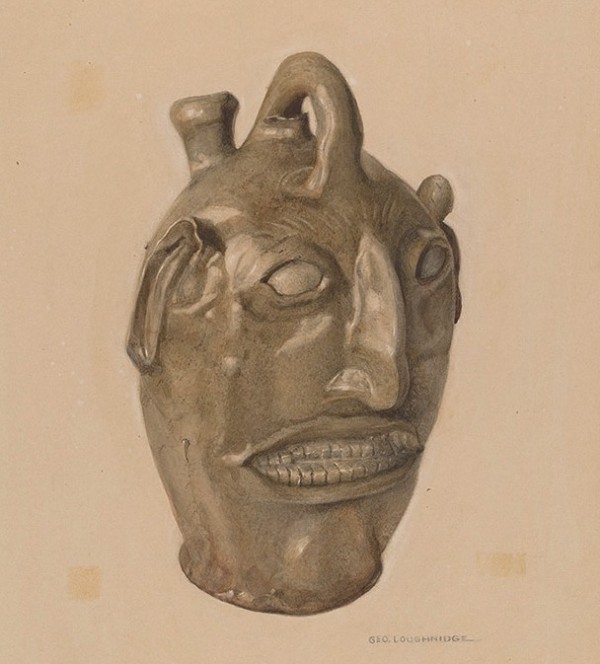

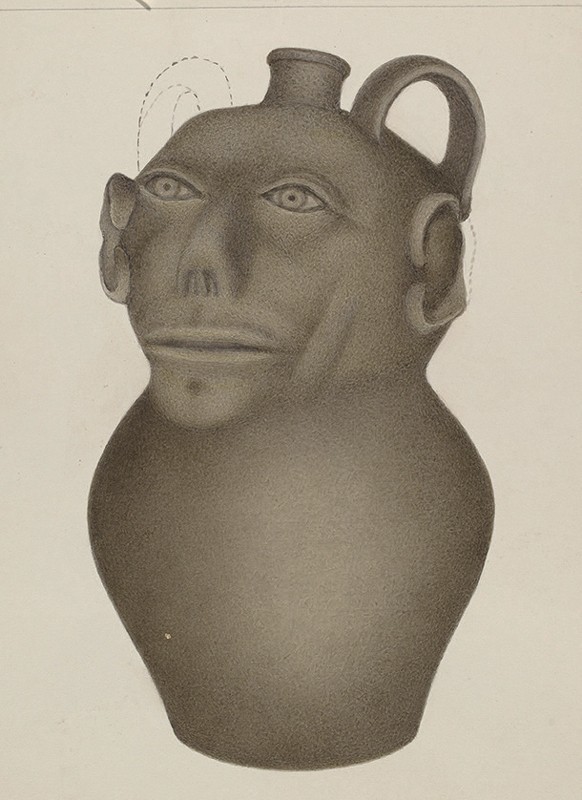

George Loughridge, Grotesque Jug, ca. 1938. Watercolor, graphite, and colored pencil on paperboard. 17 x 14 15/16“ (original IAD Object: H. 8 3/4"). (Courtesy, National Gallery of Art Index of American Design, 1943.8.7451.)

Face jug, Thomas Chandler, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1850. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 11". (Private collection; photo, McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina.)

Face vessel, possibly Thomas Chandler, Edgefield County, South Carolina, ca. 1840–1845. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with iron oxide slip. H. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) Inscribed: “John Bull, Esqr” and “Long” on the reverse. The stirrup handle has been broken off.

Face jug, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1850–1860. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with kaolin details. H. 11". (Courtesy, Collection of Joseph P. Gromacki; photo, Robert Hunter.) A somewhat unique and visually distinctive example of the Southern face vessel.

Face jug, Edgefield, South Carolina, ca. 1850–1860. Alkaline-glazed stoneware with kaolin details. H. 11". (Private collection; photos, Joe Wittkop.) Marked with incised script on back: “Dick Abney”. This may be the most powerfully sculpted of all the Edgefield face vessels, featuring dark brown glaze with stark kaolin eyes.

Face vessel, attributed to John Wesley, Columbia, Pennsylvania, ca. 1870. Lead-glazed earthenware. H. 10 1/8". (Courtesy, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) Note the use of kaolin as a slip to create a veneer for the eyes, and possibly the teeth.

Photograph in Pennypacker’s auctioneering brochure, The Private Collection of Robert R. & Joanne Dreibelbis, Monday, May 17th, 1993 (Courtesy, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.) Shown is a face jug listed as a “Rare double spout face jug signed John Westley, 1870.”

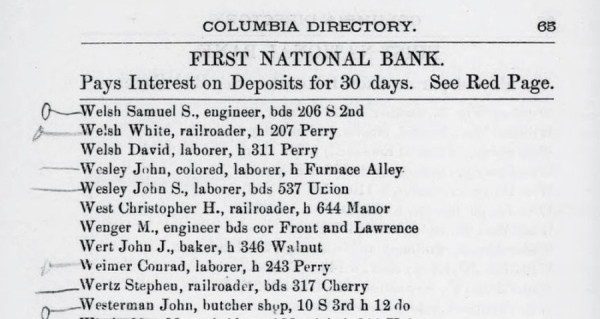

Young’s Directory of Columbia (Columbia, Pa.: Grier and Moderwell, 1874), p. 65. John Wesley is listed as a “colored, laborer” residing in Furnace Alley.

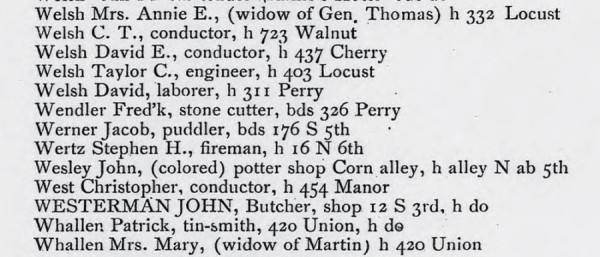

Young’s Directory of Columbia (Columbia, Pa.: Young and Hook Publishers, 1878), p. 53. “Wesley, John, (colored) potter shop Corn alley, h alley N ab 5th.”

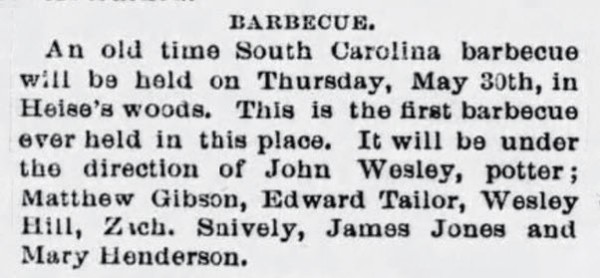

“Barbeque,” Intelligencer Journal (Lancaster, Pa.), May 10, May 1878, page 3.

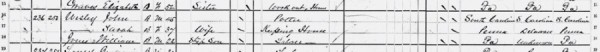

1880 U.S. Federal Census, Lancaster, Columbia, Pennsylvania, p. 24, enumeration district (ED) 128, sheet 10B, dwelling 236, family 250, entry for John Wesley, Columbia, Pennsylvania, as a Black male, age 45, occupation potter, and listing his birthplace and that of his parents as South Carolina.

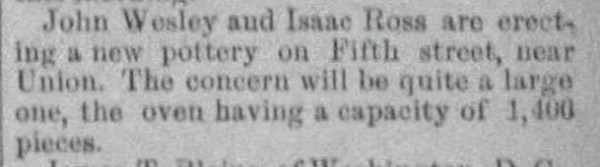

Excerpt from “Notes,” Lancaster New Era (Lancaster, Pennsylvania), April 14, 1892, p. 1.

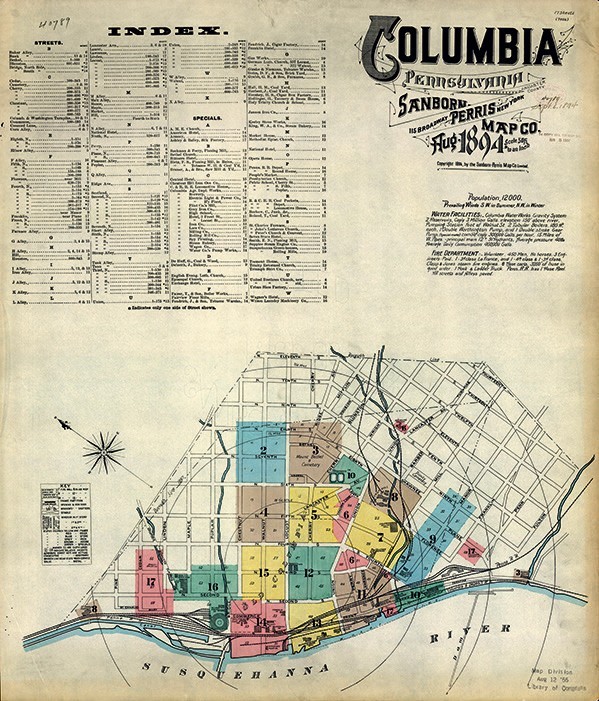

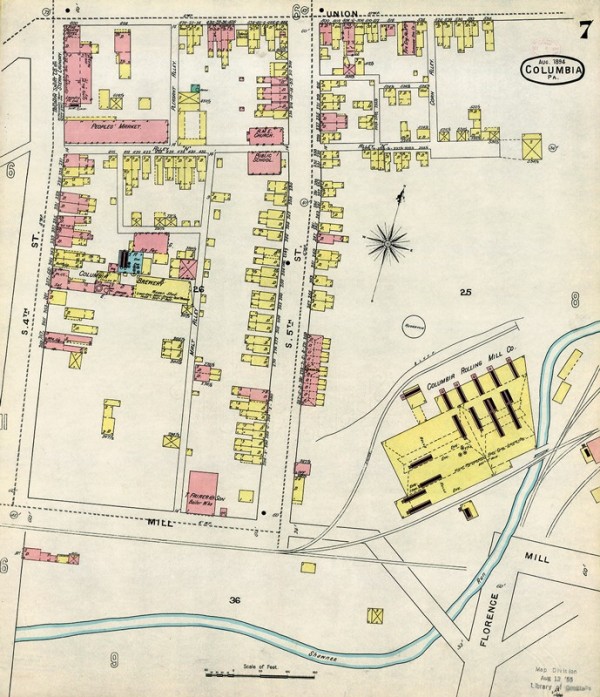

“Columbia, Pennsylvania,” Insurance Maps of Columbia, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (New York: Sanborn Map Company, November 1904), Sheet 1. 25 5/8 x 21 1/4".

Detail of Sheet 6 from the map in figure 66 showing the intersection of Union and Fifth Streets. The pottery of John Wesley, and later of the Isaac Ross and Wesley partnership, is on the southwest corner. The well established Mt. Zion Methodist Episcopal Church is also on the same block. This church was a focal point for the Underground Railroad in Central Pennsylvania.

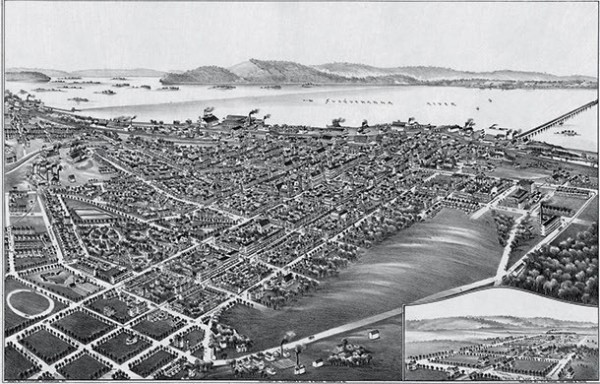

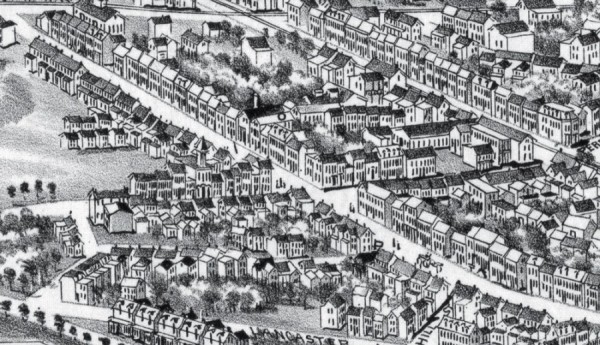

Thaddeus Mortimer Fowler and James B. Moyer, Columbia, Pennsylvania [map] (Morrisville, Pa.: T. M. and James B. Moyer, 1894). 17¾ x 27 1/8". https://www.loc.gov/ item/76695288/.

Detail of the view of Columbia, Pennsylvania, shown in figure 68. The location of John Wesley’s pottery is highlighted in red.

Face jug, John Dollings, White Cottage, Muskingum County, Ohio, ca. 1860–1870. Stoneware with Albany slip glaze. H. 12 1/4". (Courtesy, Ohio History Connection, H 53891; photo, Manko Photography.)

Annie B. Johnston, Stoneware Jug, ca. 1937, in Index of American Design. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Watercolor, colored pencil, graphite, and pen and ink on paper. 11 15/16 x 9 1/8". Information in the Index of American Design indicates the object was 12" in height. The drawing shows that the jug was doubled-handled, a trait not seen in other American face vessels. The overall anthropomorphic shape seems to foreshadow later Alabama folk pottery examples.

Photograph of “Stoneware ‘Voodoo’ head jug” in John Ramsay, American Potters and Pottery (New York: Tudor Publishing, 1947), fig. 75. Comparison of this photograph with the drawing illustrated in figure 71 shows that the artist took considerable liberties in her rendering.

Face vessel, attributed to Thomas Bennet Odam, Knoxville, Florida, or Pollard, Alabama, 1859–1867. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 11 1/2". (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Figural jug, John Fredrick Lehman, Randolph County, Alabama, ca. 1860. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 23 3/4". (Courtesy, High Museum, Purchase with funds from the Decorative Arts Acquisition Endowment, Accession #1994.19.)

Figural jug, John Fredrick Lehman, Randolph County, Alabama, ca. 1860. Ash glazed stoneware. H. 20 1/4". (Courtesy, Birmingham Museum of Art; photo, Sean Pathasema.)

Announcement in The Liberator (Boston, Massachusetts), April 3, 1863, p. 4.

Toby jug or pitcher, attributed to John Lehman, Randolph County, Alabama, ca. 1850–1870. Ash-glazed stoneware. H. 8 3/4". (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Detail of John Bull from “The Grand Deception,” Harper’s Weekly, February 22, 1862, p. 128. (Private collection.)

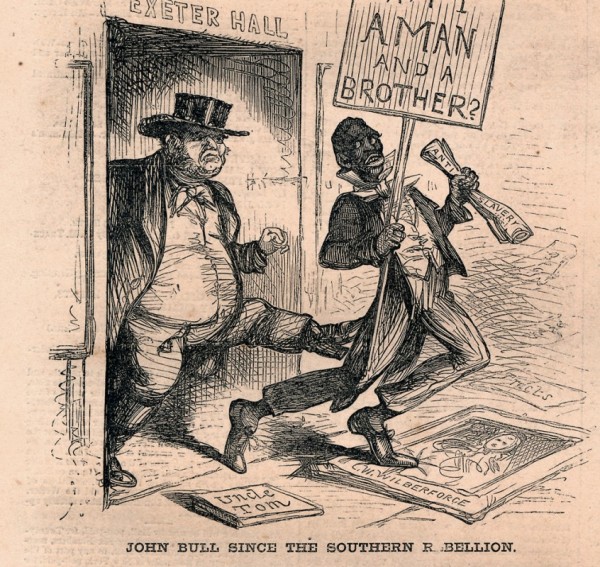

“John Bull since the Southern Rebellion,” Harper’s Weekly, September 28, 1861, p. 622. (Private collection.) The cartoon implies that England, needing the South’s cotton, kicks out an abolitionist from Exeter Hall, a site of anti-slavery meetings in London.

Face jug, Jesse Calvin Ham, Perry County, Alabama, ca. 1890–1900. Salt-glazed stoneware. H. 10". (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.) Marked “Drink My Blood | J.C. Ham”.

Detail of the “Drink My Blood” face vessel.

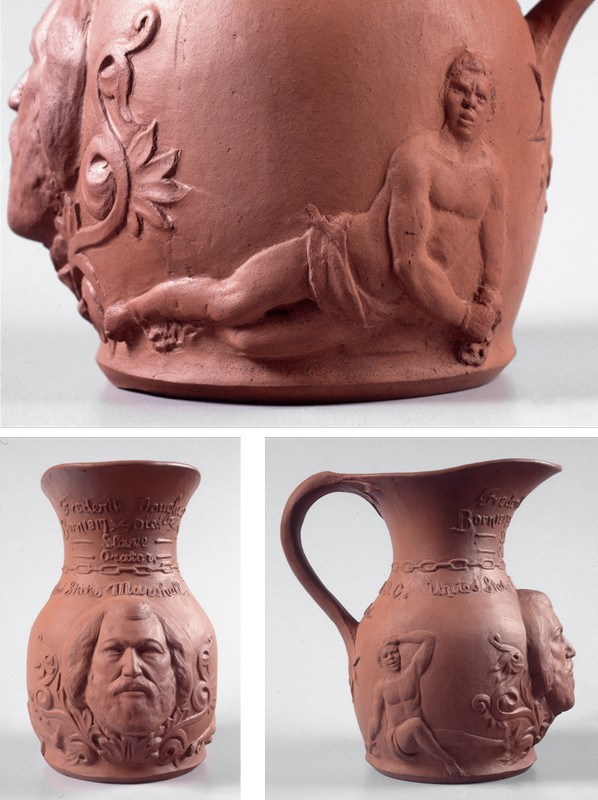

Frederick Douglass face pitcher, designed and copyrighted by J. E. Bruce, Albany, New York, 1896. Unglazed red earthenware. H. 10 1/4". (Courtesy, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, 1981.0353.01; photo, Gavin Ashworth.) The molded inscription reads “Frederick Douglass | Born 1817 | Died Feby 20 1895 | Slave Orator | United States Marshall, Recorder of Deeds D.C. | Diplomat.”

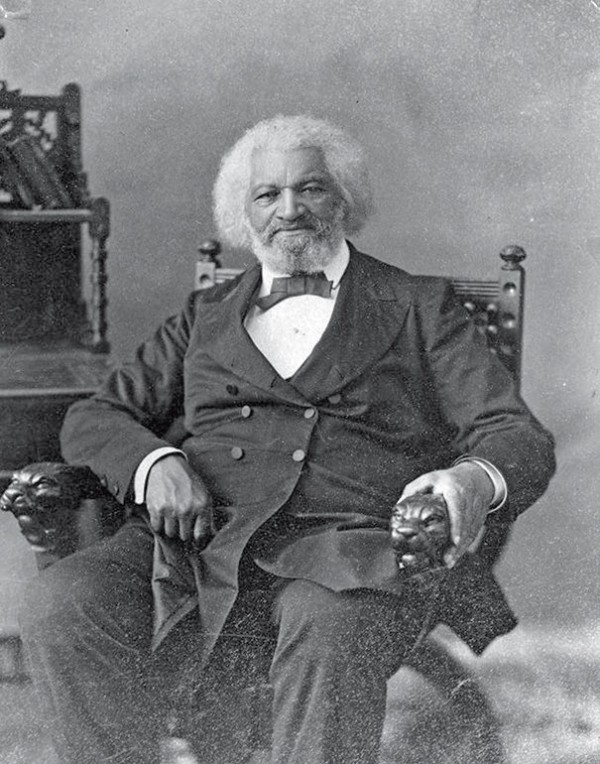

“Portrait of Frederick Douglass, abolitionist, journalist, and social reformer.” (Courtesy, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. New York Public Library Digital Collections.) https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/ items/6e4b45d3-4aae-6652-e040e00a1806645c.

Face pitcher, J. G. Baynham, Trenton, Edgefield District, South Carolina, ca. 1890. Stoneware with Albany slip glaze H. 7 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Face jug, Mark Baynham, Trenton, South Carolina, ca. 1890. Stoneware with Albany slip glaze. H. 5". (Courtesy, Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.) Impressed: “MARK”.

Face jug, attributed to John Leonard Atkins, Jug Factory Road, Greenville County, South Carolina, ca. 1900. Stoneware and porcelain with dark brown feldspar glaze. H. 5 1/2". (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Face vessel, William Decker, Keystone Pottery, Chucky Valley, Tennessee, 1892. Salt-glazed stoneware with paint. H. 8". (Courtesy, Bonhams, Skinner.) Incised on the bottom: “Made by Wm Decker | July 9th 1892” and “L.W. Berry.” This vessel appears to have had a wire bail handle.

Face jug, attributed to Wiley C. Meaders, Mossy Creek, White County, Georgia, ca. 1910–1930. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 10 1/4". (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Face jug, attributed to Otto Brown, Bethune, South Carolina, mid-20th century. Albany slip glazed stoneware. H. 8 1/2". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) The object bears china teeth.

Face jug, Lanier Meaders, Mossy Creek, White County, Georgia, 1974. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 8". (Author’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Face pitcher, Burlon Craig (1914–2002), Vale, North Carolina, ca. 1990. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 12 1/4". (Private collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Face jug, Billy Ray Hussey, Bennet, North Carolina, ca. 2000. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 12 3/4". (Courtesy, William C. and Susan S. Mariner Private Foundation; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Red Tails, Jim McDowell, Weaverville, North Carolina, 2022. Stoneware with Wertz Shino glaze. H. 16". (Courtesy, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, purchased with funds provided by Susan Brill Hershfield and Michael Hershfield.) https://www. artsvilleusa.com/jim-mcdowell-nashermuseum-part-three/.

Face jug, Stephen Ferrell, Edgefield, South Carolina, 2003. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 5 1/2". (Author’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) Inscribed: “FERRELL | MAKER | 2003.”

Face jug, Peter Lenzo, Columbia, South Carolina, 2004. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 8". (Author’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.)

Face jug, Michel Bayne, Lincolnton, North Carolina, 2004. Alkaline-glazed stoneware. H. 6 1/4”. (Author’s collection; photo, Robert Hunter.) Inscribed: “Bayne | Marker | Tigerville | SC.”

Introduction

For nearly two hundred years, among the more engaging yet equally mysterious genres of American ceramics has been the face vessel, produced by potters—both immigrant and native born, enslaved or free—from New England to Florida and westward to the Mississippi. Some critics in the field of decorative arts have dismissed these historical ceramics, and collectors themselves have used terms like “whimsical,” “grotesque,” or “ugly” to describe these animated but often contorted representations of the human countenance. Still others have advocated that such objects should be regarded as ceramic sculpture and celebrated for their aesthetic appeal. And while they can be appreciated as objets d’art, many of these vessels originally were intended for ceremonial or ritual use and to convey social, political, spiritual, or supernatural messages.

ALTHOUGH THERE HAS BEEN scholarly interest in the various American renditions since the early twentieth century, the history and meanings of face vessels remain largely enigmatic, and that definitive work has yet to be written. During the past several decades, face jugs have been the topic of exhibitions, symposiums, and general surveys.[1] These include venues at the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Greenville County (South Carolina) Art Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.[2] Publications include exhibition catalogs, online resources, articles, and essays. The broadest overview of American face vessels is found in George and Kay White Meyer’s Early American Face Jugs, illustrating over one hundred objects from a broad geographic perspective of all areas east of the Mississippi.[3] Their collection includes the largest known number of privately held Edgefield, South Carolina-made face jugs.

The semi-annual sales of the auction house Crocker Farm, Inc., in Sparks, Maryland, continue to offer newly discovered face jugs reclaimed from closets and attics across the United States.[4] Combined with their extensive research, excellent photography, and superb cataloging, the Zipp family at Crocker Farm has done more to inform the decorative arts field on American face vessels than any other scholarly forum.

This article summarizes some of the broad aspects of American face jugs, but more importantly, it introduces new findings of several previously unpublished examples. The essay is organized chronologically, from the earliest American face vessels to those made by contemporary potters.

Faces from Around the World

The human face has inspired potters since the inception of the craft. Anthropomorphic vessels, from abstractly stylized renderings to extremely realistic portraiture, are found in many cultures throughout time and space, reflecting the universal conviction of the animism of otherwise inanimate objects.[5] Elaborate drinking jugs and cups were often made in the form of the human head in the ancient Egyptian, Greek, Etruscan, and Roman cultures (figs. 1–3). In the Americas, the Indigenous ceramics workshops in Mesoamerica and Peru produced an incredible array of both human and animal face containers (fig. 4). The incorporation of the human face into their pottery is a hallmark of the Native American Mississippian culture (800 to 1600 CE) (fig. 5). Prehistoric potters in the British Isles and Europe also made anthropomorphic vessels, a practice that carried over into the medieval period (fig. 6).

On the cusp of the modern era, sixteenthand seventeenth-century German potters in the Rhineland produced stoneware wine and ale bottles embossed with the mask of a bearded man. Known as Bartmänner (German for “bearded men”), the hirsute faces applied to these pear-shaped bottles conveyed a sense of life worthy of a Disney animator (fig. 7). The quantities produced were staggering as European merchants shipped these hugely popular containers throughout the world. Nearly two hundred Bartmann specimens have been found in archaeological excavations at the outpost of circa 1607 Jamestown, Virginia (fig. 8).[6] Their near-human appearance contributed to the subsequent practice of using these bottles as magical devices for protection against witchcraft and conjuring. Such “witch bottles” have been found deliberately buried beneath houses in England, linking face vessels to spiritual or magical rituals.[7]

With the advent of the industrial revolution, British potters began to manufacture a variety of ceramics portraying classical satyrs, military heroes, and political figures in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (fig. 9). The iconic Toby jugs, modeled after a popular British folk character, were mass-produced in assorted sizes and colors (fig. 10). Salt-glazed stoneware jugs and mugs molded in the shape of human faces, relying on slip-casting technologies to make economical copies, became fashionable in England (fig. 11). These British-made examples are often cited as the inspiration for later American-made face vessels.

Early Face Vessels in America

Perhaps the prime candidate for the earliest documented American face vessel resides among the collections of the San Diego Museum of Art (fig. 12). It is impressed with the mark of stoneware potter Jonathan Fenton, who is best known for his Boston stoneware made between 1793 and 1797.[8] This particular face jug, however, is thought to have been made during his later pottery works in either Dorset, Vermont (between 1801 and 1810), or East Dorset (between 1810 and 1827) (fig. 13). The “J. Fenton” stamp that is found on this piece also occurs on other stoneware from the Dorset potteries (fig. 14).[9]

The face was fashioned by applying clay elements to a small, wheelformed jug made of a dark red clay covered in a black slip. The form of the jug and the sculpting of these facial features are rather crude and somewhat amateurish in contrast to Fenton’s works in Boston, which are distinguished by their beautiful finish. Given this, it may suggest that the jug was made by one of Fenton’s two sons in the early part of their training. Lura Woodside Watkins offers some anecdotal support for this in her Early New England Potters and Their Wares:

Once established in the pleasant village (East Dorset, Vermont), Fenton proceeded to train his sons in the potter’s craft. The elder, Richard Lucas, born in 1797, was soon able to help in the shop, Christopher Webber Fenton, nine years younger, grew up in the midst of the pots and shards and the burning of the kilns. Father and sons worked together until 1827.[10]

The jug reportedly descended in the Fenton family before it was donated to the San Diego Museum in 1947, further suggesting that it held special meaning and was retained as a keepsake within the Fenton families.[11]

In the fall of 2023, a newly discovered earthenware face vessel appeared among the offerings of Crocker Farm. Formed as a footed flask, the facial features were sculpted in the likeness of a Native American male (fig. 15). A specific maker was not suggested but it was generally attributed to the Northeast region of the United States and made sometime in the first half of the nineteenth century. The discovery led to yet another example, possibly by the same maker, among the collections at the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York. This remarkable jug, illustrated in figure 16, is covered in a thick dark glaze that suggests an African American ethnicity. Both of these face vessels share some characteristics with the marked Fenton example; however, their origins and circumstances of manufacture have yet to be identified and warrant much more research.

The earliest dated American face vessel is an elaborately molded and decorated pitcher discovered in 1924 by Frank McCarthy in Northampton, Massachusetts. With the date of 1833, the pitcher was first published in a 1925 Antiques research note titled “A Strange Face from Whately” along with photographs and a description (fig. 17).[12] The caption explicitly describes it as “Toby Pitcher,” referencing the previously discussed genre of British figural drinking jugs (fig. 18). The pitcher is attributed to the Whately pottery of Thomas Crafts, which was established in 1802 making utilitarian earthenware. Crafts and his sons expanded the operations, making black-glazed tableware in 1821 and, ultimately, salt-glazed stoneware in 1833, coinciding with the date recorded on the face pitcher.[13]

The Antiques article presents the following description of the impressed marks on the jug:

Across the forehead runs the legend “A. Friend. ‘to. My. Countrey.” On the left cheek appear “E. G. Crafts, Whately, Mass”. On the right cheek is “O’ The. Dimocratick. Press.”, and across the lower lip “United Wee Stand, Divided, Wee, Fall.” Beneath the handle is lettered in faded gilt the date 1833.[14]

The article goes on to interpret the marks and symbolism of the applied decorations:

As to the precise significance of the various inscriptions, no one is able to offer enlightenment. The members of the Crafts family are said to have been Massachusetts Democrats. They were, therefore, supporters of that irascible hero of the party, Andrew Jackson, who, in 1832, had for the second time been elected President of the United States. The fact may account for the display of patriotic enthusiasm. But it in no wise explains the curious mixture of symbols which appear in relief on the jug: six stars, three on each side; and two sprays of rose, thistle and shamrock, well modeled and charmingly disposed, flanking the handle.

The jug was published again shortly thereafter in John Spargo’s 1926 Early American Pottery and China with photographs of the side and back (fig. 19).[15] He used the term “grotesque” to describe the rendered facial expression, suggesting that it was not intended as a portrait. Spargo cautioned that since the date was applied in gilt, not impressed, it may have been added after the actual date of its creation. There is no other reason however, not to accept 1833 as the jug’s date of creation.

The jug appears yet again in Lura Woodside Watkins’ Early New England Potters and Their Wares, where she suggests a drastically different interpretation. She writes that the “grotesque” jug may have been made as a caricature of Elbridge Gerry Crafts and shockingly ignores the patriotic or political connections of the applied motifs and inscriptions:

There is no evidence that Elbridge Gerry ever made pottery: he was a farmer. Because his name appears on a grotesque pitcher made in 1833 (he was then nineteen), it has been assumed that he modeled the piece. More probably the jug represents a portrait of the boy made in jest by one of his older brothers. A glance at the family pictures in the History of Whately shows the reason for this opinion. The date 1833 stands for the year when the stoneware pottery was started—a circumstance that explains the sentiments: “United We Stand: Divided We Fall”; for at that time all three sons were at home with their father.[16]

In reanalyzing the jug and reconsidering the symbols—and most importantly its historical context—I have suggested the following interpretation:

Another Crafts family face vessel came to auction recently and is thought to have been made around 1838 (fig. 21). Attributed to potter Martin Crafts of Nashua, New Hampshire, the stoneware pitcher carries the impressed mark “T. Crafts & Co. | Nashua”.

The Nashua pottery was an expansion of Martin’s father’s Whatley operation and initially managed by another son, James M. Crafts. By 1839 Martin was in Nashua, where he oversaw the pottery for at least ten years.

The pitcher was thrown and then hand-modeled to create the facial features. The name “Sloop Orange” is impressed on the pitcher, suggesting it was a presentation piece for a sailing vessel. In their catalog entry for this pitcher, Crocker Farm references a late eighteenth-century ship of the same name owned by Moses Crafts, Martin’s grandfather, that was routinely sailing between New York City and Newburgh, New York.[21] Presumably the sloop Orange was still in operation around 1839 when the pitcher was made.

In overall shape and appearance, the pitcher is not too dissimilar from the 1833 Whatley example, but aspects of the facial modelling are distinctly different. Previous observations have noted the raised cheekbones, Roman nose, and almond-shaped eyes of the molded face, yet no comment had been proffered as to the ethnicity of the subject. The village of Nashua was originally called Indian Head after a carving left on a tree following a 1724 skirmish between the settlers and Native Americans. The name Nashua itself is a Native American word meaning “land between two rivers.”[22] Many businesses adopted the Indian Head symbol for their logos and branding of products (figs. 22, 23). Further indication that the jug represents a Native American portrait includes the pierced ears and the use of dark brown Albany slip to mimic the traditional face paint used by various American tribes (figs. 24, 25).

A smaller face pitcher from the Nashua pottery resides in a New England private collection and is illustrated in Henry C. Baldwin’s The Stoneware Potters of Ashfield, Massachusetts (fig. 26).[23] The pitcher is unsigned but clearly related to the previously discussed example, having a similar form and brown slip glaze. Impressed on the forehead in printers type is “MY COUNTRY” and on the top lip “ITS LAWS”. On the left side of the jug is the impressed name “CHARLES KEMP”, who is listed as a “trader” in the 1843 Nashua city directory.[24] On the right side, the pitcher is impressed “NASHUA”.

The overall modeling of the pitcher’s facial features is far less sophisticated than the previously discussed Sloop Orange example and is almost cartoonish, with an exaggerated nose and large, protruding ears. On this example, nothing suggests a Native American association. It is difficult to think that both were made by the same person within the Crafts shop. Nothing more is known about Charles Kemp other than his occupation as a trader, although he conceivably did business with the Crafts family. The words on the front of the pitcher having some general patriotic connotation may further relate specifically to Charles Kemp’s political or business standing.

A significant face pitcher, made around 1840 in nearby Medford, Massachusetts, captures the powerful visage of General Toussaint Louverture (1743–1803), the former slave who led the enslaved population to freedom during the Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) (fig. 27). The identification of that pitcher was discussed at length in the 2002 volume of Ceramics in America, “ ‘The Very Man for the Hour’”: The Toussaint L’Ouverture Portrait Pitcher.” [25] The pitcher was likely commissioned by one of the New England abolitionist societies for whom the image of Louverture served as a rallying device for the antislavery cause throughout most of the nineteenth century (fig. 28). The pitcher is slip cast from an original model that has either not survived or not been found; at least three examples are known.[26]

The cause of abolition was manifested in another American face pitcher, this one made by Philadelphia potter Ralph Bagnall Beech (1810–1857) around 1848 (fig. 29).[27] The Rockingham-glazed pitcher is a portrait of Irish politician and activist Daniel O’Connell (1775–1847). O’Connell pushed for the emancipation of Catholics in Ireland to ultimately sit in the British Parliament (fig. 30). He was a vocal opponent to slavery in the United States. In 1845 famed American ex-slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass (1818–1895) found inspiration from hearing an O’Connell speech during Douglass’s tour of Ireland following the publication of his Narrative of the Life of Fredrick Douglass, Life of an American Slave.

The pitcher has a history of ownerships by early American ceramic scholar Edwin Atlee Barber (1851–1916) and subsequently Francis P. Garvan (1875–1937), who purchased it at Barber’s estate auction and gave it to the Yale University Art Gallery in 1931 (fig. 31).[28] The style of the pitcher is very reminiscent of British-made examples from the early nineteenth century, reflecting Beech’s British heritage and his early training at the Wedgwood factory in Burslem. He moved to Philadelphia in 1842 and worked for Abraham Miller before opening his own pottery in the city.[29] After Beech closed his pottery in 1857, the molds were acquired by Philadelphia potter Thomas Haig (1812–ca. 1893), who continued to produce copies of the jug as late as 1891 (fig. 32).[30]

Early Mid-Atlantic Face Vessels

The origins of the hand-modeled face vessel as a production item for American utilitarian potters remain a mystery and a somewhat contentious issue among ceramics scholars. We can, however, identify with some certainty the cobalt-decorated, salt-glazed stoneware face vessels made by white, urban-based manufacturers in several Mid-Atlantic potting centers during the nineteenth century. The best-known examples of this type are the pitchers and jugs produced by Henry Remmey Jr. (active 1827–1878) and his son Richard C. Remmey (1859–1892) in Philadelphia from the 1830s to around 1850.[31] Similar in format to English-made face examples (see fig. 11), these jugs were individually modeled rather than mass-produced from molds.

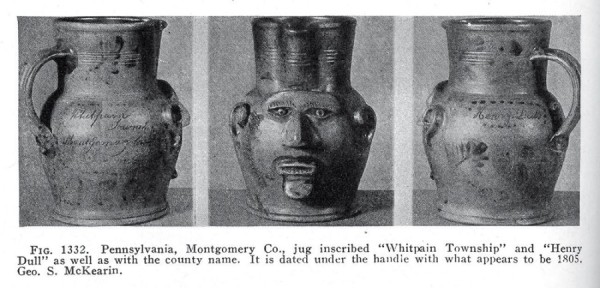

An example of a Remmey style face pitcher from the George S. McKearin collection was published by Warren Cox in 1944 (fig. 33).[32] The vessel is inscribed “Henry Dull” and “Montgomery County” and with what appears to be the date 1805. Rather than a date of manufacture, however, the date must refer to the birth of Henry Dull (1803).[33] According to the 1837 Philadelphia city directory, a George Dull is recorded as a tavern owner on North 2nd Street, the same street as the Remmey pottery.[34] Other Dull family members are also listed in close proximity to Henry Remmey Jr. in Philadelphia.

Several other Remmey face vessels are known to exist. One of the more noteworthy examples is a documentary pitcher dated 1838, acquired in 1952 by the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution (fig. 34).[35] In addition to the modelled and applied facial features, the pitcher proclaims in impressed printers type “KEEP ME FULL”, reflecting its intended use to be filled with alcohol for the age-old rituals of commemoration and celebration, fulfilling the identical function of the ancient Greek and Roman drinking vessels that we venerate in museum displays throughout the Western world. The vessel was made for or presented to a Lewis Eyre, who appears as a carpenter in the nineteenth-century Philadelphia city directories.[36]

The Remmey-made vessel illustrated in figure 35 is among a small group that has faces on both sides of a harvest jug form. Recent discoveries by the Crocker Farm auction house have identified similar stoneware face pitchers attributed to Samuel Bell, of Winchester or Strasburg, Virginia, circa 1835–1845, and Elisha B. Hyssong, of Huntingdon County, Cassville, Pennsylvania.[37]

A small group of distinctive, black-glazed earthenware face jugs has been tentatively attributed to the manufactory of the Thorn pottery in Crosswicks, New Jersey.[38] These jugs incorporate kaolin slip to create the white of the eyes, while the teeth are created from a solid pad of kaolin and subsequently incised. A dated example sold recently at Crocker Farm with the incised date “Oct. 5. 1844” (fig. 36).[39] Additional research is needed to fully understand this group of earthenware face vessels, but the dated example again helps to confirm that American potters in the Mid-Atlantic region were fully engaged in face jug production by the 1840s.

“Made in Africa”: Edgefield Face Vessels

Without question, the most intriguing of all American face vessels are the alkaline-glazed stoneware examples made by the enslaved potters in South Carolina’s Edgefield District in the mid-nineteenth century (fig. 37). Intensive research has been devoted to this genre of ceramics over the last twenty years, augmented by exhibitions and publications. Yet much of the recorded information remains speculative and murky despite the large number of recorded vessels. Nearly two hundred examples have been documented to date, the vast majority being small jugs, although larger harvest jugs, pitchers, and cups were also made.[40] The actual makers remain anonymous, but it is widely accepted that most, if not all, were enslaved potters at numerous factories in the greater Edgefield area. The earliest date of production has been suggested to be the mid-1840s, with production subsiding after the outbreak of the Civil War.[41]

Material culture scholars have asserted that Edgefield face vessels were not just functional jugs and cups, but also served as powerful ritual objects used in the practice of conjuring—or at the very least, they had some inherent connections to African American spiritual life.[42] Of particular significance to this argument is the use of kaolin for the eyes and teeth, since the fine white clay is celebrated in many African cultures for its magical qualities and its use in the decoration of ritual objects. Early American ceramics collectors so closely identified Edgefield face vessels with African art that they were often mistaken in doing so. Pioneering American ceramics historian Edwin Atlee Barber, who had connected their making and use with Edgefield’s slave population, emphasized these African roots of the vessels.[43] In one publication, he specifically notes that “I have seen [face jugs] in antiquarian collections labelled ‘Native Pottery made in Africa.’”[44]

Barber ultimately conceded that the “belief that they are of African origin is erroneous,” but the association remained an important observation later championed by art historian Robert Farris Thompson in his 1969 article, “African Influence on the Art of the United States.”[45] Thompson’s continued work in the 1980s emphasized the connection between traditional African art and the anonymous makers of the Edgefield face vessels.[46] As with African sculpture, the aesthetic of the Edgefield face vessel cannot be separated from its intended spiritual function. The starkly modeled faces transform a decorative object into a portal for some form of communication. And like African sculpture, most of the Edgefield face vessels associated with enslaved potters rely on visual abstraction rather than realistic depiction.

One such graphically expressive Edgefield face cup appeared recently at public auction (fig. 38).[47] Confirming Barber’s reporting, the cup bears a nineteenth-century collector’s label clearly proclaiming that the cup was “Made In Africa,” with further notation that the object was: “Presented to T H B | by | Horace J. Smith | of Phila | Pa.” (fig. 39). While “T H B” has yet to be identified, Horace J. Smith (1832–1906) was a well-known Philadelphia Quaker and a multi-faceted businessman and philanthropist (fig. 40).[48]

The cup has been stylistically associated with enslaved potters at Colonel Thomas Davies’ circa 1861–1864 Palmetto Firebrick Works near Bath, South Carolina. How Smith may have originally acquired the face cup is a fascinating question that has yet to be answered. He was predisposed to an interest in ceramics as he was involved in the china and porcelain trade with the firm Wright, Smith, and Pearsall in Philadelphia in the 1850s. The Civil War interrupted his business while he worked for the United States Sanitary Commission nursing both Union and Confederate soldiers in field hospitals. Intriguingly, in 1863 the Thomas Davies Factory produced “earthen jars, pitchers, cups and saucers” in large quantities for use in Confederate hospitals.[49] Whether this has any connection with Smith remains to be investigated.

In advance of the 1876 Centennial Exposition, Smith worked on the Advisory Committee of the Bureau of Agriculture. Around 1883 he embarked on a trip to Europe, where he took up permanent residence in Birmingham, England, until his death in 1906. He was buried in West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, a site he helped his father establish and of which he was comptroller in the 1870s.

An interesting connection exists between Smith and Martha Schofield (1839–1916), a Quaker abolitionist and suffragist who founded a school in Aiken, South Carolina, for freed African Americans (fig. 41). The school opened in 1868 and was partially funded by the Pennsylvania Friends Relief Association. She may have met or known of Horace Smith during her service in the Civil War when she volunteered at an army hospital on Darby Road in West Philadelphia.[50]

We don’t know the full relationship between Smith and Schofield, but in 1886 he writes to her and sends her a facsimile copy of what he refers to as “The First Formal Protest against Slavery” for Schofield’s school (fig. 42).[51] The original 1688 document, known formally as The Germantown Protest, was the first formal petition against slavery in America, presented to the Quaker Germantown Meeting in Pennsylvania.[52] In spite of its importance, the document was “lost” until 1844, when it was rediscovered by Nathan Kite and reprinted in The Friend: A Religious and Literary Journal.[53] Smith must have personally known Kite since he specifically mentions him in the letter to Schofield.[54]

Whether or not Smith’s relationship with Schofield may have been a possible source for his face cup remains unknown. There is no question that the link between Philadelphia and Edgefield remains a fertile ground for exploring the early collecting history of face vessels. It is interesting to note that Philadelphia photographer James A. Palmer (1825–1896), who made extensive photographic records of the Aiken vicinity, also recorded the Schofield school in several views (fig. 43). Palmer is somewhat famously known for capturing the first photographic records of Edgefield face vessels in two 1882 stereopticon photographs titled An Aesthetic Darkey (fig. 44) and The Wilde Woman of Aiken. The satirical images feature a young man and young woman who may very well have been students at Ms. Schofield’s school. Further research may provide additional connections between the history of Edgefield face vessels and their early appearance in Philadelphia contexts.

What Is a “Monkey Jug”?

When Edwin Atlee Barber first introduced Edgefield face vessels in print, he chose the Clay-Worker magazine for his article titled “Some Curious Old Water Coolers Made in America.”[55] The choice of publication was surprising: the magazine was billed as “The Official Organ of the National Brick Manufacturers’ Association of the United States of America,” though it also proclaimed it was “a journal devoted to all clay working interests.” In his article, Barber illustrates for the very first time in a professional publication an Edgefield face vessel, captioned “Monkey Jug of the Southern Negro” (figs. 45, 46).

The article goes on to describe a “monkey” jug as having “a straight spout, a neck for receiving the waters, and a handle for carrying.” Somewhat strangely, the Edgefield face jug that is illustrated does not meet these criteria, having the traditional jug form with a single handle and spout. Another illustration in the short article does show an “earthen water monkey” correctly (fig. 47). But as late as 1917, the term monkey jug was still being used inconsistently by Barber (figs. 48, 49).

Today the terms “harvest” or “stirrup” jug seem to be used interchangeably by collectors to describe a specific type of drinking jug with a strap handle and opposing spouts. There has been quite a bit of speculation over the introduction of this form to the New World, as it has had antecedents in Southern Europe for centuries.[56] The form is firmly rooted in the repertoire of the Spanish terracotta potter, where it is called the botijo and is still produced today (fig. 50).[57] Southern ceramics historian John Burrison suggests the origin of the term “monkey” is related to an Afro-Caribbean term for thirst.[58]

The transmission of this harvest or stirrup jug style to the American potteries remains one of ceramic history’s minor mysteries. Artist Seth Eastman (1808–1875), a U.S. Army infantry officer who was stationed in Florida in the 1830s during the Second Seminole War (1835–1842) includes a “monkey” in an oil painting of a Seminole prisoner (fig. 51). The inclusion of this vessel was presumably preceded by the preliminary pencil sketch by Eastman dated “Feb. 1840” shown in figure 52. The drawing shows a two-spouted jug, most likely of Spanish origin, being suspended by a rope with the explicit notation “a monkey for cooling water.”[59] This version may have been the inspiration for Southern potters beginning perhaps as early as this date. Barber suggests that it may have indeed been an army officer who introduced the form to Pennsylvania potters somewhere around the middle of the nineteenth century:

It is interesting to learn that the same type of vessel was produced at a small pottery in Westchester, Pa. upwards of a half century ago . . . . The oldest inhabitants believe that its manufacture in this section may be explained on the supposition that more than fifty years ago a jug of this form was brought East by an army officer who resided in Pennsylvania.[60]

Southern potters appear to have been producing monkeys by that time (fig. 53), and as noted before, the form had found its way to the Mid-Atlantic and New England in the 1840s (see fig. 35). Edgefield potters may also have been using the form for their face vessel creations perhaps as early as the 1840s, (fig. 54). The monkey jug moved westward into Ohio later, in the 1860s.

Thomas Chandler and Edgefield Face Vessels

One of the more recognizable of all Edgefield-made face vessels was created as an alkaline-glazed monkey or harvest jug (fig. 55). It is stamped “CHANDLER | MAKER”, the mark of Thomas Chandler (1810–1854), a white potter who was an accomplished and prolific manufacturer in South Carolina’s Edgefield District from 1838 to 1852. Thomas Chandler was born in Virginia and as a young man was trained in the Baltimore stoneware tradition of cobalt-decorated salt-glazed stoneware. Chandler relocated to the Edgefield District in the 1830s, where he adopted the Southern tradition of alkaline-glazed stoneware. There he worked in several shops that included enslaved potters producing a wide range of utilitarian forms: pitchers, jugs, and jars. Chandler developed sophisticated glazing techniques and introduced the decorative technique of slip trailing.

Chandler’s face vessels are a conundrum and thus a subject of continued discussion among ceramics scholars. Did he introduce the form to the Edgefield potteries, where it was subsequently adopted by the enslaved potters, or was the face jug form a parallel innovation from within the various communities of enslaved African potters? In his 2013 article “From Baltimore to Edgefield: The Influence of Thomas Chandler on 19th-Century Stoneware,” Southern pottery collector and author Phil Wingard has suggested that Chandler brought the idea of the face vessel to Edgefield after being exposed to early Mid-Atlantic examples, perhaps made by the Remmey family of potters in Baltimore.[61] There are six or seven surviving examples from South Carolina, unsigned but attributed to Thomas Chandler or potters working in association with him (figs. 56, 57), that are considered to have been made during the 1840s and early 1850s. All of these have highly sculpted facial features and suggest either portraiture or caricature, in contrast to the more abstract “African style” face jugs. Some ceramics historians have argued that the African style face vessels can be traced to the arrival in 1858 of the slave ship Wanderer bringing native Africans to the workforce of the Edgefield potteries.

Certainly, a great deal more study of the more highly sculpted Edgefield face is necessary. The theory that these may suggest portraiture is reinforced by a small group that have incised names on them. The most powerful and emotive face vessel of this group is shown in figure 58. The facial features sculpted on this stirrup jug have a much more lifelike appearance than the vast majority of Edgefield examples. The maker of the jug achieved a level of portraiture far above all other known examples. Does the jug represent a specific person? A tantalizing clue is the name “Dick Abney” inscribed in script on the jug. A Dick Abney is found in the 1866 U.S., Freedmen’s Bureau Records for Aiken (South Carolina) when he enters a sharecropping arrangement with his presumably former enslaver, James C. Abney.[62]

A South Carolina Face Vessel Maker in Pennsylvania

The story of Thomas Chandler and his involvement with Edgefield face vessels has taken a dramatic turn recently during the reevaluation of a lead-glazed earthenware face vessel owned by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (fig. 59). The face vessel, in the form of a harvest jug, had first surfaced in a Sotheby Parke Bernet Inc. auction in New York in 1982, where it was described as “Glazed Redware Grotesque Jug, First-Half 19th Century.”[63] No information was given as to where it was made nor its maker. It was subsequently offered to Colonial Williamsburg in 1984 for purchase. During the acquisition process, ceramics dealer and historian Gary Stradling provided information to Colonial Williamsburg’s curators, that a similar face vessel had been recorded around 1940 and had been found in “Southern Lancaster Country near Washington Borough.”[64] Stradling only had a poor-quality Polaroid image of the jug, but he had noted that incised deeply across the back was “Willa | Frisby | Made by | John Westly” and on the bottom “1870”. That jug surfaced in 1993 at the sale of the collection of Robert R. and Joanne Dreibelbis by Pennypacker’s Auctioneering and Appraisal Services on May 17, 1993 (fig. 60).[65]

Despite the number of clues suggesting that the face jug was indeed of Pennsylvania manufacture, Phil Wingard had proposed that the face vessel may have been of Baltimore origin and served as antecedent to the Chandler-associated Edgefield examples. As previously discussed, the Edgefield group of Chandler face vessels revolved around a single marked example, as well as several others that shared similar sculptural features. Wingard wrote:

I believe Chandler learned how to make face vessels while he was in Baltimore. At least three earthenware face vessels exist that I attribute to this Chandler school, and I believe they were made in Baltimore during the 1820s. These vessels are in the shape of what I call the Southern harvest-jug form, with a pouring or drinking spout and a nipple spout for sipping or venting, and with a bell handle placed across the top of the vessel. This form matches the known Chandler-signed Edgefield example, and was also used on several other Edgefield face jugs in this group, which strengthens the connection. The redware examples share the following characteristics with the signed stoneware Chandler face vessel: kaolin inset eyes with colored pupils, kaolin inset shaped teeth, large and distinctive lips and noses, and sunken eyes, to varying degrees, with Toby sculpted cheeks. The three earthenware examples and the stoneware example are near-exact copies, sharing a highly developed expressive face and the distinctive harvest-jug form.[66]

While Wingard was correct in recognizing the typological similarities of the harvest jug form and the manufacturing characteristics, he provided no evidence that Chandler ever worked in earthenware in Baltimore—nor anywhere else for that matter. In addition, although little formal study has been undertaken on Baltimore earthenware makers of the nineteenth century, the fabric and glazing of the face vessel bore no relationship with archaeologically recovered redwares from the period.[67]

In preparation for this article, I revisited all the information pertaining to the Colonial Williamsburg face vessel to understand Wingard’s attribution to Baltimore better. During the process, I went in search of potter “John Westley,” retracing Gary Stradling’s 1983 search of Philadelphia city directories. Although I found a John Westley listed in 1850, there was nothing to suggest he was potter or had anything to do with the craft. But what I did find, in searching Brandt Zipp’s “African-American Potters: 1850–1880 Federal Census Extract” (a running catalog of identified American Black potters) was a John Wesley working in Columbia, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in 1880.[68] Most important was the information that leaped off of the screen, that Wesley was born in South Carolina in 1835. I immediately contacted Brandt to further discuss the ramifications of this discovery, and he excitedly began to explore further avenues of research, some of which are included in this discussion.[69]

How and where the inscribed “1870” face vessel was made remains in question. Was Wesley already working in Columbia by that time, or was he perhaps working in one of the many potteries in Lancaster? Pennsylvania was the most densely populated pottery manufacturing state in America; in 1810 there were 164 operating potteries, many centered in the greater Philadelphia region.[70] In the nearby town of Lancaster, there were seven pottery establishments in 1860, including the larger potteries of Henry Gast, Henry Ganse, and Daniel Swope.[71]

Evidence for pottery making in Columbia is sparse despite the many potteries in nearby Lancaster. The town, situated along the Susquehanna River and with wharves, canals, and railroads, facilitated the transportation of raw materials, pig iron, agricultural products, and people. In the second half of the nineteenth century, a dozen iron furnaces operated within the city limits. An 1874 city directory for Columbia lists John Wesley as a colored laborer in Furnace Alley (fig. 61).[72] But by 1878 the city directory for Columbia lists him as a colored potter with a shop in Corn Alley (fig. 62).[73]

In 1878 an entry in a Lancaster newspaper, the Intelligencer Journal, announces that an “old time South Carolina barbecue will be held on May 30th in Heise’s woods” in Columbia (fig. 63).[74] Heise woods appears to have been a large tract of undeveloped land on or near the Susquehanna River, long-standing property of one of the founding families of Columbia.[75] In attendance were John Wesley, specifically cited as a potter, along with Matthew Gibson, Edward Tailor, Wesley Hill, Zach. Snively, James Jones, and Mary Henderson. Initial exploration into the biographies of these individuals reveals that they all were Blacks and employed as laborers—or as a washing woman in the case of Mary Henderson. Gibson was born in Tennessee, Tailor in Virginia, and Jones in Maryland; both Snively and Henderson appear to be Pennsylvania natives. Clearly Wesley was the “pitmaster” in bringing South Carolina barbeque to Columbia, and perhaps the other individuals worked alongside Wesley.

John Wesley appears in the 1880 Federal Census (fig. 64) and in an 1884 city directory as a “potter.”[76] He continues to be listed in Columbia’s 1892 and the 1894 directories, but of special note is an 1892 newspaper announcement that: “John Wesley and Isaac Ross are erecting a new pottery on Fifth street, near Union. The concern will be quite a large one, the oven having a capacity of 1,400 pieces (fig. 65).”[77] Not much additional information about Ross has been forthcoming other than his being listed as a Black laborer living at 221 Fifth Street, the general location described in the above newspaper announcement (figs. 66–69).[78] The 1894 Lancaster city directory indicates that John Wesley and Issac (Isack) Bradley were working jointly in both Lancaster and Columbia. Bradley was also an African American and was born in Delaware in 1855. His wife, Catherine, is listed as being born in South Carolina, suggesting another possible South Carolina connection with Wesley.

The question of course is: Was Wesley trained in Edgefield before coming to Columbia, and if so, when and how did he bring the craft to that town? No information has been found to help in answering these questions, keeping the possibilities in the realm of speculation. We do know that Columbia was a major point of entry for those fleeing Southern slavery. In fact, Columbia has been called the birthplace of the Underground Railroad.[79]

Wesley’s companions at the South Carolina barbeque may all have been former slaves from Virginia, Maryland, and Tennessee. His Columbia pottery location at the intersection of 5th Street and Union is in the same block as the Mt. Zion A.M.E. Church. That congregation arose beginning in 1817 from the arrival of escaped or emancipated slaves from Southern states. In 1872 a large brick church was built on the present site and remains a focal point for the considerable Black community of Columbia.[80]

While much more work remains to be done on the pottery of John Wesley and his partners, it is safe to say that the three face vessels attributed to him were the result of his exposure to examples made in South Carolina’s Edgefield potteries. He would have been a young man during the 1850–1860 production period of the Chandler type of face vessels. If this is the case, Wingard was correct in making a stylistic connection between the group of harvest jugs as being related to the Edgefield/Chandler school. However, instead of being the antecedent to the Edgefield production, the Wesley examples produced later in Columbia are a continuation of the style.

Later Edgefield and Points Beyond

The influence of the Edgefield face vessel tradition follows the later westward expansion into other parts of the South and the Ohio Valley following the Civil War, where white potters began making face jugs as production items. Perhaps the most distinctive are those made by Ohio potter John Dollings (1835–1926).[81] In the 1860s at the C. W. Stine Pottery in White Cottage, Ohio, Dolling produced a series of dramatically modeled and black-glazed face vessels of an African American male (fig. 70). Dollings’ realistic jugs are noted for the added details used to create the textures of hair, eyebrows, mustaches, and even sideburns, using clay shavings applied in the wet state of modeling.

A tantalizing reference to a remarkable face vessel attributed to the Knox Hill pottery in Walton County, Florida, is recorded by a drawing produced for the Index of American Design program by Annie B. Johnston in 1937 (fig. 71). The drawing is among seventy-four in the online Index of American Design of objects that were in the Florida State Museum, now the Museum of Florida History.[82] A photograph of the vessel, described as a “Voodoo Jug,” was published in John Ramsay’s 1947 American Potters and Pottery (fig. 72).[83] When compared to the drawing, it becomes clear that Johnston took considerable liberties to enhance the aesthetic qualities of the facial features and the overall form of the jug, as the photograph suggests a much more crudely fashioned vessel.

The jug was on loan to the museum from the 1930s to the mid-1950s; its present ownership is unknown.[84] The jug is attributed to Knox Hill pottery, a short-lived pottery operated by Robert Turnle and Thomas Bennet Odom (1834–after 1892).[85] Very little is known about Turnle, but Odom was a potter who worked in Pollard, Alabama, before coming to Knox Hill, Florida, in around 1859.[86] His time in Florida may have been disrupted by the onset of the Civil War, and by 1864 he was back in Pollard. He reputedly left his family to settle in Texas around 1867, and he is recorded as working at the T. B. Odom Pottery by 1870 in Upshur County.[87]

The Knox Hill pottery face jug was the only evidence of Odom’s face vessels until recently, when a small face vessel appeared at auction (fig. 73).[88] The jug has similar facial characteristic as the Florida example, although it may be possible that it was made during Odom’s time in Pollard, Alabama.

Several face and figural vessel makers are known in the pottery traditions of Alabama. Perhaps the earliest is John Lehman (ca. 1825–1883), a German immigrant who began potting in the Rock Mills area of Alabama in the 1850s. Lehman worked in the local alkaline-glazed stoneware tradition, producing utilitarian wares but more notably a series of ceramics with political content, such as jars with applied molded images of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. In addition, and perhaps most important, is a group of three life-like portrait jugs featuring a distinctively attired Black male (figs. 74, 75). All the jugs have slight variations in size and details but clearly represent the same individual. Various writers have sought to identify or characterize the Black male but without success.

Ceramics historian John Burrison has interpreted the figure as possibly being an African American state or federal legislator elected during Reconstruction. He goes further to say that hoop earrings were the trappings of a pirate. However, a visual analysis of the figure’s clothing—the stand and fall collar along with the ruffled shirt worn with a cravat—indicate a 1790–1800 date.[89] With hoop earrings and what may be a Phrygian or liberty cap, I suggest the figure depicts the previously introduced Toussaint Louverture. As noted earlier, Louverture was for African Americans the symbol of a successful struggle for freedom and liberation from the bonds of slavery. The style of the figure’s clothing fits perfectly with the 1791–1804 dates of the Haitian revolt.

Why would Lehman choose Louverture as his model? On the cusp of the American Civil War, Louverture’s image and life story were powerful influences for Northern abolitionists and Southern sympathizers. His biography was published in America in 1863 and widely circulated.[90] Abolitionist Wendell Phillips’s published lectures were featured in many American newspapers (fig. 76). The notoriety of Toussaint Louverture’s story and African American agitation helped push Abraham Lincoln to take “the most decisive stand ever taken by an American president against slavery” and allow the enlistment of Black men in the Union Army.[91] The ceramic homage to Louverture would have been framed by Lehman’s political leanings as an immigrant craftsman amidst the Southern turmoil during the American Civil War. Alabama folklife scholar Joey Brackner has written that:

Randolph County, Alabama, in 1860 was a community divided over the prospect of secession. The area had relatively few slaves, and some citizens, such as local lawyer and potter Cicero Hudson, considered themselves Union men. However, once hostilities began, the Hudsons and others sent their sons, brothers, and fathers to fight for the Confederacy. Whatever John Lehman may have thought about secession, he too donned Confederate gray.[92]

A recently discovered hand-modeled and ash-glazed Lehman figural jug may also carry a political message concerning Anglo-American relations during the American Civil War (fig. 77). Modelled as a well-dressed, rotund gentleman, the jug is similar to the generic mid-nineteenthcentury Toby jugs made by British and American earthenware potters working with the dark-brown Rockingham glaze. The clothing details suggest a circa 1860 date of manufacture, and the figure represents “John Bull,” the personification of the British government, used widely in political cartoons and similar graphic works (fig. 78). John Bull was widely lampooned during the Civil War for England’s hypocritical financial support of the Southern cause while denouncing the institution of slavery (fig. 79); Lehman’s suspected sympathies of the abolitionist cause likely influenced his decision to create a ceramic version.[93]

Lehman’s figural ceramics may have been the catalyst for the proliferation of figural vessels made by other Alabama potters in the latter years of the nineteenth century. None of those later examples comes close to rivaling Lehman’s sculptural realism; most exhibit a somewhat primitive appearance. One particularly graphic, albeit disturbing, figural jug was made by potter Jesse Calvin Ham (1870–1933) of Perry County, Alabama (fig. 80). With a prominent gaping mouth lined with jagged, broken porcelain plate fragments, the jug is inscribed “Drink My Blood”. Although popularized by Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published in 1892, vampire lore has existed in America since the eighteenth century. Does the inscription “Drink My Blood” refer to the vampiric practice, or to the alcohol contents of the jug? Certainly, the frightening and lethal-looking dentition suggests a connection with the former (fig. 81).

A unique face vessel that memorializes the life and accomplishments of famed abolitionist Frederick Douglass resides in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History (figs. 82, 83). Hand modeled and molded, the unglazed red earthenware pitcher was designed by John Edward Bruce (1856–1924) in Albany, New York, about 1896.[94] Born into slavery in Maryland, Bruce became a well-known American advocate of Black history and civil rights, had an illustrious journalistic career, and founded newspapers in Washington, Baltimore, and New York. While the actual maker of the pitcher is unknown, it was probably created for inclusion in the Tennessee Centennial Exposition held in Nashville in 1897; Bruce had been recruited by New York’s Governor Levi P. Morton to formulate an exhibition advocating New York’s Black history.

Face Vessels: A Southern Legacy

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, rural white potters working in the South and the Midwest added face vessels to their repertoire of traditional jugs and jars. While retaining the general features of the types produced by nineteenth-century African American potters, these examples became more personal aesthetic expressions, being whimsical, if not overtly comical. Joseph Gregory Baynham (1841–1906) is one such potter who worked in the Edgefield alkaline-glaze tradition near Trenton, South Carolina. He may have begun his operation as early as 1880, and by the 1890s the Baynham factory was producing tremendous volumes of utilitarian stoneware forms.[95] At ground zero for the earlier production of slave-made face vessels, the Baynham potters made several face vessel forms including jugs, banks, chicken feeders, and pitchers (fig. 84). An important example resides in the Colonial Williamsburg Collection, made and signed by Joseph Baynham’s eldest son, Mark (1878–1937) (fig. 85).[96] By age nineteen he was making his own pottery at his father’s Trenton works.[97] During excavations of the site, his stamp “MARK” was discovered on three whole jugs; another intact jug exists in a private collection.[98] The appearance of the Baynham face vessels is similar to that of the earlier African American Edgefield face vessels, and although kaolin highlights are not added, the teeth and eyes are highlighted by leaving them unglazed.

Another later South Carolina face jug maker was John Leonard Atkins, who worked on the Jug Factory Road, in Greenville County, South Carolina, circa 1900.[99] Like the Bayhnam factory, Atkins primarily produced utilitarian jugs, jars, crocks, and churns; he also made face vessels emulating the Edgefield style, but with a “glassy, black feldpsar glaze.”[100] Surviving examples of his face vessels are relatively rare, and all seem to have strap handles and sometime the addition of color highlights (fig. 86). Atkins did not use kaolin highlights like the slave-made Edgefield face jugs, instead he substituted broken bits of white porcelain plates to create the teeth and pupils. Consequently, Leonard’s face jugs should be considered an important transition since the use of porcelain fragments would be adopted by most Southern face jug makers, a technique that continues still.

Salt-glazed stoneware face vessels were made by Charles Frederick Decker (1832–1914) and his sons in their Keystone Pottery in eastern Tennessee during the late nineteenth century.[101] Decker, a German immigrant, had first trained in the Remmey pottery in Philadelphia, learning the style of salt-glazed stoneware and ultimately establishing his own works there in 1857. After several moves through Virginia, he arrived in Tennessee in 1872, where he and his sons established the Keystone Pottery, a thriving concern making utilitarian crocks, jugs, churns, and pitchers. The Deckers’ face vessels were very much in the Philadelphia “Remmey” style.[102]

An extraordinarily detailed example made by Charles’s brother William (b. 1859) in 1892 is illustrated in figure 87.[103] With considered modeling, textured eyebrows, sideburns, moustache and beard, and a hat, the jug is clearly intended to portray “L. W. Berry,” whose incised name is recorded on the back. Berry’s identity and relationship to the Decker family has yet to be determined. Other Decker face jug examples, although more stylized, also include beards and moustaches, perhaps referencing either the maker(s) or someone else from within the pottery.

In the twentieth century, Southern potting dynasties arose in Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina, including the production of face jugs.[104] The production of face vessels has been documented as far west as Kentucky, Mississippi, and Illinois.[105] While these jugs initially augmented the utilitarian wares typically produced in these regional potteries, over time they became sought-after decorative items, with some of the potters attaining celebrity status among folk art collectors (figs. 88–91). This was especially true for the potters of North Georgia, whose stories have been told best by folklorist John Burrison (b. 1942) in his many writings, exhibits, and lectures.[106] In 2006 the Folk Pottery Museum of Northeast Georgia (where Burrison serves as curator) opened; it maintains collections and presents interpretive exhibits on the face jug makers of North Georgia.[107]

Looking Ahead—Culture of the American Face Jug

The making of face vessels by America’s folk potters continues today and shows no signs of diminishing. As demonstrated in the many examples presented in this overview, many face vessels are expressions of both political and social issues. Contemporary potters are referencing social and political topics of the modern age and marketing their creations nationally via social media. Billy Ray Hussey (b. 1955) is one such potter, who was reared in Seagrove, North Carolina, immersed in the tradition of North Carolina pottery making.[108] Many of his creations are direct interpretations of the earlier nineteenth-century Edgefield styles (fig. 92); others are deeply personal creations reflecting Hussey’s views on political, social, and religious topics. North Carolina-based artist Jim McDowell (b. 1945) also specializes in highly sculpted stoneware face vessels (fig. 93). One of the few Black Americans making face vessels today, he has been called a “ceramics activist” because his work references issues of racism and social injustice in America.[109]

Other contemporary potters have been especially invested in replicating period Edgefield-type face jug examples to understand those period techniques and materials better. These include South Carolinians Michel Bayne (b. 1959) working in the Catawba Valley, Stephen Ferrell (b. 1945) of Edgefield, and Peter Lenzo (b. 1955), previously in Columbia, South Carolina (figs. 94–96).

From cave paintings to twenty-first-century social media, the rendering of the human face has been one of mankind’s more enduring artistic expressions. Today there are hundreds of face jug makers employing the latest technology, glazes, and fantastical images. A recent quick search on the eBay online auction site using the search term “face jug” returned over twelve hundred listings. The introduction of “artificial intelligence” has become part of the potter’s oeuvre for creating new face jug designs.[110] The capture of the human visage in clay will remain a vital and fascinating record of aesthetic, religious, historical, and social expression. Ceramic historians will continue to draw on that rich and diverse resource for documenting and interpreting this uniquely clay art for years to come.

Cinda K. Baldwin, Great & Noble Jar: Traditional Stoneware of South Carolina (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993); Jill Beute Koverman, Making Faces: Southern Face Vessels from 1840–1900 (Columbia: McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, 2001); John A. Burrison, Global Clay: Themes in World Ceramic Traditions (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017); Claudia Arzeno Mooney, April L. Hynes, and Mark M. Newell, “African-American Face Vessels: History and Ritual in 19th-Century Edgefield,” in Ceramics in America, edited by Robert Hunter, (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England for the Chipstone Foundation, 2013), pp. 2–37; and the Chipstone Foundation’s 2012 exhibition Face Jugs: Art and Ritual in 19th-Century South Carolina, curated by Claudia Mooney (see note 2 below).

In the last decade numerous nationally organized exhibitions of face vessels have taken place. In 2012 Face Jugs: Art and Ritual in 19th-Century South Carolina opened at the Milwaukee Art Museum and subsequently traveled to the Columbia (S.C.) Museum of Art, the Birmingham (Ala.) Museum of Art, and the Georgia Museum of Art (available online at http://chipstone.org/exhibitionframe.php/5/Face-Jugs/). Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina, an exhibition of Edgefield stoneware that included twenty-two face vessels, appeared at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, September 9, 2022–February 5, 2023. Expressions of Power: Face Vessels of Edgefield District, was presented at the Greenville County (S.C.) Art Museum, October 14, 2022–January 22, 2023.